Knowledge Requirements in the Governing Documents of the Swedish Police Programme

An Explorative Study of the Programme's First Semester

Associate Professor in pedagogy, Malmö University, Sweden

Corresponding author

Professor in pedagogy and work, Malmö University, Sweden

Publisert 14.03.2022, Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing 2022/1, side 1-16

Our study investigates how knowledge requirements are formulated in policy documents for a police education situated in an academic context. Through an explorative quantitative and qualitative content analysis, we seek to answer the following questions: What knowledge requirements are presented in course syllabi for the first semester of five different police programmes in Sweden? What similarities and differences are there? The result implies that a higher education policy frame dominates the design of curricula and program profiles. Lower-order cognitive skills are predominant in the knowledge requirements in the first semester of all police training programmes in Sweden, but with a balance of academic and professional practices, and of conceptual and contextual coherence in curricula. The universities differ mostly when it comes to knowledge requirements on a higher-order cognitive level, and here there is an imbalance in sequence and pace in curricula between different programmes. Both balance and variations are discussed with the aim of opening up for an innovative debate on knowledge requirements in police education.

Keywords

- Curricula

- knowledge requirements

- police education

- profession

1. Introduction of problems, knowledge gaps and aim

This study investigates how knowledge requirements are formulated in policy documents for a police education situated in an academic context. In Sweden, the police programme is offered as a contract education at five universities, with the Swedish Police Authority as the client. The national Programme Syllabus for the Police Programme (Swedish Police Authority, 2018) is the same for all five universities; however, the course syllabi for each semester are decided locally at each university. So, even though the Swedish police education is not yet a university education with a degree, when it comes to the curricula and local profiles, it is designed as one. Thus, the knowledge requirements stated in the national Programme Syllabus for the Police Programme (Swedish Police Authority, 2018) are transformed in different ways on the next policy level, i.e. within the higher education setting. It has been suggested that the police training should be converted into a higher education programme (SOU 2016:39), but no formal decision has been made since the proposal in 2016. Thus, the programme is designed as a bachelor’s programme, but without the formal status of a bachelor’s degree. Students can, however, apply for credits.

The police education comprises of five semesters, one being full-time in-service field training (Kohlström et al., 2017). The police education rests on three foundation pillars: (i) an interdisciplinary scientific starting point including subjects such as criminology, law, health sciences, behavioural sciences, social work and political science; (ii) a practical police approach focusing on the knowledge and skills needed to become a professional; (iii) an interdisciplinary and practical police approach as a whole where understanding the interdependence between theory and practice is central. The five police programmes have different profiles: Borås University has specialised in healthcare; Linnaeus University was the first in Sweden to build a research centre; Malmö University has gender studies as a profile; Södertörn University has chosen social work, and finally the police programme at Umeå University is focused on sports and health.

Not only do the five different profiles and specialities necessitate and make it interesting to investigate similarities and differences between the programmes and the course syllabi, but also the fact that the time span between the oldest established police education was as early as in 1970 and the two most recent ones as late as in 2019. In addition, the feeling of academic freedom, regulated in the Higher Education Act, is firm in Sweden. Academic freedom implies every university teacher’s right without restriction to choose what subject matter to teach and what teaching method to use. As a consequence, teaching in higher education, e.g. in the police education, can differ a great deal between universities and between police educators.

In many countries, the police education has long been organized and governed by academia. Two examples are the UK, with an academic degree in policing as early as in the 1960s, and Finland, with a reform introduced during 1998 (Lee & Punch, 2004; Myllylä et al., 2017). In other countries the transition has just begun (Cordner & Shain, 2011; Bartkowiak-Théron, 2019). In the Nordic countries, Norway has a police education at the bachelor level, while Denmark has a similar solution as Sweden – awaiting formal status (Fekjær & Petersson, 2018; Myllylä et al., 2017). In an international perspective, the Swedish example can be interesting for all interested in the ongoing academization of a professional police education and the development of knowledge.

As Swedish police education is standing at the threshold of higher education, there are several actors involved on a policy level. Due to the contract form, the programme Syllabus for the Police Programme is approved by the Swedish Police Authority as a steering document. However, the course syllabus is sanctioned independently at every police training centre, each of them situated at a university. The formulations of forms of knowledge found in different policy documents in higher education can be traced back to the Bologna Process and its quality assurance guidelines (Bergen communique, 2005). The universities and each individual police programme then develop intended learning outcomes (ILO), as in what the student is expected to know and be able to do after they have completed a course or programme. This means that the universities must ensure that the education programmes meet the requirements formulated in the systems of qualifications, but also that the institutions are free to choose how they achieve this.

The police profession has traditionally been characterised by a focus on experience and practice-based knowledge, but demands are growing for evidence-based knowledge. A more academically oriented training programme provides police officers with more opportunities to apply scientific perspectives in practice. The official report “The Police in the Future – A police higher education programme” (SOU 2016:39) refers to a police education programme with close links to research. We can observe a similar trend internationally as police training programmes have evolved towards integrating both scientific and practical knowledge (Jaschke, 2010).

