Whistleblowing within the Swedish Police

Stefan Holgersson

Linköping University, Department of Management and Engineering, SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden. Politihøgskolen, The Norwegian Police University College, Oslo, Norway,

stefan.holgersson@liu.sePublisert 28.06.2019, Nordisk politiforskning 2019/1, Årgang 6, side 24-45

Abstract

Research has shown that well-functioning whistleblowing within police agencies is important, because these agencies play a key role in society. The perceived risk of retaliation after expressing criticism is the most important factor that an employee considers when deciding whether to act as a whistleblower. Different individuals and different units hold different views about the risk of retaliation after acting as a whistleblower. The police management in general has a lower perception of the risk of retaliation than other employees have. There is a huge difference between the officially presented picture of a favorable climate in the organization in which employees feel free to express criticism, and the perception of the matter that most employees have. The differences are connected to the presence of impression-management strategies that are intended to maximize the good image of the organization, and are the main reason that whistleblowing is not appreciated, despite assurances from the management that it is important.

Keywords

- Whistleblowing

- Whistleblower

- Police

- Retaliation

- impression-management strategies

Introduction

Whistleblowing is important because it provides the initial stimulus for improving organization efficiency and effectiveness and is often the source of solutions to organizational problems (Miceli, Near & Schwenk, 1991). Even if there is some evidence that a blue code of silence exists in police organizations, most research seems to overstate the code of silence in the police and one reason is that several research studies have been based on investigations about police corruption in the US and Australia (Loyens, 2013). Many scholars suggest that the idea of a universal homogeneous culture in the police is too simplistic and stereotypical (Scripture, 1997; Harrison, 1998; Reiner, 2010; Paoline, 2003; Waddington, 1999; Chan, 1996). Some studies have compared the code of silence followed by police officers with that followed in other occupations (see, for example, Loyens, 2013; Rothwell & Baldwin, 2006). Some of these studies show that police officers are slightly more likely to blow the whistle than civilian public employees (Rothwell & Baldwin, 2006; Wright, 2010).

Research on whistleblowing in police agencies is limited, and several studies have highlighted the need to increase knowledge in this area (Park & Blenkinsopp, 2009; Loyens, 2013; Gottschalk & Holgersson, 2011). This article contributes to knowledge of whistleblowing in police agencies and it sheds light on the issue of whether the culture withint he police is homogeneous. It discusses whether different departments, districts, ranks and regions differ (Loyens, 2013). The starting point of the article is that the culture of the organization is heterogeneous, although it is possible to identify common approaches and phenomena.I t is important to increase knowledge about whistleblowing in police agencies because the police force plays a special role in society. A culture of integrity within the police is important to ensure that policing is democratic and trustworthy (Kutnjak & Shelley, 2008; 2010; Gottschalk & Holgersson, 2011; Tasdoven & Kaya, 2014; Brčvak, 2014).

This article increases our understanding of how managers can act to increase the probability of creating a well-functioning whistleblowing function within an organization. Whistleblowing is often described as a reaction to “misconduct”, but this term does not fully cover all behaviors that may trigger whistleblowing. One example of the latter are structural accountability problems (Blonder, 2010). The definition of whistleblowing used in this study includes not only reactions to behavior that clearly falls within the term “misconduct”, but also such behavior as defective administration, waste or mismanagement of resources, perverting the course of justice, and retaliation against whistleblowers (Smith, 2010). Most definitions of whistleblowing exclude retaliation. Retaliation was included in this study firstly since one of the most important tasks for a police force is to guarantee freedom of speech – a freedom which should include police employees. Secondly, it is against Swedish constitutional law to subject employees in the public sector to negative consequences when they act as whistleblowers (Tryckfrihetsförordningen, Chapter 1, Section 1). If the police force is to retain credibility, it must follow the law. Finally, retaliation against whistleblowers may influence the willingness of others to become whistleblowers (see, for example, Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, 2005).

Most studies into whistleblowing have used questionnaires and interviews, asking people about past actions or about how they would act in hypothetical situations. Descriptions of past actions, however, may not be accurate, and speculation about hypothetical situations is subject to considerable uncertainty (Loyens, 2013; Park & Blenkinsopp, 2008). Leymann (1996) describes how whistleblowing can cause an escalating interpersonal conflict, and points out that a whistleblower risks becoming a target of bullying and stigmatization. Both internal and external actors may misinterpret the situation and consider the employee to be the problem. Research on whistleblowing has often focused either on intended hypothetical reporting, or on the characteristics of employees who have reported wrongdoing. Some studies have described the experiences of whistleblowers. Bjørkelo & Bye (2014), for example, described both intended and actual whistleblowing. One of the most important factors that discourages employees from acting as whistleblowers is a concern about retaliation (Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, 2005; Park & Blenkinsopp, 2008).

A concern that influences a planned behavior is known as a “control factor”. The perceived behavioral control is a psychological construct, rather than a measure of the actual control (Ajzen, 1991). Accordingly, the belief that one risks being punished is central for the probability that a person will act as a whistleblower. Employees are highly influenced by their perception of their leaders’ attitudes, and this determines in many cases how they react towards problems (Wathne, 2012). It is, therefore, of great interest to study how employees within a police organization perceive the risk of retaliation for acting as an internal or external whistleblower.

This article studies the perceived risk of retaliation after acting as a whistleblower as an employee in the Swedish police. It suggests possible causes of the perception of the risk. It is particularly interesting to study the Swedish police in this context, because there is a large difference between the view held by the Swedish Police Union (Polisförbundet) and that expressed by the police management regarding the employees’ perceived fear of retaliation for acting as a whistleblower. The Swedish Police Union believes that acceptance of presenting internal and external criticism is low, while the official picture presented by the police organization is the opposite. It may be fruitful to determine whether the highest police chiefs in Sweden agree with the official image regarding the employees’ perceived fear of retaliation for acting as a whistleblower.

The primary research question for the study is whether there are differences between employees’ fear of retaliation and the management’s opinion of the employees’ fear. If there are differences, two further questions arise. What are the reasons for the differences? What are the possible effects of such this situation?

Theory

Policing in Sweden

The Swedish police has 28,000 employees, of whom about 20,000 are police officers. Three years ago, the Swedish police conducted a major reorganization in which 21 counties formed a national police. The duration of education to become a police officer is 2.5 years.

The Swedish police has been described as a greedy institution (Peterson and Uhnoo, 2012). An organization is seen as greedy when various structural mechanisms clearly exercise power over the individual (Coser, 1967), and organizations in which it is essential to have greater loyalty towards the organization than towards actors outside it (Peterson and Uhnoo, 2012). The concept most often used in Sweden to describe acceptance of internal and external whistleblowing is that the “ceiling is high”. A “high ceiling” in an organization is a metaphor for an open atmosphere, in which all viewpoints are listened to and taken seriously. The fear of retaliation is often mentioned by employees within the Swedish police as a consequence of the “ceiling is low”. Examples of retaliation after acting as a whistleblower in the Swedish police have been described several times in media articles and even books (see, for example, Kjöller, 2015). A research study conducted in a police department in the south of Sweden revealed a widespread opinion among employees in the lowest level of the hierarchy that the “ceiling is low” (Wieslander, 2016).

