Citizensʼ Views on the Importance of Different Areas of Police Work

A Best–Worst Scaling Approach

PhD student

Department of Police Work, Malmö UniversityCorresponding author

Associate professor

Department of Police Work, Malmö Universitycaroline.mellgren@mau.sePublisert 02.09.2024, Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing 2024/1, side 1-19

This study investigates public perceptions regarding the prioritization of different areas of police work in Sweden amid growing concerns over crime and public safety. Utilizing a best–worst scaling (BWS) approach, the research aims to discern which police activities citizens deem most and least important, thereby shedding light on public expectations for police resource allocation. The findings reveal a strong public emphasis on the importance of responding to emergency calls and addressing gang criminality. Conversely, administrative tasks and traffic safety are viewed as lower priorities. The article offers insights into the alignment (or misalignment) between public expectations and police practices, emphasizing the role of public opinion in shaping police strategies and the importance of balancing crime fighting with social service functions to maintain public trust and legitimacy in law enforcement.

Keywords

- Police

- priorities

- resource allocation

- policing

1. Introduction

Crime policy and the role of the police has gained increased attention in the political discourse, a trend that seems to be shared by the public. According to a recent study conducted by Andersson et al. (2021) and surveys conducted by different newspapers such as Lundborg Andersson (2018) as well as Roos and Israelsson (2018), crime policy issues have emerged as the top concern among voters in the latest election. This represents a significant shift from 2007, when crime policy was ranked at the bottom of the list (Demker & Duus-Otterström, 2007), suggesting a noteworthy change in public opinion and political priorities regarding crime policy issues. According to the latest SOM survey, an annual survey conducted by the SOM Institute at Gothenburg University, crime is now, for the second year, ranked as the publicʼs main area of concern, with organized crime being a significant issue, right after the situation in Ukraine (Andersson et al., 2023). Presumably, this concern is amplified by the increased media attention that crime, especially organized crime, has gained in recent years. The mediaʼs almost daily news reports on organized crime, open drug scenes, and gang shootings have contributed to a heightened sense of urgency and fear among the public. This phenomenon can be understood through the lens of “moral panic,” a sociological concept describing the process by which media and public discourse exaggerate a problem, leading to widespread public concern that may be disproportionate to the actual threat (Cohen, 2011). Moral panic involves a cycle whereby the media amplifies an issue, leading to heightened anxiety among the public and, subsequently, demands for swift government action. Additionally, an agency report showing that Sweden now has the highest rate of gun-related fatalities per capita in Europe (Brå, 2021) has likely fueled this phenomenon.

However, the police have received media coverage not only related to violence but also when facing criticism. Examples include extended passport processing waits after the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions, low clearance rates on numerous types of crimes, as well as their preparedness for police presence during demonstrations where Korans were burned, leading to riots on several occasions. The police have also been criticized by the national audit office (Riksrevisionen, 2023) for decreasing clearance rates of so-called everyday crimes such as burglary, damage to property, theft and traffic offenses. The situation is worsened by the fact that the police are forced to prioritize more serious crimes or have had to reallocate police officers to other areas or departments. The criticism from the national audit office has also been echoed by police officers concerned by the police prioritizing gang-related violence over other crimes (Asplund, 2023). A recent poll ordered by Swedish television reveals that the public has low confidence in the policeʼs ability to deal with organized crime (Leijman, 2023). Public dissatisfaction with police performance can negatively impact trust in law enforcement, underscoring the importance of strong relationships between the police and the public. The value of a solid police–citizen relationship extends beyond democratic ideals; it is widely believed to have a significant impact on the efficacy of law enforcement, affecting the willingness of the public to report crimes, provide crucial information, and adhere to instructions given by the police (see e.g., International Association of Chiefs of Police, 2018). Naturally, mechanisms for establishing strong police–public relations are crucial and have gained a good deal of academic attention. Transparency, impartiality, and fairness in interactions with citizens—commonly understood through the lens of procedural justice—is widely recognized for its role in establishing the legitimacy of law enforcement in the eyes of public (Tyler, 2006). However, this approach focuses on the processes of law enforcement. It is also worth considering that the content of police actions—what police do, not just how they do it—may play a significant role in building strong connections between police and the public.

If we acknowledge that the priorities underlying police actions can have significant effects, it would be valuable to examine some mechanisms that determine these priorities. The police may be understood as a street-level bureaucracy in that they provide a distinctive social service while interacting directly with citizens and making legal decisions that have a great impact on an individualʼs life (Liljegren et al., 2021). A distinguishing feature of such organizations is that the demand for public goods has no theoretical upper limit (Lipsky, 1980). The time spent fostering strong relations with citizens could always increase, the clearance rate on different types of crimes could be higher, the processing time could always be shorter, more crimes of different types could theoretically be prevented, and service functions could be more accessible. In short, the combination of not having a set upper limit while the available resources are limited means that some sort of prioritization is required. Prioritization is multifaceted and complex as it can occur on multiple levels. Politically, the police is governed through regulations issued by the Department of Justice. Organizationally, resources are allocated to different units of the police. Additionally, at the individual level, the judgments and actions of crime investigators and police officers on the streets also contribute to shaping priorities (Finstad et al., 2023). Prioritization, regardless of the level of decision-making, essentially involves the distribution of resources, including skills, staff, and time. While resource allocation is inherently strategic, the distinctive role of the police also relates these issues to legitimacy. This does not suggest that the police should uncritically follow public opinion. Police activities are legally regulated, and laws cannot be disregarded based on popular demand. Much of the policeʼs work is reactive and most crimes fall under general prosecution, which mandates the police to report and investigate them. Furthermore, it is important to note that there is not necessarily a single, unified public opinion on various aspects of police work. Opinions can vary among different subgroups in society, potentially leading to the neglect of minority viewpoints. Additionally, the police can play a crucial role in protecting minorities, such as in cases involving hate crimes, which are designed specifically with the intention to protect groups that are not in the majority. It is therefore important to note that public opinion should not directly guide police activities in a linear way. However, this does not undermine the value of public opinion entirely. By considering public opinion as one of many factors, rather than a definitive directive, understanding public opinions can contribute to a broader discussion about the potentially conflicting values in the policeʼs missions.

Naturally, dealing with the most serious criminality and protecting citizens is one of the policeʼs main tasks. According to the second paragraph of the Police Act the police should prevent, detect, and investigate crimes, maintain public order and safety, but also offer social services to citizens that do not necessarily require an authorized officer or a certain legislative mandate to perform. While often discussed in times of fiscal austerity, the concern is of principal interest, as priorities express the values of the police to the public while also providing a frame for democratic accountability (Higgins, 2019). “Traditional policing” represents one perspective on the role of the police, as illustrated by the views of the former British Home Secretary Theresa May in 2011: “We need them to be the tough, no-nonsense crime-fighters they signed up to become” (Millie, 2014). In reality, the scope of police activity is far more nuanced and multifaceted than that, often involving activities aimed at dealing with problems that are not necessarily serious or even crime-related (Boulton et al., 2017; Ratcliffe, 2021). The sociology of policing has shown that what the police symbolize is as—if not more—important than what they actually do (Loader, 2014). The police, in this view, matter because of their capacity to send signals that sustain (or undermine) peopleʼs sense of the social world as an ordered place and their feelings of belonging securely within it. Consequently, this broad perspective on policing goes beyond mere “crime fighting” to include a wide range of order and social service functions, leading to the common characterization of the police as a “secret social service” (van Dijk et al., 2015). In contrast to traditional policing, community policing (see e.g., Goldstein, 1990) is a strategy that focuses on building ties and working closely with community members. The core idea is to establish trust and cooperation, which can help to identify and solve problems collaboratively. As such, it is an approach to public safety that involves partnerships between the police force and the community. Community policing encourages officers to adopt a problem-solving mindset that goes beyond traditional crime fighting and understand the underlying issues contributing to crime and disorder. By engaging with community members, police can gain a more intimate knowledge of the neighborhood dynamics, which can aid in crime prevention efforts. Officers may work to improve social conditions by participating in community meetings, developing community contacts, and implementing community-based programs. This policing model acknowledges that police cannot solve public safety problems alone and must collaborate with the community to achieve lasting solutions, enhance quality of life, and improve trust in the police. In times of a rapidly increasing police force, the dynamic between different theoretical models for policing prompts a discussion about the essence of the police role.

