Online Romance Fraud as a Form of Emotional and Economic Partner Violence: A Social-Ecological Framework of Enabling Factors

Publisert 19.12.2025, Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing 2025/2, Årgang 12, side 1-22

Online romance fraud (ORF) is a complex form of cyber-enabled fraud, characterised by manipulative techniques and dynamics akin to those observed in domestic violence, coercive control, and intimate partner violence. In ORF, fraudsters employ persuasive strategies to build trust and establish fictitious relationships, subsequently exploiting victims financially and emotionally. This article examines ORF and identifies enabling factors, including risk and protective factors, that contribute to ORF. The analysis draws on findings from scholarly and grey literature and is guided by the social-ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986; Stokols, 1996, 2018) and routine activity theory (Cohen & Felson, 1979), both of which inform holistic crime prevention. The analysis highlights the multifaceted enabling factors and dynamics that influence ORF susceptibility and victimisation, particularly in the Nordic and Norwegian contexts. This article offers a holistic framework to address ORF and enhance crime-prevention strategies, conceptualising the phenomenon as a hybrid of cyber-enabled fraud and emotional and economic partner violence, thereby informing future research and practice.

Keywords

- romance fraud ;

- domestic violence ;

- intimate partner violence ;

- coercive control ;

- crime prevention ;

- preventive policing ;

- social-ecological

1. Introduction

Four and a half months after meeting through an online Norwegian dating service, Tove obtained a NOK 320,000 loan and sold her car, resulting in a NOK 380,000 financial loss to the man she believed to be a genuine romantic partner. In hindsight, she described the experience as a form of psychological abuse, stating that she had been manipulated and controlled by “David”, who had exploited her trust (Mæland, 2018).

Online romance fraud (henceforth referred to as ORF) is a complex form of cyber-enabled fraud. In ORF, as portrayed in the aforementioned media case, fraudsters pretend to initiate a relationship through digital technologies with the intent of exploiting their victims financially (Whitty, 2013b). ORF is a growing phenomenon that affects hundreds of thousands of individuals worldwide (Buchanan & Whitty, 2014; Cross, 2022; Cross et al., 2018). The underlying mechanisms of (online) romance fraud resemble practices of domestic violence, coercive control, and intimate partner violence (IPV), such as the distortion of victims’ reality, economic abuse, isolation, fear, and threats (see e.g., Carter, 2021; Cole, 2024; Cross et al., 2018). Beyond the economic impact on victims, there is evidence of severe psychological, emotional, or sexual harm to victims, including further criminalisation through being subject to identity crime (see, e.g., Cross & Layt, 2022) and money mule crimes (Chethiyar et al., 2021), as documented in ORF research (Buchanan & Whitty, 2014; Carter, 2021; Cross et al., 2023; Whitty & Buchanan, 2016) and through mass media and social media. In extreme cases, ORF victims have experienced suicidal ideation or attempted suicide (Chuang, 2021; Offei et al., 2022; Whitty & Buchanan, 2012b, 2016). Therefore, it is imperative to understand how these phenomena, which harm victims, their families, and the surrounding community, are enabled to establish effective preventive measures.

The purpose of this article is twofold: 1) to provide an overview and description of the phenomenon of ORF, and 2) to examine, identify and suggest enabling factors, such as risk and protective factors, that contribute to ORF, and particularly ORF susceptibility and victimisation within Nordic and Norwegian contexts. The analysis draws on findings from scholarly and grey literature and is guided by the social-ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986; Stokols, 1996, 2018) and routine activity theory (Cohen & Felson, 1979), both of which inform holistic crime prevention. The subsequent sections examine ORF and outline understandings of ORF before presenting a comprehensive, theoretically informed analysis of the multifaceted enabling factors contributing to ORF susceptibility and victimisation, particularly in the Nordic and Norwegian contexts.

2. Conceptual background

2.1 Online romance fraud

Romance fraud refers to “the phenomenon whereby a person meets a person ostensibly for romance, yet with the real purpose of defrauding them”. (Gillespie, 2017, p. 217). Facilitated by high levels of anonymity, fraudsters can access a broader and geographically diverse group of potential victims (Rege, 2009). While research on online romance fraud has grown, the literature employs multiple terms to capture the phenomenon (e.g., online dating romance scam, online romance scam, sweetheart scam/swindles). In the following, the term online romance fraud (ORF) is used because the online environment is of central importance to this article. ORF involves the illusion of a real romantic or close relationship to gain victims’ affection and trust, and ultimately illegally to obtain money from them (Lazarus et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2021). During the process of ORF, fraudsters “groom” their victims and develop a hyperpersonal relationship with them until they feel the victim is ready to share their money (Whitty, 2018). ORF includes a process (Rege, 2009; Whitty, 2013a, 2013b) and a “long-term scheme” (Carter, 2021), wherein the fraudster must establish trust and a relationship before the exploitation. Research highlights the severe consequences of victimisation in terms of the “double hit” of both financial and non-financial impacts (see e.g., Wang & Topalli, 2022; Whitty & Buchanan, 2012b, 2016).

ORF is categorised as a hybrid form of fraud – i.e., it combines two or more forms of fraud – due to its financial/socioeconomic, psychological, and psychosocial aspects (Lazarus et al., 2022; Maras & Ives, 2024). ORF diverges from other types of online fraud and is generally defined, understood, and treated as an (online) economic crime (Cross, 2020; Gillespie, 2017). However, research challenges this perspective by highlighting interpersonal and human aspects that extend beyond economic factors. Fraudsters intentionally seek to establish an emotional bond or a sense of dependency with their victims, as highlighted by Lazarus et al. (2023). Thus, ORF is considered a hybrid form of cyber-enabled fraud that belongs to several categories (Maras & Ives, 2024). It entails elements of relationship and trust fraud, as it is a convergence of romance and investment fraud (Maras & Ives, 2024). ORF is also recognised as an advanced fee fraud, often perpetrated by international criminal groups rather than solely by individual fraudsters (Whitty, 2018). Furthermore, recent studies have examined parallels between ORF and a similar hybrid investment fraud, “Sha Zhu Pan” (Chinese), also coined the “pig-butchering scam”, where fraudsters build trust to persuade victims to invest financially in commodities and online financial platforms through romantic persuasion (see, e.g., Cross, 2024; Maras & Ives, 2024; Wang, 2024; Wang & Zhou, 2022; Whittaker et al., 2024). Some previous studies have noted that the underlying mechanisms of (online) romance fraud share similarities with practices of domestic violence, coercive control, and intimate partner violence (see, e.g., Carter, 2021; Cole, 2024; Cross et al., 2018). Cross et al. (2018) have advocated for the potential for “productive dialogue” by studying the research fields of domestic violence and romance fraud together to enable effective prevention and intervention strategies.

3. Theoretical frameworks

Although the existing literature on ORF has established a connection between cyber-enabled fraud and psychological mechanisms, studies employing holistic theoretical models to investigate and comprehend the enabling factors that facilitate our understanding and prevention of exploitative and abusive behaviours are notably lacking. The social-ecological model, including the chronosystem, represents a promising theoretical framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986). Originally introduced to facilitate the understanding of human development, the social-ecological theory and approach have evolved since the 1980 s to serve holistic and transdisciplinary preventive purposes and to promote human health (Ellefsen et al., 2023; Stokols, 1996, 2018). The versatility of the social-ecological framework renders it applicable to a wide array of topics, making it a valuable starting point for a holistic approach and for describing “the connections between virtual and physical worlds” (Stokols, 2018, p. 105). According to human ecological theory, as articulated by Cohen and Felson (1979), this framework enables the exploration of how social structures produce the convergence in time and space of “likely offenders, suitable targets and the absence of capable guardians against crime” (p. 588, emphasis original).

According to Bronfenbrenner’s model (1979, p. 22) and his approach to ecological analysis, the ecological environment is a “nested arrangement of concentric structures” whereby each is part of the next level, collectively forming the structures of the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem, as well as the chronosystem. Routine activity theory (RAT) focuses on the opportunities to commit a crime, in which the presence or absence of opportunity determines when and where crimes occur (Cohen & Felson, 1979; Cullen et al., 2014). The theory posits that crime in society has increased because of changes in activities and people’s ways of living (Cohen & Felson, 1979; Cullen et al., 2014). A motivated offender, an attractive target/victim, and the absence of capable guardians/guardianship must be present to explain or anticipate offending or victimisation (Cohen & Felson, 1979; Pratt & Turanovic, 2016; Yar, 2005). Therefore, this article considers routine activity theory a relevant opportunity theory for investigating and capturing the ecological environment (Cohen & Felson, 1979) and addressing the dynamics linked to human action, crime, and opportunities.