Literature review

Several areas of research must be considered when answering the research questions posed by this study. One such research areas is, of course, research into whistleblowing. The research literature about whistleblowing is extensive. Whistleblowing can be categorized along three dimensions: formal-informal, anonymous-identified, and internal-external (Park et al., 2008). The various ways of blowing the whistle will be associated with the same attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control (Park & Blenkinsopp, 2009). Management must make two types of decision in response to whistleblowing: (1) disregard the claim or take appropriate action, and (2) reward or retaliate against the whistleblower. The experience of a whistleblower (perceived or actual) will strongly affect the willingness and likelihood of others blowing the whistle in the future (Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, 2005; Casal & Zalkind, 1995).

Employees in an organization have four options when faced with an unsatisfactory situation: (1) leave the organization, (2) blow the whistle, (3) remain loyal to the organization, and (4) ignore the situation (Withey & Cooper, 1989; Bjørkelo, Einarsen & Matthiesen, 2008; see also Hirschman, 1970). Previous research has shown that individuals who possess a higher commitment to the organization are more likely to blow the whistle than leave the organization. Furthermore older, high-performing and more experienced employees are more likely to report wrongdoing in and by organizations (Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, 2005).

Ajzen’s (1991) well-cited theory of planned behaviors (TPB) identifies three components (attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control) that can be used to predict ethical or unethical behavior. The first predictor, the attitude toward the behavior, “refers to the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation or appraisal of the behavior in question” (Ajzen, 1991, p. 188). Subjective norms refers to the “perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behavior” (ibid.). The third predictor, perceived behavioral control, is “the degree of perceived behavioral control, which refers to the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior, and it is assumed to reflect past experience as well as anticipated impediments and obstacles” (ibid.). It is possible to use the theory of planned behavior to predict the probability that a person will become a whistleblower (Park & Blenkinsopp, 2008). TPB was used also in research studies that discussed the differences between intended and actual whistleblowing (Bjørkelo & Bye, 2014).

An extreme view is that whistleblowing can never be justified because an employee must be loyal to the organization. In this view, maintaining secrecy always outweighs other considerations. Another perspective is that whistleblowing involves a compromise between loyalty to the organization and other obligations, and that the line between justified and subversive whistleblowing (Blonder, 2010) is a fine one.

One of the most extensive studies of Australian whistleblowing (WWTW) focused on “public interest” whistleblowing, in which the whistleblower reacts on seeing wrongdoing that clearly affects organizational or social interests that are wider than the personal or private interests of the individual whistleblower. Seven categories of misconduct were identified in the analysis: misconduct for material gain (e.g. bribery or theft), conflict of interest (e.g. failing to declare a financial interest), improper or unprofessional behavior (e.g. sexual harassment), defective administration (e.g. failure to correct serious mistakes), waste or mismanagement of resources, perverting the course of justice or accountability, and reprisals against whistleblowers (Smith, 2010).

Reactions to workplace grievances and bullying are not normally seen as whistleblowing, because such actions mostly affect the interests of individuals, rather than being matters of public interest (Smith, 2010). However, since many researchers have emphasized the importance of a functioning culture of whistleblowing within police organizations (Kutnjak & Shelley, 2007; 2010; Tasdoven & Kaya, 2014; Brčvak, 2014), it is important to consider what happens to persons who act as whistleblowers. Furthermore, it has been argued that there is a gray zone for organizational politics, in which subgroups can leak information and blow the whistle as a part of a political struggle (Loyens and Maesschalck, 2014).

To explain possible differences regarding the expressed perceived fear of retaliation it is possible to use theories such as the theory of selective perception and the theory of selective imperceptions. These clarify how two persons can observe the same thing but interpret it in different ways (see, for example, Dearborn & Simon, 1958; Beyer et. al., 1997).

Other theories have been proposed in the field of organizational research to explain why different points of view of an employee’s fear of retaliation are possible. Many researchers have identified two different layers in organizations and shown that these two layers have very different views when interpreting what and why things happen (Ekman, 1999; Reuss-Ianni, 1993; Manning, 1980; Brunsson, 1989; 1993). Different researchers give different names to the layers, but the observed phenomenon can briefly be described as the view of the top management vs. the view of the employees working in the field. Top management and the administration around them have, for example, a strong trust in documents such as plans, rules and directives. They often believe that what they formulate in such documents affects work practices, even if this is seldom the case (see, for example, Ekman, 1999).

Discrepancies between different hierarchy levels regarding how the fear of acting as a whistleblower is expressed can also be explained by using theories of value branding. It is important for such an organization as the police to be seen as open and transparent. Organizations are often subject to a high level of demand and find it difficult to meet it. This is particularly the case for organizations in the public sector. One important strategy used by modern organizations is to maximize a positive image of the activities (Alvesson, 2013). Legitimacy-building is generally a common behavior in organizations to convince external stakeholders that the operations are working satisfactorily (see e.g. Meyer & Rowan, 1977; DiMaggio, 1983; Alvesson, 2013). Many examples of branding activity carried out by the Swedish police have been identified (Rennstam, 2013). Value branding is receiving increasing attention and resources (Forsell & Ivarsson Westerberg, 2014), and it is, therefore, interesting to consider value branding when analyzing whistleblowing.

Research has also shown that critical information has a tendency to become more positive as it passes along an information chain (Hackman & Oldham, 1980). It has been suggested that organizations should consider the possibility that individuals falsely believe that their primary responsibility is to save face for the organization by covering up wrongdoings (see Goffman, 1959/1990). Furthermore, ICT can cause dysfunctional behaviors in organizations (Lapsley, 2009; Speklé and Verbeeten, 2014) and manipulation/illusionary tricks may result in information that might otherwise be used as a basis for decisions becoming wrong or misleading (Eterno and Silverman, 2012; Alvesson, 2013). Top management should ensure that the internal reporting channels are functioning and are “free from leaks” (Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, 2005).

Research has shown that an unclear whistleblowing procedure in police departments causes confusion. Potential whistleblowers do not know where to turn, which procedure they should follow, and the nature of any protection available (Brčvak, 2014). Encouraging internal whistleblowing has two benefits. Firstly, it will reduce the risk that unacceptable practices remain undetected. Secondly, it will reduce the probability of external whistleblowing, which often damages the reputation of organizations (Park & Blenkinsopp, 2008).

External whistleblowers tend to be more effective in changing organizational practice than internal whistleblowers (Dworkin & Baucus, 1998), although loyalty to the organization as a whole and a desire to avoid public embarrassment may limit the extent of external whistleblowing (Van Maanen, 1978). Employees may decide not to act as an external whistleblower due to a perceived greater risk of retaliation against external whistleblowers than against internal whistleblowers (Dworkin & Baucus, 1998; Park & Blenkinsopp, 2009). External whistleblowers face a different consideration than internal whistleblowers in that they know they are taking a major step that will not be well‑received by the organization. For an external whistleblower, “the decision becomes less ‘should I do this?’ (attitude) or ‘will I be able to do this?’ (perceived behavioral control) but more ‘will I survive doing this?’ Such a decision will be crucially influenced by what they believe significant others will think of their actions.” (Park & Blenkinsopp, 2009, p. 554).

A fear of voicing criticism (Shepherd, Patzelt, Williams & Warnecke, 2014) and information gatekeepers (Bouhnik & Giat, 2015) might lead to some information being misleading. It is important to identify and describe problems in order to improve organizational effectiveness and efficiency (e.g. Miceli, Near & Schwenk, 1991).

The definition of internal whistleblowing used in this article is the action of an employee passing a level of hierarchy and failing to follow the chain of command. This includes initiatives taken by a whistleblower contacting the Bureau of Internal Affairs and making a report. The definition of external whistleblowing used in this article is an official expression of criticism made by an employee, or contact taken by an employee with actors outside the organization to inform them about problems within it.

