Police Officers’ Reflections on Using Alternative and Augmentative Communication During Investigative Interviewing of People with Speech, Language and Communication Needs

Professor

Department of Vocational Teacher Education, Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway

veerle.garrels@oslomet.noSpecial educational therapist

University Hospital of North Norway (UNN), Tromsø, Norway

Clinical occupational therapist

Nordland Hospital Trust (Nordlandssykehuset), Bodø, Norway

Publisert 17.12.2025, Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing 2025/1, Årgang 12, side 1-20

People with speech, language, and communication needs (SLCN) frequently experience barriers in their meetings with the legal system, and equal access to justice is not yet a reality for them. One area for improvement seems to be police officers’ competence about SLCN and how to provide support for people with SLCN during investigative interviewing. In this study, eight Norwegian police officers participated in focus-group interviews to share their perspectives on using alternative and augmentative communication (AAC) when interviewing victims with SLCN. Participants highlighted the need for information about SLCN and AAC at all levels of the legal system, so that support needs of people with SLCN could be better understood and supported also beyond the context of the investigative interview. Moreover, findings indicate that participants were highly motivated to give a voice to people with SLCN so that they could be heard in the legal justice system. At a practical level, participants identified challenges with finding appropriate graphic symbols to support communication during the police interview, and they suggested building an expert network for police officers who conduct AAC-facilitated interviews.

Keywords

- communication challenges ;

- alternative communication ;

- investigative interviewing ;

- police ;

- legal system ;

- disability

1. Introduction

According to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006), people with disabilities have the right to effective access to justice on an equal basis with others, and they have the right to procedural and age-appropriate support during any contact they have with the legal system. This commitment to the right to effective access to justice was reinforced with Goal number 16 of the Sustainable Development Goals, which emphasizes equal access to justice as essential for protecting the rights of individuals and for ensuring that vulnerable populations are not marginalized or mistreated (United Nations, 2015). However, there still remains a gap between ambitions and reality: People with disabilities are disadvantaged by a legal system that does not meet their support needs, and encounters with the legal justice system are often found to be disabling (Gormley & Watson, 2021). Given the fact that people with disabilities are disproportionately often involved with the judicial system (see, e.g., Baggio et al., 2018; Geijsen et al., 2018), this is particularly alarming.

Research indicates that people with disabilities face various barriers during their contacts with law enforcement. Some of these barriers pertain to a lack of disability knowledge and awareness among law enforcement officials, as well as insufficient support during contact with the legal justice system (Gormley & Watson, 2021; Gulati et al., 2020), which may lead to inconsistencies in how people with disabilities are met by law enforcement officials (Edwards et al., 2015). In addition, people with disabilities may experience procedural barriers when faced with complex and intimidating legal procedures, and information is often found to be inaccessible, confusing, and difficult to comprehend (Edwards et al., 2015). Byram (2022) further identified various physical barriers that hampered access to courts, and Gulati et al. (2020) highlighted an unmet need for the provision of procedural and emotional support. These barriers seem to exist regardless of whether people with disabilities are in the role of victims, witnesses, or offenders, resulting in a legal justice system that is largely non-inclusive and inaccessible to them.

People with speech, language, and communication needs (SLCN) may experience even more pervasive barriers in their encounters with law enforcement than people with other types of disabilities. As Edwards et al. (2015) state, the principle of orality is key in the legal system. During contact with law enforcement, it is generally considered beneficial to be able to express oneself freely and coherently, and this is often challenging for people with SLCN. A lack of understanding of speech-language pathology among law enforcement officials may affect the credibility and perceived validity of the statements of people with SLCN. Research indicates that contact with the criminal justice system may be compromised for people with SLCN (see, e.g., LeVigne & Van Rybroek, 2014). Hence, effective access to justice is not yet a reality for this population.

To address this unequal access to justice, the United Nations Convention on the Right of Persons with Disabilities (2006) obliges States Parties to promote appropriate training for those working in law enforcement. Yet, nearly two decades on, research continues to identify a need for training and tools to equip law enforcement officers with the skills to interact proficiently with people with disabilities (see, e.g., Diamond & Hogue, 2023). However, few evidence-based training interventions exist, and there is a paucity of research that can inform law enforcement about which training may be appropriate and effective. In particular, specialized training related to SLCN seems warranted. Therefore, this study investigates how Norwegian police investigators respond to an advanced training course on conducting facilitated investigative interviews with the use of alternative and augmentative communication (AAC).

2. Aim of the study

This study explores Norwegian police officers’ perspectives on the possibilities and challenges of conducting AAC-facilitated interviews for people with SLCN. The study captures the perspectives of participants immediately after they had completed an advanced training course on this topic. Since most of the participants had not yet gained practical experience with AAC-facilitated interviews at the time of the data collection, the study looks first and foremost into their theoretical reflections regarding the challenges and potential of such interviews. Thus, this study presents participants’ perspectives, based on their theoretical knowledge gathered during the course as well as on their prior professional experience with facilitated investigative interviewing. The study is guided by the following research question:

Which potential and challenges do Norwegian police officers see in using AAC-facilitated interviews for people with SLCN?

The study limits itself to exploring the use of AAC for people with SLCN, when they are alleged victims of crime. Hence, participants in the study were not asked to consider AAC-facilitated interviews for suspects with SLCN.

3. Speech, language and communication needs

SLCN is an umbrella term for a wide range of difficulties that affect a person’s ability to communicate and interact with others (Bishop et al., 2017). For communication to be successful, one needs not only the ability to pay attention and listen but also the receptive skills that enable vocabulary and syntax to be decoded and understood. Moreover, adequate communication entails the ability to convey ideas through spoken language (i.e., expressive language), the ability to produce speech sounds and produce words in a fluent manner, and the ability to communicate in a socially accepted manner, i.e., knowing the unspoken rules of social, verbal, and nonverbal conversation (Coles et al., 2017). Deficits in any of these areas may lead to communication difficulties. Thus, SLCN refers to difficulties with any aspect of communication, but it does not explain what causes the communication challenges nor does it provide direction for treatment. Instead, SLCN is a superordinate category that informs us that a person may require extra help with communicating. Hence, the term SLCN can be useful for those who plan services (e.g., educational services but also legal services), since the presence of SLCN indicates that communication support may be necessary (Bishop et al., 2017).