In alignment with the objectives of this article, an analytical approach rooted in the social-ecological model and social-ecological theory provides a comprehensive framework for organising and analysing the relevant existing literature on the multifaceted enabling factors contributing to ORF susceptibility and victimisation. The model offers a structured means of identifying and thematising enabling factors across the micro-, meso-, exo-, macro-, and chrono-levels, thereby capturing the complex and multifaceted dimensions of ORF. The social-ecological framework facilitates interdisciplinarity and integrates insights from various research strands while maintaining coherence within the conceptual framework. Furthermore, in examining the complex, situational opportunities in the ecological environment of ORF, routine activity theory provides a theoretical framework for elucidating the opportunity structures associated with cyber-enabled fraud.

4. Methodological approach

This article provides an overview of ORF and the multifaceted factors, including risk and protective factors, that enable ORF susceptibility and victimisation, particularly in the Nordic and Norwegian contexts. The analysis highlights findings derived from both scholarly and grey literature, guided by the social-ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986; Stokols, 1996, 2018) and routine activity theory (Cohen & Felson, 1979). These frameworks inform a holistic approach to crime prevention. Accordingly, this article provides an exploratory and extensive overview of the phenomenon and enabling factors rather than serving as a scoping or systematic literature review of ORF, intimate partner violence, grooming, and online dating. Particular emphasis was placed on the relevance of enabling factors in the Nordic and Norwegian contexts, ensuring that the analysis remains attuned to region-specific conditions while preserving a holistic perspective.

The data supporting this analysis originate from two primary sources: 1) an original scoping review literature search (pre-registered scoping review (Feng Mikalsen et al., 2023, 22 May) concerning grooming in online dating romance frauds and scams, conducted collaboratively by two librarians (see Acknowledgements) and the author, and 2) supplementary searches conducted through snowballing, citation chaining, and ad hoc searching, performed by the author, in alignment with the objectives of this article.

The first primary source of data, the scholarly and grey literature from the scoping review, was derived from the databases, Criminal Justice Abstracts (EBSCO), EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, ProQuest Sociological Collection & Criminology Collection, Scopus, Web of Science, OAISTER, BASE, Oria and Google Scholar. A comprehensive description of the scoping review methodology, conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews) checklist (see, e.g., Tricco et al., 2018), along with the original keyword search strategy, is available in the research protocol on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/7t8c2).

Supplementary literature searches, which constitute the second primary source of data, were conducted as follows: Based on the original scoping review search, the author identified literature that delineates the similarities between online romance fraud and domestic violence, coercive control, and intimate partner violence (see, e.g., Carter, 2021; Cross et al., 2018). Following the identification of key literature concerning the similarities between ORF and intimate partner violence, the subsequent process was guided by the snowballing search method (Greenhalgh & Peacock, 2005). The author conducted supplementary searches based on the literature identified in the scoping review, using snowballing, citation chaining, and ad hoc searching. The supplementary searches provided a review of existing scholarly and grey literature encompassing various topics (e.g., domestic violence, coercive control, intimate partner violence, cyber-intimate partner violence, and technology-facilitated abuse). Additionally, key Nordic and Norwegian policing literature relevant to the study objectives was incorporated to enhance the discussion within a social-ecological framework. These findings collectively inform the objectives of this article.

The author conducted title and abstract screening in Covidence, followed by a full-text reading and preliminary coding of 141 records from the first primary data source, utilising NVivo software and EndNote. The inclusion criteria for the literature necessitated relevance to the objectives of this article (e.g., ORF or ORF and intimate partner violence). Studies that were excluded lacked explicit references to online dating romance frauds and scams, or primarily focused on specific types of exploitation in ORF (e.g., sextortion; see, e.g., Cross et al., 2023; Cross et al., 2022) or perceived threat (e.g., fear of crime; see, e.g., Cross & Lee, 2022). Additional inclusion criteria were that the publications provided insights into the factors and dynamics that contribute to ORF susceptibility and victimisation. The software programs facilitated the organisation of thematic categories, explicitly focusing on enabling factors at various levels within the social-ecological framework. For the supplementary data source, 31 records were read in full text and preliminarily coded, followed by a similar organisation of thematic categories in NVivo software and EndNote. Overall, the main emphasis was on literature that highlighted the factors and dynamics that contribute to ORF susceptibility and victimisation, as well as the interrelationships between victims and fraudsters, rather than on fraudsters’ perspectives. Only publications that offered insights relevant to the aforementioned objectives of this article were subsequently included in the analysis, which was guided by the social-ecological framework and routine activity theory.

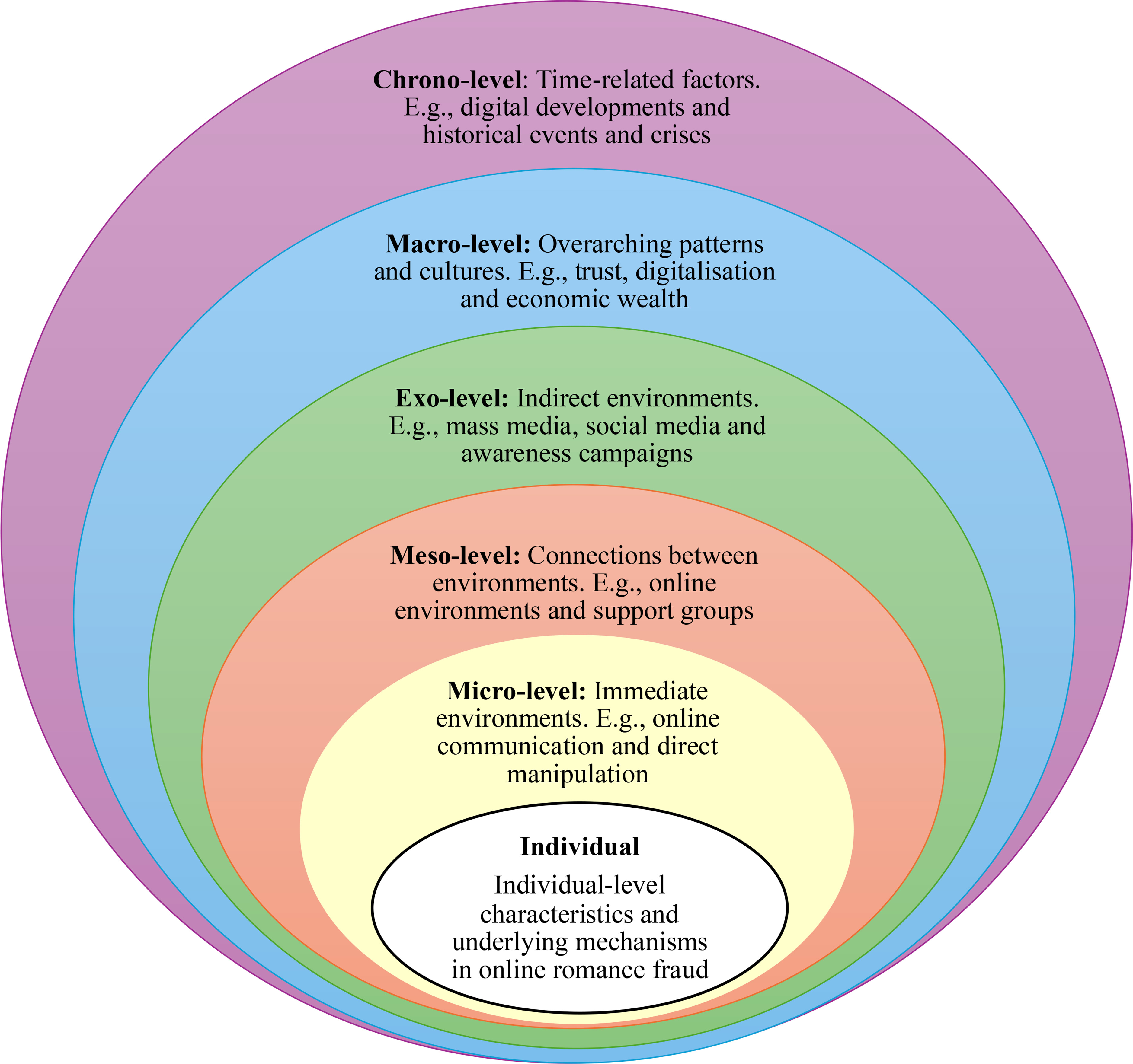

The scoping review search, complemented by snowballing, citation chaining, and ad hoc searches, resulted in the identification of 39 publications from both scholarly and grey literature, which were incorporated into the analysis within the social-ecological framework. The following analysis examines ORF and identifies enabling factors by highlighting literature that provides insights into the factors and dynamics contributing to ORF susceptibility and victimisation, especially within a Nordic and Norwegian context. Figure 1 illustrates the enabling factors.

Figure 1.