So, what knowledge should a Swedish police student develop? The professional life of a police officer is characterised by changing requirements regarding the procedural knowledge expected of professionals in contemporary society. Creative and innovative skills are required in the application of knowledge. The procedural knowledge can be of a practical character, such as for administrative duties, but may also take the form of social skills, such as leadership and the ability to cooperate, and intellectual abilities, such as decision-making and problem-solving (Bäck, 2020; Ellström, 1992). A possible tension between different forms of knowledge as well as between adaption and development is not unique to police training. Similar tensions can be found among university teachers and in programmes for teachers and nurses (Heslop, 2012). When vocational education becomes more theoretical, there is a risk of increasing the gap between the education and the practical skills required in professional life (Lindberg, 2012). Another important question is employability and how police education prepares students for a career in policing (Pepper et al., 2017).

The complexity of the police profession is highlighted in the Programme Syllabus for the Police Programme (Swedish Police Authority, 2018). The syllabus states that professional knowledge and experience, as well as professionally relevant experiences, are a central aspect of the police programme. Police graduates must have the ability to: make independent and critical assessments, independently identify, formulate and solve problems, face changes to their profession; seek out and value knowledge on a scientific level, and also stay up to date on the development of knowledge. Since it is in the interest of our study to examine how the knowledge requirements are formulated in the policy documents, we believe that it is of particular interest to examine all the police programmes in Sweden and compare the first-semester course syllabi from the different universities. This focus is even more relevant since there is a lack of research with a focus on what type of knowledge is taught in police education (Hove & Vallès, 2020). Have five different profiles and a period of establishment pushed the police educations’ syllabi in different directions? If so, in what ways? How is the intention of safeguarding national unity in the same study programme syllabus for all police educations in Sweden guaranteed?

The aim of the study is to investigate how knowledge requirements are formulated in policy documents for a police education situated in an academic context. Our study focuses on the following two questions:

RQ 1. What knowledge requirements are presented in the different course syllabi in the first semester of the different police programmes?

RQ 2. What similarities and differences are there?

2. Previous research

Even if academic police educations have existed in several countries for years, there is still an ongoing debate of the value of higher education and conflicting research results on whether a police officer benefits from a university degree in terms of occupational career (Paoline et al., 2015). Others present evidence that higher education could add learning processes to the police training, processes that are scientifically substantiated with a focus on theoretical knowledge, communicative abilities and problem solving (Grosemans et al., 2017; Paterson, 2011). Another argument is that higher education helps police officers make decisions in a reflective manner, which could contribute to the development of the professional culture within the police force (Cox & Kirby, 2018). There is research to suggest that police candidates do not see themselves as “real” university students, nor do they question the academic perspective in their training (Heslop, 2011; Jaschke & Neidhardt, 2007). In Bäck’s dissertation (2020, p. 43), it is revealed that when active police officers look back at their training, they express that they would have liked to see fewer theoretical and more practical elements over the course of the police programme. On the other hand, Bäck also shows that practical skills are considered the least important by police candidates, both at the start and the end of their training (ibid., p. 39). Williams et al. (2019) and Bäck (2020) show that police officers with higher education are keen to use their acquired knowledge but experience varying opportunities to apply it to practical police work. In other words, there seems to be a contradiction between what is needed in terms of content and what is valued as important forms of knowledge (Handegård & Berg, 2020). There may also be a lack of understanding among active police officers, as they might struggle to accept new police officers with an academic education (Fleming & Wingrove, 2017). Swedish research on police training has focused on the transition between police training and the police profession (Bäck, 2020), and on police officers’ individual and collective experiences of being police educators (Bergman, 2016). According to Bäck (2020), police training programmes are in a constant state of change in an effort to adapt them not only to higher education but also to the changing demands on the police officer.

In summary, prior research shows that there are hopes as to what an academic police training programme could contribute, such as scientifically educated police officers who can help develop the profession. At the same time, it is not clear whether students or professionals see the same opportunities. There is also a lack of systematic reviews about how knowledge is formulated in policy documents, and how the educational assignment is presented with a focus on knowledge and learning aspects. This constitutes a knowledge gap, and there is a need to investigate the relationship between the police training on the one hand, and the police profession on the other, with regards to how knowledge requirements are formulated in the policy documents of the police training programmes.

3. Theoretical framing

To further understand how knowledge requirements are formulated and balanced in a professional police education situated in an academic context, the concepts conceptual and contextual coherence and curriculum could be helpful (Muller, 2009). Inspired by Bernstein’s (2000) hierarchical and horizontal knowledge structures, conceptual coherence can be understood as the core of the discipline with a hierarchy of knowledge – in relation to police education, this could be the more theoretical scientific knowledge grounded, for example, in police research or criminology. Contextual coherence is connected to an external context for legitimacy. In relation to the police education, this would be the knowledge requirements that the police profession imposes on a police training programme. Consequently, knowledge requirements in a police training programme recalls other vocational curricula with two directions – inwards to academic practice and outwards to professional practice:

We propose that to understand the logic of vocational knowledge practice is to grasp both of these directions: its capacity for increasing conceptual complexity and its capacity to engage with increasingly specialized problem-situations (Steyn, 2016, p. 4).

This way of understanding knowledge blurs the division of theoretical and practical knowledge and resonates more with the idea that there is always a mix of different conceptual and contextual coherence features between disciplines. Even within a discipline, the emphasis can vary (Muller, 2009).

In the case of police education, the ambition stated in the Programme Syllabus for the Police Programme (Swedish Police Authority, 2018) is to mix practice-oriented ‘know-how’, which is essential for professional tasks, with a disciplinary core, which is the ‘know-why’ grounded in subjects such as criminology. In our article, the conceptual and contextual curricula will be used to deeper understand how different knowledge requirements are balanced in the first semester curriculum of Swedish police education. This theoretical frame is combined with Lauvås and Handals’ well-established praxis triangle theory (2015), which is based on the idea of supporting the individual in relating valuations and theoretical knowledge into practice. The ability to develop independent reflection around conscious as well as unconscious knowledge, based on three elements – own experience, others’ experience, and one’s own values – is central to the exercise of a profession.