In some cases, SLCN may stem from a hidden condition that often remains undiagnosed and untreated (such as, e.g., developmental language disorder, DLD), while in other cases, it may be the result of a more noticeable impairment, such as fluency disorders (stuttering) or aphasia. For some people, SLCN is their primary or only challenge, which is often the case with conditions like DLD or stuttering, but for others, it may be symptomatic of another condition, for instance, autism, intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, or fetal alcohol syndrome (Bercow, 2008).

While SLCN is commonly used to refer to challenges with speech, language and communication in children and young people, it is acknowledged that many of these challenges persist in adulthood and that some people with SLCN will need lifelong communication support (Bercow, 2008). Furthermore, people with SLCN may also experience challenges in other areas than communication, such as executive functioning, and they may therefore benefit from additional support during their interaction with others (Kapa & Plante, 2015). Such support may include taking regular breaks, breaking down information into manageable chunks, and providing tools to offload working memory.

Common for all people with SLCN is that the use of communication support, such as AAC, may ameliorate their difficulties with communicating, and some people with SLCN may depend completely on AAC for their communication with others. Hence, communication partners who are knowledgeable about SLCN and who are competent in providing communication supports such as AAC, can contribute to more successful communication. This underscores the relational and reciprocal nature of communication.

3.1 Alternative and augmentative communication

AAC is an umbrella term for visual communication forms, used in direct communication with others as a supplement or alternative to spoken language. AAC refers to various ways of supporting communication between individuals who face difficulties communicating (i.e., expressing themselves verbally in a way that is understood by others and/or understanding the spoken language of others) and people in their surroundings. Ways of supporting spoken language include the use of manual signs or graphic symbols printed on paper (communication boards or communication books) or entered on a tablet or speech device with synthetic speech (Beukelman & Light, 2020, ch. 1).

Whereas few hearing people are familiar with manual signs, the use of graphic symbols is more accessible to most people, as they usually consist of an image and a written gloss under or above the image. AAC comprises various graphic communication systems, such as Picture Communication Symbols, the Widgit Symbol System, or Blissymbolics. Most of these systems use either white silhouettes and white gloss on a black background, or line drawings in black and white or color with black gloss, but there may be considerable variation in the level of detail, contrast, and use of color across the systems (von Tetzchner et al., 2024, ch. 1).

Communication partners can use AAC to make their own communication clearer, and AAC can function as communication support during conversation (Jonsson et al., 2011). People who are completely or partially speechless need AAC to make themselves understood and/or to understand others. People who use AAC form a complex group with great variation in cognitive and language development, ranging from those with little or no understanding of verbal language to those who understand but are unable to produce speech themselves.

3.2 People with SLCN in contact with the judicial system: A brief overview

People with SLCN may be vulnerable in multiple ways, and a growing body of international research indicates that a disproportionate number of them encounter the judicial system (Winstanley et al., 2018). SLCN puts people at an increased risk of becoming the victim of crime and abuse (Bornman et al., 2011). For instance, Brownlie et al. (2007) found that women with language impairment were more likely than women without impaired language to report sexual assault. Moreover, Nelson Bryen et al. (2003) found that, in a sample of 40 people who used AAC, almost half of them had experienced crime or abuse; most of them knew their perpetrator, but only one in four had reported their experiences to the police. A recent scoping review by Tan et al. (2024) provides evidence that children with SLCN are more likely to experience sexual abuse, maltreatment and domestic violence, and that adults with SLCN are at an increased risk of intimate partner violence.

In Norway, violence against people with disabilities is a significant problem (Gundersen & Vislie, 2019). Several national survey studies show that children, adolescents and adults with disabilities are more frequently exposed to violence than peers without disabilities (Bjørnshagen et al., 2024; Frøyland et al., 2023; Hafstad & Augusti, 2019). No Norwegian data are available on the prevalence of violence and abuse against people with SLCN specifically, and there is very limited research-based knowledge about their encounters and experiences with the legal justice system. However, it is generally considered that there is an underrepresentation of cases involving people with disabilities/SLCN in the Norwegian legal system. For instance, Søndenaa et al. (2019) found that 68% of a sample of 388 professional actors within the Norwegian police, court system and state prosecuting authorities reported having contact with people with cognitive disabilities once a year or less. This may indicate that disabilities often remain undetected and/or that cases involving people with disabilities remain unreported or do not get investigated.

The high prevalence of violence and abuse against people with SLCN makes them more likely to get in contact with legal services. Yet, they face significant barriers when accessing the criminal justice system, such as difficulties understanding the complex legal system and its language, and difficulties with testifying and giving evidence in an articulate manner (White et al., 2021). This includes challenges with presenting a coherent narrative to tell “their side of the story,” asking for help when they do not understand, and comprehending common legal terms. These difficulties may result in disengagement with the legal process. Poor linguistic competence and minimal responses may also lead to a negative perception by law enforcement officers, as their communication difficulties may be mistakenly interpreted as rudeness or non-compliance (Snow & Powell, 2011). Moreover, people with atypical communication patterns may encounter testimonial injustice when prejudice and bias among law enforcement officers undermine their credibility (Williams & Jobe, 2024). These factors may negatively influence a person’s passage through the legal justice system.

While Norwegian research concerning police officers’ experiences regarding investigative interviewing of people with SLCN is rare, several international studies have identified a need for more competence about SLCN among law enforcement officers. In a survey study with 98 South-African police officers, nearly all of them expressed a need for training related to disabilities, and participants identified training needs in, among others, sign language and communication skills (Viljoen et al., 2021). However, even when people self-disclose their SLCN, the information that they provide about their support needs may be ignored or their needs may remain unmet (Gormley & Watson, 2021). Thus, law enforcement officers need not only be able to recognize SLCN when they see it, they also need knowledge about how to accommodate and provide support for people with SLCN.

4. Police interviewing of children and particularly vulnerable adults in Norway

In Norway, children and particularly vulnerable adults who may have witnessed or become the victim of sexual assault, violence or other offenses, are invited to give a statement in a facilitated environment as an alternative to providing testimony in court. In this context, “particularly vulnerable adults” refers to people with intellectual and/or other disabilities who are in need of individualized support during police interviews (Ministry of Justice and Public Security, 2015). The facilitated investigative interview is tailored to the individual’s needs. It is usually conducted at Statens barnehus, where different services, such as child welfare services, police, medical services, etc., are gathered in one place, in order to minimize the burden on the child or vulnerable adult. The facilitated interview is audio- and video-recorded, and this recording is transmitted to a separate room, where a team of police, attorneys, counselors from Statens barnehus, and a safety person of the witness/victim are following the interview (Statens barnehus, 2025). During regular breaks, the police officer taking the interview discusses interviewing strategies with this team in order to conduct the interview as best as possible. In the event of a trial, the recorded interview can be played in court (Ministry of Justice and Public Security, 2015).

