Intimate Partner Violence: Conflicts of Priority in Police Practice

PhD

Malmö Centre for Policing and Prevention, Malmö University, Sweden

nina.axnas@polisen.seProfessor

Department of Criminology, Faculty of Health and Society, Malmö University, Sweden

Publisert 19.12.2025, Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing 2025/2, Årgang 12, side 1-25

Lethal violence in intimate relationships is frequently preceded by less severe forms of abuse. In Sweden, the clearance rate for non-aggravated assault remains low, partly due to organisational goal conflicts within the police force. Consequently, the police face challenges in both resolving intimate partner violence (IPV) cases and preventing escalation into more serious violence. This study aims to advance understanding of the investigative process concerning IPV in Sweden and examine whether investigative measures differ depending on the relationship between victim and perpetrator – whether intimate, acquainted, or unfamiliar. The analysis draws on police investigations conducted in Stockholm between 2016 and 2021. Findings indicate that structural limitations, particularly victim non-cooperation, significantly constrain the investigation of non-aggravated IPV. This reluctance impacts the application of investigative measures and often leads to early case closures when prosecution appears unlikely. These results underscore the need for more effective strategies to enhance victim engagement and improve the overall investigative process in IPV cases.

Keywords

- Intimate partner violence ;

- IPV ;

- police investigation ;

- police practice ;

- conflicting demands ;

- goal conflict ;

- clearance rate

1. Introduction

The overall goal for the Swedish police, ever since New Public Management (NPM) was introduced, has been to increase the clearance rate of crimes (see, e.g., Regeringen, 2006; Regeringen, 2019). Goal achievement has been measured through statistics on reported crimes and cases submitted/referred to prosecutor (see, e.g., Polisen, 2007b, 2020). The police’s official statistics on domestic violence suggest that the goal has not been achieved (Polisen, 2022d). Between 2013 and 2023, the number of submitted/referred cases, also viewed as a measure of clearance rates by the police, concerning domestic assault has decreased by 25 per cent (Polisen, 2024c).

In recent years, two of the Swedish police’s most important goals have been to combat serious crimes, including organised crimes and shootings, as well as crimes against particularly vulnerable victims in close relationships (Polisen, 2019). A mapping made by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (Brottsförebyggande rådet, BRÅ) showed that between 2018 and 2023, the number of employees increased by 2,900 people (36%), but the staff growth was significantly lower at the local level compared to the district and regional levels (Franke Björkman & Fjelkegård, 2024). However, as both organised crimes and intimate partner violence (IPV) are handled at the local police level, the significant increase in staff has not adequately addressed the influx. As a result, most cases of assault within close relationships and that are not classified as serious receive lower priority (Franke Björkman & Fjelkegård, 2024). The study further showed that, while the case inflow for crimes against particularly vulnerable victims remained essentially unchanged between 2018 and 2023, the number of employees in specialised investigative units handling intimate partner violence (IPV) increased by 70 per cent (Franke Björkman & Fjelkegård, 2024). BRÅ thus assessed that the IPV units should have a good capacity to manage the inflow of cases involving particularly vulnerable victims. However, BRÅ could not find any support for an increase in the clearance rates. Furthermore, BRÅ noted that this may partly be due to the fact that the investigative teams for IPV are characterised by high absenteeism, with one-third consisting of staff who have been employed for less than a year, and therefore lack the experience necessary for the operation to function optimally (Franke Björkman & Fjelkegård, 2024).

Police resources are necessary to investigate crime, but the lack of an increase of the clearance rate could also be a natural consequence of non-optimal conditions for investigating non-serious violence (Axnäs, 2024). The problem is that the Swedish police do not regularly follow up on, or quality-assure, closed investigations. Thus, the Swedish police do not know the conditions under which the crime was investigated, nor do they know which investigative measures have been taken, as follow-up on investigative activities focuses on cases submitted to the prosecutor (Axnäs, 2024). An unwilling victim who does not cooperate, and/or a lack of witnesses or other supporting evidence, makes it difficult to disprove self-defence and to prove the intent to “inflict bodily harm, illness, or pain” in accordance with Chapter 3, Section 5 of the Penal Code (Axnäs, 2024). However, it may also be that the goal (to increase prosecution) and the chosen measurement method (more offenders being convicted) do not address the core issue: that the perpetrator should stop committing violence against their partner.

In light of this, the society in which the police are one actor needs to approach the issue from multiple perspectives rather than simply focusing on the idea that a conviction will stop someone from abusing. The police’s ongoing monitoring of investigative work needs to focus on what is not being done and why, rather than on the number of cases that lead to prosecution. This is particularly important because the number of convictions, especially prison sentences for minor and standard assault, is relatively low, and since the Swedish police must manage daily conflicting demands (Axnäs, 2024).

The core issue in this conflict of objectives is that the Police Act states that it is the police’s duty to investigate crimes but on the other hand, they are required to discontinue an investigation “if there is no longer any reason to continue the investigation” (RB 23:4), or “if further investigation would incur costs that are not proportionate to the importance of the matter, and it can also be assumed that the severity of the crime does not exceed a sentence of three months’ imprisonment” (RB 23:4 a). That means, if the investigation leader believes that it would be impossible to convict anyone for the crime – even if further investigative measures will be taken – they could and should close the file (Polisen, 2021b). At the same time, it is stated that the police shall ensure an effective capacity to prevent and investigate violence by men against women in intimate relationships (Regeringen, 2024).

This study focuses on “investigability” and the Swedish police’s capability to actually investigate and solve cases of non-aggravated assault – thereby meeting the expectations to combat domestic violence through increased prosecution. The analysis and discussion focus on the conflict of demands that the police face daily.

1.1 Previous research

Even though the Swedish police have, for several decades, been required to increase prosecutions in general and those for high-volume crimes specifically (see, e.g., Polisen, 2007b, 2010a, 2010b, 2013, Riksrevisionen, 2023), little or no focus has been placed on examining the actual conditions under which the Swedish police can influence crime resolution (Axnäs, 2024). Also, the number of international studies concerning decisions in the investigation of less serious crimes – so-called volume crimes or everyday crimes – is limited (Jansson, 2005). Overall, the investigative process has been underexplored (Axnäs, 2024; Horvath et al., 2001; Liederbach et al., 2011; Neyroud, 2011). Simultaneously, prior studies have demonstrated that deadly violence against women in intimate partnership is often preceded by earlier threats or warnings, e.g., reports about, or convictions for, less serious violence (Caman et al., 2017; Hansen & Møller Okholm, 2024; Hjertén & Rapp, 2023; Nilsson, 2002; Socialstyrelsen, 2024; Vatnar et al., 2022; Vatnar, 2015). For example, a study of all women in Sweden between 2018 and 2023 who were killed by a man with whom they currently (at time of death) or previously had an intimate relationship showed that 46 per cent of the perpetrators had previously been reported for violent crimes or threats (Hjertén & Rapp, 2023). Another study of intimate partner violence in Sweden showed that 53 per cent of the women who reported that they had been abused by their partner had earlier had offences committed against them (Nilsson, 2002). The proportion of perpetrators who have previously been convicted of violent crime when suspected of deadly violence is lower. A study by Caman et al., which examined the characteristics of perpetrators for intimate partner homicides in Sweden, showed that 26 per cent of the perpetrators had a history of convictions for violence (Caman et al., 2017), while the National Board of Social Security’s investigation into certain deaths showed that only 10 per cent were convicted of violent crime (Socialstyrelsen, 2024). Vatnar et al. (2022) state that even though lethal violence in intimate relationships has decreased over time in Norway between 1990 and 2020, lethal intimate partner violence is often the culmination of prolonged prior abuse. Risk assessments and coordinated interventions are therefore crucial to reducing lethal violence.

Since the 1970s, the studies conducted on police investigative work or the success factors for solving volume crimes have largely agreed that most cases investigated by the police come to their attention through the public. Cases initiated because of intelligence work and surveillance have been uncommon (Coupe, 2016; Coupe & Griffiths, 1996, 2000; Greenwood & Petersilia, 1975; Robinson & Tilley, 2009; Tilley et al., 2012). Investigative work is conducted reactively. Regarding identified success factors, the public is also the police’s primary ally: a witness being able to identify the perpetrator or provide a name and information leads to the perpetrator being identified (Jansson, 2005; Robinson & Tilley, 2009). Swedish studies that have examined success factors in solving crimes in close relationships show that strong evidence in the form of witnesses and documented injuries, as well as the suspect confessing and the victim not hesitating to participate in the police investigation, are circumstances that prosecutors want to see in order to press charges (Ekström & Lindström, 2015; Marklund & Nilsson, 2008). In parallel, one reason to close and file an investigation regarding assault in general is if the victim does not cooperate (Axnäs, 2024; Eksten, 2009).

