Why Judicial Review?

Malcolm Langford

Senior Researcher, Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) and Co-Director, Centre on Law and Social Transformation, University of Bergen and CMI. Malcolm Langford is also a Postdoctoral at the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights and Pluricourts Centre of Excellene, Faculty of Law, University of Oslo.

Publisert 07.03.2017, Oslo Law Review 2015/1, Årgang 2, side 36-85

Abstract

Despite the flourishing of judicialisation of rights across the world, scepticism is not in short supply. Critiques range from concerns over the democratic legitimacy and institutional competence of courts to the effectiveness of rights protections. This article takes a step back from this debate and asks why should we establish or persist with judicial review. For reasons of theory, methodology, and practice, it argues that closer attention needs to be paid to the motivational and not just mitigatory purposes for judicial review. The article examines a range of epistemological reasons (the comparative advantage of the judiciary in interpretation) and functionalist reasons (the attainment of certain socio-political ends) for judicial review and considers which grounds provide the most convincing claims in theory and practice.

Keywords

- Judicial review

- rights

- legal and political theory

- constitutional theory

- international adjudication

1 Introduction

Why should we support judicial review? What factors should count in motivating a political community to establish or sustain an institutional practice that permit judges a final or authoritative say on questions of rights? Or, to put it in the language of normative legitimacy, what outputs does judicial review offer that might help overcome qualms over process concerns such as democratic representativity or policy distortion?

This question is, of course, not new. The voluminous debate on judicial review stretches back to the US Supreme Court’s iconic judgment in Marbury v. Madison in 1803 and, more locally, to a similar decision by the Norwegian Supreme Court in 1820. However, it is a question worth revisiting in light of ongoing theoretical contestation and contemporary legal developments. The question of why we need judicial review is never far from the minds of those engaged in constitutional reform processes and efforts to extend the adjudicative reach of international human rights regimes. If judicial review is to be defended, an interrogation and articulation of its potential value in general seems necessary at the outset. It is not sufficient to offer up a list of fine-grained mitigatory reasons that serve only to soften critiques. Moreover, establishing motivational reasons creates and frames the space for a serious encounter with different critiques: it ensures that the debate is not operating at cross-purposes.

This article begins in section 2 by considering why we should be concerned about the motivational question for judicial review. Section 3 provides a critical assessment of the epistemological claim that judges possess a comparative advantage in interpretation. Section 4 examines various functionalist arguments, in which judicial review helps secure certain socio-political ends. The article concludes with an assessment of which grounds are the most convincing.

A word on method. The question at hand can be answered on multiple planes. On the one hand, I situate each of the motivational claims and counter-claims within political and legal philosophy. Such arguments are highly stylised, possess numerous assumptions common to political philosophy, and use a largely moral calculus in assessing costs and benefits. On the other hand, the paper also plays the ‘science game’, to use Pinker’s depiction. Each motivational claim is assessed as to whether it is sufficiently consistent with: (1) theory from the social sciences about how actors actually behave; (2) empirical evidence of such behaviour from studies in law, political science and sociology; and (3) diverse national contexts. There is of course a clear limit as to how much theory, jurisprudence and empirical findings can supplement to a philosophical reflection. Nonetheless, I provide sketches and summaries in order to provide a much richer gloss on the validity of the morally-oriented arguments.

2 Judicial Review and its Critics

Why should we be concerned with the normative motivations for judicial review? There are at least three reasons. The first is theoretical: There is a tendency in the current literature to focus on epistemological arguments (both for and against) to the neglect of functionalist arguments which are more commonly found amongst practitioners. The second is methodological: being clear about the purpose of judicial review is crucial in navigating the various debates about the legitimacy, competence, and effectiveness of judges. The third is practical: reasons offered for judicial review appear to shape both its institutional reach and jurisprudential trajectory. Each of these justifications is briefly examined in turn.

2.1 Theoretical framing

Greater attention to the motivations for judicial review is necessary in the theoretical literature as certain reasons have dominated the discussion. Broadly speaking, it is possible to divide potential motivational grounds into two categories: epistemological and functional. Epistemological arguments emphasise the comparative advantage of the judiciary in interpretation. In divining the meaning and application of a particular right, courts are said to be more reliable in interpretive exercises than legislatures and executives. Functionalist arguments are epistemically modest although possibly more empirically demanding. It is not presumed that courts possess greater moral insight than other branches of government; rather, judicial review garners its institutional advantage through its socio-political function(s).