4.1 Facilitated investigative interviewing and sequential interviewing

Police officers who conduct facilitated investigative interviews in Norway are required to have completed an advanced training course in facilitated interviewing of children and adolescents from the Norwegian Police University College (Ministry of Justice and Public Security, 2015). This is a 15-credit course that consists of two components, namely child development (including communication with children and consequences of violence and trauma) and police-related subjects (including laws and regulations, interviewing techniques, and witness psychology). After completing the course, police officers should be able to plan and conduct facilitated interviews with children and collaborate with Statens barnehus.

Additionally, police officers are recommended to have completed an advanced training course of 15 credits in facilitated interviewing of children younger than six years of age and of particularly vulnerable adults (Ministry of Justice and Public Security, 2015). Facilitated interviews for young children and particularly vulnerable adults are often conducted as a series of shorter interviews, and they are therefore referred to as sequential interviews. This advanced training course enables police officers to conduct high-quality police interviews, in which both legal and ethical aspects of the job are carefully considered, while at the same time safeguarding the vulnerability of the witness or victim.

4.2 Advanced training course on facilitated interviews with the use of AAC

During the spring of 2025, a group of eight highly skilled police investigators who conduct facilitated interviews with children and/or particularly vulnerable adults followed a pilot course on the use of AAC during facilitated investigative interviews. The training course was initiated by the Northern Norway Regional Health Authority and the National Criminal Investigation Service (Kripos). This initiative arose as a response to an unmet need in Norwegian society, namely that people with SLCN are frequently denied their legal rights when they become the victims of sexual violence or other criminal acts, as they are commonly considered not capable of participating in an investigative interview.

Participants in the course were purposefully selected police officers from eight police districts who i) had already completed an advanced training course in facilitated investigative interviewing, and ii) had substantial experience with facilitated investigative interviewing of particularly vulnerable people.

In addition to the eight police officers, eight counselors from Statens barnehus that collaborate closely with the selected police officers also participated in the course. These counselors do not have formal education in law or policing, but do have expertise within psychology and communication and can advise police officers on communication strategies that may facilitate the police interview. However, their competence on the use of AAC is often limited. By inviting them to participate in the course, the course organizers aimed to ensure a shared knowledge base for police investigators and counselors.

The duration of the course was three plus two days, with participants completing tasks between the first and second parts of the course. The contents of the course included an introduction to AAC and its users, information about who might benefit from AAC within the context of a police interview, exploring an online database with pictures that can aid communication (www.bildstod.se ), observing and discussing parts of AAC-facilitated investigative interviews, a presentation by a prosecuting attorney about a court case that involved an AAC user, and an introduction to Talking Mats (i.e., a particular type of AAC that supports people with SLCN to express their feelings and views). The tasks between the first and second sessions consisted of conducting a Talking Mats conversation and preparing and conducting a police interview with the use of AAC, if possible.

5. Methodology

5.1 Research design

In order to shed light on this study’s research questions, focus-group interviews were used. A focus-group interview is a group discussion about a predefined topic, moderated by the researcher. The researcher uses a set of interview questions to engage the participants and guide the discussion, but participants can steer the conversation relatively freely with limited disruption from the researcher (Jordhus-Lier, 2023, p. 24). The dynamics of the group interaction can lead to lively discussions between research participants, which can generate rich, in-depth data (Gill & Baillie, 2018). Optimally, research participants explore areas of agreement and disagreement as they reflect together about the research topic.

For this study, the interview questions for the focus-group interviews centered around the following themes: challenges with conducting facilitated interviews with AAC, giving voice to people with SLCN, personal experiences with interviewing people with SLCN, AAC interviews as evidence in court, police officers’ training needs, and thoughts regarding the course that they had participated in. Participants were shown several questions on a screen in the room where the interviews were conducted, and they were asked to respond freely to these questions. Examples of questions are: “What do you consider to be the main challenges with conducting AAC-facilitated interviews?”, “What are your personal experiences with such interviews?”, “How can the interviewer secure a free account of people with SLCN?”, “Is it worth conducting AAC-facilitated interviews?”, “How do you know when to finish an interview?”, and “What did you learn from the course?”

The first author conducted the focus-group interviews in May 2025 at the course location in southeastern Norway. Both focus groups consisted of four participants, and each interview lasted 1 hour 42 minutes. Interviews were audio-recorded with Nettskjema diktafon, a secure dictaphone application for mobile devices, and transcribed verbatim by the first author.

Since all participants had become familiar with each other during the five-day training course, it was possible for the researcher to remain in the background during the focus-group discussions so that participants could discuss the interview questions as freely as possible. The atmosphere during the focus-group interviews could be described as safe and supportive; participants shared personal experiences and doubts, they felt comfortable enough to disagree with each other, and they expressed gratitude for having an arena for professional discussion.

5.2 Sample and recruitment procedure

The sample in this study consisted of eight experienced police officers (all female) that were hand-picked to participate in the advanced training course because of their long-standing experience with facilitated investigative interviewing. While they had substantial experience of interviewing children and adults with SLCN, most of them were not familiar with AAC at the outset of the course. Participants’ ages ranged from 40 to 55 (M= 50.6), and they had been working in the police for 15 to 34 years (M=27.4). Their experience with facilitated interviewing of children and adolescents ranged from 10 to 27 years (M=19.6), and their experience with sequential interviewing of young children under age six and particularly vulnerable adults ranged from seven to ten years (M=8.5).

At the beginning of the course, participants were informed about the research project and they were invited to participate. All participants were informed that participation was voluntary and that accepting or declining participation would not affect them in any way.

Because of this study’s focus on police officers’ perspectives, counselors from Statens barnehus that participated in the course were not invited to take part in the research interviews.