If we consider the Swedish policeʼs strategic plan for 2020–2024, which guides the current and future prioritization of main tasks (Polismyndigheten, 2023), all tasks are listed as important, and the police is set to increase its ability and competence within most areas—although some areas are especially highlighted and can be interpreted as given higher priority than others. Violence against children and women, as well as organized crime, are identified as important areas that may have especially harmful consequences for society, and their prevention and investigation should be prioritized. These areas are also a priority for the government, and special national plans to combat violence against women and organized crime have been issued (Polismyndigheten, 2023). Terrorism and extremism are also highlighted as important threats to democracy that should be given priority.

Given the policeʼs role as both a symbol of authority with a unique right to use force and as a “secret social service,” it is valuable to consider the publicʼs views on the role of the police. Against this background we set out to examine the publicʼs prioritization of various police activities. Results from a citizen survey on prioritization are presented with the aim of contributing to the broader discourse on police remit and effective resource allocation within law enforcement. Swedish research in this area is limited, and even though annual polls on public trust in the police provide an important perspective, we currently lack studies that investigate views on prioritization between the different activities.

1.1 Public Views on Police Priorities

Seemingly, there is a general agreement in the public discourse that law enforcement agencies need additional resources, influenced by both the reality of the crime situation and, possibly, by the moral panic amplified by media coverage. The general budget of the Swedish police has expanded rapidly in recent years to address these concerns. To specifically tackle recent crime trends related to gang violence, the Police Authority received increased funding of SEK 500 million by 2021, alongside an overall aim for the Police Authority to increase by 10,000 new employees by 2024 (socialdemokraterna.se, 2017). However, the infusion of additional resources into the police force raises critical questions about how these resources should be allocated and used efficiently. By extension, the way the police prioritize can be considered an expression of what matters in policing and what the role of the police is.

Increased resources provide an opportunity to consider how to achieve the most significant effects by targeting personnel and interventions at the most important problems, meaning that prioritization is a possible mechanism for effectiveness. Naturally, a related issue is defining which problems have the greatest importance and thus deserve prioritization. In an academic context, particularly within the discourse of the evidence-based policing (EBP) movement, much attention has been given to “what works” in policing. However, the significance of whether something “works” is dependent on how important it is perceived to be. Hence, the question of what works should be supplemented by the consideration of what matters (Punch, 2015). In times of a growing police force and increased interest in crime policy issues, the question of what matters the most (and least) within the multicolored palette of police work is an increasingly relevant issue. Fundamentally, the question is what the remit of the police should be. While prioritization primarily possesses strategic implications, it also encompasses a normative dimension, within which public opinion is one important facet.

While the perspective of the police as merely crime-fighters may be too narrow, the alternative of applying a wide view of the responsibilities of the police runs the risk of becoming too broadly defined, thereby losing utility, as other actors could potentially do the same job more effectively (Millie, 2014). Although there is no straightforward answer as to where the position of the police remit should be on the continuum of narrow to wide, effective policing requires conscious decision-making informed by the potential pros and cons of different approaches. The question then is: What type of information should be considered? In a community-oriented approach to policing, it is important to consider the viewpoint of the public, as opposed to adhering solely to the perspective of the police (Webb & Katz, 1997). As such, indicators of how citizens view and assign value to specific police activities could function as a foundation for prioritization.

Numerous studies as well as agency reports have addressed the topic of citizensʼ views on the importance of different aspects of police work. Skogan (1996) reviewed numerous national surveys in the UK and concluded that the most important concerns to the public were sexual assault and burglary, while littering and parking offenses were of low priority. Interestingly, there was no direct link between perceived frequency of a problem and importance attributed to dealing with it. Beck et al. (1999) examined how citizens and police officers in Australia perceive the relative importance of various social and crime-related issues and concluded that activities associated with a traditional police role, such as collecting evidence and information on criminals, interrogating suspects, and responding to emergency calls, were deemed to be the most important among the citizens. In contrast, social or order-related problems, such as escorting vehicles and handling lost property, were found to be the least important. The mean values of public and police responses were highly correlated, indicating that, by and large, citizens and police officers agreed with one another. Similarly, Liederbach et al. (2008) examined public and police views in Texas, USA. They found dealing with youth gangs, violent crimes, and drug use at the top of citizensʼ list of priorities, indicating that enforcement-related responsibilities were perceived as most important; on the opposite end of the scale they found dealing with illegal parking, noise, and problems with neighbors. Although the public and police generally agreed on the order of the ranking of different duties, some differences were found as citizens valued order-keeping measures higher than the police did.

Salmi et al. (2005) investigated 4257 Finnish citizensʼ assessments of their wished-for and actual police activities, and the discrepancies between the two. Similar to numerous other reports, detecting suspects and criminals was considered most important, while dealing with crowds, invisible surveillance (CCTV, etc.), and traffic control were the least important. Interestingly, controlling drunk driving and public order in public places were also considered crucial for the police, a finding that has not been commonly found in other studies. In a fourth study conducted in Nebraska, USA, Webb & Katz (1997) used a randomized sample to investigate the value distribution attributed to various police activities. The mean value attributed was highest among activities that were closer to what is described as the “core mission” of the police, such as investigating gang-related activities and performing regular drug sweeps. In the middle of the scale, maintaining traffic safety, meeting with neighborhood watch groups, and other order-keeping activities were found, while social service-like activities, such as keeping the physical environment clean or meeting regularly with business owners, were at the bottom of the scale. This ranking was consistent across the population, both in the sense that people belonging to different social groups responded similarly, but also in a statistical sense, as the standard deviation from the means for different police activities was low.

Although the findings are rather consistent across different contexts, the results from questionnaire studies should be interpreted with caution, as measuring individualsʼ preferred priorities regarding police activities presents two significant challenges. First, the vast scope of police activities makes it difficult to encompass all aspects within a single survey, thereby limiting the range of alternatives and potentially influencing survey results. Second, as crime levels fluctuate and new crimes emerge, while others become less prevalent or receive less media coverage, individualsʼ attitudes and perceptions toward policing priorities may undergo rapid changes. Therefore, a key area of concern pertains to the underlying reason that shape individualsʼ preference for policing priorities. In an agency report, the British Police Foundation (Higgins, 2019) investigated not only the preferences of citizens but also the reasoning and underlying principles leading to a certain priority. In summary, they found that citizens were found to be willing to take on the role as a policy maker rather than the one of a “consumer,” thereby considering what ought to be prioritized when considering importance for society rather than personal interests, as well as the complexities that are associated with making trade-offs when dealing with different social problems. Two main properties were found to determine the assessed importance of a particular duty: impact, meaning the estimated harm caused to the victim, and remit, which is perceived responsibility in relation to other agencies or actors. Broadly speaking, this finding appears to align well with existing studies, as activities that can be assumed to possess these qualities are also commonly regarded as highly regarded priorities. In conclusion, there is a discernible trend in citizensʼ responses, assigning comparatively lower values to the social functions of the police force, high importance to crime-fighting functions, while order-keeping functions are typically found in the middle-range category.