Although the number of studies on police investigative processes is limited, a recently published study has in fact examined the conditions and capabilities for investigating non-aggravated assault offences more generally (Axnäs, 2024). The study indicates that what the police should and are permitted to do at the organisational level does not always correspond with what can be done and is done at the individual level (Axnäs, 2024). There are several investigative measures that should be taken when an assault occurs and is reported to the police (Polisen, 2022a). But most of the investigative measures are not possible to carry out if the victim does not cooperate (e.g., video documented interview with the victim, photo document injuries, authorisation to obtain a copy of the medical record). The logical consequence of this is that the victim’s willingness to cooperate (and the presence of witnesses) become the decisive factors that in a positive way influence the potential for a case to be investigated, since the police rationing and deprioritise cases where the victim does not cooperate (Axnäs, 2024).

This rationing has also been examined by Liljegren et al. (2021). They found that one strategy for handling a massive inflow of volume crimes (for example theft, vandalism, fraud, drug offences, minor violent crimes, etc.) is by putting cases on hold or “in balance”. In such cases, the outcome may be that further investigative measures are sometimes not carried out in time or at all, even though it would be possible and perhaps even necessary to create a sufficient basis for decision-making. This means that if the case is put on hold long enough, the investigation leader may close and file the case with a clear conscience. According to the study by Liljegren et al., which included both observations and interviews, one of the mechanisms for a case to be put on hold depends on its character (Liljegren et al., 2021). That conclusion was also confirmed by Axnäs (2024), who found that the most common reason why investigative measures that could have been taken were not taken was that the injuries were minor combined with the fact that the violence had been preceded by verbal arguing or included a counter-claim report from the suspect (Axnäs, 2024).

The conclusion from previous studies regarding the investigation process must be that the nature of cases – specifically, the extent to which there are witnesses and what the victims and witnesses are able or willing to share – likely influences the outcome of an investigation and, consequently, the police’s investigative results and possible prevention effect. Furthermore, it also seems that investigations in which the victim’s injuries are not severe or can be documented, tend to negatively affect the case resolution. This means that the decisions the police make – or are forced to make initially – such as whether to initiate an investigation and the selection of investigative measures undertaken – are likely to impact the extent to which potential witnesses are identified and interviewed.

2. Theoretical framework

The police make daily rational choices based on the information that is possible to collect, which aligns with March’s conception of rational decision theory (March, 1994). At the same time the police organisation can be described as one in which officers use their professional knowledge and discretion daily in their interactions with citizens (Lipsky, 2010). Therefore, rational decision theory (March, 1994) and Lipsky’s theory on how street-level bureaucracies manage and prioritise an ever-increasing flow of cases (Lipsky, 2010) will be used for analysing and addressing whether, why, and how the investigation process differs based on the severity of the crime, the nature of the case, and the characteristics of the parties involved.

A minimum requirement for understanding and analysing organisations is that the organisation’s mission and conditions are clearly defined (Freidson, 1988). In addition, the environment and the rules that the organisation must adhere to must also be identified, especially the profession’s approach to the organisation’s various preferences, which may, to varying degrees, be in direct conflict with one another (Brodkin, 2011; Jönsson, 2021). The duties of the police are specified and regulated by the Police Ordinance (2014:1104), the Police Act (1984:387), and the Code of Judicial Procedure (RB). However, the police also function as a street-level bureaucracy, transforming overarching criminal justice policy goals and ambitions into practical operations (Lipsky, 2010). Conflicts between the legislature’s normative goals and the political objectives of the organisation force or enable the decision maker to choose which preference should be given interpretative preference (Jönsson, 2021). The street-level bureaucrats can be both forced and allowed to prioritise cases to meet the organisation’s preference for “being effective” at the expense of the legislature’s intention that the police’s task is to “investigate crimes”, as the discretion is described by, for example, Lipsky (2010) and Liljegren et al. (2021).

On one hand, according to Lipsky, street-level bureaucracies are characterised by the fact that their officers are at the bottom of the organisational decision hierarchy, but at the same time, due to their profession, they have significant discretion and direct interaction with individuals (victim and offenders) seeking the organisation’s services (Lipsky, 2010). On the other hand, the individual police officer’s room for discretion is limited by laws, regulations, personal values, collegial factors, the actual leader who often lacks “proven experience”, and the organisational context (Jönsson, 2021). It is equally a matter of determining which cases may be deprioritised, with reference to the relevant legal provisions and grounded in rational decision-making (Liljegren et al., 2021). Fundamentally, it is a matter of normatively rule-bound and rational decisions about what the police should and are allowed to do when a crime is reported, as well as the available (rational) choices (Axnäs, 2024). Nonetheless, how individual officers interpret and relate to the rules and policies may vary.

3. Aims

The overall aim is to increase the knowledge about the role of the police in the investigation process for intimate partner violence and whether there are differences in how the police utilise investigative measures when the crime occurs in a close relationship compared with violence between acquaintances or strangers.

Two important questions will be examined and discussed.

-

What are the conditions for the police to investigate and solve IPV crimes when injuries are less severe?

-

Given the current circumstances, the conditions to investigate and the police’s ability, is it possible for the police to contribute to an increased prosecution rate?

4. Method and data

The study employs a mixed-methods approach. The quantitative component involves collecting police reports to identify what investigative measures can initially be taken and which have actually been implemented. To deepen understanding of the investigative process in practice – particularly why certain measures were not undertaken – qualitative, semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten investigation leaders. These interviews explored the criteria that inform decisions to close an investigation and how various circumstances are assessed. Based on their responses, several factors emerged that the investigators, either partially or unanimously, identified as reasons for terminating an investigation. These factors were also typical of cases that were generally difficult to establish as criminal offences and, consequently, seldom allowed for a reliable prediction of prosecution.

4.1 Interviews with investigation leaders

The interviewees (six women and four men) had at least five years of experience in being investigation leaders and more than 10 years as police officers. Four had more than 10 years of experience with investigation management. The majority had more than 20 years in the profession. They had experience of leading investigations at the police contact centre (PKC), the duty office, or at an investigation section in the police region of Stockholm between 2016 and 2021. It is conceivable that investigation leaders with several years of experience make the active choices between the legislature and the political goal easier, but also that they are more transparent with their behaviour in an interview.

By using an interview guide with open-ended questions, the interviews were expected to capture spontaneous responses and highlight both general perceptions (with which the majority agreed) and more specific ones (expressed by only one or a few). Based on the responses, it was possible to create variables that, with high reliability, are assumed to measure the investigation leaders’ rationing and prioritisation principles. The following questions were asked:

-

What circumstances are required in order to not initiate an investigation, even when there is reason to believe that a crime has been committed?

-

How do you interpret the concept that “the crime is impossible to investigate”?

-

In some cases, the victim is not interviewed, even though there are witnesses. How is this decision justified?

-

In some cases, witnesses are not interviewed, despite being identified. How is this justified?

-

Do you always have time to review the entire investigation file – including the report, notes, interviews, and logs – before deciding?

-

How common is the collection of DNA evidence and forensic certificates?

-

How do you handle a report where information about witnesses is missing? (Do you assume there are none, or do you contact the patrol?)

-

Are there specific types of cases or circumstances in which you always or never initiate an investigation?

-

A weak evidentiary basis can be a reason to close an investigation. Can it also be a reason to not initiate an investigation in the first place?

The overall conclusion from the investigation leaders’ responses to the interview questions identified three independent variables that represent aggravating circumstances. These are factors – aside from a lack of cooperation from the victim – that were believed to influence whether an investigation is not initiated or is discontinued. These circumstances include: the victim having no or only minor injuries; the presence of information about verbal arguments; and situations in which the suspect files a counter-claim and witnesses are absent. Quotes from the interviews are presented in the result section and in the discussion to exemplify how different aspects and choices during the investigative process can be perceived.