The literature review suggested that theories from several fields of research may contribute to answering the research questions. However, it was not possible to find research studies that have examined whether there are differences of opinion between the lowest and the highest hierarchy levels in an organization regarding the fear of retaliation for acting as a whistleblower that employees low in the hierarchy perceive. One theoretical contribution of this article is to address this research gap. Another theoretical contribution is the adoption of a holistic approach, using theories from various research areas and using mixed methods to answer the research questions.

Methods

The literature review indicated that it would be fruitful to use mixed methods to answer the research questions. Mixed‑method research combines quantitative and qualitative approaches (Creswell, 2009).

Data collection

One part of the data used in this study is the result of ethnographic research during 18 years in the Swedish police. Ethnographic research is a research method in which researchers can obtain a deep understanding of an organization, of the employees working in an organization, and the broader context in which they work (Myers, 1999). Participant observations and interviews have been carried out during a period of 18 years in the Swedish police at more than 100 police stations, from all former 21 police departments in the Swedish police. (The Swedish police underwent reorganization in 2015, during which all police departments were merged into one authority). More than 2000 employees have been interviewed in different projects, mostly in connection with participant observations, more than 10,000 hours of which were observed in the period 1998 to 2016.

The main focus for the research activities described above was not the employees’ attitudes to the risk of retaliation when acting as whistleblower. However, this aspect was expressed spontaneously by employees in connection with interviews or informal conversations at different hierarchical levels and was also observed. It had been possible to try to answer the research questions by using these longitudinal data. Paoline (2003) states that such data can provide a deeper understanding of an organization’s culture. Studying police officers over time enables changes in the culture of silence to be identified, and Paoline recommends for this reason that observations and interviews are conducted with officers in several research settings. This will enable findings to be triangulated.

It may be difficult to identify some aspects of the culture behind the closed doors of a police station, and it is possible that such aspects are best captured in the field. In contrast, other aspects are difficult to observe in the field, and easier to observe in interviews (Paoline, 2003). However, it was assessed that the quality of the answers of the research questions could be increased by collecting data with a focus on the employees’ perceived risk of retaliation when acting as whistleblower. Therefore, one in-depth study was carried out during 2011 in one police department, included interviews of 123 employees (105 police officers and 18 civil employees) and 100 hours of observation at the main station of the department, and 48 hours in two of the four smaller police stations. In addition, participants were observed during nine shifts of operational work.

All police officers who were asked to participate agreed to be interviewed, while three civilian employees declined. The average age of the 105 interviewed police officers was 37 years and the average length of service was 10 years (median 6 years). Thirty-one of the interviewed police officers were women. The police officers who have been interviewed have not been sorted into different categories. In Sweden, the difference between, for example, a detective and uniformed officer is small. A uniformed officer does many things that a detective does, and it is common to alternate between being a uniformed officer and working with other types of service within the police. Police officers in Sweden have the same education (except some specialists working as child interrogation officers).

The interviews were conducted in Swedish and translated into English. The interviews consisted of a quantitative and a qualitative part. Table 1 and most of the quantitative results presented in this article are from this study.

Another study in 2011 collected quantitative data about whistleblowing from the nine members of the management team in the police district where the in-depth study had been carried out. Twenty-two members of the top management (chief of the police and the highest management positions) of the Swedish police were also interviewed in 2011. Several police officers contacted the author of this article by telephone and others sent documents concerning retaliations against employees.

Some of this material described events that did not fall under the definition of whistleblowing, but it provided interesting data that helped to understand processes in which employees had felt that they had been a subject of retaliation. Moreover, nine cases of extensive retaliation within the Swedish police have been described in a book (Kjöller, 2015), which has also been used to understand the phenomenon. Another source of data was an inquiry in a Swedish police district into the opportunities and obstacles for employees and management to express themselves internally (Wieslander, 2016).

Loyens and Maesschalck (2014) recommend that future research in whistleblowing use qualitative methods, such as participant observations and in-depth interviewing. Such methods bring a holistic perspective and provide insight into the complexity of decision making for street-level bureaucrats. They recommend using a combination of several types of data collection that can complement and validate each other (Lyens & Maesschalk, 2014). This approach was used in the work presented here.

Data analysis

The analysis process initially focused on the quantitative results from the in-depth study in one police district (n=123). The data were structured in different tables for each question asked during the interview. These tables, together with quantitative data from the study of the management team (n=9) and from the study of the top management in the Swedish police (n=22), formed the basis for the next step of the analysis in which qualitative data was used. It was essential to use triangulation (see Denzin & Lincoln, 1998) during the analyses, which sought to consider different data sources and views. Data that could explain a point of view or highlight different perspectives were assessed to be fruitful and to complement other, more often expressed, opinions.

The initial step of the analysis of qualitative data was to sort expressions and observations into different categories that could explain the causes of the perceived risk of retaliation and that could explain any differences in the expressed perceptions that became apparent. The analysis took its starting point in the categories that had been identified, and we then sought theories that could enrich the understanding of these findings. Loyens and Maesschalck (2014) pointed out that most whistleblowing studies have attempted to find a single model to explain the data, and they suggest that whistleblowing studies that capture the empirical complexity of social life by using different pathways should be carried out. This study has adopted such an approach. Theories were used in combination with further categorization of the empirical findings in a reflexive research approach (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2010; Bryman & Bell, 2007).

This process led to a deeper insight into the phenomena that had been observed, in which it was possible to use findings from other research areas when drawing conclusions from the empirical material. The review of current theory used general research about whistleblowing (e.g. Park et al., 2008), and research that showed that open discussions are not encouraged within the Swedish police (e.g. Wieslander, 2016). However, the research process led to the insight that theories from other research areas, such as branding (e.g. Alvesson, 2013), were valuable in explaining the empirical findings. The theory section can, therefore, be seen to some extent as part of the results section. The analysis showed that it was valuable to use other theories than the commonly used theory of whistleblowing to explain the observed phenomena. The theory section has, therefore, been structured in a way that makes it easy for the reader to follow the main lines of argument and their relationships to the research results.

Results

Perceived risk of retaliation when acting as whistleblower

The Swedish concept of high and low “ceilings” must first be examined. Employees and the Swedish Police Union on one side have strongly proclaimed that “the ceiling is low”, while the police management has expressed the opposite opinion, that “the ceiling is high”. The reason for the difference in opinion might be that the two camps are using different definitions of “high ceilings”. An in-depth study conducted in one district (n=123) gave researchers an opportunity to examine whether this is the case.

Three definitions of a “high ceiling” became apparent during the analysis. Most (76%) employees considered that to work in an organization with “high ceilings” meant that the employees “are able to criticize without a risk for retaliation”. Somewhat fewer (17%) of the employees considered that an organization with “high ceilings” is an organization in which “there is a good dialogue, where the management listens to arguments”. A small number (7%) of employees considered that the existence of “high ceilings” is shown by the “management should do as the employees suggest”.

It is not surprising that employees who define high ceilings as management following employee suggestions believe that the police organization has low ceilings. However, most of the employees who gave one of the other two definitions felt that the risk of retaliation was so great that it significantly affected their willingness to act as an internal whistleblower (88%) or as an external whistleblower (95%). A perceived risk of retaliation when acting as a whistleblower has become apparent in other studies conducted by the author in the 21 former police districts in Sweden, even in studies in which the focus was not on whistleblowing.