In the prevailing scholarship on the legitimacy of judicial review, epistemological reasons are endowed with a certain pre-eminence. In this universe of argument, we find methodological agreement between two of the most-cited bookends of the debate. Dworkin establishes the question as follows: ‘The best institutional structure is the one best calculated to produce the best answers to the essentially moral question of what the democratic conditions actually are, and to secure stable compliance with those conclusions.’ Likewise, this epistemic baseline stands central in Waldron’s critique of the substantive legitimacy defences of judicial review: ‘Outcome-related reasons, by contrast, are reasons for designing the decision-procedure in a way that will ensure the appropriate outcome (i.e., a good, just, or right decision)’.

This typology is not watertight. Both types of reasons can be nestled together. Ronald Dworkin often adds a functional claim to his epistemic one: ‘democracy requires that the power of elected officials be checked by individual rights’ and the ‘responsibility to decide when those rights have been infringed is not one that can be sensibly be assigned to the officials whose power is supposed to be limited’. Other authors offer coterminous and longer justificatory lists. Moreover, the claims can substantively overlap. To take Dworkin again, he sometimes asserts the interpretive advantage of the judiciary in more functionalist tones: judicial intervention is said to not only ensure, on balance, better answers but it also restructures public discussion about rights by foregrounding principled reasoning. Nonetheless, in legal and political theory epistemic reasons are often foregrounded, which suggests that we need a more critical analysis of this methodological choice. Moreover, these grounds are somewhat divorced from the functional and instrumental reasons that are commonly marshalled in practice for establishing the institution of judicial review.

Equally, we need to think carefully about which types of functional reasons should count and how. For instance, in a recent article, Fallon repeats the classical lines of a functional argument: Courts must possess the opportunity to invalidate legislation because the mere existence of legislation is likely to be more harmful to rights. Judicial review provides therefore a critical and additional veto check against such risks. However, as shall be seen, Fallon’s reasoning has been subject to significant critique on the grounds that it cannot account for the multitude of legislation that seeks to positively protect rights.

2.2 Methodology

A second reason for examining motivational reasons is the methodological role they play in debates over legitimacy, institutional competence, and effectiveness. For normative legitimacy assessments, it is common to weigh process against output reasons in establishing when a particular coercive institution is legitimate or not. In Waldron’s well-known critique of judicial review, its undemocratic features are weighed against its supposed epistemic outputs. Given his cursory approach to setting out the motivational reasons for establishing judicial review, it is possible that his balancing assessment might be different if a broader palette of reasons were included.

Similar cost-benefit or balancing approaches are taken in debates over the institutional competence of the judiciary. It is often asked whether judges should possess powers to review complex and polycentric issues, ranging from national security through to the allocation of limited budgetary resources. The concern is that courts risk distorting efficient and effective public policy. In addressing this tension, Jeff King sets up an expertise-accountability trade-off: the quality of expertise for a government’s position (institutional competence) is to be balanced against the risks to individual rights (accountability function of judicial review). Thus, when a State cites “collective” expertise (a position endorsed by a government agency/department, UN agency, or professional association) this ‘greatly skews the accountability trade-off towards deference to expertise’. However, King’s analysis privileges one functional reason for judicial review. As we shall see, there might be other grounds that justify judicial intervention when his trade-off favours strong judicial abstention or deference. Thus, the question is of relevance to the judiciary itself as it weighs competing factors in deciding when and how to exercise its discretionary powers.

A growing literature has also tracked the effects of rights adjudication. A key question in designing such research is determining what types of impact we expect from courts. The principal schools of thought have focused on either material impacts (changes in policies and social realities) or symbol and constitutive impacts (changes in politics and attitudes); although others straddle both camps. As Scheingold put it, ‘it is necessary to examine both the symbolic and the coercive capabilities which attach to rights’. To a large extent, this research is guided by an underlying normative debate on the legitimacy or usefulness of judicial review and public interest litigation. Yet, it is interesting to observe that there are fewer empirical studies on some of the normative reasons for adjudication analysed in this article, in particular the epistemic quality of judicial reasoning and the effects on deliberative reasoning.