4.2 Data

The quantitative study consists of 287 randomly chosen police investigations regarding non-aggravated assault reported in Sweden, in the Stockholm Police Region (excluding Gotland) from 2016 to 2021, where both the victim and the identified suspect were 18 years or older. The conditions and capabilities for the investigation process for cases involving intimate partner violence (n=61) are compared with cases where the victim and the perpetrator are acquaintances (n=112) or strangers (n=114).

4.3 The variables

The dependent variable measures the result of the investigation process, i.e., whether the case was referred to the prosecutor or closed by being dismissed. Nine per cent (n=26) of the cases were referred to the prosecutor.

4.3.1 Ability and capability variables (investigative measures)

The investigative measures that should be undertaken are specified in policy documents. The independent variables that measure ability and capability are chosen from checklists and policy documents according to investigative measures (Polisen, 2016, 2021a, 2021b, 2023a). However, previous studies have shown that certain investigative measures are significantly positively correlated with case clearance (Axnäs, 2024). These include: interviewing the victim, offering and securing acceptance of a victim’s counsel, retrieving the victim’s medical records, interviewing witnesses, and obtaining CCTV footage. The five variables used to measure the police’s ability and capacity are generally coded as dummy variables, with the exception of the victim’s counsel variable. This variable is ordinal and can take three values: not offered (0), offered but not accepted (1), and offered and accepted (2).

4.3.2 Conditions-to-investigate variables

The condition-to-investigate variables are based on logical, deductive reasoning regarding the prerequisites for carrying out the investigative measures mentioned above. These include whether the victim cooperates with the police, whether the victim requires medical care, and whether there is information about witnesses or available CCTV footage. These variables are binary.

4.3.3 Conditions-to-solve variables

These variables measure the conditions necessary to solve and substantiate the crime, that is, what can actually be proven. They include factors such as whether the suspect confesses, what witnesses have observed, and what is captured on CCTV. In addition, this category includes three aggravating factors identified by investigation leaders as making it more difficult to prove a crime and, therefore, leading to a lower prioritisation of the case. The variables are dummies. Either the camera supports the victim’s account or it does not. Either the witnesses provide consistent accounts that support the suspect’s defence or they do not.

Finally, but by no means least important: Since deadly violence is often preceded by early warnings, such as less serious violent behaviour (Caman et al., 2017; Hjertén & Rapp, 2023; Nilsson, 2002; Socialstyrelsen, 2024), the suspect’s criminal record may have an impact on the investigator’s decisions. Even though all individuals should be treated equally and fairly under the law, the perpetrator’s criminal record, specifically when it comes to domestic violence and if the perpetrator has been suspected or convicted of violent crimes, is (or should be) a factor in the police’s prioritisation of cases and investigative measures (Polisen, 2023a).

4.4 Analysis

Firstly, the correlation between the dependent variable and the independent condition variables are tested (Table 1).

Table 1.

Case referred to prosecutor % | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Independent condition variables | No | Yes | n | γ |

The victim cooperates | 1.0*** | |||

- No | 100 | - | 43 | |

- Yes | 89 | 11 | 244 | |

Information about witnesses or CCTV | 0.71** | |||

- No | 97 | 3 | 117 | |

- Yes | 86 | 14 | 170 | |

The victim needs medical care | 0.53* | |||

- No | 93 | 7 | 235 | |

- Yes | 81 | 19 | 52 | |

The victim has no or minor injuries | -0.31 | |||

- No | 87 | 13 | 166 | |

- Yes | 93 | 7 | 121 | |

Information of verbal arguing | -0.83** | |||

- No | 85 | 15 | 163 | |

- Yes | 98 | 2 | 124 | |

Presence of a counter-claim report | -0.85** | |||

- No | 88 | 12 | 201 | |

- Yes | 99 | 1 | 86 | |

The suspect has a criminal record of violence a | 0.52* | |||

- No | 92 | 8 | 168 | |

- Yes | 79 | 21 | 62 | |

Total | 91 | 9 | 287 | |

Secondly, the three significant case conditions to investigate the crime are combined into one single variable that measures the “level of investigability” and tested against the dependent variable (Table 2). The variable ranges from 1 to 5, where the conditions are:

-

Optimal: Victim cooperates, there are witnesses/CCTV cameras, the victim needs medical care (5)

-

Good: Victim cooperates, there are witnesses/CCTV cameras, the victim does not need medical care (4)

-

Acceptable: Victim cooperates, there are no witnesses or CCTV cameras, the victim needs medical care (3)

-

Poor: Victim cooperates, there are no witnesses or CCTV cameras, the victim does not need medical care (2)

-

Very poor: The victim does not cooperate (1)

Table 2.

Case referred to prosecutor % | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Independent index condition variables | No | Yes | n | γ |

Level of investigability (see above) | 0.68*** | |||

- Optimal (5) | 76 | 24 | 38 | |

- Good (4) | 87 | 13 | 111 | |

- Acceptable (3) | 90 | 10 | 10 | |

- Poor (2) | 98 | 2 | 85 | |

- Very poor (1) | 100 | - | 43 | |

Level of aggravating circumstances | -0.71*** | |||

- Minor or no injuries, and arguing or counter-claim (4) | 99 | 1 | 95 | |

- Minor or no injuries, no arguing or counter-claim (3) | 96 | 4 | 56 | |

- Severe injuries, but arguing or counter-claim (2) | 87 | 13 | 98 | |

- Severe injuries, but no arguing or counter-claim (1) | 74 | 26 | 38 | |

Total | 91 | 9 | 287 | |

Thirdly, the three aggravating conditions that correlate negatively with clearance rates (the victim having no or minor injuries, the presence of verbal arguing, and a counter-claim report) were tested against the dependent variable. These were analysed separately and together in cross-tabulations and, finally, combined into one variable measuring the level of aggravating circumstances (Table 2). This variable ranges from 1 to 4 and refers to cases where the victim has:

-

Minor or no injuries, and there is arguing or a counter-claim report (4).

-

Minor or no injuries, but there is no arguing or counter-claim report (3).

-

Severe injuries, and there is arguing or a counter-claim report (2).

-

Severe injuries, but there is no arguing or counter-claim report (1).

The distribution of the three groups (strangers, acquaintances, and intimate partners) is compared based on the measures of investigability and aggravating circumstances as well as the expected investigative actions that the police have or have not taken. The results are analysed and presented in cross-tabulations, where significant differences in distribution and correlations are indicated, using chi-square (χ²) and gamma (γ).

5. Findings

The three study groups – intimate partner violence (IPV), assault against a stranger (S), assault against an acquaintance (A) – have identical clearance rates: about nine per cent was submitted to the prosecutor in all groups. However, the conditions for investigating the crimes and the police efforts or actions taken in the various investigations, differ between the groups. Mostly, this applies when it comes to the victim’s willingness to participate in the investigation. About three-quarters of the IPV victims participated compared with 81 and 95 per cent of the A and S group, respectively. Furthermore, there are significant differences between the group of IPV and strangers regarding witnesses or surveillance cameras: less than half of the IPV cases compared with three-quarters of the S group (Table 3). The results also show that victims of IPV seek medical care for injuries less frequently compared with the A and S groups. This could be explained by the fact that the violence in the IPV cases more seldom results in bleeding lacerations compared to assault between strangers and acquaintances, 13, 29 and 27 per cent, respectively.

Table 3.

Conditions | IPV | Acquaintance | Strangers | Total | Chi2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The victim cooperates | 16.*** | ||||

- No | 26 | 19 | 5 | 15 | |

- Yes | 74 | 81 | 95 | 85 | |

Information about witnesses/CCTV | 14.*** | ||||

- No | 54 | 46 | 28 | 41 | |

- Yes | 46 | 54 | 72 | 59 | |

The victim needs medical care | 9.* | ||||

- No | 93 | 82 | 75 | 82 | |

- Yes | 7 | 18 | 25 | 18 | |

Level of investigability a | 29.*** | ||||

- Optimal (5) | 3 | 12 | 20 | 13 | |

- Good (4) | 33 | 33 | 47 | 39 | |

- Acceptable (3) | 2 | 5 | 4 | 4 | |

- Poor (2) | 36 | 32 | 24 | 30 | |

- Very Poor (1) | 26 | 19 | 5 | 15 | |

Total (n) | 61 | 112 | 114 | 287 | |

The suspect has a criminal record of violence b | 6.* | ||||

- No | 79 | 77 | 63 | 73 | |

- Yes | 21 | 23 | 37 | 27 | |

Total (n) | 58 | 93 | 79 | 230 |

Optimal conditions for investigation vary with perpetrator-victim relationships, being lowest in the IPV category and highest for violence between strangers (Table 3). About one-third of the IPV group have at least good conditions to be investigated (investigability 4), since there are witnesses to these crimes on this level. The corresponding proportion for acquaintances is almost half of the cases, and for strangers, two-thirds.