The fear of acting as whistleblower was high in all districts except one, where the climate of communication between employees and management was significantly better than in the other districts. The management of this department had decided that someone from the top hierarchy should participate in the operational work every weekend. High-ranking managers were therefore not seen as occasional guests, which was the case in other departments when high-ranking officers visit the operational work. The impression was that this made it easier to become an internal whistleblower. The perceived risk of retaliation when acting as an external whistleblower was, however, high also in this department.

Interviews and observations from different parts of Sweden showed that there is generally a great concern relating to acting as a whistleblower. It is possible, however, to question how representative the results from the in-depth study are of results from other districts in Sweden. Wieslander (2016) conducted 33 in-depth interviews and participant observations with informal interviews with over 100 employees in another district, and arrived at similar conclusions about the great fear of retaliation when acting as a whistleblower. Enquiries by the police union have also shown that there is a prevailing fear associated with presenting criticism (Polisförbundet, 2012).

Previous work has shown that there are differences between both employees and units in the perceived risk of retaliation when acting as a whistleblower. The in-depth studies confirmed these findings. Table 1 shows that no one in Unit A believed that it was safe to act as an internal whistleblower, while four employees in Unit C had such an opinion.

Table 1:

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Unit A | 12 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2.86 |

Unit B | 6 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3.55 |

Unit C | 4 | 7 | 17 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3.86 |

All | 22 | 22 | 28 | 18 | 14 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 3.45 |

Civilian employees perceived the risk to be lower (mean 4.88) than police officers (mean 3.18). However, three civilian employees declined while no police officers did. The reactions on being asked to take a part gave the impression that these three employees perceived the risk of retaliation to be high, which may mean that the difference in perceived risk is lower than the results presented here. Persons in management positions generally believe that it is possible to act as whistleblower without becoming subject to retaliation.

Anonymous data were collected from the management team in the district in which the in-depth study had been carried out, and showed that these employees were considerably more positive to the possibility of acting as a whistleblower without the risk of retaliation that the rest of the employees (mean 6.33 for management, to be compared with 3.45 for all employees). Employees in the management team gave values between three and eight for the perceived risk of retaliation. At the presentation of the results to the management team, the highest chief expressed spontaneously with great surprise, but without an accusing tone of voice: “What! Who responded three?”. No-one answered the question. Other evidence (interviews) suggests that the two respondents in the management team who had given the grade of five also did not dare to criticise. Some members of the management team seemed to be extremely surprised by the result.

Members of the management team were asked how they thought that the employees perceived the risk of retaliation when acting as internal whistleblower. Their answers were close to those given by the employees (mean 3.88 for the management team, to be compared with 3.45 for other employees). In connection with an information meeting about the research study, 30 employees were selected randomly and were questioned how they estimated that the mangagement team perceived the employees’ fear of retaliation. The employees’ answer (mean 5.45) showed that it was obvious that the employees did not believe that the management team understood how extensive the fear of retaliation was. Managers have proclaimed both internally and externally that there are high ceilings within the Swedish police, which may explain why employees believe that the management underestimate the problem. This is an example of the negative effects of an intense focus on value branding within the Swedish police. The aim of looking good might limit the possibilites of being good (Holgersson & Wieslander, 2017)

Even through the members of the management team assess the risk of retaliation to be almost the same as the assessment of the employees, management undervalued the employees’ perception of the risk of retaliation. Seven of nine members in the management team believed that less than 50% of employees had heard of others who had been a subject of retaliation after expressing criticism. Only one person in the management team had given the same range (80–90 percent) as that given by the employees. Members of the top management in the Swedish police (n=22) perceived the risk of retaliation when acting as whistleblower as much lower than the management team in the in-depth study perceived it. About a quarter of the top management believed that fewer than 10% of the employees perceive that “there is a risk (which is not negligible) to be a subject of retaliation due to internal criticism/comments to someone else than the nearest chief/supervisor”. Barely half of the top managers believed that the value is less than 20%, and only one of the top managers believed that it is greater than 50%. The correct figure is 88%. Members of the top management in the Swedish police estimated the risk of retaliation when acting as whistleblower higher than they believed that the employees perceived the risk. Approximately half of these top managers (10 of 22) believe that there is a non-negligible risk. About a third of the top management (7 of 22) had refrained from presenting criticism in the police due to the risk of negative consequences for themselves.

Interviews and observations indicate that some criticism is more taboo than other criticism. In particular, it is perceived to be risky to criticize organizational units, projects or activities that senior managers have highlighted as successful, or that in other ways are prestigious:

The police authority presents a misleading picture, but it would be a career suicide to criticize any of the projects that chiefs of the county police have promoted externally. (Interview, 11 May 2011)

Criticizing phenomena or conditions for which the police organization is not solely responsible, such as inadequate resources or criticism of the general police salary levels, is perceived to be less risky. The perceived risk of retaliation following external criticism was higher than the perceived risk of retaliation following internal whistleblowing (2.36, to be compared with 3.45). These conclusions are compatible with previous research (Park & Blenkinsopp, 2009; Dworkin & Baucus, 1998). The interviews revealed clearly that most employees would never even think of expressing external criticism. The chairman of the Swedish Police Union has stated that journalists often complain that police employees do not dare to speak.

Experience and awareness of retaliation

Many employees mentioned spontaneously in interviews cases in which they believe that criticism had led to negative consequences for the one who acted as whistleblower. This was also the case in the in-depth study, in which 85% had heard of someone who had been a subject of retaliation. About a quarter had experienced retaliation after expressing criticism themselves, and two-thirds had seen it happen to someone close. Many believed that the negative effects were a result of having expressed criticism, but it was, clearly, impossible to prove this. It was more of a subtle feeling. This circumstance may explain why employees far down in the organization and the management have different views about the risk of acting as a whistleblower.

The Swedish police organization has two distinct hierarchical layers (Ekman, 1999). The way information is changed when members in different layers communicate with each other may explain the differences in the beliefs of the employees’ perceived risk of retaliation when acting as whistleblower between the management team in the in‑depth study and the members of the top management in the Swedish police.I n both layers, it is common that employees state that they dare to express criticism, but between the two layers it appears that there is a great need to customize the information. This adjustment may take the form of obvious misinformation, or it may take the form of small changes to the information as it passes along a chain of hierarchy, such that the final version gives a more positive impression (see, for example, Hackman and Oldham, 1980). The lowest hierarchy level may say, for example, that something “…works very poorly”.The next level skips the word “very”, and when the information has passed through more hierarchal levels, it may have become: “It is possible to make some improvements”. The next hierarchy level may summarize the information by saying that the phenomenon works “…quite well”. Finally, when the information reaches the highest hierarchical level, the word ‘quite’ may have been removed, and the information now no longer indicates that an urgent problem needs attention. This is illustrated by the following excerpt from an interview:

I [...] can [...] say that often the only purpose of follow-ups and presentations is to make politicians happy. We [...] fabricate words that we know are not a true description of reality, but we know that the description we give satisfies our senior managers. They must, in turn, satisfy their superiors. (Reference to a publication done by the author of the paper)

About half of the top management (12 of 22) interviewed stated that information is changed and adjusted to a high degree in the police as it passes hierarchy levels. It is important within the Swedish police to follow the chain of command. Some managers may have a different opinion, but they generally conclude that it is better to follow the chain of command than omit a level and report a problem. This leads the managers to fail to act, and the problem thus persists. The result is that important information never reaches higher decision makers. Information and communications technology (ICT) often plays an important role for the top management, but its use contributes to a misleading picture of conditions (Eterno & Silverman, 2012). Further, it is easy to point to ICT when attempting to give a good impression (Speklé & Verbeeten, 2014). Someone who questions information presented from ICT and challenges the value branding is generally highly unpopular.