5.3 Data analysis

Interview data were analyzed using Braun and Clarke (2019) reflexive thematic analysis (RTA). RTA implies an exploratory and iterative coding process in which researchers engage with the data to produce themes and subthemes that are at the intersection of the collected data and the researchers’ theoretical assumptions and analytic skills. Through frequent reading of the interview transcripts and active engagement with the data to generate codes, themes and subthemes were constructed. These themes and subthemes were then reviewed to result in a meaningful interpretation of the data. This process led to four themes that together illustrate the study’s research questions: i) The need to anchor AAC in the entire legal system; ii) Giving a voice to people with SLCN; iii) Practical challenges with finding appropriate graphic symbols; and iv) Support needs for becoming skilled AAC interviewers.

5.4 Ethical considerations

The research study was reported to the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (ref.nr. 743092), which found that the project adhered to the guidelines for general data protection and ethical research. Participants were notified of the purpose and the methodology of the study during the first course day, and they were informed about what participation would require of them. They received information about the safeguarding of their anonymity and data management in the study, and they were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Immediately before starting the focus-group discussions, they were once more informed that participation was voluntary. All eight police officers that participated in the course welcomed the idea of research being conducted on this topic, and they all agreed to participate in the research study. The interviewer was not involved in the delivery of the course, and therefore it can be assumed that participants felt free to share their opinions and impressions regarding the course frankly.

Given the specificity of the course and the limited number of participants, safeguarding anonymity required special measures. First, participants were given pseudonyms in the text. Second, while background information such as age, number of years in the police force, and number of years of experience with conducting facilitated interviews was collected for each participant prior to the interviews, the authors decided against including such detailed information in the article. To guarantee that statements could not be traced back to single identifiable participants, this information is only presented as range and mean.

6. Results and discussion

In this section, we will now present the four themes that were identified in the data and illustrate them with interview excerpts. Furthermore, we will contextualize each theme within the existing knowledge base and discuss possible implications of our findings. The first and second themes illustrate the challenges and potential of AAC-facilitated investigative interviews at an overarching level, whereas the third and fourth themes describe more specific challenges and suggestions that were identified by participants.

6.1 The need to anchor AAC in the legal system

Participants in our study felt generally supported by colleagues and superiors at their local police office to conduct facilitated interviews. They experienced goodwill and an interest in professional development at their workplace, and their participation in the training course on AAC-facilitated interviews had been encouraged. Participants shared that whenever they requested more time to conduct a facilitated interview with a person with SLCN, this was rarely a problem. Yet, geographical differences did seem to occur, which might be traced back to varying knowledge and/or resources, as shown in the following excerpts:

Vilma: We have some interview leaders who are either impatient, don’t understand, are not in on it, and then it’s like: there you go (…) Then it happens that you get pushed to do this and that. I don’t let myself get pushed around, but yeah, it’s important to have a supportive team around you.

Beate: I often disagree with the interview leader about when to stop an interview.

While satisfied with the support that they received at their local police office, participants did express a need for increased competence about SLCN and support needs such as AAC for all actors in the legal system, in particular for legal professionals and court members. Participants were concerned that lawyers and judges lack insight into the communication needs of people with SLCN, and they expressed a desire for information and training for all professionals in the legal system. They believed that this could lead to a more widespread understanding and acceptance that AAC is a common language or even a mother tongue for many people with SLCN. Some of the participants stated the following:

Beate: What legal professionals want is that the victim first explains as much as possible without visual support, and then we can add visual support afterward, to try and lead the interview into more detail.

Grethe: It’s still the case that the court wants as many [spoken] words as possible.

During the interviews, it appeared that participants struggled with weighing two opposing considerations. On the one hand, they desired to secure a statement that is admissible in court, i.e., a statement that is given freely and orally. On the other hand, they wished to facilitate communication during the interview so that the person with SLCN could tell their story. To participants, this could seem like two equally important demands on a collision course. Consequently, there was some disagreement in the focus groups about when to use AAC, especially if the interviewee had some verbal language. Some participants were in favor of saving AAC as a back-up rather than using it from the start of the interview. They expressed concern that the use of AAC might be considered as bias in the interview, which could affect its value as evidence in court. Other participants felt that withholding AAC would make communication during the police interview unnecessarily hard for the person with SLCN. The court’s requirements about evidence standards were clearly reflected in participants’ reasoning about when and when not to use AAC:

Grethe: If we think of the interview with X [a minimally verbal adolescent with intellectual disability who spoke in one- and two-word sentences only], we got a lot of information orally that became very useful in court, without lining up visual support from the start.

Madelene: What we saw yesterday …. He did have some language, and then maybe it became a bit much with all those graphic symbols that were used, right? So, if we can hold those back, at least, but have them available.

Laila: Yeah, because nobody here would start the interview with using AAC?

Madelene: I wouldn’t, no.

Laila: But I find that kind of difficult, in a way. When shall we …?

This interview fragment illustrates the different objectives that police officers must balance. Several research studies have previously highlighted the inaccessibility of the legal system for people with SLCN (see, e.g., White et al., 2021), and the availability of AAC could in part alleviate this situation. Yet, limited research attention has so far been given to how the use of AAC may affect a person’s statement, how AAC-supported statements can meet the high standard of proof, and how courts will consider such statements as evidence. It is likely that this gap in the research base is closely related to the fact that very few cases concerning AAC users are investigated and tried in court (Bornman & Bornman, 2024). However, as findings from this study show, it is pivotal for law enforcement officials to work together and establish a common understanding of the AAC needs of people with SLCN. This may bring much needed clarification for police officers who are to conduct AAC-facilitated interviews.

6.2 Giving a voice to people with SLCN

Despite participants’ questions and doubts whether AAC-facilitated interviews of people with SLCN would be accepted as evidence in court, they were nonetheless highly motivated for the task. They used words like rewarding, exciting, demanding, and extreme sport to describe these interviews, suggesting a sense of meaningfulness and a feeling of doing something extraordinary. Moreover, participants were preoccupied with providing people with SLCN with a tool to express themselves and to give them a voice in the legal system, and to meet vulnerable victims with respect and listen to them. As one participant explained:

Beate: [AAC] gives more possibilities when it comes to legal justice. They [people with SLCN] get a chance to give their statement in their own way, and we help them with that. It’s a new world for us. We take care of those who need to be taken care of. That feels very good to me.