4. Materials and methods

Our study is an exploratory pilot project in which we investigate the institutional course syllabus and not how the knowledge requirements are interpreted, implemented and practically achieved. In order to answer our two research questions, we have opted to use explorative quantitative and qualitative content analysis methods (Bryman, 2002). The quantitative analysis focuses on the verbs used in the police programme syllabi for the first semester, with the SOLO taxonomy as an analytical framework (Biggs & Tang, 2011). Taxonomies are not neutral and general; rather, they are based on different perspectives on learning (Säfström, 2017). The SOLO taxonomy focuses on how the students are expected to act to demonstrate the knowledge they have acquired at the end of a course. However, in our article, the SOLO taxonomy is used as an analytical tool to illustrate how knowledge requirements are expressed in the form of verbs, and also how the verbs are distributed in each police training programme. We were inspired by Braband and Dahl (2009) and use their approach as a starting point for illustrating how higher learning institutions express their knowledge requirements and on what levels these requirements can be placed. In other words, the focus of the study is not how the learning student expresses knowledge, but rather the formulated requirement levels. The qualitative analysis was inspired by Braun and Clarke (2006), as a thematic approach to identifying common themes in the material. This process involved theme searching, theme review, defining themes, and naming themes. One author initially consolidated the material to identify themes, then the themes were discussed and revised between the two authors.

4.1. Selection

The first semester course syllabi from all police programmes in Sweden are included in the material. The oldest police training programme in Sweden can be found at Södertörn University (previously known as the Swedish National Police Academy, Solna, founded in 1970 and moved to Södertörn in 2015). The oldest contract education hosted at a university is the police training programme in Umeå, which was started in 2000, followed by Linnaeus University, which started in 2001. The programmes in Borås and Malmö are the latest additions, launched in the spring of 2019. The decision to limit the study to the first semester was made as at the time of writing the police training programmes at Malmö University and Borås University have yet to complete a full programme. The latest versions of each course syllabus were obtained from the website of each university.

4.2. Implementation

The starting point is the SOLO taxonomy levels: pre-structural (1), unistructural (2), multi-structural (3), relational (4) and extended abstract (5). All levels of learning are analysed and the verbs used have been placed in the taxonomy levels, as in the example below (Brabrand & Dahl, 2009).

Table 1. Examples of active verbs in different SOLO classifications based on Braband & Dahl (2009, figure 5, p 539).

| Quantitative | Qualitative | ||

| SOLO 2 | SOLO 3 | SOLO 4 | SOLO 5 |

| Unistructural | Multi-structural | Relational | Extended abstract |

| IdentifyCalculateReproduceArrangeDecideDefineRecognizeFindNoteSeekChooseTest programSketchPick | DescribeAccount forApply methodExecuteFormulateUse methodSolveConductProveClassifyCompleteCombineListProcessReportIllustrateExpressCharacterize | Apply theoryExplainAnalyseCompareArgueRelateImplementPlanSummarizeConstructDesignInterpretStructureConcludeSubstantiateExemplifyDeriveAdapt | DiscussAssessEvaluateInterpretReflectPerspectivePredictCriticizeJudgeReason |

Note that the active verb apply can be placed in both SOLO 3 and SOLO 4, depending on what is being referred to in the intended learning outcome. Braband & Dahl (2009) distinguish between apply method (SOLO 3) and apply theory (SOLO 4).

In order to increase interrater reliability, we examined each course syllabus individually and SOLO classified the verbs that were used. We then discussed the course syllabi and our classifications with Brabrand & Dahl (2009) as our guiding principle.

4.3 Methodological deficiencies

Through a quantification of verbs used in the first semester course syllabi using a SOLO analysis, we have investigated how knowledge requirements are formulated in policy documents for a police education situated in an academic context. The SOLO taxonomy’s contribution as an analytical tool has contributed to highlight how knowledge requirements are expressed in the form of verbs in the different first-semester course syllabi. However, the taxonomy provides a hierarchical breakdown of knowledge that does not capture the whole complexity of knowledge and skill requirements in a vocational education such as the police training programme. It also highlights the difficulties of forcing knowledge into an existing framework. This is why it is important to recall that a quantitative analysis only offers a limited survey on the institutional level and not on the implementation level. We can note where the police training programmes decide to place a knowledge requirement in the form of verbs, but we cannot make any assumptions, linked to the context in which these demands were created, why they were placed in a certain way, or how educators and students interpret them. The quantitative SOLO classification was therefore supplemented with a qualitative thematic analysis.

5. Results

Below, we list the verbs included in the first semester’s intended learning outcomes for all the police programmes in Sweden. The verbs are classified into SOLO levels by us. We also report the distribution as a percentage in order to compare the distribution across the universities. This is followed by representative examples of intended learning outcome formulations in the course syllabi, then we will present a comparison of the verb distribution in the course syllabi at the different universities. Finally, we present the results from the qualitative thematic analysis.