2.3 Practical effects: A patchwork of judicial review

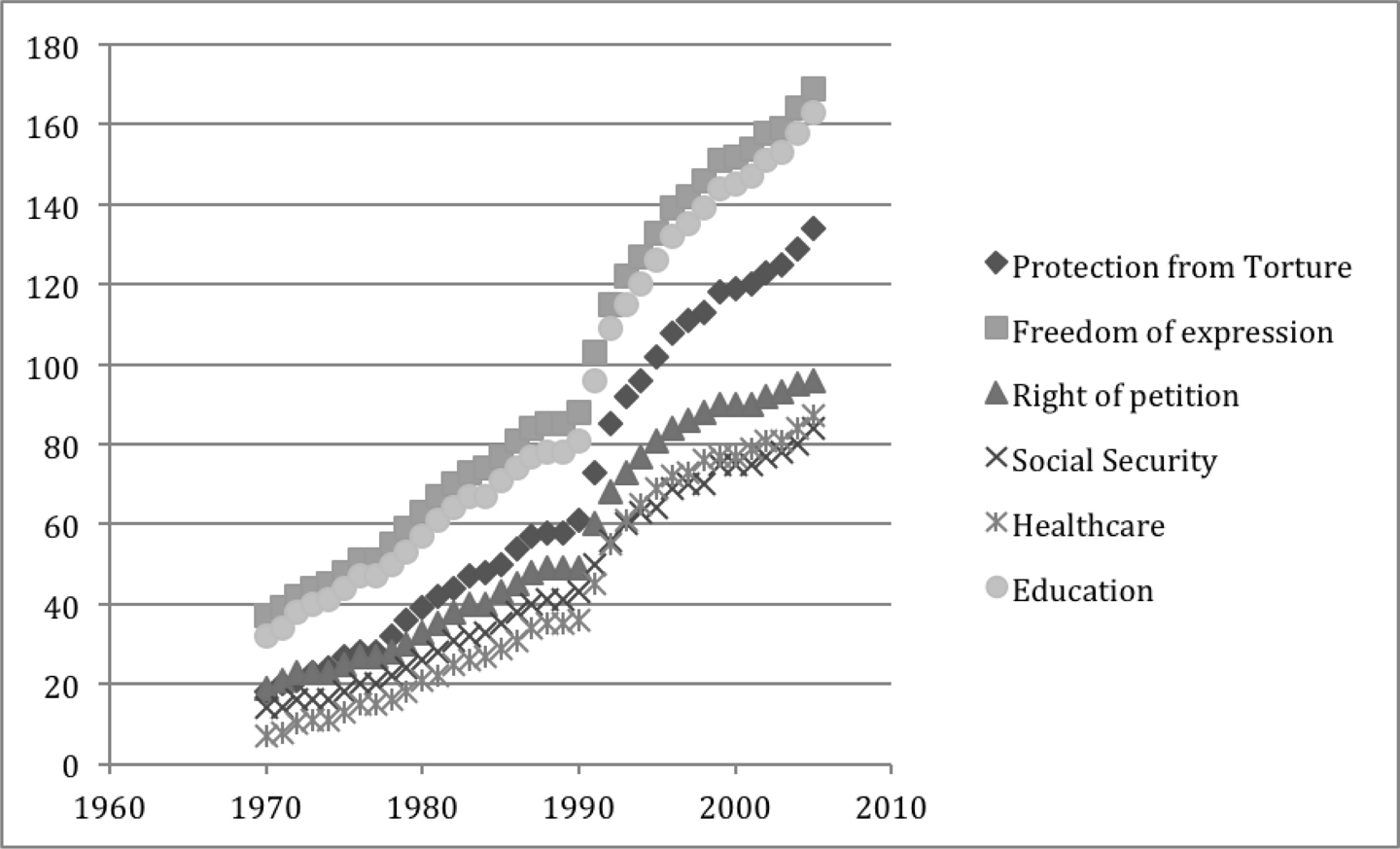

The final reason is that motivational grounds appear to affect the design and trajectory of judicial review in practice. On the one hand, the judicialisation of rights has flourished across the world in the wake of the Cold War. Numerous courts occupy an important and sometimes central place in the protection of constitutional and international rights. This transmogrification is evident in the constitutional reforms in a swathe of new democracies, constitutional renewal and heightened judicial engagement in older democracies (including Norway), and a spreading tapestry of international courts and complaint mechanisms. The twinning of electoral democracy with national and international judicial review constitutes a persistent feature of contemporary constitutional reform and practice. Exclusion of the latter from this equation is typically met with strong domestic and international protest. Further, there is an expansion of rights that are subject to review. From a limited number of narrowly framed civil rights, adjudicators are now ruling on a broader swathe of rights as well as duties. As Figure 1 demonstrates, there has been a remarkable and commensurate rise in the constitutional recognition of various civil and social rights.