1.2 The Present Study

The present study has two primary aims: the first is to identify overall patterns in citizen ratings of the importance of different police activities; the second is to investigate the degree of consensus regarding these ratings. Furthermore, the practical implications of these findings for law enforcement agencies are discussed.

2. Methods

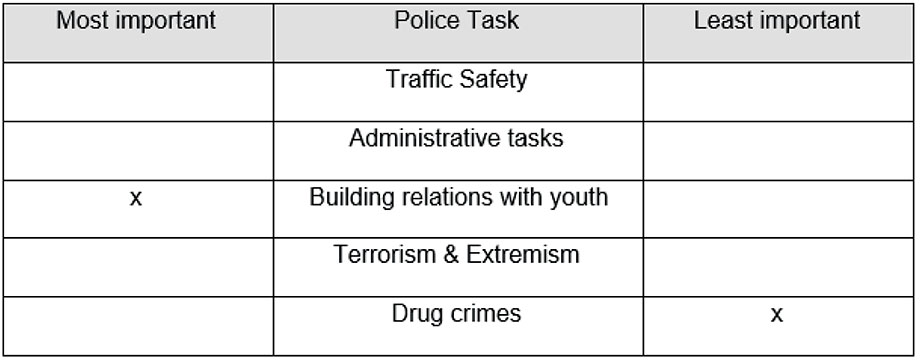

To measure the relative value that Swedish citizens attribute to different police activities, a list of 11 items representing different aspects of police work was developed into a survey (Figure 1) in a best–worst scaling (BWS) format, where five items were presented repeatedly in randomized combinations. BWS is a common method to measure preferences and can be used in various fields, e.g., patientsʼ preferences in health care (Cheung et al., 2016; Wittenberg et al., 2016) or consumer perspectives in marketing research (Louviere et al., 2013). Beginning on May 25, 2022, 2000 individuals were recruited from the SOM Instituteʼs Swedish citizen panel, of which 1002 (50.1%) chose to participate. Two reminders were sent out, and data collection ended on June 15, 2022. The sample was prestratified by age, sex and educational level, and then randomized within those strata. After removing all the participants who did not fully complete the survey, 979 participants remained. Data regarding age, type of residential area, and education level were also gathered. In the Swedish school system, three education levels are commonly used: elementary school (högstadium) is mandatory and completed by the age of 15; high school (gymnasium) is voluntary but has a high admission rate and is typically completed at the age of 19; university is a possibility thereafter.

2.1 Measures

We asked participants to evaluate the relative importance of different police areas. The respondents were provided with a series of issues related to police work and were asked to evaluate them. Specifically, they were instructed to identify what they deemed to be the least important and which they considered the most important for the police to prioritize among the selectable alternatives.

Considering the multifaceted nature of police activities, compiling a list of alternatives that represent police work without excluding anything essential part was a rather challenging task. More alternatives could certainly have been included, although we were restricted by practical limitations, meaning that we had to make some type of draft of viable alternatives. The alternatives were derived from previous studies and reports made by other national crime agencies (e.g., Higgins, 2019) as well as the priorities stated in the most recent regulatory letters issued annually by the Swedish government as a mechanism for governing the police and the formerly mentioned strategic plan for the police. The following 11 items were chosen to represent the breadth of police responsibilities: hate crimes, drug crimes, building relationship with youths, burglary, administrative tasks, gang criminality, responding to emergency calls, attending public gatherings, terrorism and extremism, crimes against women, and traffic safety. To aid understanding, two alternatives were provided with clarification: “administrative tasks” were exemplified by processes such as issuing passports, and “attend public gatherings” was exemplified by activities such as monitoring football matches or demonstrations. These items were clarified, recognizing that respondents might not possess knowledge about these issues.

When collecting data on individualsʼ opinions, the amount of background information given to participants beforehand is a crucial aspect to consider. Similarly to when assessing the publicʼs perception of questions related to justice, the level of details given to the respondent can vary. For instance, one can offer detailed information and ask respondents to form an opinion on a specific scenario, thus measuring what could be labeled as “informed justice.” Alternatively, using broader statements without specific case details can investigate respondentsʼ “general sense of justice” (see e.g., Balvig et al., 2015). In the present study, the alternatives were formulated broadly without any specific context, primarily capturing the publicʼs overall perspective on the policeʼs role and duties. This methodological choice was made to bypass the effect that various situational or case-specific aspects might have. Instead, the aim is to capture the publicʼs immediate perceptions regarding what they consider to be the primary responsibility of the police. Naturally, this methodological approach significantly affects how results are interpreted and their real-world relevance, as respondentsʼ views might shift with additional information. This was observed in the study by Higgins (2019), where the research methodology involved group discussions where participants deliberated on police priorities after initially stating their personal preferences. Through deliberating and adding contextual consideration, many participants shifted their stance into a less punitive one, and to a higher degree, advocated for a strategic and preventive approach to policing.

Another methodological aspect that requires examination is the potential for overlap among various items, which might affect the underlying assumption of ordinality. This issue is broadly applicable across different alternatives. For instance, initiatives aimed at building relationships with young people could be seen as indirectly important in preventing gang-related criminality. However, the surveyʼs objective is to investigate what citizens deem as important police priorities as such, and not to delve into the rationale behind these views. However, the risk of perceived interchangeability suggests that the distinct importance attributed to each category might be influenced by an overlap, where alternatives are viewed as essentially identical, rather than as separate. This concern might be particularly critical for the categories “Gang criminality” and “Drug crimes” due to the common association between drug offenses and gang activities. Thus, it is possible that respondents might prioritize drug crimes, considering them an aspect of gang criminality. To investigate this hypothesis, we analyzed the Spearman rho correlation between these two items. If respondents indeed consider the importance of addressing drug crimes as part of addressing gang criminality, we expect to find a positive correlation. However, our analysis did not reveal any significant positive association between these two items. That being said, the problem of overlapping items is not entirely resolved, although it also reflects a reality of police work.

2.2 Survey Design

The survey was designed in a best–worst scaling object case 1 format (BWS) with a conventional discrete choice model. When measuring preferences, BWS is generally considered superior to other common alternatives. One common method is to use Likert scales, which may suffer from the problem that the respondentsʼ frame of reference may change with each question—an issue that is likely to be particularly present in the matter of police work due to its morally charged nature, where, in some sense, “everything matters.” Another alternative could be to simply list all the alternatives and let the respondent rank the alternatives, which entails the risk of information overload and respondent fatigue. Hence, a BWS design is considered the best option (Burton et al., 2021). When using a BWS design, a list of items is produced and divided into several sets, with different alternatives occurring repeatedly. In this case, the 11 items pertaining to diverse police work were allocated across seven distinct sets. Each query consisted of a set comprising five items, whereby the participant was required to select one item deemed most significant and one item regarded as least important.