The management sometimes suggests that proof of a “high ceiling” in the Swedish police force comes from the fact that several police officers have dared to criticize the police externally. However, it is common that these police officers had left the force or were in the process of doing so. Further, the criticism challenged the value branding to a low degree. Recent criticism has concerned mainly low salary and a lack of resources, and has not, for example, suggested that the police force is using its resources poorly. Some employees have acted as whistleblower because they believed that there was no risk, and some employees have acted as whistleblower even though they believed that they may be a subject of retaliation. Most of the latter stated that they had miscalculated the effect, and that the retaliation became more prolonged and more extensive than they had expected. In some cases, the retaliation led to the employee leaving the police (see also Wieslander, 2016).

A few employees who acted as a whistleblower retained their opinion that it is safe to act as a whistleblower, even if they challenge the value branding that is common in organizations such as the Swedish police (Alvesson, 2013). Those who claim that there are “high ceilings” in the Swedish police force state that there are no clear cases (or very few clear cases) of someone being punished for acting as a whistleblower. This is made clear by two interviews with senior managers:

I suggest that the employees create myths about punishment for expressing a point of view. This may occur in smaller groups. But it is important to remember that a person may fail to be promoted for other reasons than having blown the whistle. (Reference to a publication done by the author of the paper)

It's not that we do not accept criticism from employees with another point of view. That may be so, but it is also the way in which the criticism is put forward. What substance there is in it. There are those who put forward ideas that are feasible to implement. That are great ideas. Then there are those who sit on the sidelines and just moan. (Reference to a publication done by the author of the paper)

The employees, however, can interpret treatment as being a consequence of a person speaking out, and highlighting problems that others do not dare to. Furthermore, a lack of exercises in active listening skills will probably have negative effects on the way in which the management response to the employees’ criticism is perceived.

Another reason that caused employees to be afraid of acting as whistleblower is in-group recruitment. Employees believed that those who have a similar vision or perception as the recruiting manager will be employed. The interviews showed that managers often have genuine belief that the recruited person is suitable for a specific position, and they want to choose someone with whom they believe that they can have a friction-free relationship. Their intention was not to punish someone who had drawn attention to a problem, but the recruitment process favors employees who either have similar beliefs and attitudes as the manager, or are able to disguise the fact that they hold opposite beliefs and attitudes.

Employees are convinced that you need to be friends with the right people. Further, employees have concluded that it is important not to offend managers, to please them, and to say what they want to hear. Highly ranked managers who talk to employees far down in the organization (with the expressed intention of obtaining an accurate picture of operations directly from the source) thus face the risk of receiving an adjusted picture. Furthermore, it has emerged that individuals who put forward opinions unambiguously and clearly risk being seen as inflexible and difficult even though they may have taken on the role of expressing what others are saying around the coffee table, but do not dare to put forward. There is a risk that employees are cautious at employee meetings and evaluation meetings, and do not question the ideas that the highly ranked managers proclaim. The risk of wrong decisions being taken is high in these conditions (see Janis, 1972; Hart, 1991).

Participant observation and interviews have shown that these problems are widespread in the Swedish police. When wrong decisions have a negative effect on performance, the need for whistleblowing increases. However, acting as a whistleblower in such circumstances may be more difficult, because decision makers want to save face (often called “responsibility effects”, see, for example, Drummond, 2014), and because criticism challenges the value branding to a higher degree.

An in-depth study in one district showed that employees in general did not believe that presenting criticism of one’s immediate supervisor was a problem (mean 6.58). This agrees with results from a similar question conducted by the National Police Board. The latter survey is sometimes presented by the highest police management as evidence that there are “high ceilings” in the police. Interviews and observations, however, have shown that employees who stated that there are no problems with criticizing one’s immediate superior even so adapt information or avoid presenting criticism in actual cases. Even if the management proclaims that acting as whistleblower is without risk, it is very rare that the management officially criticizes the organization. Previous research has shown that intended and actual whistleblowing may differ (Björk & Bye, 2014).

Recruitment seems to be a factor that sends clear signals about which approach pays off. The following extracts from interviews with two employees working in the field demonstrate this point:

He has no backbone, that guy. He will be able to go as far as anyone. (Reference to a publication done by the author of the paper)

Operational issues and skills seem to be very irrelevant in the selection of managers and those questions usually end up in the background [...] Instead, they want managers who fit into the pattern of the hierarchy. (Reference to a publication done by the author of the paper)

Interviews showed that it is vital to act and say things that can contribute to the value branding. It is often difficult for actors outside the police to reveal that the images presented are false. Without whistleblowers, the risk that images and explanations are questioned is, therefore, limited, and this is the main reason that external whistleblowers are seen to be huge threats to the Swedish police, and handled accordingly.

The results presented here show that the perceived risk of retaliation, and not the actual risk, is the most important factor when deciding whether to act as a whistleblower. This conclusion is supported by other research (Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, 2005; Park & Blenkinsopp, 2008). Those who themselves believe that they have been exposed to retaliation were those in the in-depth study who assessed the risk as highest (mean 3.54). It is interesting to note that the risk of acting as a whistleblower was estimated to be nearly the same by those who have seen retaliation against employees around them (mean 3.82) as by those who have only heard of a case of retaliation (mean 3.95).

Researchers have shown that the actual or perceived experiences of whistleblowers strongly affect the willingness of others to act as whistleblowers (Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, 2005; Casal & Zalkind, 1995).

A quiet and scared organization may thus be the result of a single example of retaliation. Such an act can prevent many others from becoming whistleblowers. The in-depth study shows that this type of story creates and maintains fear. This conclusion was also found in another study in another police district: “Despite the concrete facts behind all examples, it is the impression, and worries for retaliation, that many employees take into consideration” (Wieslander, 2016, p. 5).

The employees who had not heard of persons being subject to retaliation (15%) believed to a lesser degree (mean 5.72) that it would be a consequence of criticism. However, this did not mean that they considered it to be safe (which would correspond to a value of 8), and qualitative interviews show that a value below 6 entails a very low willingness to act as a whistleblower. The results presented here show that the perceived risk of retaliation is strongly embedded in the organizational culture. This conclusion is consistent with the findings of the study conducted by another researcher in another police district: “Employees are socialized into an atmosphere of keeping criticism and viewpoints to themselves or within the nearest internal group” (Wieslander, 2016, p. 7).