Figure 1

Trends in Constitutional Rights: 1970-200531. The source of the original data is the CCP Data Set http://www.comparativeconstitutionsproject.org/. In order to transform it into times series data, it was determined whether for each year a constitution (dated by its most significant recent reform, usually at a time of democratic or post-colonial transition) included the particular right. As the recognition of some rights may be through earlier amendments to the constitution there is likely to be a margin of error. However, the overall trend is fairly clear.

Yet, this trend is not universal. The reach of judicial review does not extend to the four corners of the world. For a start, many Asian and Middle Eastern States cannot be found on this constitutional map: courts in these regions are granted fewer powers and are more tightly restrained, while international treaty protocols for individual complaints go unratified. For example, the average level of acceptance of international human rights adjudicative mechanisms is strikingly low for these two regions: 1.05 and 0.6 compared to 3.08 for the rest of the world. Yet, these States ratify substantive human rights treaties at a rate just below the global average. Conforming with Ginsburg’s observation of the emergence of national judicial review, the presence of electoral democracy is largely a necessary but not sufficient condition for explaining acceptance of international human rights review. While judicial review has emerged, sometimes surprisingly, in more authoritarian regimes, it is often highly fragile.

However, ambivalence is not constrained to regions that with a sizeable share of authoritarian and anocratic governments. In more mature democracies, constitutional reform processes have halted at the door of enhanced judicial review. Recently, in Norway, parliamentarians could not agree on formalising the Supreme Court’s powers of judicial review which it had claimed and exercised for 194 years. In Europe and Latin America, different coalitions of States have sought to weaken the powers of regional human rights bodies while the tribunal for the Southern African Development Community was stripped of its powers to consider individual complaints. Moreover, this uncertain picture of State commitment may be evident in assertions of patchy compliance with judgments, including by some Western European democracies.