Participants knew cases concerning people with SLCN rarely make it to court (see, e.g., Bornman & Bornman, 2024), but a court trial and possible conviction was not their most important motivation. Instead, the main impetus seemed to be giving people the chance to relate what had happened to them:

Madelene: Often when you interview someone … the most important thing for them is really to come and talk to the police, and to get the help they need to tell what they want to tell. And then it is maybe not so important for them personally how it goes in court. Legal justice is important, but when you get to court, the evidence standards are so high. But maybe the work that we do is the most important to them. That they can tell what they have to say.

Laila: That’s what we comfort ourselves with.

Madelene: Yes, but to me it’s like that, that’s a fact. Because the evidence standards are so high, especially when we get to the next stage, the demands are so high, and it needs to be like that.

On the one hand, this interview fragment illustrates a certain sense of frustration about the challenges with getting such cases tried in court. On the other hand, it also clearly demonstrates participants’ belief in the value of being given the opportunity to provide a statement and to share one’s side of the story. This importance of being heard and believed when reporting a possible criminal action is also highlighted in other studies. For instance, a study by Rudolfsson (2023) emphasizes the need for victims to feel safe, understood, and respected during police interviews. Similarly, a study by McQueen et al. (2021) describes the importance of being believed when reporting sexual assault. Hence, participants’ strong motivation for giving a voice to people with SLCN when they have become the victim of crime is well-founded, and the use of AAC may facilitate this. Nonetheless, the difficulties with seeing such cases to court remain a major challenge to legal justice.

However, this challenge did not deter participants from doing their work with commitment and enthusiasm, since they frequently experienced that the police interviews led to positive consequences for victims:

Vilma: It’s never a waste of time. (…) Some of them may get further follow-up, they can get a new place to live, things can get fixed. (…) A lot of good things can happen.

Madelene: Just for them to be able to get to Barnehuset, and to meet a counselor who knows about the whole system. Because some of those we meet, they do not get any help from the social services, healthcare, etc. (…) They can get a completely new life, just by coming to the police, regardless of whether the case gets tried in court or not.

Thus, participants in this study seemed highly motivated by altruism and a genuine desire to improve the situation of vulnerable people who may have become the victim of crime. They acknowledged challenges with legal justice and with getting cases tried in court for people who use AAC, but they expressed a profound belief in the value of conducting police interviews with them regardless of these challenges, because of the multiple other positive outcomes that could occur.

6.3 Practical challenges with finding appropriate graphic symbols

While participants in our study were generally positive and recognized the benefits of using visual support and graphic symbols during communication with people with SLCN, they also identified a number of practical challenges related to the use of AAC during facilitated interviews. One of their main concerns related to selecting appropriate graphic symbols to be used during the interviews. Participants discussed difficulties with finding symbols that could illustrate actions and abstract or subjective concepts that were common to talk about during investigative interviews:

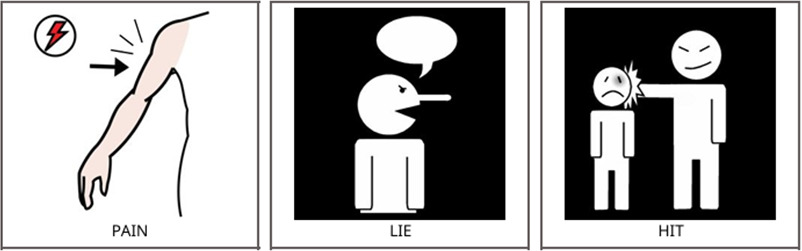

Katrine: I’m thinking of this symbol that illustrates pain, where you have a red dot on an arm, and a lightning bolt. I don’t feel that that would do the trick if we’re talking about pain in another body part. Then that symbol wouldn’t work. And the one about telling lies and telling the truth? I don’t feel that these symbols are any good. Because not everyone knows the story of Pinocchio. They wouldn’t necessarily know what it means.

Line: Yes, indeed. Images of verbs, actions, I find those hard. Nouns, specific things can be easier. But to find good symbols for actions and verbs …. For instance, the symbol for “to hit”, and then it’s showing stars. That’s kind of ….

The graphic symbols that participants refer to can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example images for abstract concepts and verbs. Retrieved from www.bildstod.se

The challenge the participants described is a known limitation of graphic communication systems, as they are typically dominated by nouns and to a lesser degree by verbs, and not all words are automatic “picture producers” (Bornman & Bornman, 2024). Hence, participants questioned whether available symbols for actions and subjective experiences would be easily understood by people with SLCN, especially if they had additional cognitive challenges that could make visual comprehension difficult. For instance, people with intellectual disability may have difficulties with perceptual reasoning and interpreting abstract images (World Health Organization, 2025), and this may affect their understanding of graphic symbols. Similarly, people with autism spectrum disorder may show atypical perceptual functioning (Bled et al., 2024), and sensory particularities may lead to difficulties with generalizing visual information from stylized symbols to real-life situations. Participants in our study wondered whether some people with autism could reject certain graphic symbols (e.g., a black-and-white image of a prototypical car), when these do not exactly reflect the real-life experience (e.g., a green Volvo 240), and they expressed concern about how this could affect the police interview. In a worst-case scenario, participants feared that the occurrence of a certain criminal act could be denied by a victim if the chosen symbols did not adequately represent what had happened. In this context, participants also discussed skin color used in the graphic symbols, which could differ from actual skin color, and they questioned whether this could cause confusion for some:

Vilma: I was thinking of those new symbols that we got, in which one person has fairer skin and the other one has darker skin. How wrong that could be, for instance for a person with autism. “Yes, but he doesn’t have dark skin, so that’s not right”.

Madelene: No, then it’s not right. “Did this happen?” “No!”. That makes it extremely difficult and vulnerable. And if you present an image that is wrong, where does the interview go from there?

Von Tetzchner et al. (2024, ch. 1) emphasize that graphic communication symbols are intended to have the same function as spoken words, and that a particular image within a graphic communication system usually depicts one instance of the category represented by the symbol. However, research is inconsistent as to whether people with autism manage such generalization adequately. A study by Hartley and Allen (2014) indicates that children with autism may have a poor understanding of the social-communicative function of pictorial symbols, making it harder for them to comprehend that pictures are intended as symbols for real-world entities. Yet, Wainwright et al. (2020) did not find such challenges with symbolic understanding in their sample of participants with autism. These contradictory findings may be the result of considerable variation in nonverbal intelligence in people with autism, but they may also be traced back to different degrees of iconicity or realism in the graphic symbols that were used in the studies. These research findings indicate that our participants’ concerns may be justified, but assumptions about poor visual comprehension are not necessarily correct. This highlights the need for police investigators to obtain a reliable report of the person’s language and visual comprehension prior to the interview, preferably from significant people in the individual’s environment who are well-informed about the person’s cognitive functioning (von Tetzchner et al., 2024, ch. 4). Moreover, high levels of realism when selecting graphic symbols for investigative interviewing may be recommended for specific groups of people with SLCN.