Figure 1

Example of a Survey Question.

When an item is selected as the most important or least important, it is assigned a value of 1 or -1 respectively, which is then aggregated and standardized. The remaining three items of a certain set are assigned a value of zero and thus have no quantitative effect on the standardized score but add information by being a selectable option in relation to other options. Each item appeared in three sets, except for gang criminality and traffic safety, which appeared four times each.

2.3 Analytic Strategy

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0.1, and graphs were produced in Excel. Descriptive statistics of the respondents were first presented, followed by the overall standardized BWS score. The BWS score was calculated by subtracting the number of times an alternative was selected as the least important from the number of times it was selected as the most important and then dividing the result by the number of times the alternative appeared in the survey.

In order to explore potential variations within the sample, we categorized participants separately based on three demographic variables: sex (male or female), type of residency (grouped as either city/large urban area or small urban area/rural area), and education level (initiated university studies or not). Sex has been found to be linked to political preferences, where women on group-level tend to be more left-leaning than men, a pattern that has increased over time (scb.se). Residency may be important because patterns in crime and the ratio of police officers to citizens can differ significantly between rural areas and larger urban cities. Education level is investigated, as education level has consistently shown to be positively correlated to more liberal political views (see e.g., European Social Survey, 2024) Similarly, in previous research age has been identified as a factor associated with ideological perspectives, with younger individuals tending to exhibit more liberal viewpoints. However, due to the limited representation of participants under the age of thirty in our sample, this aspect was not explored in further detail. Due to the ordinal and non-parametric nature of the data, we utilized the Mann-Whitney test to ascertain the presence of statistical significance. The criterion for determining significance was set at p-values less than or equal to 0.05. Furthermore, we conducted a comparison of mean values based on residency.

Moreover, differences that are not contingent on specific demographic characteristics may exist. Therefore, latent class analysis (LCA) was employed as a fourth step. The fundamental principle of LCA is that observed variables (or indicators) are influenced by an unobservable categorical variable (in this case, e.g., political orientation or views on the policeʼs broader role in society). This latent variable represents the classification of individuals or cases into distinct groups based on their similarities in response patterns to observed variables. However, the analysis did not reveal any significant groupings (silhouette coefficient = 0.2). Hence, the results are not presented here.

3. Results

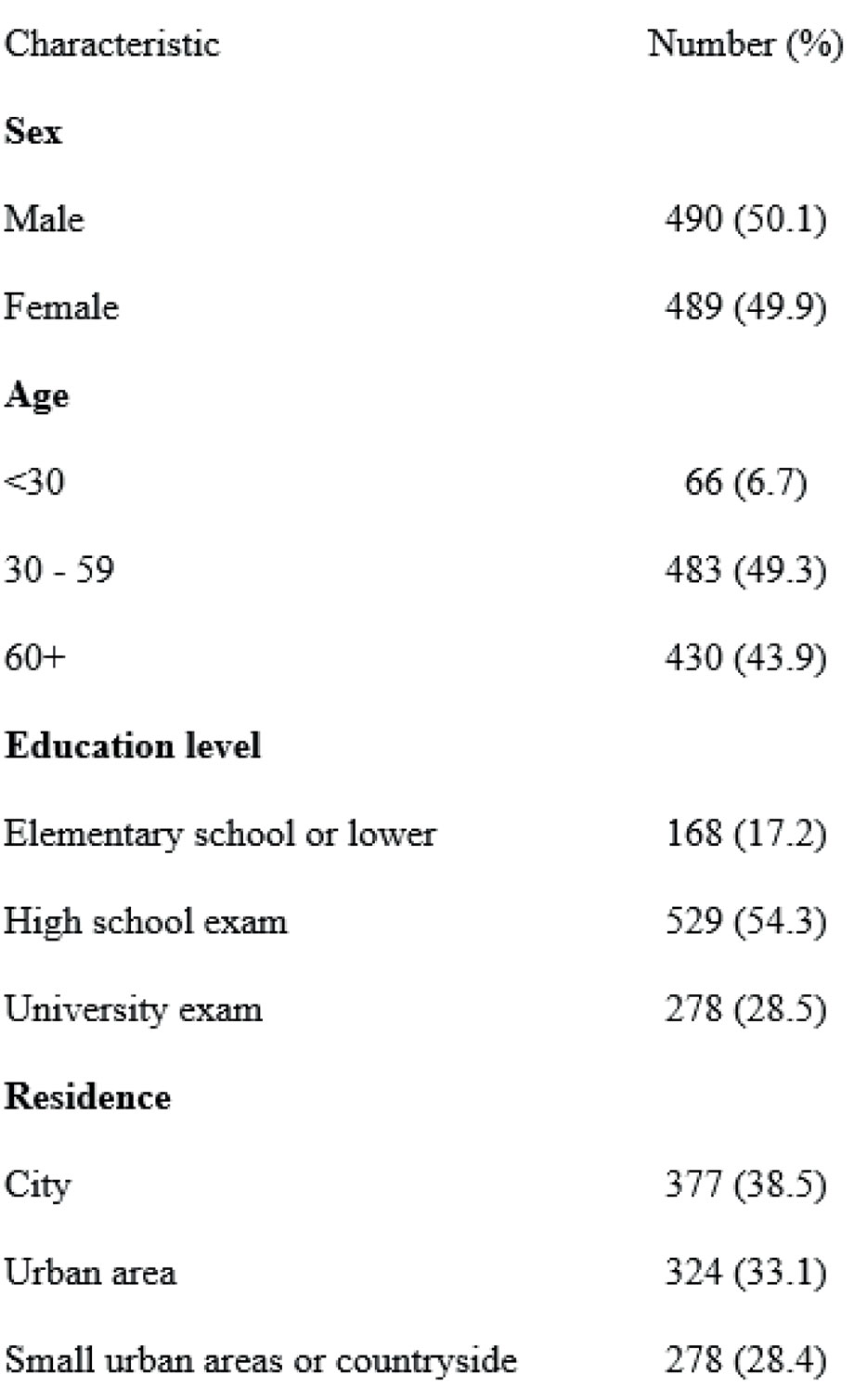

In total, 979 participants assessments were analyzed: 50.1% of participants were women and 49.9% were men (see Table 1). The participants were distributed across all levels of education and place of residence, although the sample size was slightly lower in the lowest age category.

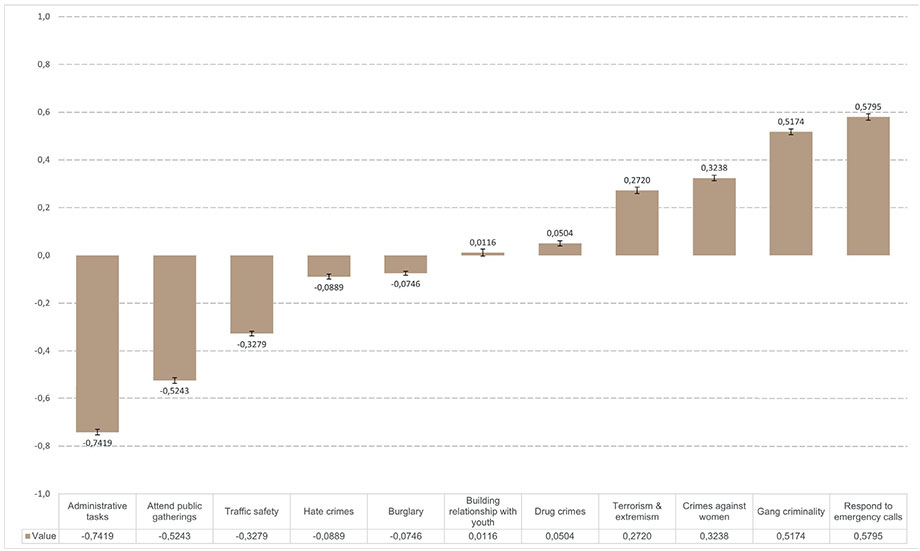

The main features of the data were explored by constructing a standardized BWS score that is presented in Figure 2. To investigate the generality of the assigned values, the standard error is presented for each alternative, as well as the mean value depending on sex and education level and residency.