Regarding the perpetrator’s prior criminal activity, the results show that it is significantly less common for the perpetrator to have been convicted of a violent crime in cases of intimate partner violence, but also when the parties are acquaintances, compared with the group of strangers.

The conditions referred to in the previous section are relevant for what investigative measures are chosen. Three key measures can be identified in addition to offering a victim’s counsel. The measures are: 1) to interview all victims that cooperate when the crime is reported, 2) to interview witnesses and/or to collect CCTV footage in cases where there are witnesses/CCTV, and 3) to obtain medical records in cases where the victim has sought or might need medical care (Table 4).

Table 4.

Level of investigability | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Investigative measures | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | Total | Chi2 |

The victim has been interviewed a | 82 | 86 | 70 | 60 | 49 | 71 | 29.*** |

Witnesses/CCTV have been interviewed/checked a | 87 | 78 | 40 | 20 | 33 | 54 | 91.*** |

Retrieved medical records a | 68 | 21 | 70 | 15 | 2 | 24 | 67.*** |

The victim has been offered a victim’s counsel | 18 | 14 | 20 | 11 | 12 | 13 | n.s. |

Not done what can be expected | 40 | 29 | 30 | 40 | 23 | 33 | n.s. |

No investigative measures taken a | 3 | 5 | 20 | 26 | 33 | 15 | 32.*** |

Total (n) | 38 | 111 | 10 | 85 | 43 | 287 | |

We can observe that the police do take further investigative measures in cases, even when the initial report indicates that there are no witnesses to interview or CCTV cameras to check: in 40 per cent of the cases with an acceptable investigability level, in 20 per cent of the cases with poor (2) investigability, and as much as 33 per cent of the cases with very poor investigability (1).

What can be investigated should be investigated. It is not possible to claim that certain matters should be investigated while others should not. Much depends on what emerges from the report. Are there witnesses, or can the offence be proven by other means? Is it possible to establish intent? As time passes, the investigation becomes more difficult, and cases of common assault often do not receive the highest priority.

However, Table 4 also shows that of the investigations with optimal conditions (n=38), the police could have done more in 40 per cent of the cases, but they chose not to do so. Overall, the police could have taken additional actions in 33 per cent (n=94) of all cases. Two investigation leaders explain this in the following way:

I would never proceed with an assault case in a pub, especially if there’s a counter-claim report. Two drunk individuals – it’s not feasible. The prosecutor will likely dismiss it. In that case, I might as well close it immediately to save everyone time.

I almost always initiate an investigation if the offence is assault. However, if the situation is chaotic, unclear, or involves a very minor offence, I do not initiate an investigation. The victim must appear credible. It’s quite common for intoxicated individuals to file a report in the heat of the moment, only to later withdraw it or regret their actions.

The distribution of investigations where not all possible measures have been taken is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

IPV | Acquaintance | Strangers | Total | Chi2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Done what can be expected | 15.** | ||||

- Yes | 87 | 65 | 59 | 67 | |

- No, even though the victim cooperates | 8 | 24 | 32 | 24 | |

- No, but the victim does not cooperate | 5 | 11 | 9 | 9 | |

Total (n) | 61 | 112 | 114 | 287 |

As shown in Table 5, it seems that the shortcomings of not implementing expected measures are less common when the violence has occurred in intimate relationships (13%) compared with violence between strangers (41%).

Sometimes I choose not to close the case immediately, so that the victim does not feel dismissed right away, it can be perceived as insensitive […] We must not forget the crime-preventive effect; we apply a significantly lower threshold when it comes to particularly vulnerable victims.

However, of the total 94 cases with shortcomings (33%), the victim cooperates in the majority (n=69) of the cases. In the next section these cases are examined for the possible reasons why action was not taken.

One is fairly proactive early on. What does the report indicate? Is there any evidence suggesting that initiating the investigation is unwarranted? If we can quickly determine that this is unlikely to lead to any meaningful results, we should avoid allocating unnecessary resources to it.

You know, two intoxicated troublemakers in a bar, that’s a completely different matter. If it involves minor violence and the victim does not wish to seek medical attention, then, well, I sure have a solid basis for not initiating an investigation.

We have a clear objective, and that is to keep the balance down. We must be efficient; everyone follows the national investigation strategy. We are to investigate those that lead to prosecution and allocate resources to the right cases.

In cases where the police, even though the victim cooperated in the entire investigation, did not undertake all the expected investigative actions, only seven per cent lack aggravating circumstances, such as minor or no injuries, arguments, or counter-claim reports (Table 6). While most cases involving IPV include two or more aggravating circumstances, the corresponding proportions for the two other groups are lower.

Table 6.

IPV | Acquaintance | Strangers | Total | Chi2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Level of aggravating circumstances | 7. | ||||

- Minor or no injuries, and arguing or counter-claim (4) | 60 | 26 | 24 | 28 | |

- Minor or no injuries, no arguing or counter-claim (3) | 20 | 11 | 24 | 19 | |

- Severe injuries, but arguing or counter-claim (2) | 20 | 59 | 41 | 46 | |

- Severe injuries, but no arguing or counter-claim (1) | - | 4 | 11 | 7 | |

Total (n) | 5 | 27 | 37 | 69 |

In 45 cases where the victim cooperated, they were never questioned. Five of these 45 are IPV cases. In one of these five cases, the investigation leader chose not to initiate an investigation as the incident did not constitute a crime. In the second case, the assessment was that there was reason to believe there could potentially be a crime, but it occurred so long ago that the statute of limitations had expired. In the third case, it was evident that the suspect admitted during questioning to having inflicted violence on the victim by pushing her. However, the suspect claimed that he lacked intent and that it was an unfortunate circumstance that she was injured. This case was closed due to lack of evidence. The report indicated that the parties had an argument, and the case included a counter-claim report. Also, the fourth case involved an argument beforehand, and the injury was minor as the suspect had merely held the victim’s arm tightly. The fifth case included a male victim, a female perpetrator, and a counter-claim report. The witness in the case had not been questioned.

If there are witnesses, they should be interviewed. I see no reason not to. Possibly if it becomes clear from the victim’s interview that the listed witness didn’t see anything or is a friend of the victim. But it’s really strange not to do it. I don’t understand.

No, that’s not the case. We do interview witnesses. But if the victim doesn’t want to, intoxication level shouldn’t matter, but I know it does. If there’s no note about witnesses in the report, I assume there aren’t any. I can’t read the whole investigation and all the interviews before making a decision. There’s simply no time.

Most of the witnesses in the IPV cases were interviewed. Five per cent of the witnesses were not interviewed even if the victim was willing to cooperate. In contrast, for the other two groups, it is a more common “measure not taken”, accounting for 26 per cent and 20 per cent of cases where the victim cooperated.

There is one type of case where I always initiate an investigation: when the crime has occurred within an intimate relationship. In such instances, it is crucial to investigate, as the report may be just the tip of the iceberg.

Finally, there is one investigative measure that shall be taken when an investigation regarding assault has been initiated: a victim’s counsel shall be offered to the victim, regardless of the relation between the two parties. From Table 7, it appears that the police do not comply with the law in this regard.

Table 7.

IPV | Acquaintance | Strangers | Total | Chi2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Victim offered victim’s counsel | 61.*** | ||||

- Not offered | 57 | 88 | 98 | 86 | |

- Offered, not accepted | 25 | 2 | - | 6 | |

- Offered, accepted | 18 | 10 | 2 | 8 | |

Total (n) | 56 | 99 | 107 | 262 |

If there is no supporting evidence at all, then I do not initiate an investigation. You cannot press charges based on one person’s word against another’s. There must be something that supports the victim’s account. Then there is no reason to offer a victim’s counsel either.

Less than half (43%) of the IPV group was offered a victim’s counsel. Of them, a majority did not accept this offer, while about 18 per cent accepted. Even if these rates are low, they are significantly higher than the cases that included strangers and acquaintances. Of the 24 victims who were offered a victim’s counsel, less than half continued during the full investigation without dropping out. Within the group of IPV victims who accepted a victim’s counsel, the clearance rate was 21 per cent. Within the group who accepted, and did not drop out, the clearance rate was 50 per cent.