Social-ecological framework of online romance fraud

5. Enabling factors

5.1 Individual level

At the individual level, the enabling factors of ORF relate to increased risk and vulnerability through characteristics such as gender, age, socioeconomic status (SES), and social and psychological characteristics (Buchanan & Whitty, 2014; Lee et al., 2022; Sorell & Whitty, 2019; Whitty, 2018; Whitty & Buchanan, 2012b). Despite men and women being equally exposed to becoming ORF victims (Sorell & Whitty, 2019; Whitty, 2013b), most victims of ORF are middle-aged and female, seeking partners on dating sites (Sorell & Whitty, 2019; Whitty, 2018), highly educated, and have more disposable income than other groups (Lee et al., 2022; Whitty, 2018). Other characteristics, such as emotional vulnerabilities, including marital abuse, neglect, loneliness, and longing for affection and companionship, are deliberately targeted in the ORF (Aborisade et al., 2024; Buchanan & Whitty, 2014). As middle-aged and elderly individuals in Nordic societies report significant levels of loneliness, social exclusion, and isolation (Dahlberg et al., 2022), motivated offenders of ORF can exploit these vulnerabilities (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Consequently, middle-aged individuals with a higher SES in Nordic countries may be particularly susceptible to ORF.

5.2 Micro-level

The microsystem encompasses a pattern of activities, social roles, and interpersonal relationships encountered by a developing individual within a specific environment characterised by distinct physical and material features (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Relational behaviours identified in domestic violence and intimate partner violence research (Cruz, 2023; Shaari et al., 2019), such as coercive control and economic, psychological, and emotional abuse, are also applied in the context of ORF (see e.g., Carter, 2021; Cole, 2024; Cross et al., 2018). At the micro-level, within the closest environment of the individuals, fraudsters use techniques of grooming and persuasion to initiate contact, build trust, create intense bonds, deceive, and exploit in ORF (Cross et al., 2018; Dove, 2021), which show similarities with techniques applied in online child sexual exploitation and abuse (see, e.g., Cross, 2020; Whitty, 2013b; Whitty & Buchanan, 2012b). Considering the interactions between fraudsters and victims – including persuasive, psychological, and emotionally abusive techniques akin to the control and abusive dynamics in domestic violence, coercive control, and intimate partner violence – is essential for the prevention and mitigation of harm in ORF.

5.3 Meso-level

The mesosystem refers to the interrelations among two or more settings in which the developing individual actively participates (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). For adults, this includes interactions with partners, family, friends, work and work colleagues, social networks, and community settings (Ali & Rogers, 2023; Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Stokols, 1996). Acknowledging and fostering a sense of community among victims may play an essential role in the prevention, intervention, and aftermath of ORF, including preventing re-victimisation. In ORF cases, this may involve the existence of support groups and interactions with groups that can contribute to awareness and impede victimisation and re-victimisation. Examples of support group initiatives are the Finnish “Romance Scam Recovery Project”, and “Love Said”, a self-claimed “Fraud center and think thank”, established by prior victims of ORF and catfishing. The mission of the latter group is to “support victims of fraud through practical support, mental health support and education/training”. Despite these initiatives, which may enhance emotional and social well-being (Stokols, 1996), research on support groups for ORF victims remains limited, necessitating further research to determine their influence and impact on these support groups. One such study, however, indicated that while there are strong benefits, challenges arise from diverging individual expectations among victims of ORF (Cross, 2019).

5.4 Exo-level

The exosystem refers to one or more environments in which the individual is not an active participant, yet where events occur that affect, or are affected by, what occurs in the specific setting (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), such as health facilities, social services, and mass media. Prevention measures against ORF, including information, and public awareness campaigns from the police, online dating operators, mobile network operators, banks, and organisations on ORF, can serve to inform and educate the general population. Media portrayals and awareness campaigns of ORF and victims’ ORF experiences, along with research on media content, can enhance awareness of ORF and thus offer preventive insights and knowledge. The aim of media campaigns, as a primary victim-centred measure, is to increase general awareness and understanding of susceptibility (Lomell & Gundhus, 2024). Thus, it is important to inform potential victims about what they can and should do to protect themselves against crime. Mass media and social media may also affect the public’s perception and knowledge of ORF, and vice versa. The Norwegian television series Åsted Norge26. Norske kvinner kjærlighetssvindlet, pengene gikk til tørrfisk and Åsted Norge: 1. Professor kjærlighetssvindlet – TV 2 Play (accessed 05.11.2024). depicted a case involving a Norwegian professor defrauded of 13 million Norwegian kroner through ORF, which subsequently prompted increased media coverage and discussions concerning cybercrime and its ramifications. Another ORF case, which included Norwegian and Scandinavian victims, was featured in the British true-crime Netflix documentary The Tinder Swindler28. The Tinder Swindler portrayed three women including a Norwegian lady being swindled for millions of dollars through ORF. The TV series depicted a man pretending to be a rich, wealthy diamond mogul, scamming multiple women through dating apps (Tinder-svindleren (2022) – IMDb (accessed 05.11.2024)). (Berg et al., 2023), raising profound attention in both Norwegian and international news media. This case also sparked discussions on X through the hashtag #tinderswindler (Lokanan, 2023). Some scholars argue that the likelihood of scam success is reduced when individuals have prior awareness of scam schemes (Downs et al., 2006, as cited in Whitty & Buchanan, 2012a). Nevertheless, Jensen et al. (2024) showed that awareness campaigns using mass messaging and targeting bank customers have a limited impact on reducing financial fraud. Conversely, with the increased number of true crimes in books and crime media in streaming series and podcasts, the public’s interest in violent and dangerous perpetrators has increased, including the glamourisation of ORF through narratives and music artists (see, e.g., Lazarus et al., 2023).

5.5 Macro-level

The macrosystem refers to regularities in the structure and content of lower-order systems (micro-, meso-, and exo-) at the level of subcultures or broader culture, including any belief systems or ideologies that underpin these regularities (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). This includes interconnected systems characterised by “overarching patterns of ideology and organization of the social institutions common to a particular culture or subculture” (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 8), including intersocietal contrasts, such as those observed between different countries.

Social and institutional factors, along with environmental dimensions, also influence individuals’ susceptibility to cyberscams, particularly the ORF (Darem et al., 2024). This is illustrated in the following aspects related to trust, digitalisation, and the economy.

Trust, or the abuse of trust, constitutes a fundamental element in the dynamics of manipulation, placing individuals and countries at risk of ORF. Trust is an essential component of the anatomy of scams (Whitty, 2013a, 2013b). Individual trust levels may also stem from the collective cultural perceptions of trust at the societal level. Nordic welfare states are typically known for their high levels of institutional, interpersonal, general, and social trust, including comprehensive social safety nets (Delhey et al., 2011; Norwegian National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime (Økokrim), 2024; Pietilä & Korhonen, 2024; Van Vleet et al., 2021). A cross-national study of 60 nations that predicted levels of social trust found that Norway, Sweden, and Denmark had the highest levels of trust, and Finland and Iceland were close to this level (Delhey & Newton, 2005). Paradoxically, this context of high social trust may increase an individual’s susceptibility to ORF, as the population’s perceptions of honest correspondence with the state and neighbours may extend to assumptions about similarly trustworthy connections on social networking and online dating platforms. Arguably, inhabitants of these welfare states may be less inclined to question the persuasive and manipulative ORF processes, thereby facilitating the success of fraudulent requests. The cultural openness and high levels of trust in the Nordic countries can create a conducive environment for fraudulent activities, in which fraudsters perceive individuals as naïve, gullible, or uncritical (Whitty, 2018), making them suitable targets for ORF (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Recognising how societal trust can be exploited is essential to developing crime-prevention strategies that address trust-based vulnerabilities.

Digitalisation fosters new forms of communication, interaction, and social arenas, while simultaneously providing fraudsters with continuous access to suitable targets for committing ORF (Cohen & Felson, 1979). In accordance with the terminology of routine activity theory, Lomell and Gundhus (2024) argue that everyone in today’s digitalised society constitutes a suitable target for online fraud. New communication technologies facilitate anonymity in ORF, and “the anonymity which is de facto guaranteed online allows criminals to have total control over their self-representation” (Anesa, 2020), thereby enabling fraudsters to hide their true identities behind fabricated online profiles. Norway, recognised as one of the most digitalised societies worldwide, exhibits a high level of trust among individuals and corporations, making it an appealing and suitable target for cybercriminals (Cohen & Felson, 1979; National Criminal Investigation Service (KRIPOS), 2025).