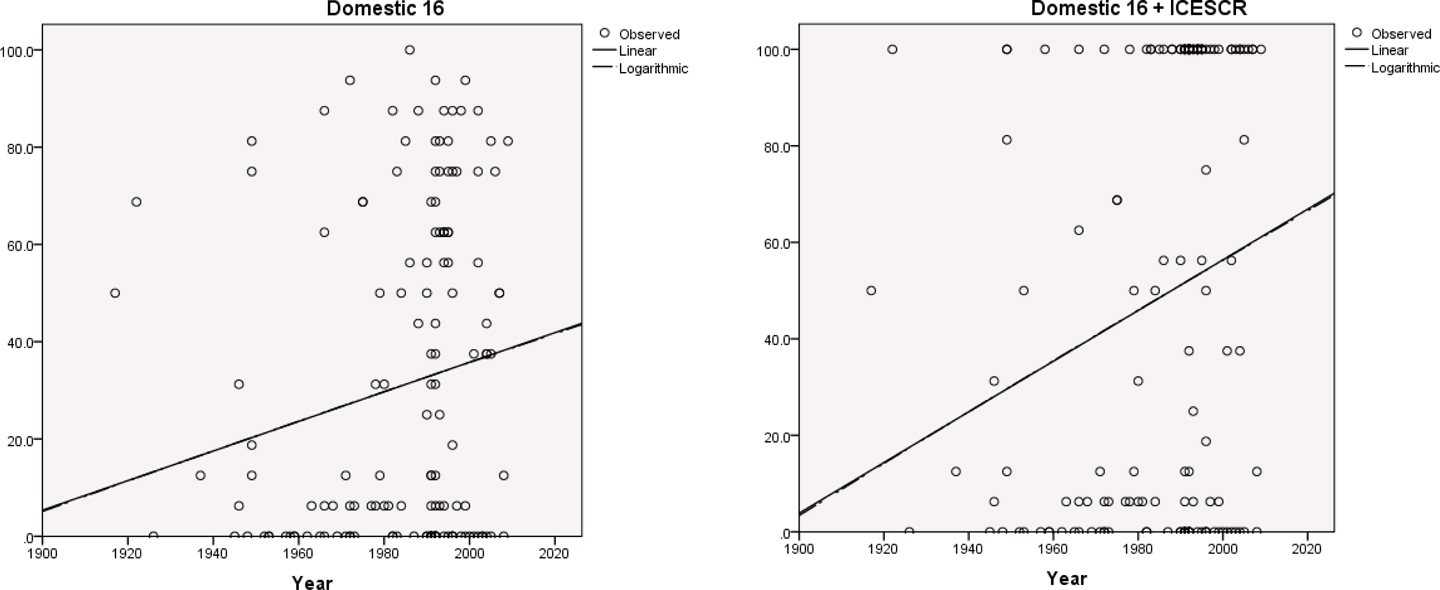

Jung and Rosevear argue that there has been a slowdown in constitutional recognition of judicial review of social rights. Noting the lower rate in the period 1990-2004 compared to the period 1974-1989, they suggest that the rise of the Washington-based consensus tempered recognition. However, this statistical and causal interpretation is questionable, and using the same data, Figure 2 reveals that the general trend line remains upwards. Nonetheless, what the graph does demonstrate is the equal persistence of the non-recognition of judicially enforceable social rights during recent constitutional reform. This was notable in Norway’s recent constitutional reform: The right to education and the social rights of children were included in a reformed bill of rights, but the right to health and adequate standard of living were rejected by a parliamentary super-minority.

Figure 2

Constitutional Recognition and ICESCR Incorporation over Time46. In Figure 2B, the year of constitutional adoption was presumed to be the year of ICESCR incorporation though this was adjusted in one case to a later date.

Does this patchwork of institutionalisation reflect normative differences over the importance or risks of judicial review? Explaining the rise of judicialisation is the subject of a growing body of empirical work. Thus, the fragmented nature of expanded judicial review suggests that normative dissensus remains a factor. It is not just a matter of time before policymakers, the legal profession and the entire public become accustomed to the idea; it is a site of deeper disagreement. This makes the march of judicial review less inevitable and more conditional on changes on ideas as much as politics and culture.

3 Epistemological Arguments

Epistemological justifications of judicial review tend to be the preserve of political philosophers, legal theorists, and lawyers. Like others, Michelmann sets up the inquiry as one of deciding which institution is able to ‘get the basic laws, including all morally telling interpretations of them, right’. Importantly, the question is usually phrased in relative rather than absolute terms. Which institution is most ‘likely’ to arrive at, or ‘better’ at arriving, the ‘correct’ or ‘true’ answer? In essence, it concerns the reliability of interpretation.

The clear challenge for epistemological claims for judicial review is the existence of reasonable disagreement. Rights are a quintessential “under-theorised agreement”, permitting a range of plausible interpretations. In hard cases, this interpretive ambiguity is put to the test. As Tushnet states:

[C]onstitutional provisions are often written in rather general terms. The courts give those terms meaning in the course of deciding whether individual statutes are consistent or inconsistent with particular constitutional provisions. But as a rule, particular provisions can reasonably be given alternative interpretations. And sometimes a statute will be inconsistent with the provision when the provision is interpreted in one way, yet would be consistent with an alternative interpretation of the same provision.

To compound matters, interpretive differences are not confined to disagreement between the different branches of government. Judges can be divided amongst themselves: synchronically (majorities, minorities, and separate opinions), hierarchically (differing views between upper and lower courts), or diachronically (reversal of earlier decisions).

The odyssey of Sherbert v. Verner in the United States exhibits dramatically all three features. In the case, a South Carolina government agency refused to grant unemployment benefits to Mrs Sherbert, a member of the Seventh Day Adventist Church. While local job opportunities were available, she claimed that such employment was not possible because it required working on a Saturday, the Sabbath in her religious denomination. By a majority of 7 to 2, the US Supreme Court held in its 1963 judgment that a law or rule which substantially interferes in effect with the free exercise of religion can only be justified on two grounds: it constitutes a ‘compelling state interest’ and no ‘alternative forms of regulation’ are available. Applied to the facts, they found in favour of Mrs Sherbert.

The doctrine stood for 27 years but in 1990, the same court, by a majority of 5 of 4, loosened or abandoned the strict scrutiny test in Employment Division, Department of Human Resources v. Smith. In overruling the Oregon Supreme Court, which had found that the use of the drug peyote in a Native American church ritual could not constitute grounds for employment dismissal and the subsequent denial of unemployment benefits, they found that interferences were only invalid if imposed with the intention of harming religion. In effect, the Court confirmed the alternative logic and interpretation of the original Sherbet dissenters.