Of 230 suspects with a Swedish identification number, the proportion of initiated investigations was about the same among those who were known for previous violent behaviour compared with those who were not (92% and96%), respectively. At the same time, the clearance rate in the group of recidivists is three times higher. A total of 62 of the identified suspected perpetrators have a prior violent record. In the group of IPV there were two cases where an investigation was not initiated, even though the perpetrator was known as violent. In the group of acquaintances there were three and in the group of strangers there were none.

Table 8 shows that significantly more victims of IPV drop out during the investigation process compared with those that involved strangers or acquaintances. The proportion of those unwilling to participate was 26 per cent in the initial phase of the investigation but increased to 53 per cent during the process. It was more common for witnesses or surveillance footage to provide evidence of the victim’s account in cases where the parties were strangers than among acquaintances or in an intimate relationship. However, it was more common for the perpetrator to confess when the violent crime occurred in a close relationship. Finally, it is noteworthy that in 18 per cent of the cases there was evidence that supported the victim’s story, and the victim cooperated throughout the process. Yet only nine per cent was reported to the prosecutor. However, it seems like this shortcoming is less common among IPV and cases that involved acquaintances (13% and 10%, respectively) compared with the group of strangers (26%).

Table 8.

IPV | Acquaintance | Strangers | Total | Chi2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The victim cooperates the entire investigation | 28.*** | ||||

- No | 53 | 34 | 15 | 30 | |

- Yes | 48 | 66 | 85 | 70 | |

The suspect confesses | n.s. | ||||

- No | 93 | 97 | 99 | 97 | |

- Yes | 7 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

Witnesses or CCTV provides evidence of the victim’s story | n.s. | ||||

- No | 80 | 81 | 71 | 77 | |

- Yes | 20 | 19 | 29 | 23 | |

Of which the victim cooperates throughout | 10 | 13 | 26 | 18 | 9.** |

Witnesses or CCTV provides evidence of the suspect’s defence | n.s. | ||||

- No | 95 | 94 | 93 | 94 | |

- Yes | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 | |

Total (n) | 61 | 112 | 114 | 287 |

5.1 Summary

The primary objective of this study was to enhance understanding of the police’s role in investigating intimate partner violence. While the police are expected to prioritise cases involving violence in close relationships, they must also operate efficiently, focusing on crimes likely to result in imprisonment.

This is a judgement-based field we are engaged in. Fundamentally, the scope is limited, but we have stretched it quite a bit. The problem is not the difficulty of the crimes, but the enormous volume. We close cases all day long. In nine out of ten cases, the victim does not file a complaint. The minimum one can do is “nothing”; experienced or seasoned investigators tend to make overly far-reaching predictions. After handling 1,000 of these cases and getting the wrong outcome in 998 of them, one tends to predict that this won’t lead anywhere. We must treat each case with the respect it deserves, but it is difficult when 25 new cases come in during each shift.

The results illustrate that the conditions for investigating non-aggravated IPV crimes are limited. The primary reason for this is the low acceptance rate to cooperate among victims and the consequences of this. Only one-third of the victims, even when witnesses are present, wanted to participate in the investigation from the start and less than half of the participating victims continued to cooperate during the full investigation. This raises an important question of a strategy for the police to influence the victim’s acceptance to participate fully throughout the investigation process.

One alternative is to offer and improve the victim a victim’s counsel. The results indicate that the police offer victim counselling to non-participating victims, when the investigation leader believes that a conviction is likely if the victim changes their mind and chooses to participate. In the dataset, not a single victim who initially declined to cooperate later changed their mind and agreed to participate. If the police are to improve clearance rates, they must succeed in persuading more victims to cooperate – or more suspects to confess. However, the conditions for achieving this are not ideal, as the police are expected to close investigations when prosecution is not anticipated.

6. Discussion

This study has shown that there are important differences in investigability between investigations of assault in IPV and assaults in other contexts. IPV investigations more often involve minor injuries, verbal altercations, and counter-reports. These cases also more frequently lack witnesses, and IPV victims are less likely to cooperate with the police. These aggravating circumstances pose several challenges for the investigation leader. In the following section, we discuss how these differences in investigability may influence police decision-making during the investigation process and how the police may navigate conflicts in prioritisation.

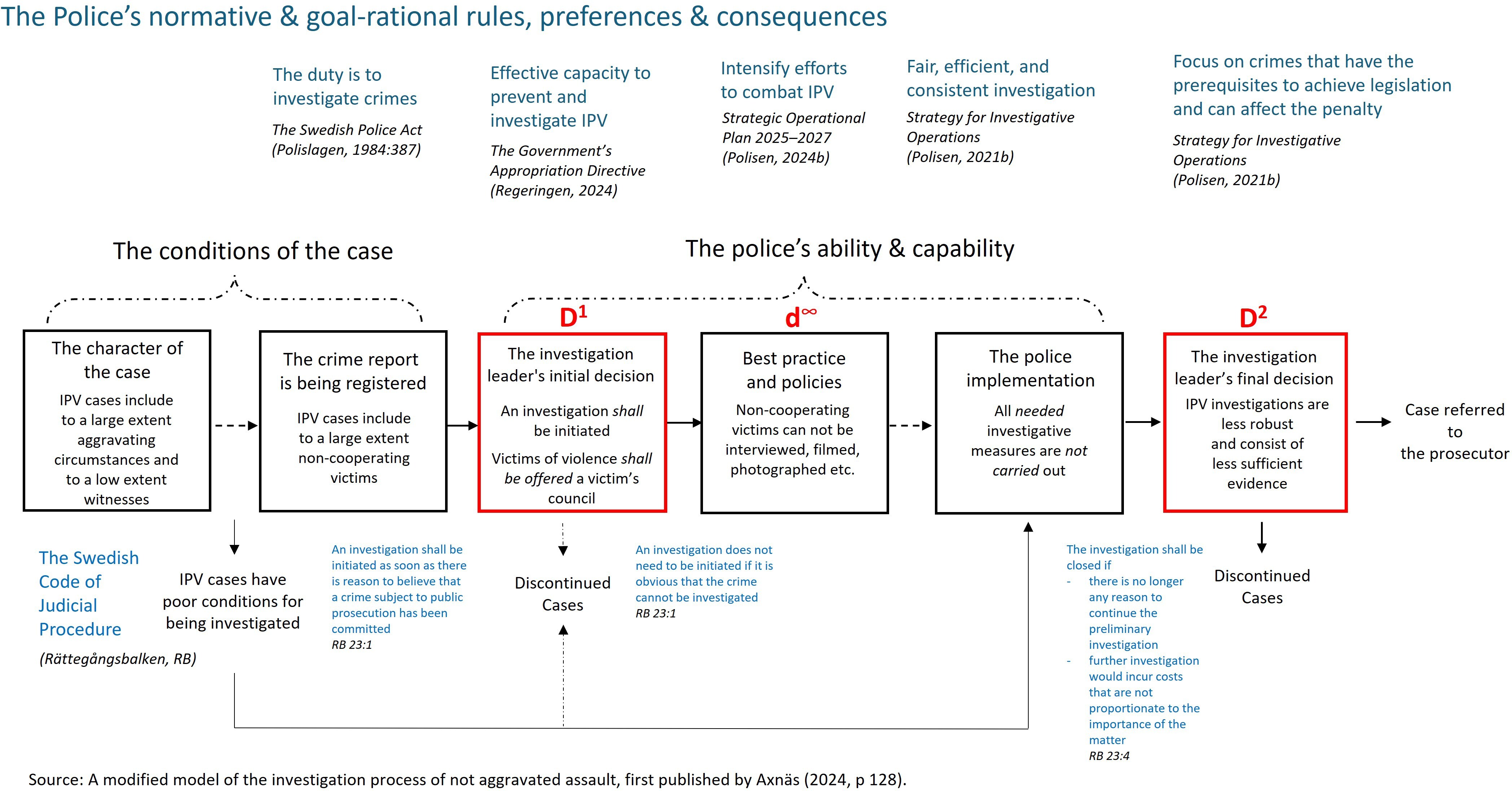

The discussion in this study can advantageously be applied to a modified version (see Figure 1) of the investigative process model previously published by Axnäs (2024).