A vicious circle

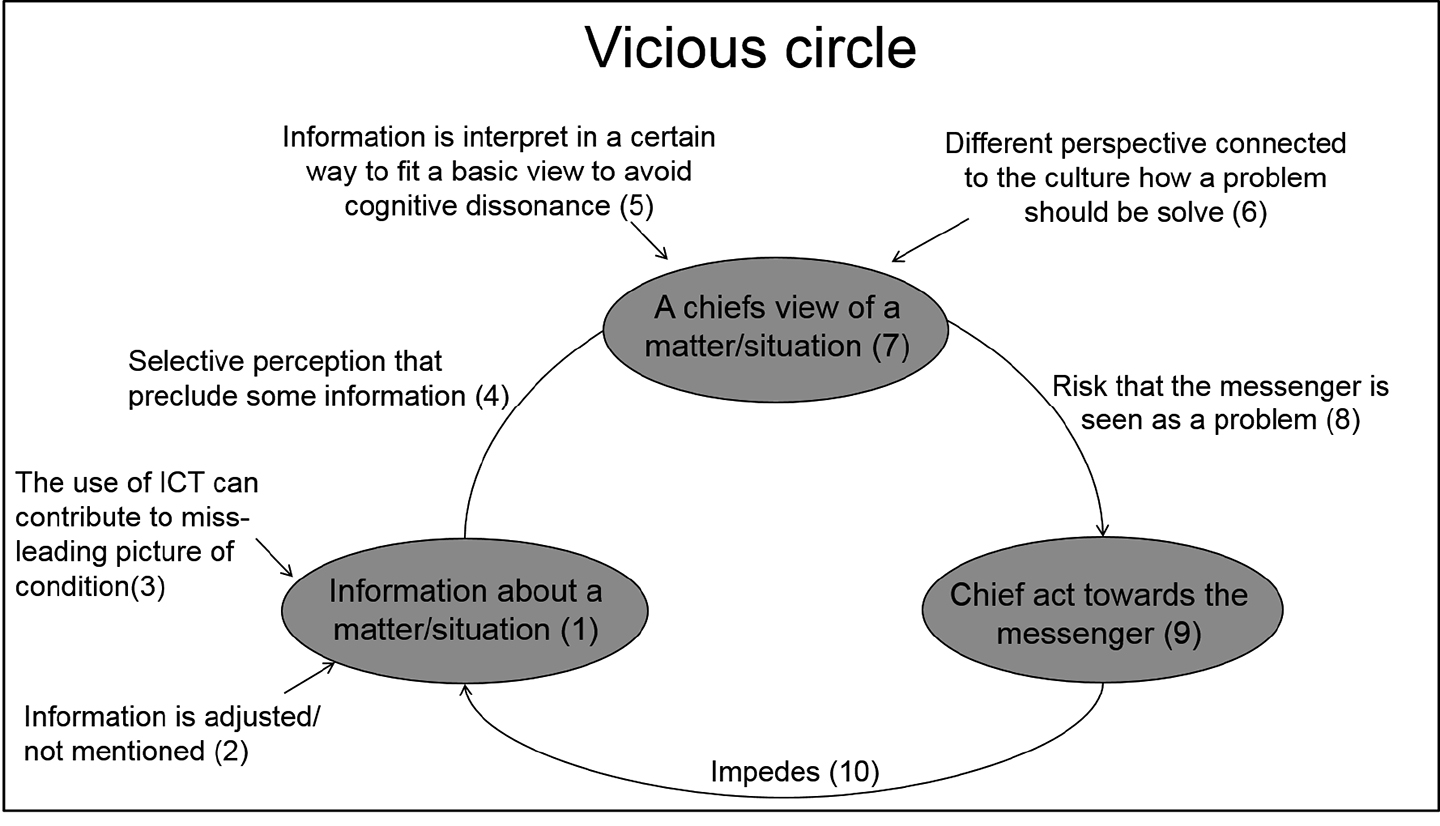

The results presented above in the light of different theories allow us to create a model in which the organizational culture of the Swedish police forms a vicious circle (Figure 1).

Figure 1

A vicious circle

The vicious circle takes the following form: (1) information about a matter/situation/condition is adjusted (2) as it passes upwards in the hierarchy (see, for example, Hackman & Oldham, 1980), while the use of ICT can easily result in a misleading picture (3) of the condition (see Eterno & Silverman, 2012). Even if information that indicates clearly that a specific condition exists, the selective perception and selective imperception of managers (see, for example, Dearborn & Simon, 1958; Beyer et. al., 1997) can result in a failure to perceive certain information (4).

Even when a problem or a factor is mentioned by the management in a basis for a decision, there is a risk that its importance is underestimated when it does not fit with the basic view of the management (5). This is necessary to avoid cognitive dissonance (see, for example, Festinger, 1957).

Different perspectives (6) may lead not only to different perceptions of a problem, but also to different opinions of how a problem should be solved. Research has suggested that persons at a high hierarchy level interpret what happens and why it happens in a different way than employees at a low hierarchy level (Ekman, 1999; Reuss-Ianni, 1993; Manning, 1980). All the steps described above form the basis of a manager’s view of the matter/situation (7), and the manager must choose which opinion is the most accurate.

There is a risk that someone who criticizes and causes turbulence is seen as a problem (8), and the problem that the person is trying to highlight is ignored (see Leymann, 1996). This phenomenon obeys what is known as “attribution theory” (Jones, 1984). The manager then acts against the person who is seen as the problem (9), and this raises the risk that the treatment of other conditions will be impeded, because employees will not dare to criticize due to the fear of retaliation. The leads to the image that the managers receive about a condition differing to an ever-increasing degree from the picture at the bottom of the hierarchy, and the information that reaches the management through other channels becoming increasingly alien for the management. Persons who act as whistleblowers and who describe a problem, therefore, become known as troublemakers with odd views, rather than employees who describe an important matter in a true and fair way.

The process described above influences how a highly ranked manager interprets a matter and the following actions. A vicious circle arises. It is possible to draw parallels with research about the effect of “the spiral of conflict” (Andersson & Pearson, 1999; Bjørkelo, Ryberg, Matthiesen & Einarsen, 2008).

It is possible to identify several examples of the vicious circle that I have described in the Swedish police. One example is the spectacular failure of the huge IT project PUST. Strong indicators that the development of the system should be terminated were dismissed, and persons who drew attention to problems were treated as the main problem. Another example is the work against organized crime in socio-economically disadvantaged areas. Some police officers stated their belief of what would happen if the police did not give priority to working in this type of area. These police officers were treated as a problem, and the police presence in this type of area was cut down instead of being increased. Some years later, experience had shown that the early warnings were justified. A similar example is how the management acted when faced with problems that had been identified in the police work against narcotics and traffic crimes (see also, for example, Kjöller, 2015, where it possible to identify the behavior exemplified by the vicious circle in Figure 1).

Discussion

When the atmosphere in an organization is such that comments, criticism and suggestions are not handled in a positive manner, the conditions for internal whistleblowing are not good. This leads to frustration, and a failure of the organization to develop. The Swedish police is far from being a learning organization (Antén Andersson, 2013). Several studies have shown that internal whistleblowing is important for the development of an organization (Miceli, Near & Schwenk, 1991).

The failure of an organization to develop as it should generates additional frustration for employees who care about how the operation functions. These are the employees most likely to blow the whistle (Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, 2005). When internal whistleblowing is not functioning, external whistleblowing becomes more necessary (Park & Blenkinsopp, 2009). This brings criticism from the internal realm to the external, which may have negative effects for the organization. Further, if an organization does not take advantage of internal criticism, there is a risk that the problems grow and become the target of extensive external criticism. This has happened in the Swedish police on several occasions. One unit, for example, was held up as an example of a well-functioning unit by the police authority, while internal and external warning signals were ignored. Eventually, the chief parliamentary ombudsman investigated the work of this unit:

The results of the investigation are the most disappointing in terms of shortcomings of the police investigating crime that I have come into contact with during my six years as chief parliamentary ombudsman. (JO, 2009, p. 1)

The concept of “high ceilings” must be discussed. In an organization with high ceilings, is the real risk or the perceived risk of being a subject of retaliation low? It is important that senior managers realize that the perception of risk is crucial when employees consider whether to act as a whistleblower. The work presented here shows that the recruitment processes are important when employees form an impression of what happens to whistleblowers (see also Kjöller, 2015). One possible approach is to intentionally recruit some employees who are seen as outspoken. This would send a clear signal and bring a diversity of opinion and actions to the management team. It is possible to draw parallels between whistleblowers in the Swedish police and police from ethnic minorities. Peterson and Uhnoo (2012) have shown that the latter are seen as “outsiders” within the Swedish police, which they characterize as “greedy”.