Table 2. SOLO classification of verbs for the first semester of the Swedish police programmes.

| Borås University | |||

| SOLO 2 | SOLO 3 | SOLO 4 | SOLO 5 |

| Unistructural | Multi-structural | Relational | Extended abstract |

| Understand (5)Write (2)Use (1)Classify (1)Show (1)s:a= 10 (16%) | Account for (11)Describe (5)Conduct (3)Differentiate (1)Apply method (1)Revise (1)Communicate (1)s:a= 23 (36%) | Analyse (4)Explain (3)Apply (3)Relate (2)Revise (1)Reason (1)s:a= 14 (22%) | Reflect (9)Evaluate (5)Criticize (1)Judge (1)s:a 16 (26%) |

| Linnaeus University | |||

| SOLO 2 | SOLO 3 | SOLO 4 | SOLO 5 |

| Unistructural | Multi-structural | Relational | Extended abstract |

| Identify (4)Use (2)Produce (2)Seek (1)Read (1)Record (1)Recognize (1)s:a 12 (23%) | Account for (11)Conduct (4)Apply method (3)Describe (1)Formulate (1)Classify (1)Present (1)Solve (1)Use method (1)Prevent (1)Secure (1)s:a 26 (49%) | Apply (3)Analyse (3)Explain (3)Reason (1)Relate (1)s:a 11 (21%) | Discuss (2)Interpret (1)Argue (1)s:a 4 (7%) |

| Malmö University | |||

| SOLO 2 | SOLO 3 | SOLO 4 | SOLO 5 |

| Unistructural | Multi-structural | Relational | Extended abstract |

| Identify (2) Seek (1) Complete (1) s:a= 4 (8 %) | Account for (15) Describe (1) Solve (1) Illustrate (1) Conduct (1) s:a= 19 (37%) | Explain (3)Apply (2) Analyse (2) Relate (2) Implement (1) Motivate (1) s:a= 11 (22%) | Discuss (7) Evaluate (1) Reflect (5) Reason (2) Criticize (1) Problematize (1) s:a= 17 (33%) |

| Södertörn University | |||

| SOLO 2 | SOLO 3 | SOLO 4 | SOLO 5 |

| Unistructural | Multi-structural | Relational | Extended abstract |

| Identify (1)Seek (1)Act (1)s:a= 3 (10 %) | Account for (9)Describe (3)Present (1)Apply method (1)s:a= 14 (46%) | Explain (3)Apply (3)Relate (1)s:a= 7 (22%) | Discuss (3)Evaluate (1)Judge (1)Reflect (2)s:a 7 (22%) |

| Umeå University | |||

| SOLO 2 | SOLO 3 | SOLO 4 | SOLO 5 |

| Unistructural | Multi-structural | Relational | Extended abstract |

| To know (5) Define (3)Identify (3) Divide (2) Find (1)Show (1) s:a=15 (26%) | Account for (7) Apply (2)Describe (5) Conduct (5)Execute (4)Understand (2)s:a=25 (43%) | Explain (10) Apply (5)Solve (1)s:a = 16 (28%) | Discuss (2) s:a = 2 (3%) |

The multi-structural level (SOLO 3) is the most common at all the universities. The predominance of SOLO 3 (36, 49, 37, 46 and 43 %) also means that all police programmes place most of their knowledge requirements on a multi-structural level, as in a focus on a number of different aspects on one subject that are not related to each other, nor analysed and discussed (Biggs & Tang, 2011). However, the examples from the universities show that SOLO 3 covers formulations for intended learning outcomes that Jaschke (2010) refers to as both scientific and practical knowledge. This means that the most commonly used verb in all the syllabi – account for – can be used to both “Give a general account for the sub-sections of civil law; Account for the basic principles of democracy and human rights from a national and international perspective; Account for the organisation and governance of Swedish public administration; Account for the regulations and general advice specified in the Swedish Police Authority security guidelines regarding information processing with the help of IT” as well as “Account for how individual stress affects the ability to act adequately.”

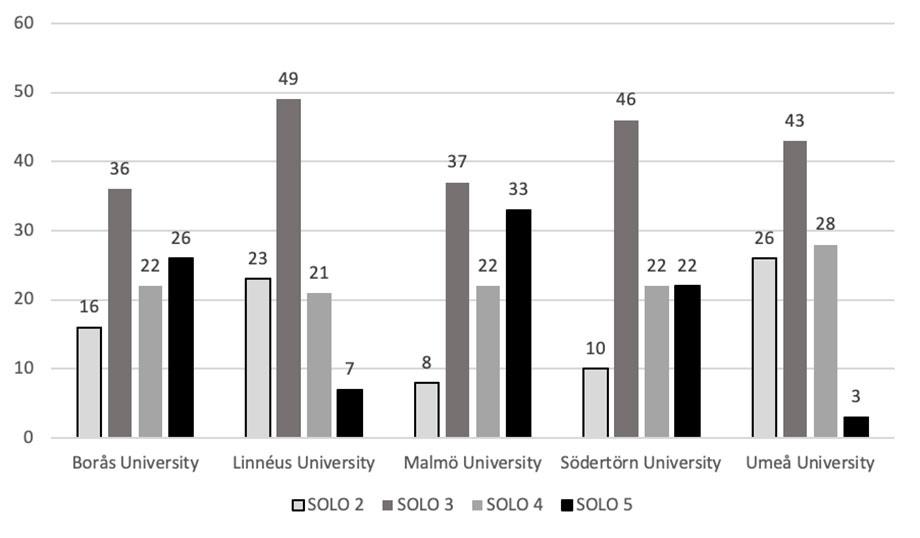

The extended abstract level (SOLO 5) is the level that sets the universities most apart. Malmö University tops the list with 33 % of its verbs being placed at the highest level, followed by Borås University and Södertörn University with 26% and 22% of their verbs in the SOLO 5 level respectively, while Linnaeus University and Umeå University have 7% and 3% of their verbs in the SOLO 5 level respectively. SOLO 5 entails requirements of being able to integrate several different aspects, to see complete pictures and make comparisons, and to draw conclusions, discuss and apply knowledge in other contexts (Biggs & Tang, 2011), which these examples clearly illustrate: reflect on how attitudes and values of one’s own can be affected by the future professional role; make reasonable judgement of what legal consequence may be appropriate for a certain crime.