Figure 1.

The investigation process for non-aggravated assault in intimate partnerships

Verbal altercations, in combination with counter-reports and less severe injuries, are circumstances which, according to the interviewed investigation leaders, often indicate that prosecution is unlikely. If the prognosis for prosecution is not positive, the investigation is typically discontinued on the grounds that the offence cannot be substantiated (Polisen, 2021b). Nonetheless, a certain number of IPV cases are still forwarded to the prosecutor, which is somewhat unexpected. This may be due to the police – driven by organisational goals, albeit in tension with operational strategy – continuing to prioritise and address violence within close relationships, even when such violence is less severe and more challenging to investigate. Victims of IPV are offered a victim’s counsel more frequently than victims in other categories. However – and this is notably surprising – if the victim is unwilling to cooperate, a victim’s counsel is less often provided. This may suggest that street-level bureaucrats prioritise vulnerable victims as long as the victim acknowledges their vulnerability and actively accepts help from the police.

If the victim does not cooperate during the initial interview, no formal statement is obtained, making other initial investigative measures more difficult to carry out. These include, for example: identifying potential witnesses, securing the crime scene for traces or evidence, conducting a search of the victim’s residence, arresting the suspect (often based on the victim’s statement), documenting injuries through photographs or video, and obtaining medical or forensic certificates. In the present study, crime scene investigations by forensic experts were not even included as a variable – simply because such measures were almost never undertaken. One reason for this is that minor injuries typically do not leave blood traces or visible evidence in the same way as more serious injuries. Furthermore, this study didn’t involve variables about why victims don’t want to cooperate or how the police handle them, how often, or in what ways the non-cooperating victims had been contacted, nor what arguments were used to encourage their cooperation.

-

Further qualitative research is therefore highly relevant for understanding what might motivate more Swedish IPV victims to cooperate. Based on such insights, targeted educational efforts and interventions could be developed.

Interviews with police investigation leaders confirm that, in assault investigations, interviewing the victim is the most fundamental investigative measure available. As the most common and critical source of information (Polisen, 2023b), the victim interview often forms the foundation of the investigation. This is where police officers can play a significant role by collecting relevant details from the victim’s statement – details that can, in turn, lead to additional measures such as involving forensic experts. Despite this, the results of the study show that interviews with IPV victims are not always conducted.

Given the variation in case characteristics, the decision-making process of the police may be considered relatively rational – particularly when necessary information cannot easily be obtained, leaving the evidentiary basis too weak to proceed. It can be assumed that investigation leaders act rationally under these conditions. If a victim refuses to cooperate, the prosecutor typically lacks a case. However, in situations where other forms of evidence may support the victim’s initial account – despite the victim’s later refusal to cooperate – the investigative leader must weigh the victim’s reluctance against the police’s legal duty to investigate, while also considering operational efficiency and the likelihood of a successful prosecution. As one investigation leader expressed, the conflicting goals of investigating fewer cases while simultaneously increasing the clearance rate are difficult to manage:

They only inform you about what to prioritise but not what to deprioritise. If you prioritise some cases, others must be set aside, but no guidance is provided. We can no longer examine every avenue, not even for vulnerable victims like those experiencing IPV.

According to the government’s appropriation directive (Regeringen, 2024) and the police strategic operational plan (Polisen, 2024b), law enforcement is expected to demonstrate a strong ability to prevent and investigate male violence against women, and to ensure that investigative practices are fair, efficient, and consistent. At the same time, the police function as a street-level bureaucracy – a type of organisation that must develop internal strategies to manage and ration the inflow of cases, as demand for services often exceeds available resources. While laws and regulations limit discretion, they also create opportunities (Jönsson, 2021). Discretion may operate in both directions. On the one hand, an investigator may argue – based on prior experience – that a victim who refuses to cooperate rarely changes their stance, and that prosecutors are unlikely to pursue charges without the victim’s participation. In such cases, rationing investigative resources becomes not only a pragmatic choice, but an organisational imperative. Time spent on cases unlikely to lead to prosecution is time lost on cases with more promising outcomes. On the other hand, such assumptions may be based on outdated data and working methods. If the police manage to convince more victims to cooperate, the number of successful prosecutions may increase, and the investigation leaders’ experiences – and expectations – might shift accordingly.

Victims who do not participate pose a well-documented challenge for the criminal justice system (Davis, 1983). Still, what is actually said during interviews aimed at persuading victims to cooperate appears to be of critical importance. It is reasonable to assume that these conversations vary depending on whether the investigator is motivated by procedural efficiency (e.g., closing a case quickly) or by a broader goal, such as reducing violence against women or encouraging perpetrators to cease using violence.

One investigation leader described this dilemma clearly:

It’s much easier to initiate an investigation and then close it citing a non-cooperative victim than to assign the case to an already-stressed investigator, asking them to influence the victim when experience shows that it probably won’t lead anywhere.

In such instances, the judgement of the investigation leader is that the case is unlikely to result in a conviction. However, if there is supporting evidence for the victim’s statement, it could be argued that assigning a victim’s counsel might help reduce the victim’s reluctance. Yet, this study also shows that even cooperative victims are not always offered a victim’s counsel. This may suggest that police responses are not only guided by procedural rules but are also shaped by their assessment of the victim’s perceived vulnerability and willingness to engage. Research indicates that many women report domestic violence not primarily to ensure a conviction, but to assert that the violence is unacceptable and to stop the immediate threat (Belfrage & Strand, 2012; Marklund & Nilsson, 2008; Nilsson, 2002; Scheffer Lindgren, 2009). This highlights the need for a broader understanding of victims’ motivations and expectations when interacting with the police.

It is important to recognise that the investigative process is not static, but a dynamic sequence of actions and decisions. At the initial stage, in cases when the violence is not severe, the police may choose to place less emphasis on achieving prosecution and instead focus on preventive efforts – such as outreach and persuasive conversations aimed at encouraging victim cooperation. For example, in one Local Police District (LPO) in Stockholm, officers have begun applying such preventive strategies in practice. These efforts align with findings from Petersen et al. (2022), who conducted a meta-analysis of various preventive interventions. Their analysis suggests that so-called second-responder programmes appear promising in theory, but have limited impact in actually reducing repeat incidents of domestic violence (Petersen et al., 2022). While this may be seen as a positive outcome – suggesting improved access to support services – the overall conclusion is that second-responder programmes require further research. More established and evidence-based methods may be more effective in preventing intimate partner violence (Petersen et al., 2022).

Since legislative reforms in 1982 (Regeringen, 1981), domestic violence has been recognised in Sweden as a societal issue warranting state intervention, rather than a private family matter. Against this backdrop, there is a strong case for considering new legislative or procedural reforms. Notably, after the data collection for this study, several important changes occurred. As of 2022, national guidelines permit frontline officers to use body-worn cameras (Polisen, 2022c), which can be activated immediately upon arriving at a crime scene. This development allows for the recording of the initial victim contact without needing a formal setting (e.g., with camera and tripod). Since the present study shows that victims are more likely to cooperate at the scene than one or two days later, the ability to record the victim’s statement immediately may significantly increase the effectiveness of early police intervention.

Given the low clearance rate and high number of discontinued IPV investigations, it is essential for law enforcement to continue developing both technological tools and systematic follow-up mechanisms. These should not only assess the prerequisites for investigation but also document and evaluate alternative interventions – such as risk assessments, referrals to men’s support services, and counselling options for both victims and perpetrators – in cases where prosecution is not feasible. Persuading an uncooperative victim to participate can be difficult through dialogue alone. However, when the police demonstrate through action that the crime is taken seriously – by, for example, involving forensic specialists or maintaining consistent follow-up contact with the victim – it can help build trust and convey the seriousness of the offence. In autumn 2024, the Stockholm Police Region made a strategic decision to pilot an initiative involving forensic experts in cases of intimate partner violence (Polisen, 2024a). For 12 weeks in spring 2025, officers taking reports were instructed to contact the forensic coordinator when the incident involved close relationships. The aim was to increase the use of forensic resources and awareness among frontline and investigative personnel handling IPV cases.

Finally, a key distinction must be made regarding the police’s role in IPV investigations. The investigative process consists of several formal decisions – such as initiating an investigation or conducting specific measures – which are clearly structured in terms of time and responsibility. However, in IPV cases, the investigation leader is (or should be) a prosecutor. This means that key decisions – especially regarding whether an investigation should be closed – are usually made by the prosecutor. Therefore, the police’s formal role in influencing the legal outcome of a case must be seen as limited.