Economic inequality is identified as a risk factor for ORF victimisation. The Nordic countries may be especially susceptible to economic exploitation because of their wealth and income equality (Delhey & Newton, 2005), as they are among the richest countries globally. Cybercriminals predominantly focus on and target wealthy, financially stable Westerners who are desperately looking for romantic relationships (Aborisade et al., 2024; Abubakari, 2024; Barnor et al., 2020; Lazarus et al., 2025). Due to the Norwegian economy and the population’s financial capacity, they are perceived as attractive targets for investment and romance scams (National Criminal Investigation Service (KRIPOS), 2024). The concept of Nordic exceptionalism, along with their developed economies, renders Nordic countries suitable targets for financial vulnerability and exploitation due to their monetary value (Cohen & Felson, 1979; Holt et al., 2018).

5.6 Chrono-level

The chronosystem refers to the impact of temporal changes and continuity on the development of the environments in which individuals reside (Bronfenbrenner, 1986). ORF and ORF victimisation can be associated with degrees of digitalisation – for example, through the expansion of the dating industry (Gillespie, 2017). Over time, the use of online dating platforms has increased, leading to a corresponding rise in the availability of suitable targets (Cohen & Felson, 1979) and the number of ORF victims (Alam, 2021; Bilz et al., 2023). In addition to enabling arenas of exploitation, historical events and crises can affect ORF and susceptibility to ORF. One example is the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to restrictions and reduced physical contact, individuals became more dependent on online platforms to seek romantic partners (Alam, 2021). Results indicate that ORF increased after the pandemic began (Buil-Gil & Zeng, 2021). The large share of the population partaking in online activities and the digitalisation of activities seem to contribute to the facilitation of new forms of communication, providing fraudsters with constant access to suitable targets (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Another example of how the emergence of a new digitalised tool impacts human activity is the use of artificial intelligence (AI). One of the most powerful forms of persuasion in conversations between fraudsters and victims is the use of deceptive language and fictitious profiles. For example, fraudsters have exploited AI-based technology and deepfakes to generate images in order to deceive ORF victims (Cross, 2022). Although AI offers “new avenues for detecting and mitigating cyber threats” (Darem et al., 2024, p. 36), it also entails significant risks and new vulnerabilities when fraudsters exploit the technologies to systematise deceptive talk (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway, 2025).

6. Discussion and concluding remarks

This article has offered a detailed description and examination of online romance fraud (ORF), drawing upon insights from research on abusive mechanisms associated with domestic violence, coercive control, and intimate partner violence. Utilising both scholarly and grey literature that elucidates the factors and dynamics that contribute to ORF susceptibility and victimisation, this article has situated its findings within the social-ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986; Stokols, 1996, 2018) and routine activity theory (Cohen & Felson, 1979). It has provided a holistic analysis of the multifaceted enabling factors, such as risk and protective factors, that influence ORF susceptibility and victimisation, with particular emphasis on the Nordic and Norwegian contexts.

In the context of a phenomenological understanding of ORF, as presented above, ORF should not be understood merely, or prevented solely, as financial fraud. Instead, it should be regarded as a hybrid form of cyber-enabled fraud and emotional and economic partner violence. ORF encompasses elements of relationship and trust fraud, romance fraud, investment fraud, and advance fee frauds (Maras & Ives, 2024). Furthermore, ORF involves financial/socioeconomic, psychological and psychosocial dimensions (Carter, 2021; Cross et al., 2018; Lazarus et al., 2022; Maras & Ives, 2024), encompassing both economic and non-economic impacts, alongside manipulative and abusive techniques.

The social-ecological model and social-ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; 1986; Stokols, 1996; 2018) offer a comprehensive approach for examining the interactive factors that both promote and inhibit ORF susceptibility and victimisation. While individual-level characteristics are associated with ORF susceptibility, the social-ecological framework expands this perspective by framing various enabling factors of ORF. It underscores the importance of interactions between different levels, including individuals, victims and fraudsters, victims and support groups, phenomenological knowledge disseminated through media and awareness campaigns, broader societal structures such as trust, digitalisation, global economic inequality and wealth, as well as time-related factors like digital development and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Existing research at the micro- and meso-levels indicates that specific individual-level characteristics are associated with ORF susceptibility and victimisation. These characteristics include being a highly educated, middle-aged woman seeking partners on dating sites (Whitty, 2018), and possessing more disposable income compared to other groups (Lee et al., 2022; Whitty, 2018). Research findings also reveal that fraudsters employ interpersonal, micro-level techniques to groom, build trust, manipulate, and exploit victims in ORF, which share commonalities with the dynamics of domestic violence, coercive control, and intimate partner violence (Carter, 2021; Cole, 2024; Cross et al., 2018), as well as online child sexual exploitation and abuse (Cross, 2020; Whitty, 2013b; Whitty & Buchanan, 2012b). Recognising that ORF extends beyond financial fraud, incorporating elements akin to other forms of abuse and exploitation, is imperative for enhancing the understanding of ORF and thereby strengthening preventive efforts and initiatives.

Similar to other social phenomena, such as gaslighting (Sebring, 2021; Sweet, 2019), ORF is deeply rooted in and influenced by broader societal and global structures, which are then converted into micro-level strategies of abuse, deception, manipulation, and fraud (see, e.g., Dove, 2021; Sweet, 2019). A comprehensive understanding of ORF necessitates an examination of its “cultural, structural and institutional contexts” (Sweet, 2019, p. 854), and considering an analysis of “the interlocking circles of ecological influence on individuals and their experience” (Campbell & Alhusen, 2011, p. 257). It is essential to consider the broader structures and systems, situating individuals and the hybrid form of cyber-enabled fraud within their environmental and contextual frameworks, including, e.g., human, social, cultural, digital and economic factors. By employing the proposed social-ecological framework, ORF prevention can be conceptualised along a continuum, with interventions directed at the micro-level focusing on individuals and macro-level efforts aimed at societal change (Pauls et al., 2017).

Future research should explore the significance of multilevel factors that enable ORF, including broader temporal macro-structures, which provide fertile ground and suitable targets for the effectiveness of cyber-enabled crime. As Aborisade (2022) notes, rather than relying solely on a two-dimensional victim–perpetrator model, research on this phenomenon could benefit from adopting a social-ecological perspective. Addressing hybrid cyber-enabled crimes through a social-ecological lens can enhance the efforts of researchers, police, policymakers, and other professionals to target specific levels, including individuals, groups, and societal and global structures, in order to better understand the relationships between these levels.

Professionals – particularly police – can play a critical role in preventing romance fraud, both offline and online, by intervening before, during, and after the occurrence of such crimes. In the context of preventing abuse in intimate partner violence/cyber-intimate partner violence and dating violence, the primary objective is to avert incidents before they start (Center for Disease Control, 2012). Therefore, it is imperative to enhance police understanding of the social manipulative processes involved in ORF in order to improve their response capabilities. Furthermore, a significant priority in the realm of intimate partner violence is to “better inform policy and collaborative action to keep individuals, families and communities safe” (Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police, 2016, p. 2). Drawing insights from intimate partner violence prevention efforts, valuable lessons can be learned from campaigns highlighting warning signs of intimate partner violence and available community resources (Keller & Honea, 2016). Given that ORF is a socially situated and context-bound social phenomenon, akin to intimate partner violence (Storer et al., 2021), preventive policing, and policing strategies should consider the importance of multilevel factors that enable ORF susceptibility and victimisation.

Fraud, particularly online fraud, has long been a low priority for police agencies worldwide, with insufficient resources allocated to address its severe impact (Button, 2012; Cross, 2016; Doig et al., 2001; Gannon & Doig, 2010). Interviews with police detectives working with an intervention model for victims of advance fee fraud revealed challenges in developing effective policing strategies to reduce the duration and severity of financial victimisation (Webster & Drew, 2017). Furthermore, Nordic police forces are considered to be lagging in technological development and failing to utilise received information for analytical purposes (Norwegian National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime (Økokrim), 2024). Norway, as one of the most digitalised societies globally, has a high level of trust among individuals and companies, rendering them attractive and suitable targets for cybercriminals (Cohen & Felson, 1979; National Criminal Investigation Service (KRIPOS), 2025). Despite prevention being the primary strategy of the police in Norway (National Police Directorate, 2018, 2020), the police’s information and knowledge of fraud remain insufficient (Norwegian National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime (Økokrim), 2023), which can impede prevention efforts (Ellefsen et al., 2023).

Effective crime prevention necessitates multiagency collaboration, which involves the participation of entities beyond the police (Sunde & Sunde, 2022). Facilitating such collaboration while implementing preventive strategies is crucial for mitigating and addressing criminal incidents, particularly ORF. The Norwegian National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime (Økokrim) (2023) has emphasised the importance of both law enforcement and the private sector in the digital contest between criminal actors and preventive efforts, which will significantly influence the Norwegian police’s management strategies. According to the Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway (2025), fraud scenarios in Nordic countries share numerous similarities, with banks operating across national borders within the region. Although banks in Nordic countries intercept a considerable proportion of fraud attempts, a notable number of fraudulent transactions remain undetected by their automated monitoring systems (Norwegian National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime (Økokrim), 2024). The success of comprehensive societal and police initiatives to combat fraud and money laundering remains, among other things, dependent on financial institutions’ capacity to develop effective detection indicators. Closer and more frequent collaboration among banks to enhance information sharing and cooperation within Nordic countries is recommended (Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway, 2025). With capable guardians against crime, the protection of potential ORF victims may become less complex, thereby reducing the necessity for stringent control measures (Cohen & Felson, 1979).