Beyond revealing intra-judicial disagreement within courts, across courts, and over time, the case reveals even more about the extent of the disagreement. First, the US Congress emphatically disagreed with the 1990 decision and passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (unanimously in the House and by 97 to 3 in the Senate). Yet, in a subsequent ruling, the US Supreme Court partly overturned the Act on the basis that Congress sought to usurp the Court’s interpretive power over the constitution. Secondly, the diachronic direction of judicial disagreement was not predictable. It is often assumed that courts are unidirectional and dynamic, such that rights protections expand over time. Here, the right to religious freedom was significantly curtailed by the Court and its greatest impact appears to have fallen on minority religions: Judaism, Islam, and Native American religion. Thirdly, the form of legal reasoning was not foreseeable. Predominant legal theories of interpretation did not correspond with their protagonists in the Court. The most famed originalist, Scalia, devoted not a hairbreadth of analysis to the intention of the Framers of the US Constitution. Rather, he placed great weight on contemporary circumstances and the turmoil the Sherbert rule would create in a society characterised by religious diversity. It is the dissenting minority that invokes the originalist claim, along with other arguments, and it is Justice Blackmun who returns to the struggle of the founding fathers to win and constitutionalise religious liberty.

Such puzzling dissensus also extends to the international level. The European Court of Human Rights and UN Human Rights Committee have divided along similar lines on religious freedom. In one instance, they came to dramatically different conclusions concerning the same applicant and the same issue. In Mann Singh v. France, the Court found a challenge to the prohibition on the wearing of a turban in a driver’s licence photo to be a ‘manifestly ill-founded’ claim. Yet, the Human Rights Committee in (Mann) Singh v. France, found a violation of religious liberty for a ban on the use of a turban for a passport photo. It held that the State’s objective of identification for public safety was irrational. If the applicant always wore a turban, a “turban-less” image would not assist officials wishing to identify him.

This extended vignette on religious freedom exposes reasonable disagreement in its different forms in the variegated and shifting landscape of judicial review. In the two dominant doctrinal approaches surveyed, strict and deferential review on religious interference seem reasonable on first blush. Although the former is clearly more protective of individual rights, the ebb and flow of these cases seem to raise real questions over the comparative advantage of the judiciary.

Isolated cases, however, do not hammer nails into the coffin of an argument. The epistemological claim is more measured: judges are more likely to arrive at a better interpretation. Such a strategy permits a proponent of judicial review like Dworkin to both defend the institution and criticise individual judgments, particularly those of the current U.S. Supreme Court. While conceding that judges will ‘inevitably disagree’, he asserts that the reasoning of the present majority in a range of decisions ‘cannot be justified by any set of principles that offer even a respectable account of our past constitutional history’. The move also allows Dworkin to maintain his notion that almost all cases will contain the “right” or “best” answer, even if only discernible by a Herculean superjudge.

Nonetheless, this strategy does not address the methodological challenge. Can we be sure that courts will more consistently arrive at better interpretations? And, if so, under what conditions? The problem is that there is no clear and agreed upon aggregative metric or ruler that we can put under constitutional interpretations of courts, legislators, and executives to determine which is the most epistemologically reliable. The most effective route is arguably longitudinal qualitative and partly quantitative analysis, which may reveal the underlying motivations of different actors and the wisdom of their considerations. The problem is that one is usually reduced to tracing individual or small samples of interpretations; and one can find courts and legislators behaving badly (and decently).

Proponents of judicial review tend not to travel too long down that path. Rather, they point to certain defining features of judicial review that suggest that courts will arrive at better answers. It is a “forward-looking” method that presumes “favourable conditions” generates “a good outcome”. We can categorise these as the: (i) authenticity of case-based review; (ii) the semi-public mode of deliberation; and (iii) the form of decision-making. Each will be examined in turn. These epistemic arguments may be compelling but deserve close consideration. They all draw on particular institutional attributes of courts, and as the legal process school in particular has sought to emphasise, institutional features may not consistently correlate with the quality of judicial reasoning.

3.1 The authenticity of case-based review: Evidential particularism

A commonly-cited epistemic advantage of judicial reasoning is its factual palette: the particularity and authenticity of concrete cases. The argument runs that legislative and executive reasoning tends to be dominated by general and stylised considerations. Yet, at least in the field of individual rights, such reasoning may be less appropriate, occluding the practical and problematic effects of rules (or lack thereof) on disparate individuals. Bilchitz sets out this critique of legislatures in customary fashion:

General decision-making across a range of cases can obscure the problems that may arise in particular instances to which that general decision may apply. General decision-makers may simply overlook or fail to give sufficient weight to the problems that may be faced in particular cases.