Table 1

Sample Characteristics

On aggregate level, responding to emergency calls was the most important, followed by gang criminality, crimes against women, terrorism and extremism, drug crimes, building relationships with youth, burglary, hate crimes, traffic safety, attending public gatherings, and administrative tasks. The consistently low standard errors for all alternatives imply a substantial consensus among respondents regarding the prioritization of specific choices.

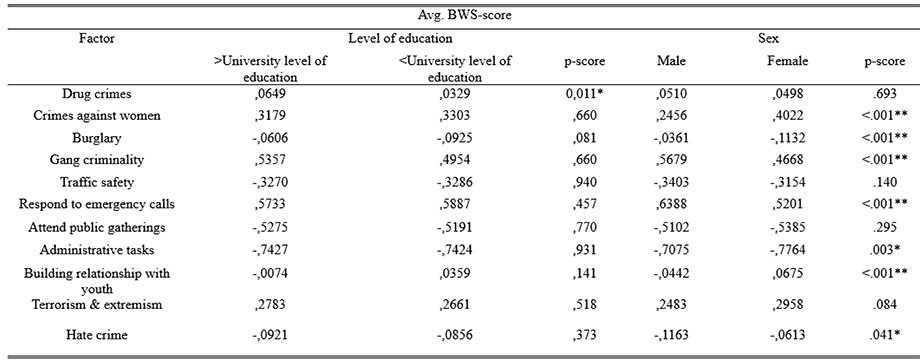

To investigate disparities in prioritization tendencies among different groups, differences between individuals grouped on sex and educational level, respectively. Results are presented in Table 2. In analyzing the impact of educational attainment, it is notable that significant differences were only observed in drug crimes where the group with higher level of education assigned a lower mean score. This underscores the relative consistency in the hierarchical arrangement of priorities, irrespective of oneʼs educational background. In contrast, the differentiating factor became more pronounced when examining variances between men and women. In this regard, significant differences manifested across seven alternatives: crimes against women, burglary, gang criminality, responding to emergency calls, administrative tasks, hate crimes and building relationships with youth. Compared to the female group, the male group assigned higher values to the following items: drug crimes, burglary, gang criminality, responding to emergency calls, attending public gatherings and administrative tasks. Consequently, the female group assigned relatively higher values to the remaining items: crimes against women, traffic safety, building relationships with youths, terrorism & extremism and hate crimes.

Figure 2

Standardized Scores for the 11 Police Tasks.

Table 2

Results from Mann-Whitney U-test.

Although significant on a 0.05 level, these differences were generally minor, with the exception of crimes against women, which exhibited a significant difference of 15.7%. Although male and female respondents demonstrated similar patterns in terms of their prioritization of individual alternatives, there were differing patterns in the emphasis placed on certain characteristics of the alternatives. Overall, men tended to favor traditional “crime-fighting” activities such as responding to calls, fighting gang crime, and investigating burglaries. Women placed slightly higher value on other issues, such as protecting certain groups, as indicated by their higher valuing of crimes against women and hate crimes or working with community-oriented aspects of policing, such as building relationships with young people.

Figure 3

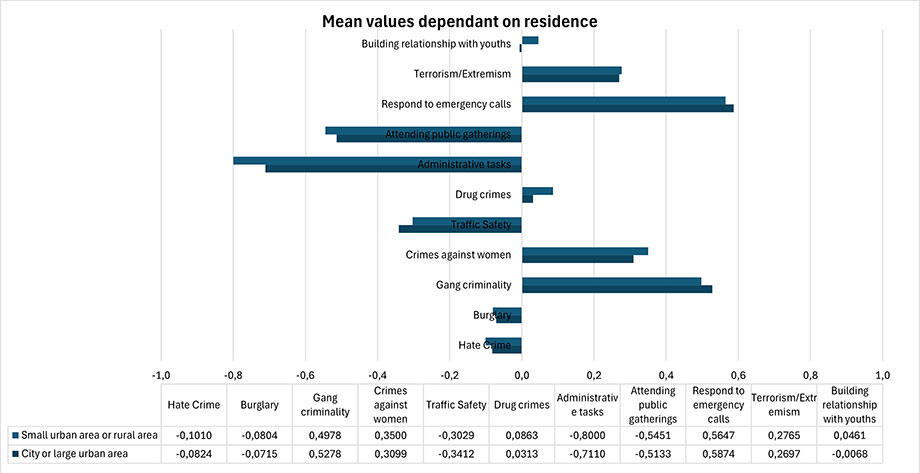

Another aspect worth examining is the impact of residency on mean values. In our analysis, we found the mean values to be remarkably similar, with the greatest variation being 0.089, observed in administrative tasks. Therefore, opinions on these matters, as measured in our survey, appear to be largely unaffected by residency.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we investigated how citizens prioritize between different areas of police work. When examining the distribution of the assigned value of individual items, citizens express the highest importance for a swift response to emergency calls. Traditionally, an assumption has been that the allocation of resources toward responding to emergency calls is inherently justified due to its perceived importance (Pate et al., 1976). However, a contrasting view could be that dedicating staff and resources to maintain consistently short response times could come at the cost of other aspects of police services, such as crime investigation or community engagement activities. Our data show that, if considering the views of the public, it may indeed be worth the effort to prioritize responding quickly to calls. Hence, maintaining a sizable force for emergency call response seems vital. While our survey specifically measured responses to emergency calls, it is worth noting that a substantial proportion of calls for services are neither serious nor crime-related (Boulton et al., 2017; Ratcliffe, 2021; Wilson, 2013). This suggests that alternative approaches might also be suitable. For instance, the objective of reducing response times could be achieved by an increase in police presence on the streets, as it increases the likelihood of geographic proximity to the incident. This proposition aligns well with the preferences expressed by citizens in previous studies, as police officer visibility has commonly been found to be regarded as important by citizens (Liederbach et al., 2008; Webb & Katz, 1999).

After responding to emergency calls, dealing with gang criminality is the most important police part of police work, according to citizensʼ views. This is not surprising. Not only can gang criminality be assumed to be high on impact, but gang-related violence is at extreme levels with Swedish measures, but also compared with other European countries (Brå, 2021; Sturup et al., 2019; Westfelt, 2022). Gang criminality has also received considerable coverage in Swedish as well as international media (Svenska institutet, 2023). Moreover, crimes that are commonly linked to criminal gangs, such as shootings, serve as appropriate instances of the concept of signal crimes (Innes & Fielding, 2002). This is characterized by their effect on the publicʼs perceived sense of safety, which seems to be confirmed by the increase in concern over crime in society (Brå, 2023). Although few people are likely to have direct experience of gang criminality themselves, media coverage is likely to have a large impact on how urgent different areas of police work are perceived to be. This indicates that self-lived experiences are not necessarily the driving factor for preferred priorities on a general level.