Cross et al. (2018) underscored the importance of fostering dialogue between research fields to enhance insights and knowledge within each field. This article advocates for recognising conceptual and empirical parallels between deceptive processes and manipulative techniques in the context of ORF, domestic violence, coercive control, and intimate partner violence, highlighting their significant impact on victims, their families, and communities. However, while there are overlaps in behaviours, manipulative techniques, and enabling factors, integrating concepts across fields may risk undermining prevention efforts by reducing specificity and relevance to target groups. For effective crime prevention, this article advocates for acknowledging the parallels across various types of abuse and cybercrimes while ensuring the precision of well-established concepts.

Recognising the intricate interplay of factors associated with ORF is crucial, as is fostering discourse on incorporating a holistic approach within a social-ecological framework to examine a hybrid form of cyber-enabled fraud. Drawing inspiration from Cross et al. (2015) and Cole (2024), it is imperative to empirically investigate these initial conceptualisations of ORF to advance the proposed enabling factors and, ultimately, to develop effective preventive intervention strategies. A social-ecological framework offers a valuable approach for assisting police, law enforcement agencies, financial systems and banks, dating services, health systems, social workers, and academic institutions in achieving a more comprehensive understanding of the complexity of hybrid cyber-enabled fraud, ORF, and the enabling factors arising from various levels and social systems. This article proposes a multilevel approach, providing a starting point for a deeper understanding, further research, and prevention of ORF by exploring parallels across abuse, violence, and other forms of cyber-enabled fraud while emphasising the importance of maintaining the clarity of established concepts.

The intersection of Nordic welfare states, independence, and individual social and emotional needs warrants increased attention in the context of preventive measures against hybrid and deceptive cyber-enabled fraud. Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of the individual, interpersonal, and structural dimensions and enabling factors influencing ORF susceptibility and victimisation is essential for developing more effective crime prevention, proactive policing strategies, and public awareness campaigns. This article illustrates the complexity of ORF, emphasising the necessity of addressing and preventing this phenomenon through a holistic framework. While acknowledging this, ORF is conceptualised as a hybrid cyber-enabled fraud and emotional and economic partner violence that systematically manipulates trust over time, targeting individuals perceived as wealthy, lonely, and seeking romantic connections and love.

Acknowledgements

I greatly appreciate the support of my PhD supervisor, Brita Bjørkelo, for initiating the idea for this paper as well as for the input and discussions throughout the process. I wish to express my gratitude to the librarians Glenn Karlsen Bjerkenes (University of Oslo), for conducting the initial scholarly database searches, and Kjersti Dahlskås Urnes (Norwegian Police University College), for undertaking the initial grey literature searches associated with the original scoping review on grooming in online dating romance frauds and scams. The author would also like to thank several researchers, colleagues, the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments at various stages of the manuscript preparation.

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Content

During the preparation of this article, the author utilised Paperpal, Grammarly, and ChatGPT to enhance the language and readability. After employing these tools and services, the author reviewed and revised the content as necessary and takes full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Funding

This work is funded by the Norwegian Police University College with support from the Ministry of Justice and Public Security / the National Police Directorate in Norway, as part of the author’s PhD project. There are no other relevant financial or non-financial interests, directly or indirectly related to this work, to disclose.

References

-

Aborisade, R.A. (2022). Internet Scamming and the Techniques of Neutralization: Parents’ Excuses and Justifications for Children’s Involvement in Online Dating Fraud in Nigeria.

International Annals of Criminology

, 60 (2), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1017/cri.2022.13 -

Aborisade, R.A.,Ocheja, A.&Okuneye, B.A. (2024). Emotional and financial costs of online dating scam: A phenomenological narrative of the experiences of victims of Nigerian romance fraudsters.

Journal of Economic Criminology

, 3 , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconc.2023.100044 -

Abubakari, Y. (2024). Modelling the modus operandi of online romance fraud: Perspectives of online romance fraudsters.

Journal of Economic Criminology

, 6 , 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconc.2024.100112 -

Alam, M.N. (2021). Three Essays on Socially Engineered Attacks: The Case of Online Romantic Scams.

[PhD dissertation, The University of North Carolina]

. -

Ali, P.&Rogers, M.M. (2023). Theorising Gender-Based Violence. InP. Ali&M.M. Rogers(eds.),

Gender-Based Violence: A Comprehensive Guide

. (1 ed., pp. 17–36).Springer International Publishing AG

. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05640-6 -

Anesa, P. (2020). Lovextortion: Persuasion strategies in romance cybercrime.

Discourse, Context & Media

, 35 , 100398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2020.100398 -

Bailey, J.S. (2021).

The Emerald International Handbook of Technology-Facilitated Violence and Abuse

.Emerald Publishing Limited

. -

Barnor, J.N.B.,Boateng, R.,Kolog, E.A.&Afful-Dadzie, A. (2020). Rationalizing Online Romance Fraud: In the Eyes of the Offender. Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS) 2020 Proceedings. 21. https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2020/info_security_privacy/info_security_privacy/21/?utm_source=aisel.aisnet.org%2Famcis2020%2Finfo_security_privacy%2Finfo_security_privacy%2F21&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages

-

Berg, S.,Thorvik, T.G.&Meland, P.H. (2023). Fool Me Once, Shame on Me – A Qualitative Interview Study of Social Engineering Victims. 1–21. https://www.ntnu.no/ojs/index.php/nikt/article/view/5644/5090

-

Bilz, A.,Shepherd, L.A.&Johnson, G.I. (2023). Tainted Love: a Systematic Literature Review of Online Romance Scam Research.

Interacting with Computers

, 35 (6), 773–788. https://doi.org/10.1093/iwc/iwad048 -

Bjørgo, T. (2016).

Preventing Crime : A Holistic Approach

.Palgrave Macmillan

. -

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979).

The Ecology of Human Development. Experiments by Nature and Design

.Harvard University Press

. -

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the Family as a Context for Human Development: Research Perspectives.

Developmental Psychology

, 22 (6), 723–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723 -

Buchanan, T.&Whitty, M.T. (2014). The online dating romance scam: causes and consequences of victimhood.

Psychology, Crime & Law

, 20 (3), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2013.772180 -

Buil-Gil, D.&Zeng, Y. (2021). Meeting you was a fake: investigating the increase in romance fraud during COVID-19.

Journal of Financial Crime

, 29 (2), 460–475. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-02-2021-0042 -

Button, M. (2012). Cross‐border fraud and the case for an “Interfraud”.

Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management

, 35 (2), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639511211230057 -

Campbell, J.C.&Alhusen, J.D. (2011). Vulnerability and protective factors for intimate partner violence. InJ.W. White,M.P. Koss&A.E. Kazdin(eds.),

Violence Against Women and Children, Volume 1: Mapping the Terrain

. (Vol. 1., 1st ed., pp. 243–263).American Psychological Association

. https://doi.org/10.1037/12307-011 -

Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police . (2016). National Framework for Collaborative Police Action on Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). https://www.cacp.ca/_Library/resources/National_Framework_for_Collaborative_Police_Action_on_Intimate_Partner_Violence_-_March_2016.pdf

-

Carter, E. (2021). Distort, Extort, Deceive and Exploit: Exploring the Inner Workings of a Romance Fraud.

The British Journal of Criminology

, 61 (2), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azaa072 -

Center for Disease Control . (2012). Understanding teen dating violence: Fact sheet. https://www.uis.edu/sites/default/files/inline-images/Understanding%20Teen%20Dating%20Violence_%202012%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf

-

Chethiyar, S.D.M.,Vedamanikam, M.,Sameem, M.&Muniandy, V.D. (2021). Losing The War Against Money Mule Recruitment: Persuasive Technique In Romance Scam.

Ilkogretim Online – Elementary Education Online

, 20 (3), 2569–2585. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Assc-Prof-Dr-Saralah-Chethiyar/publication/363363843_Losing_The_War_Against_Money_Mule_Recruitment_Persuasive_Technique_In_Romance_Scam_Losing_The_War_Against_Money_Mule_Recruitment_Persuasive_Technique_In_Romance_Scam/links/6319649b071ea12e3618c3e3/Losing-The-War-Against-Money-Mule-Recruitment-Persuasive-Technique-In-Romance-Scam-Losing-The-War-Against-Money-Mule-Recruitment-Persuasive-Technique-In-Romance-Scam.pdf -

Chuang, J.-Y. (2021). Romance Scams: Romantic Imagery and Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation.