Participants also discussed whether people with SLCN would automatically understand graphic symbols for sexual assault and violent crime, as such symbols typically do not form part of the daily vocabulary of most AAC users. This issue was already raised by Collier et al. (2006), who found that the majority of AAC users have no way of communicating about sexuality and abuse. In the context of the current study, participants expressed concern about how the use of unfamiliar graphic symbols could possibly introduce new elements in a victim’s statement, thereby affecting the evidence in a case:

Katrine: This is something that I’ve been thinking about, like how to use these pictures, so that you don’t introduce something [in their statement] that doesn’t come from them (…). That you don’t use pictures that bring in elements that are not part of their story, something that doesn’t belong there or that could cause confusion. So, you need to be very, very careful about what you actually present to them and why and when.

Participants went on to discuss how the use of AAC could potentially lead the interview in a certain direction by “putting words in the person’s mouth” through the use of graphic symbols. They highlighted the risk of damaging a witness statement if symbols were presented at the wrong moment, or if the wrong symbols were being used. Furthermore, participants emphasized that, even with adequate graphic symbols available, it should not be taken for granted that these would automatically help the police interview. In certain cases, participants claimed, victims of sexual assault might not be aware of what the assault looked like and how the other person was positioned (e.g., if it occurred in a dark room or if the assault happened from behind), and therefore, they may not recognize a graphic presentation of it.

Additionally, participants identified an ethical issue with the use of graphic symbols for sexual assault, and they questioned the emotional impact of presenting explicit symbols to children and particularly vulnerable adults:

Laila: Often, they are not familiar with symbols that deal with the body and sex and all those things, because they do not teach those things to vulnerable kids at school …. Shall we then introduce them to something that they don’t know, right? One thing is the symbols that they do use, but another thing is that we show them loads of symbols for genitals.

Madelene: Yes, and how do they feel about that?

Grethe: Penetration and stuff. We need to consider the ethics of it.

Madelene: Yes, there’s some ethical issue there. How do they feel when police officers sit there and show them things that they find offensive or uncomfortable?

In sum, participants had several concerns and they identified limitations when it came to the use of graphic symbols during investigative interviews, ranging from uncertainty about visual comprehension to a lack of vocabulary for violence and abuse, to ethical issues when presenting explicit visual materials to children and vulnerable people. Nonetheless, participants seemed generally positive toward using AAC, but they felt in need of more competence and specific guidance for which graphic symbols to use when.

6.4 Support needs to become skilled AAC interviewers

At the time of the focus-group interviews, participants in this study had just completed a five-day advanced training course in facilitated police interviewing with the use of AAC, and they recognized that they were all at the starting point of a new practice. Their immediate responses after the course ranged from confusion: “I don’t feel like I’m any smarter now …” (Madelene), to cautious optimism: “It’s maybe not as difficult as I first thought” (Susanne). Participants were aware that they needed to get more experience with conducting facilitated interviews with people with SLCN, so that they could gain more expertise. However, they did already identify several support needs that could help them develop their competence further. One of the main suggestions was the development of a national database of graphic symbols, from which police officers could select the symbols that they needed when preparing for an interview. Participants considered this could be useful, as they found it time-consuming to find appropriate symbols. They also stated that a common database could improve the quality of the graphic symbols that are being used, which would make them more confident in their choice of symbols. At the same time, they were aware that the same symbols could not be used in every case, and that it is necessary to use individually tailored AAC depending on whom they meet:

Line: There’s no fixed formula to follow.

Laila: We need to accommodate the person who will be interviewed, so we cannot use the same template for everyone, or the same symbols. We need to …

Line: … to tailor it to the person that we’ve got in front of us.

This excerpt illustrates participants’ understanding of the diverse needs of people with SLCN, while at the same time highlighting the need for access to materials that could make such support more readily available. This idea was also suggested by White et al. (2015), who recommended developing an AAC resource toolkit to assist the legal justice system when people with SLCN are to testify in court. Such a toolkit or database could help police officers when preparing and conducting facilitated interviews, and it might contribute to a more accessible legal system throughout the country.

Another suggestion for further development concerned the need for a discussion forum where police officers could share experiences and learn from each other. Participants also expressed a wish to see more video recordings of facilitated interviews with AAC, so that they could become more familiar with the practice. Furthermore, participants expressed the need to provide training courses for law enforcement officials at all stages of the legal system, so that knowledge about people with SLCN and the use of AAC would become more common:

Susanne: I feel that legal professionals who work in this field know too little about this, especially the ones that work with sexual assault. They are in fact competent prosecuting attorneys, but they’re not here [at the course]. I feel that they should have been here and learned loads about this.

Thus, participants felt that information about SLCN and AAC for all legal professionals could contribute to making facilitated interviews with AAC an established legal practice.

Table 1 summarizes the learning objectives of the advanced training course that study participants completed, as well as the further needs for competence building that they identified during the focus-group interviews. This information may be useful for other researchers and legal actors worldwide when considering the question of how to make the criminal justice system more accessible for people with SLCN.

Table 1.

Learning objectives in the advanced training course | Further needs for competence building |

|---|---|

Obtain basic knowledge about SLCN and AAC. | Develop a database of graphic symbols for use during police interviews. |

Be able to identify who may benefit from AAC within the context of a police interview. | Establish a national network for sharing experiences, discussion and reflection about facilitated interviews with AAC. |

Become familiar with an online database for graphic symbols. | Watch video recordings of facilitated police interviews with AAC to gain more insight. |

Watch and critically analyze facilitated interviews in which AAC is used. | Share knowledge about SLCN and AAC throughout the criminal justice system. |

Be able to conduct a Talking Mats conversation. | |

Understand the main challenges that AAC may pose in the legal systems |

The main objective of this study was to explore the potential and challenges that Norwegian police officers see in using AAC-facilitated interviews for people with SLCN. In sum, findings indicate that participants were positive about using AAC. They underscored the value of giving a voice to people who have become the victim of crime but who struggle with giving a verbal statement. At the same time, participants highlighted the need to share information about SLCN and AAC throughout the criminal justice system in order to create understanding and acceptance for the use of AAC during investigative interviews. Moreover, participants offered specific suggestions for how they could develop their competence even further. These suggestions, in combination with the learning objectives of the course, may provide useful information and direction to other nations that have ratified the UN CRPD and that want to improve access to justice for people with SLCN.