Among the selectable alternatives, crimes against women were considered third most important. Notably, when the data was disaggregated by sex, men assigned a greater significance to counterterrorism and extremism compared to crimes against women. Conversely, crimes against women held an even higher rank among female participants. This observation suggests that while respondents demonstrate a willingness to consider interests of the common, individual perspectives may diverge based on personal attributes on some specific issues. The observed difference may be driven by self-interest, group affiliation, or other factors. Although this issue was not within the scope of the current study, it is a well-known fact that women are more worried about being the victim of a sexual crime compared to men, aligning with the rate of victimization. This can explain some of the differences in general fear of crime, as opposed to actual victimization, between men and women (Mellgren & Ivert, 2018). This in turn suggests that some personal attributes affect both fear and concern and prioritization.

At the bottom of the list, one finds activities such as administrative tasks, attendance at public gatherings, and traffic safety—items relating to the social or order function of the police. It is intriguing that traffic safety is considered one of the least important, despite the fact that annually, approximately twice as many people die in traffic accidents compared to lethal violence. This may reflect public views on what the essential function of the police is—specifically, managing situations where the use of force is a key element. If we consider public opinion, it might be logical to transfer certain parts of the policeʼs responsibilities, such as passport processing or traffic safety, to another agency, similarly to how parking regulations are enforced. Compared to the emphasis on areas that are expressed by the police in strategic plans and regulatory letters, there seems to be an agreement between the public and the police, with some minor disparities. The mission of the police as expressed in the Police Act encompasses a wide variety of responsibilities, and all are considered important to prioritize; the same is expressed in the strategic plans. However, some areas must be prioritized when the situation demands it.

Other activities that would fit within the control function of the police, such as drug use or traffic safety, are found in the middle of the chain, while items that fit well within the social function are found at the bottom. This may appear self-evident: the basic function of the police is to prevent and solve crimes. However, how this should be achieved is not as straightforward. Summarizing citizensʼ views on the matter, it can perhaps be phrased such that responsibilities that are further down the causal chain of crime are not regarded as the primary obligation of the police force (Webb & Katz, 1997). However, this may reflect the notion that individuals are not well informed about the preventive measures carried out by the police force (Salmi et al., 2005). Nonetheless, a potential contradiction may arise from the discrepancy between modern approaches to policing and public opinion, as there may be strategic justifications for prioritizing certain areas that citizens do not immediately perceive as urgent. While community-oriented policing (COP) aims to deal with problems rather than incidents, support the public, and maintain order while fostering robust community relations, most citizens seem to place greater emphasis on items related to a “standard model” of policing (Higgins et al., 2017; Lum & Koper, 2017). Potentially, this presents a paradox, considering that citizen satisfaction constitutes a central objective of COP. Generally, police activities characterized as proactive, location-based, and focused have been demonstrated to effectively reduce crime (Lum & Koper, 2017). In contrast, rapid responses to calls have not shown to have a deterrent effect on crime, although some recent evidence suggests it may increase clearance rates (Vidal & Kirchmaier, 2018). Similarly, strong community relations have been shown to improve clearance rates (Carter & Carter, 2016; Lum & Koper, 2017), in part because of citizensʼ improved willingness to cooperate with police. Although, this effect is indirect and therefore unlikely to be regarded highly by the public in terms of prioritization. This suggests that decision-makers within law enforcement may have to handle trade-offs in which evidence-based strategies and public opinion diverge. Alternatively, greater efforts could be devoted to informing the public about the strategic foundations underpinning police decisions, particularly in cases in which the gap between police actions and citizensʼ perceptions is significant. Educating the public on the rationale behind specific strategies may help bridge this divide and enhance the understanding of the complexities involved in policing.

The second objective of the current study was to investigate the extent of consensus concerning the relative importance of various aspects of policing. Logically, prioritization necessitates deprioritization, meaning that law enforcement ought to incorporate the values and expectations of the general population in its prioritization. Consequently, ensuring that police actions align with public concerns may be vital to maintaining legitimacy. If the degree of consensus is low, there is a potential risk that the policeʼs activities and how they are prioritized become politically charged and associated with perceived injustice; if low enough, the public is a questionable premise to begin with. Regarding this issue, our data indicates a high degree of general agreement on how the police should prioritize. This notion is supported by the fact that the standard error is low: groups of different demographic characteristics such as sex, educational level, or residency responded similarly. Survey responses could not be significantly clustered, meaning that there are no distinct groups representing differing viewpoints. Additionally, prior research reports similar results, despite variations in which items were included and in which context the study was conducted. However, in the current study it is important to consider that the level of consensus is something that is observed within the framework of the surveyʼs design. We have utilized categories that are broadly defined, which increases the probability of one-sidedness in the answers. Conversely, if one has options that provide very specific information, dividing lines that are not prominent here might have been identified. Additionally, since participants were required to prioritize the options we presented, there may be diverse opinions on other policing aspects that were not presented in the survey.

Another aspect relating to the generalizability of the findings is to consider whether our sample can be said to represent “the public.” Although our sample was stratified and randomly selected to represent society as a whole, the response rate was approximately 50%, indicating the possibility of a systemic difference between those who chose to participate and those who did not. Moreover, the sample was gathered from Medborgarpanelen, which is a web-based panel of people who have chosen to answer questions by email a few times a year. It is plausible that the individuals included in this survey predominantly belonged to a segment of society that initially possessed a high level of trust in authorities and may have had different experiences of crime and law enforcement than other parts of the population. Conversely, groups with lower levels of trust in the police may not be adequately represented in this survey. This assertion is supported by the fact that trust in the police is comparatively higher in our sample than that reported in the annual survey conducted by Brå (2022), which covers a larger part of the population and employs a different methodology for collecting responses from people. Whether individualsʼ trust in authorities influences their perceptions of which priorities are deemed the most important has not been thoroughly examined in the existing literature. In conclusion, our findings indicate a high degree of consensus, but this should be interpreted with caution.

When interpreting the survey results, it is critical to reflect on the selection and phrasing of the items included. As previously mentioned, capturing every aspect of policing within a single survey is not feasible, meaning that some essential options might be excluded. In this case, investigating crime has not been included, despite being commonly presented in previous research. Hence, choosing not to include it is likely to affect the results. Given the consistently high ratings for crime investigation across various studies, it is reasonable to assume it would have received similar importance in our survey. Including it would potentially add more weight to the traditional policing perspective. This highlights the importance of considering which items are included, or not included, when drawing conclusions based on a survey. The labeling of activities is an equally important aspect when analyzing survey results. For example, “Building relations with youths” suggests an emphasis on long-term crime prevention and community engagement, a cornerstone of community-oriented policing. In contrast, alternative phrasings, like “Keeping children and young people safe,” might evoke a more immediate, protective stance, underscoring the urgency of direct crime prevention. Such nuances in language underscore the complexity of investigating public safety priorities, where the balance between addressing current challenges and investing in preventive measures becomes an important consideration. Our findings must therefore be interpreted with an awareness of how terminological choices can shape perceptions of policing priorities.