Frontiers in Psychiatry

, 12 , 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.738874 -

Clevenger, S.&Gilliam, M. (2020). Intimate Partner Violence and the Internet: Perspectives. InT. Holt&A.M. Bossler(eds.),

The Palgrave Handbook of International Cybercrime and Cyberdeviance

. (pp. 1333–1352).Palgrave Macmillan

. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78440-3_58 -

Cohen, L.E.&Felson, M. (1979). Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach.

American Sociological Review

, 44 (4), 588. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094589 -

Cole, R. (2024). A qualitative investigation of the emotional, physiological, financial, and legal consequences of online romance scams in the United States.

Journal of Economic Criminology

, 6 , 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconc.2024.100108 -

Cross, C. (2016). Using financial intelligence to target online fraud victimisation: applying a tertiary prevention perspective.

Criminal Justice Studies

, 29 (2), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478601X.2016.1170278 -

Cross, C. (2019). “You’re not alone”: the use of peer support groups for fraud victims.

Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment

, 29 (5), 672–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2019.1590279 -

Cross, C. (2020). Romance Fraud. InT. Holt&A. Bossler(eds.),

The Palgrave Handbook of International Cybercrime and Cyberdeviance

. (pp. 917–938).Palgrave Macmillan

. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78440-3 -

Cross, C. (2022). Using artificial intelligence (AI) and deepfakes to deceive victims: the need to rethink current romance fraud prevention messaging.

Crime Prevention and Community Safety

, 24 (1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-021-00134-w -

Cross, C. (2024). Romance baiting, cryptorom and ‘pig butchering’: an evolutionary step in romance fraud.

Current Issues in Criminal Justice

, 36 (3), 334–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2023.2248670 -

Cross, C.&Layt, R. (2022). “I Suspect That the Pictures Are Stolen”: Romance Fraud, Identity Crime, and Responding to Suspicions of Inauthentic Identities.

Social Science Computer Review

, 40 (4), 955–973. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439321999311 -

Cross, C.&Lee, M. (2022). Exploring Fear of Crime for Those Targeted by Romance Fraud.

Victims & Offenders

, 17 (5), 735–755. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2021.2018080 -

Cross, C.,Dragiewicz, M.&Richards, K. (2018). Understanding Romance Fraud: Insights From Domestic Violence Research.

The British Journal of Criminology

, 58 (6), 1303–1322. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azy005 -

Cross, C.,Holt, K.&O’Malley, R.L. (2022). “If U Don’t Pay they will Share the Pics”: Exploring Sextortion in the Context of Romance Fraud.

Victims & Offenders

, 18 (7), 1194–1215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2022.2075064 -

Cross, C.,Holt, K.&Holt, T.J. (2023). To pay or not to pay: An exploratory analysis of sextortion in the context of romance fraud.

Criminology & Criminal Justice

, 25 (3), 777–792. https://doi.org/10.1177/17488958221149581 -

Cross, D.,Barnes, A.,Papageorgiou, A.,Hadwen, K.,Hearn, L.&Lester, L. (2015). A social–ecological framework for understanding and reducing cyberbullying behaviours.

Aggression and Violent Behavior

, 23 , 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.016 -

Cruz, D. (2023).

Developmental Trauma : Theory, Research and Practice

.Routledge

. -

Cullen, F.T.,Agnew, R.&Wilcox, P. (2014).

Criminological Theory : Past to Present : Essential Readings

. (5th ed).Oxford University Press

. -

Dahlberg, L.,McKee, K.J.,Lennartsson, C.&Rehnberg, J. (2022). A social exclusion perspective on loneliness in older adults in the Nordic countries.

European Journal of Ageing

, 19 (2), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-022-00692-4 -

Darem, A.,Alhashmi, A.,Sheatah, H.K.,Mohamed, I.B.,Jabnoun, C.,Allan, F.M.,Dhibi, A.&Elmourssi, D.M. (2024). Decoding the Deception: A Comprehensive Analysis of Cyber Scam Vulnerability Factors.

Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applied Data Science

, 2 (1). https://jisads.com/index.php/1/article/view/19/22 -

Delhey, J.&Newton, K. (2005). Predicting Cross-National Levels of Social Trust: Global Pattern or Nordic Exceptionalism?

European Sociological Review

, 21 (4), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jci022 -

Delhey, J.,Newton, K.&Welzel, C. (2011). How General Is Trust in “Most People”? Solving the Radius of Trust Problem.

American Sociological Review

, 76 (5), 786–807. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411420817 -

Doig, A.,Johnson, S.&Levi, M. (2001). New Public Management, Old Populism and the Policing of Fraud.

Public Policy and Administration

, 16 (1), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/095207670101600106 -

Dove, M. (2021).

The Psychology of Fraud, Persuasion and Scam Techniques : Understanding What Makes us Vulnerable

.Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group

. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003015994 -

Ellefsen, H.B.,Bjørkelo, B.,Sunde, I.M.&Fyfe, N.R. (2023). Unpacking preventive policing: Towards a holistic framework.

International Journal of Police Science & Management

, 25 (2), 196–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/14613557231163403 -

Feng Mikalsen, M.,Bjørkelo, B.,Bjerkenes, G.K.&Urnes, K.D. (2023, 22 May). Pre-registration of “Grooming in Online Dating Romance Frauds and Scams: A Scoping Review” [Pre-registration].

Open Science Framework

. https://osf.io/7t8c2 -

Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway . (2025). Risiko- og sårbarhetsanalyse (ROS) 2025. https://www.finanstilsynet.no/nyhetsarkiv/nyheter/2025/risiko--og-sarbarhetsanalyse-ros-2025/

-

Flynn, A.,Powell, A.&Hindes, S. (2024). An Intersectional Analysis of Technology-Facilitated Abuse: Prevalence, Experiences and Impacts of Victimization.

The British Journal of Criminology

, 64 (3), 600–619. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azad044 -

Gannon, R.&Doig, A. (2010). Ducking the answer? Fraud strategies and police resources.

Policing and Society

, 20 (1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439460903377329 -

Gillespie, A.A. (2002). Child protection on the internet – challenges for criminal law.

Child and Family Law Quarterly

, 14 (4), 411–426. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2084816 -

Gillespie, A.A. (2017). The Electronic Spanish Prisoner: Romance Frauds on the Internet.

The Journal of Criminal Law

, 81 (3), 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022018317702803 -

Greenhalgh, T.&Peacock, R. (2005). Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources.

BMJ

, 331 (7524), 1064–1065. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68 -

Holt, T.J.,Bossler, A.M.&Seigfried-Spellar, K.C. (2018).

Cybercrime and Digital Forensics : An Introduction

. (2nd ed).Routledge

. -

Jensen, R.I.T.,Gerlings, J.&Ferwerda, J. (2024). Do Awareness Campaigns Reduce Financial Fraud?.

European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research

. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-024-09573-1 -

Keller, S.N.&Honea, J.C. (2016). Navigating the gender minefield: An IPV prevention campaign sheds light on the gender gap.

Global Public Health

, 11 (1–2), 184–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1036765 -

Koon, T.H.&Yoong, D. (2013). Preying on lonely hearts: A systematic deconstruction of an internet romance scammer‘s online lover persona.

Journal of Modern Languages

, 23 , 28–40. http://ijie.um.edu.my/index.php/JML/article/view/3288 -

Kopp, C.,Sillitoe, J.,Gondal, I.&Layton, R. (2016). Online Romance Scam: Expensive e-Living for romantic happiness. BLED 2016 Proceedings, 36. http://aisel.aisnet.org/bled2016/36

-

Koukopoulos, N.,Janickyj, M.&Tanczer, L.M. (2025). Defining and Conceptualizing Technology-Facilitated Abuse (“Tech Abuse”): Findings of a Global Delphi Study.

Journal of Interpersonal Violence

, 41 (1–2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605241310465 -

Lazarus, S.,Button, M.&Kapend, R. (2022). Exploring the value of feminist theory in understanding digital crimes: Gender and cybercrime types.

The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice

, 61 (3), 381–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/hojo.12485 -

Lazarus, S.,Whittaker, J.M.,McGuire, M.R.&Platt, L. (2023). What Do We Know About Online Romance Fraud Studies? A Systematic Review of the Empirical Literature (2000 to 2021).

Journal of Economic Criminology

, 2 , 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconc.2023.100013 -

Lazarus, S.,Hughes, M.,Button, M.&Garba, K.H. (2025). Fraud as Legitimate Retribution for Colonial Injustice: Neutralization Techniques in Interviews with Police and Online Romance Fraud Offenders.