7. Limitations

The main limitation of this study is that participants were interviewed immediately after they had completed the second part of the advanced training course. Consequently, most of them had not yet gained substantial experience with conducting investigative interviews with the use of AAC. This means that some of the participants’ thoughts and reflections concern hypothetical issues, while others are based on direct experience. The practice of interviewing people with SLCN by means of AAC is innovative and ground-breaking, and therefore, further research is warranted. Future research may uncover new challenges and opportunities that participants at the time of the interviews were not yet aware of. Thus, findings in this study should be interpreted with caution.

8. Conclusion

Even though people with SLCN are at an elevated risk of becoming the victims of violence and sexual assault, very few countries in the world have a practice of offering facilitated police interviews with the use of AAC. This lack of communication support contributes to making the criminal justice system inaccessible for them. Therefore, the United Nations (2006) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities obliges States Parties to promote appropriate training for those working in law enforcement, so that disability may be identified and support can be provided. Despite this obligation, few evidence-based programs are available to support law enforcement officials in their contacts with people with SLCN.

The current study was conducted in connection with the piloting of an advanced training course in facilitated interviewing with AAC. Its findings contribute to the research field with police officers’ reflections concerning AAC-facilitated interviews. Main findings show that the practice of investigative interviewing with AAC needs to be anchored in the entire criminal justice system to ensure that the rationale behind such interviews is understood. Study participants showed great motivation for giving people with SLCN a voice in the legal system, and they identified strategies that could help them develop their competence further. Some practical challenges regarding the use of graphical images were also discussed. Future research should investigate how AAC-facilitated interviews are conducted, how evidence obtained through such interviews is weighed in court, and how people with SLCN experience their contact with the police when AAC is used during communication. Given the high prevalence of SLCN among suspects and offenders, the use of AAC should also be considered for them to secure their passage through the criminal justice system.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Northern Norway Regional Health Authority for funding the advanced training course and the accompanying research study.

References

-

Baggio, S.,Fructuoso, A.,Guimaraes, M.,Fois, E.,Golay, D.,Heller, P.,Perroud, N.,Aubry, C.,Young, S.,Delessert, D.,Gétaz, L.,Tran, N.T.&Wolff, H. (2018). Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in detention settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Frontiers in Psychiatry

, 9 , 331. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00331 -

Bercow, J. (2008). The Bercow Report: a review of services for children and young people (0-19) with speech, language and communication needs. Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF).

Digital Education Resource Archive (DERA)

. -

Beukelman, D.R.&Light, J.C. (2020).

Augmentative and alternative communication. Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs

. (5th ed).Paul Brookes Publishing Co

. -

Bishop, D.V.M.,Snowling, M.J.,Thompson, P.A.&Greenhalgh, T. (2017). Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology.

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry

, 58 , 1068–1080. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12721 -

Bjørnshagen, V.,Olsen, T.,Vedeler, J.S.&Eriksen, J. (2024).

Hatytringer, hatkriminalitet og diskriminering – funksjonshemmedes erfaringer [Hateful comments, hate crime, and discrimination – Experiences of people with disabilities]

.Fafo-report 2024:19

. -

Bled, C.,Guillon, Q.,Mottron, L.,Soulieres, I.&Bouvet, L. (2024). Visual mental imagery abilities in autism.

Autism Research

, 17 (10), 2064–2078. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.3192 -

Bornman, J.&Bornman, H.G. (2024). Augmentative and alternative communication in the South African justice system: Potential and pitfalls.

South African Journal on Human Rights

, 39 (4), 301–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/02587203.2024.2356537 -

Bornman, J.,Nelson Bryen, D.,Kershaw, P.&Ledwaba, G. (2011). Reducing the risk of being a victim of crime in South Africa: you can tell and be heard!.

Augmentative and Alternative Communication

, 27 (2), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2011.566696 -

Braun, V.&Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis.

Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health

, 11 (4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806 -

Brownlie, E.B.,Jabbar, A.,Beitchman, J.,Vida, R.&Atkinson, L. (2007). Language impairment and sexual assault of girls and women: Findings from a community sample.

Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology

, 35 (4), 618–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9117-4 -

Byram, L. (2022). Disability accessibility in Washington courts.

Interdisciplinary Journal of Student Research and Scholarship

, 6 (1). https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/access/vol6/iss1/4 -

Coles, H.,Gillett, K.,Murray, G.&Turner, K. (2017).

Justice evidence base

.The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists

. -

Collier, B.,McGhie-Richmond, D.,Odette, F.&Pyne, J. (2006). Reducing the risk of sexual abuse for people who use augmentative and alternative communication.

Augmentative and alternative communication

, 22 (1), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434610500387490 -

Diamond, L.L.&Hogue, L.B. (2023). Law enforcement officers: A call for training and awareness of disabilities.

Journal of Disability Policy Studies

, 33 (4), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/10442073221094803 -

Edwards, C.,Harold, G.&Kilcommins, S. (2015). “Show me a justice system that’s open, transparent, accessible and inclusive”: Barriers to access in the criminal justice system for people with disabilities as victims of crime.

Irish Journal of Legal Studies

, 5 (1). https://hdl.handle.net/10344/4575 -

Frøyland, L.R.,Lid, S.,Schwencke, E.O.&Stefansen, K. (2023).

Vold og overgrep mot barn og unge. Omfang og utviklingstrekk 2007–2023 [Violence and abuse against children and adolescents. Prevalence and developments 2007–2023]

.Velferdsforskningsinstituttet NOVA

. -

Geijsen, K.,Kop, N.&de Ruiter, C. (2018). Screening for intellectual disability in Dutch police suspects.

Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling

, 15 (2), 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1502 -

Gill, P.&Baillie, J. (2018). Interviews and focus groups in qualitative research: An update for the digital age.

British Dental Journal

, 225 (7), 668–672. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.815 -

Gormley, C.&Watson, N. (2021). Inaccessible justice: Exploring the barriers to justice and fairness for disabled people accused of a crime.