With the caveats above in mind, there is good reason to believe that, in line with the reasoning of Higgins (2019), perceived impact and harm are critical determinants of how important a certain activity is considered to be. The responses captured in our study reflect immediate perceptions, which could potentially shift if respondents were provided with more information about specific examples or the strategic priorities behind certain police activities. However, gaining an understanding of immediate perceptions is valuable because it provides insights into the views of citizens as such. It is reasonable to assume that the average citizen may not be deeply familiar with the intricacies of police operational strategies or the specific challenges and considerations that guide the prioritization of various tasks. This snapshot of public opinion, while potentially subject to change with increased awareness and understanding, is crucial for estimating the present view on police role and its alignment with community expectations.

What image of the police role emerges if one starts from the publicʼs responses? From the study it is evident that the public assigns lesser importance to administrative tasks within the police force. This might reflect a broader expectation that police officers should be more present in the community, engaging directly in activities that protect and serve citizens rather than being burdened with paperwork (Loader, 2014). Citizens seems to advocate for a more “boots on the ground” approach in which police visibility and action are clear and present. The emphasis on building relationships with youths and addressing crimes against women fits well within the community-policing framework. On the other hand, the high importance placed on responding to emergency calls and tackling terrorism and extremism as well as gang criminality aligns more closely with traditional policing models, which are centered around authority, response to crimes, and maintenance of public order. In terms of the policeʼs role, this implies the need for a careful balance: they must project a level of assertiveness that deters crime and maintains order, while also engaging in community-oriented strategies that prevent criminal activity and build strong police–citizen relations. This balanced approach is likely to enhance the publicʼs perception of the police as legitimate and trustworthy, elements that are fundamental to effective policing. Such a balance could perhaps be realized through the “comprehensive paradigm” suggested by van Dijk et al. (2015). This paradigm challenges the binary distinction of “control” versus “consent” or, in similar terminology, between fighting crime and engaging in community-oriented policing. In this perspective, transparency, accountability, and professionalism should be core values in policing. Embracing “hard” control measures, such as using force during disturbances, detaining individuals as needed, and stopping and questioning suspects—some of whom will be found innocent—is essential for maintaining order. However, these measures must operate within the framework of ethical conduct and professionalism to support the policeʼs overarching goal of community service. An important aspect of this perspective is referred to as “honest policing.” This implies that police leadership openly communicates the multifaceted nature of their responsibilities to the public. Such an approach does not view enforcement and community engagement as opposing forces but rather as interconnected facets of a comprehensive public service mission. Understanding and integrating citizensʼ perspectives into policing strategies may be an important part of this process.

That being said, the process of establishing operational priorities within policing is intricate and involves managing numerous competing demands. Day-to-day policing is often reactive in nature, allocating a significant portion of their resources to addressing incidents as they arise. Moreover, the police are legally obligated to investigate crimes falling within the principle of general prosecution. Hence, this type of research is unlikely to generate a result that has the same direct influence as market research has in business governance in the private sector, which is driven primarily by cost–benefit analysis and a “customer satisfaction mindset.” However, the Swedish police do possess a substantial degree of discretion (Landström et al., 2020) that facilitates the translation of theoretical priorities into actionable measures. Moreover, steps are being taken toward proactive policing (Polismyndigheten, 2022), which may give further space for active prioritization in the sense that decisions on resource allocation precede what to proactively work to prevent.

The extent to which public opinion should impact decision-making in policing is outside of the scope of the current study, but a foundational understanding of the publicʼs viewpoints, and their potential discrepancies in relation to the policeʼs priorities, may be important to consider when balancing different demands in modern policing. We have shown that understanding citizensʼ viewpoints when establishing priorities may have potential to improve policing. While our study serves as a foundational effort, there remains significant scope for further research to enrich our understanding. Building on the premise that understanding citizensʼ viewpoints can enhance policing strategies, further research could benefit from examining how providing additional information may change public perceptions. Moreover, this could provide insights into reasonings leading to a specific viewpoint. Additionally, there is a notable gap in research regarding the connection between policing priorities and trust—a factor frequently recognized as crucial for effective policing. However, the topic is inherently elusive. Society is rapidly changing, different problems emerge and need to be handled with varying urgency, ultimately influencing the priority of some areas over others in practice. The problem with deadly group-related violence has driven the development toward a more repressive crime policy in Sweden, and this prioritization seems to have the publicʼs support on a foundational level. The nature of policing, however, remains a complex issue.

References

-

Andersson, F.,Demker, M.,Mellgren, C., &Öhberg, P.(2021). Kriminalpolitik – lika hett som man kan tro. InU. Andersson,A. Carlander,M. Grusell&P. Öhberg(Eds.),

Ingen anledning till oro (?)

.SOM-institutet, Göteborgs universitet

. -

Andersson, U.,Öhberg, P.,Carlander, A.,Martinsson, J., &Theorin, N.(2023). Ovisshetens tid. InU. Andersson,P. Öhberg,A. Carlander,J. Martinsson, &N. Theorin(Eds.),

Ovisshetens tid

(pp. 7-21).SOM-institutet, Göteborgs universitet

. -

Asplund, F.(2023). Polischefen: Mängdbrott prioriteras bort när gängkriminalitet dominerar.

SVT Nyheter

. URL: https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/sormland/sodermanlands-polisomradeschef-om-riksrevisionens-kritik -

Balvig, F.,Gunnlaugsson, H.,Jerre, K.,Tham, H., &Kinnunen, A.(2015). The public sense of justice in Scandinavia: A study of attitudes towards punishments.

European Journal of Criminology

, 12 (3), 342-361. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370815571948 -

Beck, K.,Boni, N., &Packer, J.(1999). Use of public attitude surveys: What can they tell police managers?

Policing

, 22(2), 191–213. -

Boulton, L.,McManus, M.,Metcalfe, L.,Brian, D., &Dawson, I.(2017). Calls for police service: Understanding the demand profile and the UK police response.

The Police Journal

, 90(1), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X16671032 -

Brå (Brottförebyggande rådet) (2021).

Gun homicide in Sweden and other European countries

. Report 2021:8.Brottsförebyggande rådet

:Stockholm

. -

Brå (Brottsförebyggande rådet) (2022).

Nationella trygghetsundersökningen 2021. Om utsatthet, otrygghet och förtroende

. Rapport 2022:9.Stockholm

:Brottsförebyggande rådet

. -

Brå (Brottsförebyggande rådet) (2023).

Nationella trygghetsundersökningen 2022. Om utsatthet, otrygghet och förtroende

. Rapport 2023:9.Stockholm

:Brottsförebyggande rådet

. -

Burton, N.,Burton, M.,Fisher, C.,González Peña, P.,Rhodes, G., &Ewing, L.(2021). Beyond Likert Ratings: Improving the Robustness of Developmental Research Measurement Using Best–Worst Scaling.

Behavior Research

, 53, 2273–2279. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-021-01566-w -

Carter, D. L., &Carter, J. G.(2016). Effective police homicide investigations: Evidence from seven cities with high clearance rates.

Homicide Studies

, 20(2), 150–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767915576996 -

Cheung, K. L.,Wijnen, B. M. F.,Hollin, I. L.,Janssen, E. M.,Bridges J. F.,Evers, S. M. A. A., &Hiligsmann, M.(2016). Using best-worst scaling to investigate preferences in health care.

Pharmacoeconomics

. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0429-5 -

Cohen, S.(2011).

Folk devils and moral panics

(1st ed.).Routledge

. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203828250 -

Demker, M., &Duus-Otterström, G.(2007). Kriminalpolitik – inte så hett som man kan tro. InS. Holmberg&L. Weibull(Eds.),

Det nya Sverige

.SOM-institutet, Göteborgs universitet

. -

European Social Survey. (2024). ESS data portal.