The comparison shows that a police student studying at Malmö University, Borås University and Södertörn University will be faced with a considerably higher number of knowledge requirements with verbs of the highest level in the course syllabi during their first semester compared to a student at the police programme at Linnaeus University or Umeå University. When comparing the percentage distribution, the following pattern emerges:

Figure 1

Percentage distribution of verbs into SOLO levels at all police programmes.

The percentage comparison illustrates that the two recently launched police programmes in Malmö and Borås have the highest levels when applying the SOLO taxonomy regarding the verbs used to describe knowledge requirements in the first semester of the programme. This means that early on in their training, police students at one of these universities will be exposed to course syllabi where, according to the SOLO taxonomy level classification of verbs, the level of requirements is higher compared to, for example, Umeå University, which is at the bottom of the taxonomy and has existed within academia the longest (launched in 2000). The illustration also reveals that the police programme with the most even distribution of words, based on the levels of the SOLO taxonomy, can be found at Södertörn University, home of the oldest police training programme, even though it was moved to a university as late as 2015.

In summary: Our results accentuate great differences between police training universities in curricula design when it comes to using active verbs stimulating abstract thinking, and expose the dominance of verbs on a multi-structural level. The total number of verbs in the course syllabi for the first semester differs between the various Swedish police programmes. A police student attending Södertörn University, with the oldest police program, will be faced with 31 verbs during their first semester, while a student at Borås University, with the youngest police programme, will face 63 verbs. The course syllabi for all police programmes are dominated by knowledge requirements on SOLO level 3, i.e. a multi-structural level, during their first semester. There are similarities in how the universities use verbs placed in SOLO 3, and the verb Account for is the most frequently used, covering both scientific and practical knowledge. The universities differ primarily when it comes to knowledge requirements on SOLO level 5 – the extended abstract. This level is dominated by the two most recently launched programmes (Malmö and Borås), while the oldest programme situated within academia (Umeå) has the lowest percentage. The police programme with the most even distribution of verbs based on the SOLO taxonomy levels is Södertörn University. However, we can gain a deeper understanding of the formulation of knowledge requirements through a qualitative thematic analysis. In the following section we present themes that concern different aspects of balance and imbalance.

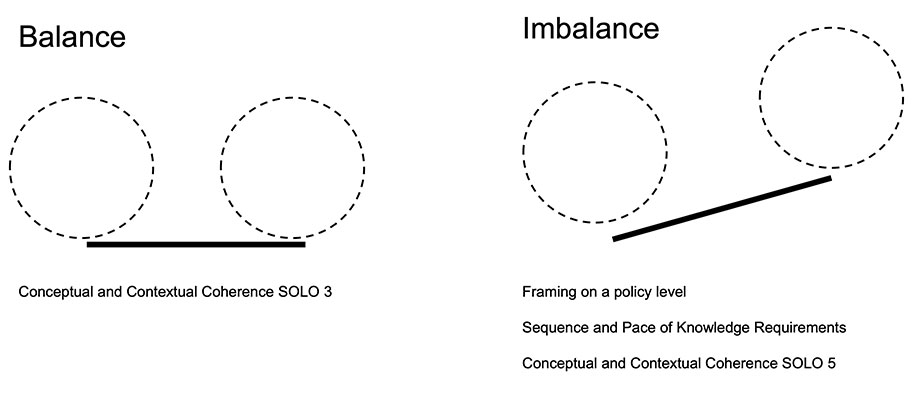

Figure 2. Illustration of balance and imbalance in the formulation of knowledge requirements.

5.1 Imbalance in framing on a policy level

Our results reveal a professional police education not only situated in higher education, but also outbalanced by higher education policy when it comes to curricula and local university profiles. The contract police education is applying the higher education way to formulate knowledge requirements, with goals and active verbs and a constructively aligned curricula. The higher education frame is also visible in the variation of learning goals. A police student can choose between five different police programmes in Sweden, with different ways to formulate knowledge requirements in their curricula, all in accordance with the policy in higher education. The variation is highlighted through the number of verbs, through the choice of different verbs, and through the different SOLO levels.

The Programme Syllabus (Swedish Police Authority, 2018) is a national document, and it adheres to the Higher Education Ordinance’s method for formulating intended learning outcomes. This means that all police programmes could basically have similar course syllabi, but the Swedish police programmes adhere to the framework of academia, i.e. the university’s freedom to ascribe a profile to the programmes. For an academic programme, it is not unusual for the universities to present their course syllabus and knowledge requirements differently. For example, in nurse training, medical education and teacher training, it is common for universities in Sweden to have local profiles. The Higher Education Ordinance (HF) (SFS 1993:100) specifies the requirements students must meet. In addition, universities write local programme syllabi that show how the programme in question covers the requirements set out in the Higher Education Ordinance. This is also a chance to give the programme a profile.