Given this limitation, it may be more productive for the police to focus on what they can actually control: the content and quality of the conversation with the victim, and the early preventive measures taken. Since 2004, the Swedish police have worked to improve initial crime scene responses (Polisen, 2004, 2012, 2014, 2023a, 2023c, 2024b, 2022b). However, national monthly follow-ups still primarily measure outcomes that are dependent on the prosecutor’s decisions – such as the number of cases referred for prosecution (Polisens, 2007a, 2010a, 2022e). Perhaps the conflict around prioritisation could be eased if investigative leaders were evaluated based on factors within police control – such as victim engagement, early documentation efforts, or other investigability indicators. Setting measurable goals for these actions might better align police performance with the long-term aim of reducing intimate partner violence.

7. Conclusions

This study draws one important conclusion about IPV investigations in Stockholm in Sweden: the police’s ability to investigate cases of intimate partner violence is insufficient. The main issue seems to be the conflict between the high priority given to such cases, the fact that they less often lead to prosecution, and the recommendation not to allocate resources to cases with low prosecution rates. Many investigative measures that could and should be conducted are not being carried out, likely due to these conflicting recommendations. However, it is important to notice that in IPV investigations the prosecutor is the formal decision maker in the role as investigation leader.

While the police are instructed to offer legal counsel to victims, these offers are frequently declined. Similarly, although the police are advised to video-record interviews, this is not always feasible due to limited access to appropriate equipment or the victim’s reluctance to be filmed. Given the insufficient conditions to investigate and resolve these crimes, the police must at least do what they are supposed to do when it comes to violent crimes: to offer the victim legal counsel, to increase their knowledge about what works and how victims may change their position and become willing to cooperate and finally, utilise forensic teams in larger extent when the violence is not severe. This may both increase the victim’s willingness to cooperate and improve clearance rates.

8. Limitations

The study only includes investigative measures and risk-reducing interventions (RRI) that are documented in the police investigation system. Investigative measures and RRI such as risk assessments, referring the perpetrator to support centres, and applying for restraining orders were not regularly reported in 2016–2021.

References

-

Axnäs, N. (2024).

Utredningsbara misshandelsbrott? En studie av polisens förutsättningar och förmåga att utreda och klara upp misshandelsbrott

.Malmö University Press

. https://doi.org/10.24834/isbn.9789178774456 -

Belfrage, H.&Strand, S. (2012). Measuring the outcome of structured spousal violence risk assessments using the B‐SAFER: Risk in relation to recidivism and intervention.

Behavioral Sciences & the Law

, 30 (4), 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2019 -

Brodkin, E.Z. (2011). Policy work: Street-level organizations under new managerialism.

Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

, 21 (Supplement 2), i253–i277. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq093 -

Caman, S.,Howner, K.,Kristiansson, M.&Sturup, J. (2017). Differentiating intimate partner homicide from other homicide: A Swedish population-based study of perpetrator, victim, and incident characteristics.

Psychology of Violence

, 7 (2), 306. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000059 -

Coupe, R.T. (2016). Evaluating the effects of resources and solvability on burglary detection [Article].

Policing & Society

, 26 (5), 563–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2014.989155 -

Coupe, T.&Griffiths, M. (1996).

Solving residential burglary

.Citeseer

. -

Coupe, T.&Griffiths, M. (2000). Catching offenders in the act: An empirical study of police effectiveness in handling ‘immediate response’ residential burglary.

International Journal of the Sociology of Law

, 28 (2), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1006/ijsl.2000.0120 -

Davis, R.C. (1983). Victim/witness noncooperation: A second look at a persistent phenomenon.

Journal of Criminal Justice

, 11 (4), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2352(83)90069-7 -

Eksten, A. (2009). Olika förundersökningsledare - olika beslut 2009:8.

Brottsförebyggande rådet (BRÅ)

. https://doi.org/https://bra.se/publikationer/arkiv/publikationer/2009-03-26-olika-forundersokningsledare---olika-beslut.html?lang=sv -

Ekström, V.&Lindström, P. (2015). I rättvisans tjänst: leder stöd till våldsutsatta kvinnor till fler åtal? The Fifth Biennial Nordic Police Research Seminar, August 19–21, 2014, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden.

-

Franke Björkman, K.&Fjelkegård, L. (2024). Polisens utredning av grova brott och brott mot särskilt utsatta brottsoffer (Vol. 2024:9).

Brottsförebyggande rådet

. https://doi.org/https://bra.se/publikationer/arkiv/publikationer/2024-10-17-polisens-utredning-av-grova-brott-och-brott-mot-sarskilt-utsatta-brottsoffer.html?lang=sv -

Freidson, E. (1988). Theory and the professions.

Ind. LJ

, 64 , 423. https://doi.org/https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol64/iss3/1?utm_source=www.repository.law.indiana.edu%2Filj%2Fvol64%2Fiss3%2F1&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages -

Greenwood, P.W.&Petersilia, J. (1975).

The criminal investigation process volume I: summary and policy implications

. -

Hansen, S.B.&Møller Okholm, M. (2024). Drab i Danmark 2017–2021. https://doi.org/https://www.justitsministeriet.dk/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Drab-i-Danmark-2017-2021_WT.pdf

-

Hjertén, L.&Rapp, J. (2023). Dödade kvinnor [Jornalistiskt arbete]. https://doi.org/https://www.aftonbladet.se/nyheter/a/0G3n6A/dodade-kvinnor

-

Horvath, F.,Meesig, R.T.&Lee, Y.H. (2001). A national survey of police policies and practices regarding the criminal investigation process: Twenty-five years after Rand.

The National Institute of Justice

. https://doi.org/https://www.ojp.gov/library/publications/national-survey-police-policies-and-practices-regarding-criminal -

Jansson, K. (2005).

Volume crime investigations: a review of the research literature

. (Vol. 44.).Citeseer

. -

Jönsson, A. (2021). Handlingsutrymme i en professionell kontext.

Linde, S., & Svensson, K.(Red.), Välfärdens aktörer: utmaningar för människor, proffessioner och organisationer

, 181–211. https://doi.org/10.37852/oblu.118 -

Lag . (1988:609). om målsägandebiträde.

-

Liederbach, J.,Fritsch, E.J.&Womack, C.L. (2011). Detective workload and opportunities for increased productivity in criminal investigations [article].

Police Practice & Research

, 12 (1), 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2010.497379 -

Liljegren, A.,Berlin, J.,Szücs, S.&Höjer, S. (2021). The police and ‘the balance’—managing the workload within swedish investigation units.

Journal of Professions and Organization

, 8 (1), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/joab002 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/joab002 -

Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: dilemmas of the individual in public service.

Russell Sage Foundation

. https://doi.org/https://www.russellsage.org/sites/default/files/Lipsky_Preface.pdf -

March, J.G. (1994).

Primer on decision making: how decisions happen

.Simon and Schuster

. -

Marklund, F.&Nilsson, A. (2008).

Polisens Utredningar Av Våld Mot Kvinnor i Nära Relationer

. https://doi.org/https://bra.se/publikationer/arkiv/publikationer/2008-12-15-polisens-utredningar-av-vald-mot-kvinnor-i-nara-relationer.html?lang=sv -

Neyroud, P. (2011). Valuing investigations.

Policing

, 5 (1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/par001 -

Nilsson, L. (2002). Våld mot kvinnor i nära relationer: en kartläggning.

Brottsförebyggande rådet (BRÅ)

. https://doi.org/https://bra.se/publikationer/arkiv/publikationer/2002-05-09-vald-mot-kvinnor-i-nara-relationer.html?lang=sv -

Petersen, K.,Davis, R.C.,Weisburd, D.&Taylor, B. (2022). Effects of second responder programs on repeat incidents of family abuse: An updated systematic review and meta‐analysis.

Campbell Systematic Reviews

, 18 (1), e1217. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1217 -

Polisen . (2004).

Polisens nationella utredningskoncept. Slutrapport

. -

Polisens . (2007a). Polisens Årsredovisning 2007 Rikspolisstyrelsen.

-

Polisen . (2007b). Verksamhetsplan 2008. Polismyndigheten i Stockholms län.

-

Polisens . (2010a). Polisens årsredovisning 2010.