European Social Survey

. Retrieved June 18, 2024, from https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data -

Finstad, L.,Mellgren, C.,Andersson, J., &Holmberg, J.(2023).

Polis—Vad är det?

Studentlitteratur AB

. -

Goldstein, H.(1990).

Problem oriented policing

.McGraw-Hill Publishing

. -

Higgins, A.(2019). Understanding the publicʼs priorities for policing.

The Police Foundation

. -

Higgins, A.,Hales, G., &Chapman, J.(2017) Police Effectiveness in a changing world. Luton Report.

The Police Foundation

. -

Innes, M., &Fielding, N.(2002). From community to communicative policing: ʻSignal crimesʼ and the problem of public reassurance.

Sociological Research Online

, 7(2), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.724 -

International Association of Chiefs of Police. (2018).

Building trust between the police and the citizens they serve

. Retrieved from https://www.theiacp.org/sites/default/files/2018-08/BuildingTrust_0.pdf -

Landström, L.,Eklund, N.&Naarttijärvi, M.(2020). Legal limits to prioritisation in policing – Challenging the impact of centralisation,

Policing and Society

, 30:9, 1061–1080, https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2019.1634717 -

Leijman, S.(2023).

Efter senaste våldsvågen – lågt förtroende för polisens förmåga att minska gängkriminaliteten

.SVT Nyheter

. URL: https://www.svt.se/nyheter/inrikes/efter-senaste-valdsvagen-lagt-fortroende-for-polisens-formaga-att-minska-gangkriminaliteten. -

Liederbach, J.,Fritsch, E. J.,Carter, D. L.&Bannister, A.(2008). Exploring the limits of collaboration in community policing: A direct comparison of police and citizen views.

Policing: An International Journal

, Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 271–291. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510810878721 -

Liljegren, A.,Berlin, J.,Szücs, S., &Höjer, S.(2021) The police and ʻthe balanceʼ—Managing the workload within Swedish investigation units.

Journal of Professions and Organization

, 8(1), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/joab002. -

Lipsky, M.(1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services.

New York

:Russell Sage Foundation, 1980

. (1980).Politics & Society

, 10(1), 116–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/003232928001000113 -

Loader, I.(2014). Why do the police matter? InJ.M. Brown(Ed.)

The future of policing

,NY

:Palgrave

, pp. 40–51. -

Louviere, J.,Lings, I.,Islam, T.,Gudergan, S., &Flynn, T.(2013). An introduction to the application of (case 1) best–worst scaling in marketing research.

International Journal of Research in Marketing

, 30(3), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.10.002 -

Lum, C. M., &Koper, C. S.(2017).

Evidence-based policing: Translating research into practice

.Oxford University Press

. -

Lum, C.,Wellford, C.,Scott, T.,Vovak, H.,Scherer, J. A., &Goodier, M.(2023). Differences between high and low performing police agencies in clearing robberies, aggravated assaults, and burglaries: Findings from an eight-agency case study.

Police Quarterly

, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10986111231182728 -

Lundborg Andersson, H.(2018, May 9). Ny mätning: De är viktigaste valfrågorna.

Expressen

. Retrieved from https://www.expressen.se/nyheter/val-2018/ny-matningde-ar-viktigaste-valfragorna/ -

Mellgren, C., &Ivert, A.-K.(2019). Is Womenʼs Fear of Crime Fear of Sexual Assault? A Test of the Shadow of Sexual Assault Hypothesis in a Sample of Swedish University Students.

Violence Against Women

, 25 (5), 511-527. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218793226 -

Millie, A.(2014). What are the police for? Re-thinking policing post-austerity. InJ. Brown(Ed.),

The future of policing

(pp. 52–63).Routledge

. -

Pate, A. M.,Ferrara, A.,Bowers, R. A., &Lorence, J.(1976). Police response time.

The Police Foundation

. https://www.policinginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Pate-1976-Police-Response-Time.pdf -

Polismyndigheten (2022).

Polismyndighetens strategi för det brottsförebyggande arbetet

. PM 2022:12. -

Polismyndigheten. (2023).

Polismyndighetens strategiska verksamhetsplan 2020–2024

.Polismyndigheten

. -

Punch, M.(2015). What really matters in policing?

European Police Science and Research Bulletin

, 13, 9–18. -

Ratcliffe, J. H.(2021). Policing and public health calls for service in Philadelphia.

Crime Science

, 10(5). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-021-00141-0 -

Riksrevisionen. (2023).

Polisens hantering av mängdbrott – en verksamhet vars förmåga behöver förstärkas (RiR 2023:2)

.Riksrevisionen

. -

Roos, M., &Israelsson, L.(2018, February 14). Lag och ordning är väljarnas viktigaste valfråga 2018.

Expressen

. -

Salmi, S.,Voeten, M., &Keskinen, E.(2005). What citizens think about the police: Assessing actual and wished-for frequency of police activities in oneʼs neighborhood.

Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology

, 15(3), 188–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.810 -

Skogan, W. G.(1996). The police and public opinion in Britain.

American Behavioral Scientist

, 39(4), 421–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764296039004006 -

Socialdemokraterna. (2017, April 26).

Partistyrelsen föreslår 10,000 fler polisanställda

. Retrieved from https://www.socialdemokraterna.se/nyheter/nyheter/2017-04-26-partistyrelsen-foreslar-10-000-fler-polisanstallda -

Sturup, J.,Rostami, A.,Mondani, H.,Gerell, M.,Sarnecki, J., &Edling, C.(2019). Increased gun violence among young males in Sweden: A descriptive national survey and international comparison.

European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research

, 25(4), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-018-9387-0. -

Svenska institutet. (2023).

Bilden av Sverige utomlands 2022

.Stockholm

:Svenska institutet (SI)

; Årsrapport från Svenska institutet Diarienummer: 0122/2023. [accessed August 28, 2023]. Available from: https://si.se/app/uploads/2023/03/bilden-av-sverige-2022-tillganglighetsanpassad.pdf. -

Tyler, T. R.(2006).

Why people obey the law

.Princeton University Press

. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1j66769 -

van Dijk, A.,Hoogewoning, F., &Punch, M.(2015).

What matters in policing?: Change, values and leadership in turbulent times

(1st ed.).Bristol University Press

. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t894mz -

Vidal, J,Kirchmaier, T, (2018) The effect of police response time on crime clearance rates.

The Review of Economic Studies

, Volume 85, Issue 2, April 2018, Pages 855–891. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2630987 -

Westfelt, L.(2022). Den svenska våldsbrottsutvecklingen i ett europeiskt perspektiv. InA. Rostami&J. Sarnecki(Redaktörer),

Det svenska tillståndet: En antologi om brottsutvecklingen i Sverige

(pp. 64–96).Lund

:Studentlitteratur

. -

Webb, V. J.andKatz, C.M.(1997). Citizen ratings of the importance of community policing activities.

Policing: An International Journal

, Vol. 20 No. 1, pp. 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639519710161980 -

Wilson, J. Q.(2013).

Thinking about crime

.Basic Books

. -

Wittenberg, E.,Bharel, M.,Bridges, J. F.,Ward, Z., &Weinreb, L.(2016). Using best-worst scaling to understand patient priorities: A case example of Papanicolaou tests for homeless women.

Annals of family medicine

, 14(4), 359–364. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1937