5.2 Balance in conceptual and contextual curricula – SOLO 3

In all the police programmes’ introductory course syllabi, we can find traces of knowledge requirements integrating both practical and theoretical knowledge. The multi-structural level, SOLO 3, based on the categorisation done by Biggs & Tangs (2011), concerns the active verbs in the course syllabi stating that several relevant details are to be reported in the answers, but the details do not need to be related to each other, and can also be an unstructured list. However, our material, based on the examples from SOLO 3 and the verb account for, shows that knowledge requirements on this level are formulated in a more complex way and focus on both practical skills and knowledge of a more abstract character. In this aspect, the universities’ method for presenting knowledge requirements is in line with the need for the integration and practical and theoretical knowledge as described in the Programme Syllabus (Swedish Police Authority, 2018) for the Swedish police training programmes, and as a prerequisite for the police profession (Fleming & Rhodes, 2018). This integration also resonates with the understanding of a typical vocational curriculum with a balanced mix of academic and professional practices, and a balanced mix of conceptual and contextual coherence (Muller, 2009; Steyn, 2016).

5.3 Imbalance in sequence and pace of knowledge requirements

However, a strong focus on the integration of different types of knowledge can result in a weaker focus on conceptual coherence or progression (Chisholm et al, 2000). We have detected an imbalance between the different police programmes when it comes to sequencing the knowledge requirements during the first semester. In the percentage comparison, the two recently launched police programmes in Malmö and Borås have the highest SOLO levels in verbs. All police training programmes contain what Biggs and Tang (2011) refer to as the qualitative shift towards the higher levels of the SOLO taxonomy (levels 4 and 5), where knowledge is to be placed and applied in a new context. These are requirements that are also presented in Programme Syllabus (Swedish Police Authority, 2018). However, when it comes to the first semester, we were only able to find traces of the shift between SOLO 2 – SOLO 5, these being given a great deal of space in the police programmes at Borås, Malmö and Södertörn. The results signal a variation in sequence and pace between the programmes and a need to be observant of how a curriculum maintains a congruence with both professional and scientific disciplines (Muller, 2009). These are results that require additional research and a move from the policy document level to an implementation level in the form of, for example, participatory studies and interviews with police students and police educators.

5.4 Imbalance in conceptual and contextual curricula – SOLO 5

A large number of intended learning outcomes on the extended abstract level of the SOLO taxonomy (SOLO 5) with knowledge requirements such as being able to discuss, evaluate, and reflect early in the first semester could cause the education to be perceived as theoretically abstract. When a police program, as in the example of Borås, Malmö and Södertörn, introduces knowledge requirements like this early on in the education, it might reflect an idea of the complexity of professional knowledge as something that cannot be learned in a linear, hierarchical process. The local programme variation and examples of high number of verbs in SOLO level 5 early on in some programmes signals an innovative and non-hierarchical way of thinking about knowledge requirements. Knowledge requirements on this level could also be a result of curricula design with the ambition to connect personal experience with both practical and theoretical knowledge. To be able to discuss, evaluate and criticise, one needs to build on personal experience as well as practical and theoretical knowledge (Lauvås & Handal, 2015).

In contrast, a low number of verbs on SOLO 5 could mean that the police students do not practice using their acquired knowledge with a critical approach early enough. It may be relevant to ask whether the police students are experienced enough at the very start of their education, or are ready to perform these qualified and abstract tasks. There could be a risk that the professional knowledge is outbalanced by the training of generic academic skills. Herein lies the challenge of creating a curriculum that is both conceptually and contextually coherent (Muller, 2009), but also variated and flexible enough to meet the changing knowledge requirements in policing.

6. Discussion of findings and implications

What then are the concrete implications of our study in connection to the various knowledge requirements? Returning to the research questions of our study, we discuss similarities and differences and two findings that are worth emphasizing: a critical approach and the value of variation.

The similarities are illustrated by the balanced mix of conceptual and contextual coherence in the knowledge requirements when it comes to the SOLO 3 level. There is also a similarity in imbalance when it comes to the dominant higher education frame on a policy level, for all police programs. The similarities on the SOLO 3 level, with knowledge such as being able to account for, describe and present, can be interpreted as a consensus among the five different police programmes of the enduring competencies and practical skills that are sometimes referred to as highly valued, real police work (Kohlström et al., 2017). In the police education there is an appreciation of developing and mastering facts and practical know-how in combination with more theoretical know-how in order to become a competent police officer.

The differences are highlighted by the imbalance between the different programmes in sequence and pace of how knowledge requirements are presented during the first semester, and finally, in how three programmes have a large number of verbs on the SOLO 5 level, thereby risking that professional knowledge is outbalanced by the training of traditional academic and generic skills. The difference on the SOLO 5 level, with verbs such as being able to discuss, evaluate and reflect, together with the imbalance in sequence and pace, can be interpreted as disagreement within the programmes on the so-called new competencies (Kohlström et al., 2017) comparable to academic and generic competencies. We understand this disagreement as ongoing work from the actors in the different police programmes on when the scientific knowledge on the extended abstract level should be introduced.

An important implication of our study is that educational organizers such as university teachers and administrators need to engage in critical discussion around the consequences of how knowledge requirements in learning goals are formulated in course syllabi and when they are introduced during a programme. University teachers and course administrators need to make explicit and motivate police students with regard to why different competencies are needed at different stages during the programme. For example, police educators need to be aware of the vast predominance of active verbs on the multi-structural level (SOLO 3) at the early stages of a university programme and the imbalance between the different programmes in sequence and pace of active verbs on the extended abstract level (SOLO 5).