The claim is alluring enough. It resonates deeply with the defence of judge-made common law in Anglo-American jurisdictions. Rules and principles develop and mature best through the inductive and analogical reasoning of courts in actual cases, avoiding the ‘perils of prophecy’ through a ‘long course of trial and error’. In rights jurisprudence, the scenario is common enough. A law may be highly defensible on general grounds, but its impact falls disproportionately, whether unfairly or unwittingly, on particular individuals or groups. Video surveillance, efficient criminal trials, religious education, conditions for unemployment benefits and so on may constitute positive public aims, but their consequences are unlikely to impact individuals in a uniform manner.

Nonetheless, there are serious problems with this argument (putting aside its somewhat anti-democratic overtones). First of all, it is equally possible to encounter the reverse scenario. Laws may be motivated by very particular situations without regard for their general and systemic effect on rights. A terrorist bombing, the abuse of social benefits by one family, an alleged rape by a member of an ethnic minority, a surge in homelessness in urban business districts, may all trigger legislative solutions that possess no generalised justification or grounding in empirical reality. In these circumstances, we would want courts to lift rather than concentrate the perspective. Thus, we may wish to fully reverse Bilchitz’s position and ask whether the legislature has properly engaged in ‘general decision-making across a range of cases’ and evaluated the systemic impacts of rights, which may be represented (not just actualised) by an individual in a legal case.

It might be retorted that over the last two centuries, the degree to which legislation is targeted at such specific groups has waned in mature democracies. Nonet and Selznik describe a general shift from repressive legal regimes to autonomous and responsive law. Repressive law is concerned the maintenance of order and selective subordination in the interests of the rulers and elite, while autonomous law offers impartial, neutral, and equal treatment and responsive law attends to the needs and values of the disempowered and disadvantaged. But vestiges of repressive law persist and its potency remains latent. Every policy narrative requires an “enemy” and, even when law and politics are framed in autonomous terms, repressive motivations may be observable if not transparent.

A good illustration is A & Others v. Secretary of State for the Home Department. The September 11 bombings in New York led the British parliament to embellish its fresh and comprehensive Terrorism Act of 2000. Foreigners could be detained and deported if the relevant government minister believed they were a risk to national security and suspected their involvement in international terrorism. The provision created a “prison of three walls”: detainees could voluntarily leave for their home or third country. Yet, if they did not or could not due to fears of torture, detention would continue ad nauseum. While passing the law, the government sought to immunise it from challenge by making a derogation order from rights to liberty and security in the European Convention on Human Rights on the grounds of a public emergency.

The primary question for the House of Lords was not whether a general rule had particular effects. The law was all about particularity: its force was trained on a particular group – to which all eleven defendants as foreigners belonged. Instead, the court was confronted with three general questions: Was there a public emergency justifying the derogation? Was the legislation proportional to its aim? Finally, was it discriminatory against foreigners? The majority sided, somewhat reluctantly, with the government on the first question on the grounds that, in determining the existence of a public emergency, the executive possessed greater institutional competence and benefitted from a wide margin of appreciation. Yet for the rest, the answer was negative. The legislation failed the proportionality test. The use of immigration measures was unlikely to advance the stated security goals: deportees would still be free to plan attacks against the UK, as would nationals. It was also discriminatory: no reasonable and objective criteria existed for imposing harsher treatment on non-nationals given the considerable number of British citizens involved in or suspected of international terrorism.

Of relevance are the considerations that were weighed. The particular circumstances of the defendants did play a role: the court took seriously the consequence that innocent foreigners could be held incommunicado ad infinitum. However general considerations were equally important in the proportionality test, and ultimately decisive. They revealed an inconsistency between the legislative measures and the stated aims. Not only was the law difficult to square with the need for generalised equal treatment, the law, as one commentator put it, made ‘no sense in security terms’.

Secondly, even if we persist with the individualist perspective, it may be empirically limited. The particularity justification may be just that - rather particular to Anglo-American jurisdictions. Not all constitutional and international rights cases arrive in the form of individual complaints. The form of judicial review varies significantly. Adjudicators in many jurisdictions are granted the power to abstractly review legislation, issue advisory opinions, and entertain complaints by legislators or collectives/organisations. These powers are particularly prevalent in civil law jurisdictions, while liberal standing rules in some common law countries permit public interest complaints. The latter two powers exist in regional quasi-judicial procedures and the final in some southern common law countries, particularly South Asia. To varying degrees, the production of factual evidence and evidence of particular violations is required, but it may not be central to the case. Moreover, some adjudicatory bodies may launch investigations and inquiries.