As described earlier, many organizations can be seen as consisting of two distinct layers. This has several consequences. When employees present criticism, there is a risk that the perception that the top management has of the matter does not match the perception of the employees. The top management replies to the criticism, and the employees, in turn, perceive the views of the top management as completely alien. They conclude that the management is not listening and is not receptive to their comments. Information is adjusted as it travels both upwards and downwards in the organization, and the images seen in the two layers become completely different. Three factors amplify the problem: a lack of active listening skills, a principle that it is important to follow the chain of command, and fear of retaliation after acting as whistleblower. The work presented here has shown that there might be a risk that the criticism is dismissed as irrelevant, and that a person who presents criticism will be seen as the problem (see, for example, Kjöller, 2015). We have described how this contributes to creating a vicious circle, which then can be difficult to break.

The Swedish police management has emphasized that the police force is characterized by great openness and transparency, which they describe using the Swedish metaphor of “high ceilings”. Some executives have a genuine belief that this is the case, but the previous work (references) has shown that the claim that the police force has “high ceilings” is stimulated also by an aim to present an image of the police as a modern organization. This creates a mistrust towards the management, and a suspicion that they do not understand the culture.

The importance of value branding creates difficulties for those considering acting as a whistleblower. Value branding naturally leads to the conclusion that external whistleblowers are problematic, because they challenge the positive image that the police management wants to create. Internal whistleblowing is also affected by a focus on value branding, since the latter ensures that how things look is more important than how things work. Other researchers have shown that legitimacy-building activities are given priority in many organizations, and in the Swedish police (Alvesson, 2013). This type of activity has become increasingly important (Forsell & Ivarsson Westerberg, 2014), and as long as it remains extensive, the risk that whistleblowers are resisted remains high.

Conclusions

There is a widespread belief among police employees that there is a serious risk of retaliation against whistleblowers. In one police district, 88% of the employees believed that the risk of retaliation was so large that it seriously affected their willingness to act as an internal whistleblower. The perceived risk of retaliation after acting as an external whistleblower was higher (95%). Many top managers share this view. Nearly half of the top management in the Swedish police believe that there is a risk associated with acting as an internal whistleblower, despite the official statement from the police that the organization has “high ceilings”. The Swedish metaphor of a high ceiling describes an open and accepting atmosphere, in which employees dare to express their views and present criticism both internally and externally.

The perception of risk differs between units, hierarchal levels and individual employees. In general, the management perceives the risk of retaliation after acting as a whistleblower lower than employees working on the front lines of the organization perceive it. However, it is very rare that the management officially criticizes the police.

The prevalence of intended and actual whistleblowing differs. Most employees stated that there is no risk associated with presenting criticism to the nearest supervisor and that they would do so if there was a problem (intended whistleblowing), but the results show that most avoid presenting criticism and adapting information (actual whistleblowing). This has the effect that information is changed as it passes along the hierarchal chain (see Hackman and Oldham, 1980), and the information that reaches the top management differs greatly from the initial information. Two layers have been identified, and the risk of information change is especially high when employees from the lower layer must give information to the upper layer.

ICT plays an important role and may contribute to creating a misleading picture of conditions. It contributes also to the idea that it is important to follow the chain of command. This, in combination with a high perceived risk of acting as a whistleblower, exacerbates the situation. There is a risk that employees who highlight problems are seen as troublemakers and moaners. A vicious circle can easily arise, in which employees become more afraid of acting as whistleblowers, which makes it more difficult for the top management to manage matters and situations in an adequate manner.

Some criticism is more taboo than other criticism. Many organizations desire to create an impression of a well-functioning organization (see, for example, Alvesson, 2013), and this has been identified as a major problem that inhibits whistleblowing. Information from whistleblowers challenges the value branding that communication units and the management are trying to create. The talk of “high ceilings” and the importance of well-functioning whistleblowing will remain simply talk as long as value branding is given such a high priority in the Swedish police.

This study has used findings from several research fields to explain phenomena that had been revealed in the empirical material. It might be fruitful in a future study to take a narrower focus, and use one theory when analyzing and presenting the results. Furthermore, the number of employees interviewed in the in-depth study was low. Further studies in other areas, especially for civil employees, will also be useful. Civil employees within the police perceived the risk of retaliation when acting as whistleblower to be lower than police officers did, but only a few civilians were interviewed. In addition, three civilians declined to participate in the study, and this may have been because they were afraid to talk about the subject. More quantitative data should be obtained from employees in management positions concerning how they perceive the risk of acting as a whistleblower. Likewise, other cases should be studied with the same approach, in order to minimize researcher bias.

References

-

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

-

Alvesson, M. (2013). The triumph of emptiness, consumption, higher education, and work organization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

Alvesson, M.a nd Sköldberg, K.( 2010). Reflexive methodology : New vistas for qualitative research, 2 nd ed. , Sage Publications Ltd ., London.

-

Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471.

-

Antén Andersson, A.-C. (2013). Är polisen en lärande organisation? [Is the police a learning organisation?] Rikspolisstyrelsens utvärderingsfunktion. Rapport 2013:6. Stockholm: Rikspolisstyrelsen

-

Beyer, J.M., Chattopadhyay, P., George, E., Glick, W.H., Ogilvie, D.T., Pugliese, D. (1997). The selective perception of managers revisited. Academy of Management Journal, 40 (3), 716–737.

-

Bjørkelo, B., Einarsen, S. and Berge Matthiesen, S. B. (2010). Predicting proactive behaviour at work: Exploring the role of personality as an antecedent of whistleblowing behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 83 (2): 371–394.

-

Bjørkelo, B., & Bye, H. H. (2014). Intended and actual whistleblowing: Past, current and future issues. In A. J. Brown, R. E. Moberly, D. Lewis, & W. Vandekerckhove (Eds.), International handbook on whistleblowing research (pp. 133–153). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

-

Bjørkelo, B., Ryberg, W., Matthiesen, S. B., & Einarsen, S. (2008). When you talk and talk and nobody listens: A mixed method case study of whistleblowing and its consequences. International Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 13(2), 18–40.

-

Blonder, I. (2010). Public interests and private passions: A peculiar case of police whistleblowing. Criminal Justice Ethics, 29(3), 258–277.

-

Brčvak, D. (2014). Whistle-blowing in the Montenegrin Police. Germany: Stability Pact for South Eastern Europe.

-

Brunsson, N. (1989). The organization of hypocrisy: Talk, decision and action in organizations. Chichester, UK: John Wiley.

-

Brunsson, N. (1993). Ideas and actions. Justification and hypocrisy as an alternative to control. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 18(6), 489–506.

-

Bryman, A., and Bell, E. (2015), Business research methods. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

-

Casal, J. C., & Zalkind, S. S. (1995). Consequences of whistle-blowing: A study of the experiences of management accountants. Psychological Reports, 77(3), 795–802.

-

Chan, J. (1996). Changing police culture. British Journal of Criminology, 36(1), 109–134.