According to Kohlström et al. (2017), students in early career stages have difficulties in differentiating competencies, and thus perceive both new and enduring competencies as important to learn. Consequently, since students have problems in understanding and prioritizing which competencies are key at different stages in the police education, police educators and course administrators need to take responsibility for this process. Local syllabi variations may not be a problem as long as the need for competencies and timing are well anchored, explained and understood by the students.

Teachers and education trainers are given the important task of taking a critical approach to the manner in which knowledge requirements are formulated in the course syllabi. Both the choice and interpretations of verbs influence the choice of content, teaching methods and examinations (Brabrand & Dahl, 2009). Curricula also direct how police educators and students perceive the training programme, and even if this particular study is conducted within a Swedish context, we argue that the results could be of use in an international police education context.

In the delicate act of balance between different interests, the praxis triangle theory (Lauvås and Handal, 2015) can support actors such as police educators and students in the effort of making police training a place for collaboration between practice and theory based on personal experience, others’ experience and one’s own values.

Another important implication is that variations in syllabi should be protected to create a dynamic police training programme where both the police profession and academia are given room to manoeuvre, and also the opportunity to influence the knowledge requirements. The interplay and tension between academia and different professions, or the room to manoeuvre, is by no means limited to the police profession or the Swedish context – on the contrary, this tension is acknowledged in professions in most countries.

However, programme profiles are not commonplace in an international context, and many countries have moved the other way. In Norway the curricula have been revised towards a more meaningful whole and a balance between research-based and practice-based knowledge in order to strengthen the professional profile (Hove, 2012). In England and Wales, there is a development towards a standardisation of the policy documents for police training in the form of the Police Education Qualification Framework (PEQF). Williams et al. (2019) argue that even if a framework has been developed in collaboration with academic institutions, these institutions are still responsible for the practical interpretation and implementation of the PEQF. Otherwise, standardisation risks limiting what is considered valid police knowledge (Williams et al., 2019).

7. Conclusion

Our study investigates how knowledge requirements are formulated in policy documents for a police education situated in an academic context. One conclusion is that variation and imbalance in knowledge requirements can be a good thing, opening up for a vivid discussion between students and educators not so much about what knowledge a Swedish police student should develop, but when. What type of knowledge is important at the beginning of a police programme and what type of knowledge is more important at the end? Furthermore, the discussion could also focus on how practice-based knowledge and evidence-based knowledge are integrated and why. Another conclusion is that there is a need to make the knowledge requirements well anchored with and well understood by the students in order to make the syllabi an active part of the police students’ learning process.

In the research presented in this article, we have deliberately chosen a limited perspective in scrutinizing the syllabi of the first semester of police education. The results merely reflect what is found in writing and are limited to the formulations in course syllabi. However, what actually takes place in the practical teaching and learning situation is still unknown. Consequently, a relevant next step in future research is to study how the knowledge requirements are recontextualised into practice, for example by studying how police educators and students perceive and interpret the intended learning outcomes. What happens in the recontextualisation of the knowledge requirements in the pedagogical practice?

References

-

Bartkowiak-Théron, I.(2019). Research in police education: current trends.

Police Practice and Research

, 20(3), 220-224. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2019.1598064 -

Bergen communiqué. (2005).

The European Higher Education Area – Achieving the Goals

. Communiqué of the Conference of European Ministers Responsible for Higher Education, Bergen, 19-20 May 2005. -

Bergman, B.(2016).

Poliser som utbildar poliser: Reflexivitet, meningsskapande och professionell utveckling

(Doctoral dissertation).Umeå universitet

. -

Bernstein, B.(2000).

Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity

. 2nd ed.Rowman & Littlefield

. -

Biggs, J&Tang, C.(1999/2011).

Teaching for Quality Learning at University

.McGraw-Hill

.The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press

. -

Brabrand, C.&Dahl, B.(2009). Using the SOLO taxonomy to analyze competence progression of university science curricula.

Higher Education

, 58(4), 531-549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9210-4 -

Braun, V.&Clarke, V.(2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology.

Qualitative research in psychology

, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa -

Bryman, A.(2002).

Samhällsvetenskapliga metoder

.Liber Ekonomi

. -

Bäck, T.(2020).

Från polisutbildning till polispraktik – polisstudenters och polisers värderingar av yrkesrelaterade kompetenser

. (Doctoral dissertation).Umeå universitet

. -

Chisholm, L.,Volmink, J.,Ndhlovu, T.,Potenza, E.,Mahomed, H.,Muller, J.,Lubisi, C.,Vinjevold, P.,Ngozi, L.,Malan, B.&Mphahlele, L.(2000).

A South African curriculum for the twenty first century

.Pretoria

:Department of Education

. -

Cordner G.&Shain, C.(2011). The changing landscape of police education and training.

Police Practice and Research

, 12(4), 281-285. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2011.587673 -

Cox, C.&Kirby, S.(2018). Can higher education reduce the negative consequences of police occupational culture amongst new recruits?

Policing: An International Journal

, 41(5), 550-562. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-10-2016-0154 -

Ellström, P.(1992).

Kompetens, utbildning och lärande i arbetslivet: Problem, begrepp och teoretiska perspektiv

.Publica

. -

Fekjær, S. B.&Petersson, O.(2018). Producing legalists or Dirty Harrys? Police education and field training.