Deviant Behavior

, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2024.2446328 -

Lazarus, S.,Olaigbe, O.,Adeduntan, A.,Dibiana, E.T.&Okolorie, G.U. (2023). Cheques or dating scams? Online fraud themes in hip-hop songs across popular music apps.

Journal of Economic Criminology

, 2 , 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconc.2023.100033 -

Lee, K.-F.,Chan, M.Y.&Mohamad Ali, A. (2022). Self and desired partner descriptions in the online romance scam: a linguistic analysis of scammer and general user profiles on online dating portals.

Crime Prevention and Community Safety

, 25 (1), 20–46. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-022-00169-7 -

Lokanan, M.E. (2023). The tinder swindler: Analyzing public sentiments of romance fraud using machine learning and artificial intelligence.

Journal of Economic Criminology

, 2 , 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconc.2023.100023 -

Lomell, H.M.&Gundhus, H.O.I. (2024).

Kriminalitetsforebygging: teorier og praksiser

.Universitetsforlaget

. -

Maras, M.-H.&Ives, E.R. (2024). Deconstructing a form of hybrid investment fraud: Examining ‘pig butchering’ in the United States.

Journal of Economic Criminology

, 5 , 100066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconc.2024.100066 -

Mæland, K.B. (2018). Tove ble lurt for 380.000 kroner i dating-svindel. Nettavisen. https://www.nettavisen.no/nyheter/innenriks/tove-ble-lurt-for-380-000-kroner-i-dating-svindel/s/12-95-3423485864

-

National Criminal Investigation Service (KRIPOS) . (2024). Cyberkriminalitet 2024. Politiets årlige rapport om cyberrettet og cyberstøttet kriminalitet. https://www.politiet.no/globalassets/tall-og-fakta/datakriminalitet/cyberkriminalitet-2024.pdf

-

National Criminal Investigation Service (KRIPOS) . (2025). Cyberkriminalitet 2025 Politiets årlige rapport om cyberrettet og cyberstøttet kriminalitet. https://www.politiet.no/globalassets/tall-og-fakta/datakriminalitet/cyberkriminalitet-2025.pdf

-

National Library of Medicine . (2025). 3. Health Data Sources: (Other) Grey Literature. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/oet/ed/stats/03-600.html

-

National Police Directorate . (2018). Kriminalitetsforebygging som politiets primærstrategi 2018 – 2020. Politiet mot 2025 - delstrategi. https://www.politiet.no/globalassets/05-om-oss/03-strategier-og-planer/kriminalitetsforebygging-politiets-primarstrategi.pdf

-

National Police Directorate . (2020). I forkant av kriminaliteten. Forebygging som politiets hovedstrategi (2021-2025). https://www.politiet.no/globalassets/05-om-oss/03-strategier-og-planer/i-forkant-av-kriminaliteten.pdf

-

Newburn, T. (2017).

Criminology

. (3rd ed).Routledge

. -

Norwegian National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime (Økokrim) . (2023). Årsrapport 2023. https://img8.custompublish.com/getfile.php/5295597.2528.7bqmlmtiqjmkwk/%C3%98kokrim%2B%E2%80%93%2Ba%CC%8Arsrapport%2B2023-nett.pdf?return=www.okokrim.no

-

Norwegian National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime (Økokrim) . (2024).

Nordic threat assessment on online fraud 2024

. https://polisen.se/siteassets/dokument/ovriga_rapporter/nordic-threat-assessment-on-online-fraud-2024-web.pdf/download/?v=46fb9ca8b5e21460a8a232a324b64254 -

Offei, M.,Andoh-Baidoo, F.K.,Ayaburi, E.W.&Asamoah, D. (2022). How Do Individuals Justify and Rationalize their Criminal Behaviors in Online Romance Fraud?.

Information Systems Frontiers

, 24 (2), 475–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-020-10051-2 -

Pandey, M. (2023).

International Perspectives on Gender-Based Violence

. (1. ed. ).Springer International Publishing AG

. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-42867-8 -

Pauls, M.,Warthe, D.G.&Winterdyk, J.A. (2017). Preventing Domestic Violence: An International Overview. InJ.A. Winterdyk(ed.),

Crime Prevention : International Perspectives, Issues, and Trends

. (pp. 115–146).CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group

. -

Pietilä, E.&Korhonen, H. (2024). The harsh realities of romance scams. https://nordicwelfare.org/popnad/en/artiklar/the-harsh-realities-of-romance-scams/

-

Pratt, T.C.&Turanovic, J.J. (2016). Lifestyle and Routine Activity Theories Revisited: The Importance of “Risk” to the Study of Victimization.

Victims & Offenders

, 11 (3), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2015.1057351 -

Rege, A. (2009). What’s Love Got to Do with It? Exploring Online Dating Scams and Identity Fraud.

International Journal of Cyber Criminology

, 3 (2), 494–512. -

Robinson, A.&Myhill, A. (2021). Coercive control . IJ. Devaney,C. Bradbury-Jones,R.J. Macy,C. Øverlien&S. Holt(Red.),

The routledge international handbook of domestic violence and abuse

. (1. utg.s. 387–402).Routledge

. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429331053-29 -

Sebring, J.C.H. (2021). Towards a sociological understanding of medical gaslighting in western health care.

Sociology of Health & Illness

, 43 (9), 1951–1964. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13367 -

Shaari, A.H.,Kamaluddin, M.R.,Paizi@Fauzi, W.F.P.&Mohd, M. (2019). Online-Dating Romance Scam in Malaysia: An Analysis of Online Conversations between Scammers and Victims.

GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies

, 19 (1), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.17576/gema-2019-1901-06 -

Sorell, T.&Whitty, M. (2019). Online romance scams and victimhood.

Security Journal

, 32 (3), 342–361. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-019-00166-w -

Stokols, D. (1996). Translating Social Ecological Theory into Guidelines for Community Health Promotion.

American Journal of Health Promotion

, 10 (4), 282–298. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282 -

Stokols, D. (2018). Social Ecology in the Digital Age. Solving Complex Problems in a Globalized World.

Elsevier Academic Press

. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2014-0-04300-6 -

Storer, H.L.,Rodriguez, M.&Franklin, R. (2021). “Leaving Was a Process, Not an Event”: The Lived Experience of Dating and Domestic Violence in 140 Characters.

Journal of Interpersonal Violence

, 36 (11–12), NP6553–NP6580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518816325 -

Sunde, I.M.&Sunde, N. (2022). Conceptualizing an AI-based Police Robot for Preventing Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse: Part 2 – Legal Analysis of PrevBOT.

Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing

, 9 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.18261/njsp.9.1.11 -

Sweet, P.L. (2019). The Sociology of Gaslighting.

American Sociological Review

, 84 (5), 851–875. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419874843 -

Tanczer, L.M. (2023). Technology-Facilitated Abuse and the Internet of Things (IoT): The Implication of Smart, Internet-Connected Devices on Domestic Violence and Abuse. InB. Harris&D. Woodlock(eds.),

Technology and Domestic and Family Violence: Victimisation, Perpetration and Responses

. (pp. 76–87).Routledge

. -

Tricco, A.C.,Lillie, E.,Zarin, W.,O’Brien, K.K.,Colquhoun, H.,Levac, D.,Moher, D.,Peters, M.D.J.,Horsley, T.,Weeks, L.,Hempel, S.,Akl, E.A.,Chang, C.,McGowan, J.,Stewart, L.,Hartling, L.,Aldcroft, A.,Wilson, M.G.,Garritty, C., …Straus, S.E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation.

Annals of Internal Medicine

, 169 (7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850 -

Van Vleet, S.,Cummins, P.&Helsinger, A. (2021). Social Trust, Literacy, and Lifelong Learning: A Comparison of the U.S. and Nordic Countries.

Innovation in Aging

, 5 (Supplement_1), 762–762. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igab046.2823 -

Wang, F. (2024). Victim-offender overlap: the identity transformations experienced by trafficked Chinese workers escaping from pig-butchering scam syndicate.

Trends in Organized Crime

, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-024-09525-5 -

Wang, F.&Topalli, V. (2022). Understanding Romance Scammers Through the Lens of Their Victims: Qualitative Modeling of Risk and Protective Factors in the Online Context.

American Journal of Criminal Justice

, 49 (1), 145–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-022-09706-4 -

Wang, F.&Zhou, X. (2022). Persuasive Schemes for Financial Exploitation in Online Romance Scam: An Anatomy on Sha Zhu Pan (杀猪盘) in China.

Victims & Offenders

, 18 (5), 915–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2022.2051109 -

Wang, F.&Topalli, V. (2024). The cyber-industrialization of catfishing and romance fraud.

Computers in Human Behavior

, 154 , 108133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.108133 -

Wang, F.,Howell, C.J.,Maimon, D.&Jacques, S. (2021). The Restrictive Deterrent Effect of Warning Messages Sent to Active Romance Fraudsters: An Experimental Approach.