The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice

, 60 (4), 493–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/hojo.12433 -

Gulati, G.,Cusack, A.,Kelly, B.D.,Kilcommins, S.&Dunne, C.P. (2020). Experiences of people with intellectual disabilities encountering law enforcement officials as the suspects of crime – A narrative systematic review.

International Journal of Law and Psychiatry

, 71 , 101609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2020.101609 -

Gundersen, T.&Vislie, C. (2019). Voldsutsatte med funksjonsnedsettelser – individuelle og strukturelle barrierer mot å søke hjelp [Victims of violence with disabilities – individual and structural barriers for seeking helt]. InK. Skjørten,E. Bakketeig,M. Bjørnholt&S. Mossige(eds.),

Vold i nære relasjoner. Forståelser, konsekvenser og tiltak [Violence in close relationships. Understandings, consequences, and interventions], ch. 9

.Universitetsforlaget

. https://doi.org/10.18261/9788215032320-2019 -

Hafstad, G.S.&Augusti, E.M. (2019).

Ungdoms erfaringer med vold og overgrep i oppveksten: En nasjonal undersøkelse av ungdom i alderen 12 til 16 år [National survey on child abuse and neglect among a representative sample of Norwegian 12–16-year-olds]

.Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter om vold og traumatisk stress [Norwegian Centre for Traumatic Stress Studies]

. -

Hartley, C.&Allen, M.L. (2014). Intentions vs. resemblance: Understanding pictures in typical development and autism.

Cognition

, 131 (1), 44–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2013.12.009 -

Jonsson, A.,Kristoffersson, L.,Ferm, U.&Thunberg, G. (2011). The ComAlong Communication Boards: Parents’ Use and Experiences of Aided Language Stimulation.

Augmentative and Alternative Communication

, 27 (2), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2011.580780 -

Jordhus-Lier, D. (2023).

Fokusgrupper som metode [Focus groups as a research method]

.Cappelen Damm Akademisk

. -

Kapa, L.L.&Plante, E. (2015). Executive function in SLI: Recent advances and future directions.

Current Developmental Disorders Reports

, 2 (3), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-015-0050-x -

LeVigne, M.&Van Rybroek, G. (2014). ‘He got in my face so I shot him’: How defendants’ language impairments impair attorney-client relationships.

City University New York Law Review

, 17 (1), 70–111. https://doi.org/10.31641/clr170103 -

McQueen, K.,Murphy-Oikonen, J.,Miller, A.&Chambers, L. (2021). Sexual assault: Women’s voices on the health impacts of not being believed by police.

BMC Women’s Health

, 21 (1), 217. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01358-6 -

Ministry of Justice and Public Security . (2015). Regulation on interviewing children and other particularly vulnerable victims and witnesses (facilitated interviews). https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2015-09-24-1098

-

Nelson Bryen, D.,Carey, A.&Frantz, B. (2003). Ending the silence: Adults who use augmentative communication and their experiences as victims of crimes.

Augmentative and Alternative Communication

, 19 (2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/0743461031000080265 -

Rudolfsson, L. (2023). “I want to be heard”: Rape victims’ encounters with Swedish police.

Violence Against Women

, 30 (12–13), 3163–3186. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012231176206 -

Snow, P.C.&Powell, M.B. (2011). Oral language competence in incarcerated young offenders: Links with offending severity.

International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology

, 13 (6), 480–489. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.578661 -

Statens barnehus . (2025). Statens barnehus. Who are we?.

Politiet & Statens barnehus

. https://www.statensbarnehus.no/media/1441/hvem-er-vi_engelsk.pdf -

Søndenaa, E.,Olsen, T.,Kermit, P.S.,Dahl, N.C.&Envik, R. (2019). Intellectual disabilities and offending behaviour: The awareness and concerns of the police, district attorneys and judges.

Journal of Intellectual Disabilities and Offending Behaviour

, 10 (2), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIDOB-04-2019-0007 -

Tan, C.Y.T.,Choo, A.L.,Lim, V.P.C.&Wilson, I.M. (2024). The relationship between speech and language disorders and violence against women: A scoping review.

Trauma, Violence, & Abuse

, 26 (5), 1027–1045. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380241299432 -

United Nations . (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf

-

United Nations . (2015).

Sustainable Development Goals

. https://sdgs.un.org/goals -

Viljoen, E.,Bornman, J.&Tönsing, K.M. (2021). Interacting with persons with disabilities: South African police officers’ knowledge, experience and perceived competence.

Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice

, 15 (2), 965–979. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paaa084 -

von Tetzchner, S.,Martinsen, H.&Stadskleiv, K. (2024).

Augmentative and alternative communication for children, adolescents and adults with developmental disorders

.Routledge

. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781003387633 -

Wainwright, B.R.,Allen, M.L.&Cain, K. (2020). The influence of labelling on symbolic understanding and dual representation in autism spectrum condition.

Autism & Developmental Language Impairments

, 5 . https://doi.org/10.1177/2396941520931728 -

White, R.,Bornman, J.&Johnson, E. (2015). Testifying in court as a victim of crime for persons with little or no functional speech: Vocabulary implications.

Child Abuse Research: A South African Journal

, 16 (1), 1–14. -

White, R.,Bornman, J.,Johnson, E.&Msipa, D. (2021). Court accommodations for persons with severe communication disabilities: A legal scoping review.

Psychology, Public Policy, and Law

, 27 (3), 399–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000289 -

Williams, H.&Jobe, A. (2024). Testimonial injustice: Exploring ‘credibility’ as a barrier to justice for people with learning disabilities/autism who report sexual violence.

Disability & Society

, 40 (4), 1061–1083. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2024.2323455 -

Winstanley, M.,Webb, R.T.&Conti‐Ramsden, G. (2018). More or less likely to offend? Young adults with a history of identified developmental language disorders.

International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders

, 53 (2), 256–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12339 -

World Health Organization . (2025).

International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision

.(ICD-11)

.

- 1The online database www.bildstod.se was developed by DART, a specialized center under Västra Götalandsregionen in Sweden, that is working with communication and communication aids for people with disabilities. The website is a freely accessible resource with graphic symbols to be used in communication and information materials. It provides AAC that can be useful in various contexts, such as healthcare, rehabilitation services, school and legal settings. The graphic symbols that can be found in the database come from different symbol systems, such as ARASAAC Symbol Set, Tawasol Symbols, Bliss, and Sclera symbols.