-

Polisen . (2010b). Ökad effektivitet och förbättrad samverkan vid handläggning av mängdbrott: redovisning i maj 2010 av ett regeringsuppdrag till Rikspolisstyrelsen, Åklagarmyndigheten och Domstolsverket.

Rikspolisstyrelsen

. http://www.polisen.se/Global/www%20och%20Intrapolis/Rapporter-utredningar/01%20Polisen%20nationellt/Ovriga%20rapporter-utredningar/Okad_effektivitet_o_forbattrad_samverkan_vid_handlaggning_av_mangdbrott.pdf -

Polisen . (2012).

Initiala utredningsåtgärder med fokus på patrullernas rapportering: fördjupad uppföljning ur ett effektivitetsperspektiv

.Rikspolisstyrelsen

. -

Polisen . (2013).

Verksamhetsplan 2014

.Polismyndigheten Stockholms län

. -

Polisen . (2014). OP 15 Polisens nationella utredningskoncept (PNU): rapport. Genomförandekommittén för nya Polismyndigheten, Regeringskansliet.

-

Polisen . (2016). Checklista för utredning av våld i offentlig miljö.

-

Polisen . (2019).

Polismyndighetens strategiska verksamhetsplan för 2020-2024

.Polismyndigheten

. -

Polisen . (2020). Årsredovisning 2020 (Polismyndigheten, Ed.). https://doi.org/https://polisen.se/aktuellt/publikationer/?lpfm.cat=454

-

Polisen . (2021a). Polisens nationella utredningsdirektiv. https://intrapolis.polisen.se/bekampa-brott/utredningsverksamhet/framgangsfaktorer-utredningsverksamheten-pnu/

-

Polisen . (2021b).

Polismyndighetens strategi för utredningsverksamheten

.(saknr 124)

. -

Polisen . (2022a). Checklista för initiala åtgärder på brottsplatsen (våld i nära relation).

Polismyndigheten

. Accessed 1 June 2022 https://intrapolis.polisen.se/bekampa-brott/metoder-stod-atgarder/checklistor/checklistaatgardskort-for-initiala-atgarder-pa-brottsplatsen-vald-i-nara-relation/ -

Polisen . (2022b). Polismyndighetens handbok för PNU - Polisens nationella utredningsmetodik 2022:24 (Vol. A682.550/2022). Polisen.

-

Polisen . (2022c).

Polismyndighetens riktlinjer för kroppsburna kameror - PM 2022:26 - A236.571/2022

.Polismyndigheten

. -

Polisen . (2022d). VUP - Verksamhetsuppföljning. https://bi.polisen.se/vup.htm

-

Polisen . (2022e).

Årsredovisning 2022

. -

Polisen . (2023a). Initiala utredningsåtgärder vid brott mot särskilt utsatta brottsoffer. In

Brottsbekämpning

.Polismyndigheten

. -

Polisen . (2023b).

Polismyndighetens handbok för förhör 2023:02

.Polismyndigheten

. -

Polisen . (2023c). Polismyndighetens synpunkter med anledning av Riksrevisionens granskningsrapport Polisens hantering av mängdbrott.

-

Polisen . (2024a).

Inriktningsbeslut gällande en Pilot avseende tvingande kontakt med forensisk samordnare vid brott i nära relation under 2025

.Polisregion Stockholm

. -

Polisen . (2024b).

Strategisk verksamhetsplan 2025–2027

.Polismyndigheten

. -

Polisen . (2024c). Verksamhetsuppföljning polisen (VUP) [Databas för verksamhetsuppföljning].

-

Polisförordningen . 2014:1104.

-

Polislagen . 1984:387.

-

Regeringen . (1981).

Proposition 1981/82:43 – Om åtal för vissa brott m.m., (1981/82:43)

. -

Regeringen . (2006). Regleringsbrev för budgetåret 2007 avseende Rikspolisstyrelsen och övriga myndigheter inom polisorganisationen.

-

Regeringen . (2019).

Regleringsbrev för budgetåret 2020 avseende Polismyndigheten

. -

Regeringen . (2024). Regleringsbrev för budgetåret 2025 avseende Polismyndigheten.

Regeringen

. https://doi.org/https://www.esv.se/statsliggaren/regleringsbrev/?RBID=24814 -

Riksrevisionen . (2023).

Polisens hantering av mängdbrott - en verksamhet vars förmåga behöver förstärkas

.Riksrevisionen

. -

Robinson, A.&Tilley, N. (2009). Factors influencing police performance in the investigation of volume crimes in England and Wales.

Police Practice and Research: An International Journal

, 10 (3), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614260802381091 -

Rättegångsbalken . 1942:740.

-

Scheffer Lindgren, M. (2009). “Från himlen rakt ner i helvetet”: Från uppbrott till rättsprocess vid mäns våld mot kvinnor i nära relationer.

Karlstads universitet

. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A211156&dswid=7400 -

Socialstyrelsen . (2024). Socialstyrelsens utredningar av vissa skador och dödsfall 2022-2023 (Vol. 2024-1-8880).

Socialstyrelsen

. https://doi.org/https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/kunskapsstod-och-regler/omraden/vald-och-brott/skade-och-dodsfallsutredningar/utredningar-med-vuxna-som-brottsoffer/ -

Tilley, N.,Robinson, A.&Burrows, J. (2012). The investigation of high-volume crime . In

Handbook of criminal investigation

. (pp. 252–280).Willan

. -

Vatnar, S.K.B. (2015). Partnerdrap i Norge 1990–2012. En mixed methods studie av risikofaktorer for partnerdrap, 1. https://doi.org/https://sifer.no/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Partnerdrap_web.pdf

-

Vatnar, S.K.B.,Friestad, C.&Bjørkly, S. (2022). Intimate partner homicides in Norway 1990–2020: An analysis of incidence and characteristics.

Journal of Interpersonal Violence

, 37 (23–24), NP21599–NP21625. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211063508

- 1Level of significance: * <5%, ** <1%, *** <0.1%

- 2Only suspects with Swedish personal identity number (social security number) are included

- 3Level of significance: * <5%, ** <1%, *** <0.1%

- 4Note: Level of significance: * < 5%, ** < 1%, *** < 0.1%

- 5Three cells (20%) have an expected count less than five. The minimum expected count is 2.13.

- 6Only suspects with a Swedish personal identity number (social security number) are included.

- 7Note: Level of significance: * < 5%, ** < 1%, *** < 0.1%

- 8One cell (10%) has an expected count less than five.

- 9Note: Expected investigative measures include interviewing the victim if they cooperate, interviewing witnesses/taking action regarding surveillance cameras if available, and requesting permission to access the victim’s medical records if they seek medical treatment.

- 10Note: The differences are not significant, p > 5%

- 11Note: Two cells (22%) have expected count less than five. The minimum expected count is 3.42.

- 12To “refer a case to the prosecutor” means that the police submit a completed investigation to the prosecutor for further assessment. This happens when the investigation is finished and contains enough information for the prosecutor to decide whether charges should be filed. In this process, the prosecutor reviews the evidence and decides whether there is sufficient basis to take the case to court or whether it should be closed without charges.

- 133 kap. 5 § Brottsbalken.

- 14

- 15My translation of the wording in the Code of Judicial Procedure (Rättegångsbalken) Chapter 23, § 4.

- 16My translation of the wording in the Code of Judicial Procedure (Rättegångsbalken) Chapter 23, § 4a.

- 17Including violence with an unidentified suspect.

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21The study has undergone ethical review (Dnr 2022-02598-02; Dnr 2020–01765).

- 22Of these 26, however, only 19 (73%) resulted in charges with a conviction. This means the actual clearance rate – where someone was both charged and convicted – is only seven per cent.

- 23Other measures in cases of domestic violence, such as requesting medical certificates, calling in forensic experts, and video-recording interviews, were very rare (Axnäs, 2024).

- 24What can ultimately be proven is for the court to decide.

- 25No. 1, Male.

- 26No. 9, Male.

- 27No. 4, Female.

- 28No. 10, Male.

- 29No. 6, Female.

- 30No. 10, Male.

- 31No. 5, Female.

- 32No. 4, Female.

- 33No. 2, Female.

- 34No. 3, Female.

- 35Lag (1988:609) om målsägandebiträde.

- 36No. 5, Female.

- 37No 8, Male.

- 38No. 8, Male.

- 39No. 7, Female.