International Journal of Cyber Criminology

, 15 (1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4766529 -

Webster, J.&Drew, J.M. (2017). Policing advance fee fraud (AFF): Experiences of fraud detectives using a victim-focused approach.

International Journal of Police Science & Management

, 19 (1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355716681810 -

Whittaker, J.M.,Lazarus, S.&Corcoran, T. (2024). Are fraud victims nothing more than animals? Critiquing the propagation of “pig butchering” (Sha Zhu Pan, 杀猪盘).

Journal of Economic Criminology

, 3 , 100052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconc.2024.100052 -

Whitty, M.T. (2013a). Anatomy of the online dating romance scam.

Security Journal

, 28 (4), 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2012.57 -

Whitty, M.T. (2013b). The Scammers Persuasive Techniques Model. Development of a Stage Model to Explain the Online Dating Romance Scam.

The British Journal of Criminology

, 53 (4), 665–684. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azt009 -

Whitty, M.&Joinson, A. (2009).

Truth, Lies and Trust On The Internet

.Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group

. -

Whitty, M.T.&Buchanan, T. (2012a). The Online Romance Scam: A Serious Cybercrime.

Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking

, 15 (3), 181–183. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0352 -

Whitty, M.T.&Buchanan, T. (2012b). The Psychology of the Online Dating Romance Scam. https://fido.nrk.no/d6f57fd73b9898b42c8c322c961c8255f370677fbac5272b71d86047a5359b66/Whitty_romance_scam_report.pdf

-

Whitty, M.T.&Buchanan, T. (2016). The online dating romance scam: The psychological impact on victims – both financial and non-financial.

Criminology & Criminal Justice

, 16 (2), 176–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895815603773 -

Whitty, M.T. (2018). Do You Love Me? Psychological Characteristics of Romance Scam Victims.

Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking

, 21 (2), 105–109. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0729 -

Yar, M. (2005). The Novelty of ‘Cybercrime’: An Assessment in Light of Routine Activity Theory.

European Journal of Criminology

, 2 (4), 407–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/147737080556056

- 1Cyber-enabled fraud refers to illegal acts that uses information and communication technology (ICT), resulting in a loss of property (Maras & Ives, 2024)

- 2Domestic violence pertains to “a pattern of coercive and controlling behaviour that comprised some combination of physical, sexual and psychological forms of abuse directed at a current or former intimate partner.” (Cross et al., 2018, p. 1307).

- 3Coercive control refers to “a strategic course of oppressive conduct” intended to “intimidate, degrade, isolate, and control victims” (Stark, 2012, p. 18, as cited in Robinson & Myhill, 2021, p. 388)

- 4Intimate partner violence (IPV) refers to behaviours and actions that “have the intent to harm an individual physically, sexually, emotionally or psychologically, and/or financially.” (Clevenger & Gilliam, 2020, p. 1335). Fundamental aspects of IPV are to exert control, create dependence and social isolation, as well as to hinder the victim’s exposure and perception of reality (Clevenger & Gilliam, 2020, p. 1336).

- 5See, e.g., Swedish women warned off dating ‘US men’ online – The Local, Outsmart a catfish to protect yourself from romance scams and from being the middleman in a money laundering scheme – LinkedIn, What are some online scammers working in Norway? – Quora and Tinder Swindler: the global cyber crime of ‘romance fraud’ – World Economic Forum (all accessed 06.11.2024).

- 6Grey literature is defined as “information produced on all levels of government, academia, business and industry in electronic and print formats not controlled by commercial publishing i.e., where publishing is not the primary activity of the producing body.” (National Library of Medicine 2025).

- 7Holistic refers to “relating to or concerned with wholes or with complete systems rather than with the analysis of, treatment of, or dissection into parts” HOLISTIC Definition & Meaning – Merriam-Webster (accessed 07.10.2024). As opposed to a narrow approach, a holistic crime-prevention approach puts efforts into more than one single or limited range of mechanisms and measures (Bjørgo, 2016, p. 6).

- 8Also: romance fraud (Carter, 2021; Cross, 2020), online romance scams (Anesa, 2020; Kopp et al., 2016), online dating romance scams (Azianura Hani et al., 2019; Buchanan & Whitty, 2014; Whitty, 2013b), online romance fraud (Bilz et al., 2023), internet romance scams (Koon & Yoong, 2013), sweetheart scams (Whitty, 2018), and sweetheart swindles (Rege, 2009).

- 9Grooming is usually described as a process where a child “is befriended by a would-be abuser in an attempt to gain the child’s confidence and trust, enabling them to get the child to acquiesce to abusive activity.” (Gillespie, 2002, p. 411).

- 10An advanced fee fraud (AFF) constitutes a type of scam that persuades individuals to make payments in advance for goods, services or financial benefits. This category of fraud includes a wide range of deceptive practices, from “dishonest sellers to the classic 419 scams operated by Nigerian gangs which promise a share of a greater fortune for the cost of a small service charge” (Clough, 2016, as cited in Gillespie, 2017, p. 218). AFF includes “an offender using deceit to secure a benefit from the victim (usually financial) with the promise of a future ‘pay-off’ for the victim” (Whitty & Buchanan, 2012, as cited in Webster & Drew, 2017, p. 39).

- 11Social ecology refers to “an overarching framework or set of theoretical principles for understanding the interrelations among diverse personal and environmental factors in human health and illness.” (Stokols, 1996, p. 283).

- 12For example, in the field of gender-based violence (see, e.g., Ali & Rogers, 2023; Pandey, 2023), domestic violence and abuse in general (Ali & Rogers, 2023), as well as violence and sexual abuse, and other forms of criminal behaviour (Stokols, 2018, as cited in Ellefsen et al., 2023).

- 13RAT is considered an “opportunity theory” that focuses on how “opportunities affect decision making by actual or potential offenders and how such opportunities can be manipulated so as to reduce or prevent crime” (Newburn, 2017, p. 170).

- 14For example, cyberharassment, cyberstalking, sextortion, revenge pornography, as well as social engineering and identity theft (Clevenger & Gilliam, 2020, p. 1334).

- 15Technology-facilitated abuse (TFA) describes “how technical systems are used to harass or control individuals” (Tanczer, 2023, p. 76). TFA involves the misuse of digital technologies to harass, coerce, threaten, abuse, or perform interpersonal violence (see e.g., Bailey, 2021; Flynn et al., 2024; Koukopoulos et al., 2025).

- 16Twenty-four publications (62%) were derived from the first primary source of data (scoping review literature searches), and 15 publications (38%) were included from the second primary source of data (supplementary literature searches).

- 17For example education, occupation, income, being a professional (Whitty & Joinson 2009).

- 18For a child, this concerns relations at home, schools, and neighbourhood peer groups (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p. 25).

- 19LoveSaid - About Us (accessed 17.05.2025).

- 20The term stems from the documentary “Catfish”, which investigated online deception, where an individual “creates a bogus virtual persona (complete with fake photos, videos, and a phony identity and backstory) to trick others into forming an emotional connection with them.” (Wang & Topalli, 2024, p. 2).

- 21LoveSaid – About Us (accessed 17.05.2025).

- 22Beskytt deg mot svindel og ID-tyveri – Politiet.no (accessed 28.04.2025).

- 23From a dating service: Kjærlighetssvindel (accessed 28.04.2025).

- 24From Norway: Hva er kjærlighetssvindel? (accessed 28.04.2025).

- 25From Norwegian banks: Hjertesorg og tomme lommebøker: Sånn avslører du kjærlighetssvindel – Nordea and

- 26

- 27Den anerkjente professoren ble kjærlighetssvindlet for hele 13. millioner kroner (accessed 05.11.2024).

- 28The Tinder Swindler portrayed three women including a Norwegian lady being swindled for millions of dollars through ORF. The TV series depicted a man pretending to be a rich, wealthy diamond mogul, scamming multiple women through dating apps (Tinder-svindleren (2022) – IMDb (accessed 05.11.2024)).

- 29The Tinder Swindler (accessed 05.11.2024).

- 30Former Twitter.

- 31The bank customers were over 40 years of age.

- 32Glamorising violent offenders with ‘true crime’ shows and podcasts needs to stop (accessed 30.05.2025).

- 33Social trust, defined as “the belief that others will not deliberately or knowingly do us harm, if they can avoid it, and will look after our interests, if this is possible” (Delhey & Newton, 2005).

- 34The harsh realities of romance scams – NVC (accessed 08.12.2024).

- 35Measured in per capita GDP, where Norway is top of the Nordic ranking, see, e.g., The economy in the Nordic Region – Nordic cooperation (accessed 29.10.2024).

- 36The study included data recorded between April 2014 and December 2020, and saw a large increase in the cyber-enabled romance fraud after April 2020 (Buil-Gil & Zeng, 2021).