Policing and Society

, 29(8). https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2018.1467417 -

Fleming, J.&Wingrove, J.(2017). ‘We Would If We Could … but Not Sure If We Can’: Implementing evidence- based practice: The evidence-based practice Agenda in the UK.

Policing

, 11(2), 202–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pax006 -

Fleming, J.&Rhodes, R.(2018). Can experience be evidence? Craft knowledge and evidence-based policing.

Policy and Politics

, 46(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557317X14957211514333 -

Grosemans, I.,Coertjens, L.&Kyndt, E.(2017). Exploring learning and fit in the transition from higher education to the labour market: A systematic review.

Educational Research Review

, 21, 67-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.03.001 -

Handegård, T. L., &Berg, C. R.(2020). Kunnskapsbasert politiarbeid–kunnskap til å stole på?

Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing

, 7(1), 39-60. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2703-7045-2020-01-04 -

Heslop, R.(2011). Reproducing police culture in a British university: findings from an exploratory case study of police foundation degrees,

Police Practice and Research

, 12(4), 298-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2011.563966 -

Heslop, R.(2012) I:Bergman, B.(2016).

Poliser som utbildar poliser: Reflexivitet, meningsskapande och professionell utveckling

(Doctoral dissertation).Umeå universitet

. -

Hove, K.(2012).

Politiutdanning i Norge: Fra konstabelkurs til bachelorutdanning (Police Education in Norway)

.Politihøgskolen

-

Hove, K.&Vallès, L.(2020). Police education in seven European countries in the framework of their police systems. InT. Bjørgo&M.-L. Damen.

The Making of a Police Officer: Comparative Perspectives on Police Education and Recruitment

.Routledge

. -

Högskolan i Borås (2019).

Kursplaner för polisprogrammets första termin

. Retrieved from: https://www.hb.se/Student/Mina-studier/Kurs-och-programtorget/Programtorget/Antagen-VT-2019/Polisprogrammet/ -

Jaschke, H. G.(2010). Knowledge-led policing and security: Developments in police universities and colleges in the EU.

Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice

, 4(3), 302-309. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paq012 -

Jaschke, H.-G.&Neidhardt, K.(2007). A modern police science as an integrated academic discipline: a contribution to the debate on its fundamentals.

Policing & Society

, 17(4), 303-320. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439460701717882 -

Kohlström, K.,Rantatalo, O.,Karp, S., &Padyab, M.(2017). Policy ideals for a reformed education: How police students value new and enduring content in a time of change.

Journal of Workplace Learning

, 29 (7/8), 524-536. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-09-2016-0082 -

Lauvås, P.&Handal, G.(2015).

Handledning och praktisk yrkesteori

(3.,[rev.] uppl.).Lund

:Studentlitteratur

. -

Lee, M., &Punch, M.(2004). Policing by degrees: Police officers’ experience of university education.

Policing and Society

, 14(3), 233-249. https://doi.org/10.1080/1043946042000241820 -

Lindberg, O.(2012).

Let me through, I’m a doctor: Professional socialization in the transition from education to work

. (Doctoral dissertation).Umeå universitet

. -

Linnéuniversitetet (2019).

Kursplaner för polisprogrammets första termin

. https://lnu.se/program/polisprogrammet/vaxjo-vt/ -

Malmö universitet (2019).

Kursplaner för polisprogrammets första termin

. https://edu.mah.se/polis -

Muller, J.(2009). Forms of knowledge and curriculum coherence.

Journal of Education and work

, 22(3), 205-226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080902957905 -

Myllylä, M.,Hakala, J. T., &Myllylä, M.(2017). Modernizing the police with research, development and innovation activities.

Nordisk politiforskning

, 4(01), 45-67. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1894-8693-2017-01-05 -

Paoline III, E. A.,Terrill, W., &Rossler, M. T.(2015). Higher education, college degree major, and police occupational attitudes.

Journal of criminal justice education

, 26(1), 49-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511253.2014.923010 -

Paterson, C.(2011). Adding value? A review of the international literature on the role of higher education in police training and education.

Police Practice and Research

, 12(4), 286-297. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2011.563969 -

Pepper, I. K.,Williams, P.,Green, T.&Ruddell, R.(2017). Developing employability for policing: An international undergraduate comparison.

The Police Journal

, 90(3), 246-260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X16677768 -

Swedish Police Authority. (2018).

Utbildningsplan för polisprogrammet

. (Dnr A070.568/2018). -

SFS 1993:100.

Högskoleförordningen

. -

SOU 2016:39

Polis i framtiden – polisutbildningen som högskoleutbildning

.Justitiedepartementet

. -

Steyn, D.(2016).

Enabling knowledge progression in vocational curricula: Design as a case study

.Routledge

. -

Säfström, A-I.(2017). Progression i högre utbildning.

Högre utbildning

7, 56–75. https://doi.org/10.23865/hu.v7.955 -

Södertörns högskola (2019).

Kursplaner för polisprogrammets första termin

. Retrieved from: https://dubhe.suni.se/apps/planer/new/showSyll.asp?cCode=1044PA&cID=5433&lang=swe -

Umeå universitet (2019).

Kursplaner för polisprogrammets första termin

. Retrieved from: https://www.umu.se/enheten-for-polisutbildning/utbildning/grundutbildning/ -

Williams, E.,Norman, J., &Rowe, M.(2019). The police education qualification framework: a professional agenda or building professionals.

Police Practice and Research

, 20(3), 259-272. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2019.1598070