-

Coser, L. (1967). Greedy organisations. European Journal of Sociology, 8(2), 196–215. doi:10.1017/S000397560000151X

-

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications.

-

Dearborn, D.C. & Simon, H.A. (1958). Selective perception: A note on the departmental identifications of executives. Sociometry, 21, 140–144.

-

Denzin, Norman, K. & Lincoln, Yvonna, S. (1998). Entering the field of qualitative research. Strategies of qualitative inquiry; Sage Publications, CA: Sage.

-

DiMaggio, P. I. (1983). State expansion and organizational fields. In R. H. Hall & R. E. Ouinn (Eds.). Organizational theory and public policy. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

-

Drummond, H. (2014), Escalation of commitment: When to stay the course? The Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 28 No. 4, pp. 430-446.

-

Dworkin, T. M., & Baucus, M. S. (1998). Internal vs. external whistleblowers: A comparison of whistleblowing processes. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(12), 1281–1298.

-

Ekman, G (1999). Från text till batong .– Om poliser, busar och svennar, Ekonomiska forskningsinstitutet vid Handelshögskolan. Stockholm: Handelshögskolan.

-

Eterno, A., & Silverman, E. (2012). The crime numbers game: Management by manipulation, New York: CRC Press.

-

Festinger, L. (1957), A theory of cognitive dissonance, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA.

-

Forsell, A., & Ivarsson Westerberg, A. (2014): Administrationssamhället. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

-

Goffman, E. (1959/1990). The presentation of self in everyday life. London: Penguin Books

-

Gottschalk, P., & Holgersson, S. (2011). Whistle-blowing in the police. Police Practice and Research, 12(5), 397–409.

-

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley

-

Harrison, S.J. (1998). Police organizational culture: Using ingrained values to build positive organizational improvement. Journal of Public Administration and Management: An Interactive Journal, 3 (2).

-

Hart. P. (1991). Irving L. Janis’ victims of groupthink. Political Psychology, 247–278.

-

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states (Vol. 25). Harvard University Press.

-

Holgersson, S., & Wieslander, M. (2017). How aims of looking good may limit the possibilities of being good: The case of the Swedish Police. Presented at The 33rd EGOS Colloquium “The Good Organization”, 6–8 July 2017, Copenhagen.

-

Ivkovlc, S. K., & Shelley, T. O. C. (2007). Police integrity and the Czech police officers. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice,31(1), 21–49.

-

Janis, I. (1972). Victims of groupthink: A psychological study of foreign policy decisions and fiascoes. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin.

-

JO (2009). Kritik mot polisen för långsam handläggning av bedrägeriärenden –en granskning av handläggningstiderna vid en bedrägerirotel i Stockholm.2 576–2009. Stockholm: Justitieombudsmannen.

-

Jones, E. E. (1984). Social stigma. The psychology of marked relationships. New York: Freeman.

-

Kjöller, H. (2015). En svensk tiger:v ittnesmål från poliser som vågat ryta ifrån [A Swede will be quiet, testimony from police officers who dared to speak]. Stockholm: Fri tanke förlag.

-

Kutnjak Ivković, S., & O'Connor Shelley, T. (2008). The police code of silence and different paths towards democratic policing. Policing & Society, 18(4), 445–473.

-

Kutnjak Ivkovic, S., & O'Connor Shelley, T. (2010). The code of silence and disciplinary fairness: A comparison of Czech police supervisor and line officer views. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management,33(3), 548–574.

-

Lapsley, I. (2009). New public management: The cruellest invention of the human spirit? Abacus: Accounting, Finance and Business Studies, 45(1), 1–21.

-

Leymann, H. (1996). The content and development of mobbing at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 165–184.

-

Loyens, K. (2013). Why police officers and labour inspectors (do not) blow the whistle: A grid group cultural theory perspective. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 36(1), 27–50.

-

Loyens, K. and Maesschalck, J. (2014). Whistleblowing and power: New avenues for research, in Lewis, D., Moberly, R., Vandekerckhove, W. (2014), International handbook on whistleblowing research. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

-

Manning, P. K. (1980). Organization and environment: Influences on police work. In R. V. G. Clarke and J. M. Hough (Eds.), The effectiveness of policing. Aldershot, UK: Gower.

-

Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., & Viswesvaran, C. (2005). Whistleblowing in organizations: An examination of correlates of whistleblowing intentions, actions, and retaliation. Journal of Business Ethics, 62(3), 277–297.

-

Meyer, J., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations. Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363.

-

Miceli, M. P., Near, J. P., & Schwenk, C. R. (1991). Who blows the whistle and why? Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 45(1), 113–130.

-

Myers, M. (1999). Investigating information systems with ethnographic research.C ommunications of the AIS, 2(4), Article 1.

-

Paoline, E. A. III (2003). Taking stock: Toward a richer understanding of police culture. Journal of Criminal Justice, 31(3), 199–214.

-

Park, H., & Blenkinsopp, J. (2009). Whistleblowing as planned behavior–A survey of South Korean police officers. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(4), 545–556.

-

Park, H., Blenkinsopp, J., Oktem, M. K., & Omurgonulsen, U. (2008). Cultural orientation and attitudes toward different forms of whistleblowing: A comparison of South Korea, Turkey, and the UK. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(4), 929–939.

-

Peterson, A., & Uhnoo, S. (2012). Trials of loyalty: Ethnic minority police officers as ‘outsiders’ within a greedy institution. European Journal of Criminology, 9(4), 354–369.

-

Polisförbundet (2012). Medlemsundersökning maj 2012. [Members survey, May 2012]. Stockholm: Polisförbundet.

-

Reiner, R. (2010). The politics of the police. Oxford University Press.

-

Rennstam, J. (2013). Branding in the sacrificial mode – A study of the consumptive side of brand value production. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 29(2), 123–134.

-

Reuss-Ianni, E. (1993). Two cultures of policing. Street cops and managements cops. London: Transactions Publishers.

-

Rothwell, G. R., & Baldwin, J. N. (2006). Ethical climates and contextual predictors of whistle-blowing. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 26(3), 216–244.

-

Scripture, A. E. (1997), The sources of police culture: Demographic or environmental variables?, Policing and Society, 7(3), 163–176.

-

Smith, R. (2010). The role of whistle-blowing in governing well: Evidence from the Australian public sector. The American Review of Public Administration, 40(6), 704–721.

-

Speklé, R. F., & Verbeeten, F. H. M. (2014). The use of performance measurement systems in the public sector: Effects on performance. Management Accounting Research, 25(2), 131–146.

-

Tasdoven, H. & Kaya, M. (2014) The impact of ethical leadership on police officers’ code of silence and integrity: Results from the Turkish National Police, International Journal of Public Administration, 37:9, 529–541

-

Van Maanen, J. (1978). On watching the watchers. In P.K. Manning and J. Van Maanen (Eds.). Policing: A View from the Streets. New York: Random House, p. 309–350.

-

Waddington, P. A. J. (1999), Police (canteen) sub-culture. An appreciation, British Journal of Criminology, 39 (2) 287–309.

-

Wathne, C. T. (2012). The Norwegian police force: A learning organization. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 35(4), 704–722.

-

Wieslander, M. (2016) Den talande tystnaden [The spoken silence]. Polismyndigheten: Polisområde Östergötland.

-

Withey, M. J., & Cooper, W. H. (1989). Predicting exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34(4), 521–539.

-

Wright, B. (2010), Civilianising the ‘blue code’? An examination of attitudes to misconduct in the police extended family. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 12 (3) 339–356.