It might be objected that this criticism is unfair. Not all defenders of judicial review support abstract or collective forms of review. In their view, a lack of particularity may deprive the claim of legally manageable content or the meaningful context for the interpretation and application of a right. This is partly true. The individualised structure of much judicial review does carry certain benefits, although perhaps more of a functional than epistemological kind. But collective forms of review offer complementary benefits. As will be argued later, it can ameliorate the critique that rights are too individualised in their focus, capture the collective dimension embedded in most rights, provide broader guidance and legal certainty to the meaning of particular provisions and allow courts to rule on important questions when individual applicants are pressured to abandon or settle their claims.

Waldron goes a step further and labels the particularist virtues of Anglo-American courts a mere ‘myth’. In appellate review, the traces of ‘the original flesh-and-blood rights-holders’ have “vanished” as the argument becomes more abstract. According to him, complainants are selected by advocacy groups ‘in order to embody the abstract characteristics that the groups want to emphasize as part of a general public policy argument’. This critique is pertinent though overstated. In the common law world, the factual record from lower courts is left largely intact (although it can be more easily contested in civil law jurisdiction). Moreover, while public interest advocates do try to identify more sympathetic claimants and narratives, their degree of control over litigation can be marginal.

Yet, Waldron is right in pinpointing the generalised element of judicial review. In 1976, Chayes identified this feature as a particular turn in civil law from that of retrospective and bipolar litigation dominated by individualised remedies to the more forward-looking model of public law characterised by multiple parties, a more predictive and evaluative approach to fact-finding and the presence of structural or general remedies. The Chayesian paradigm shift is of course highly stylised. It ignores the long tradition of these general features in private law the fact that that most public law cases are modest in ambition or concern individualised administrative remedies. However, Chayes is most likely correct that general considerations may be more prominent in cases that seek ‘vindication of constitutional or statutory rights’ rather than ‘private rights’.

To sum up, the particularity of judicial review may give the courts a slight epistemic advantage over legislators and executives. Though if adjudication can and should concern broader principles and policies, questions remain over a judicial comparative advantage on this terrain, as we shall see in section 2.3. Two further factors may ground such a claim.

3.2 A semi-public deliberation: Informational exposure, decisional seclusion

Adjudication is a unique institution on account of various structural features which work in opposite directions. In theory, the judiciary is fully exposed to an array of arguments and facts but is secluded from political pressure, permitting it to make non-partisan or principled decisions. An adjudicator is an extroverted perceiver and an introverted decision-maker, making them sensitive to conflicting accounts but independent in judgment.

The first characteristic is a hallmark of deliberative democracy theory. Robust exposure to different views is said to produce better decision-making. Michelmann sets up the question as to comparative epistemic advantage as follows:

(O)ne condition that you think contributes to greatly to reliability is the constant exposure of the interpreter – the moral reader – to the full blast of the sundry opinions on the question of rightness of one or another interpretation, freely and uninhibitedly produced by assorted members of society listening to what the others have to say out of their diverse life histories, current situations, and perceptions of interest and need.

Even though evidence from empirical research on deliberative democracy suggests that these assumptions have limits and defects, we can accept for the moment that interpretive reliability improves with full argument and informational exposure. The question is whether courts possess any particular comparative advantage, structurally or in terms of the different incentives and costs different actors possess in accessing information.

The second structural characteristic of judicial deliberation is the requirement of impartiality and independence. The political insulation of the courtroom may allow dispassionate, and consequently better, reasoning. Sibley argues that conduct can only be ‘deemed reasonable by someone taking the standpoint of moral judgment’ and this often requires the intervention of a third party:

To be reasonable here is to see the matter – as we commonly put it – from the other persons point of view, to discover how each will be affected by the possible alternative actions; and, moreover, not ‘merely’ to see this (for any merely prudent person would do as much) but also be prepared to be disinterestedly influenced, in reaching a decision, by the estimate of these possible results.

These features of informational exposure and decisional seclusion can be captured within a principal-agent model, as done in effect by Kis. We begin by asking why political authority is delegated first from the people to elected representatives. In Kis’s view, most mature democracies prefer a system of electoral democracy over direct democracy because ordinary citizens face challenges in obtaining relevant information. Condorcet’s jury theorem – that a majority is more likely to get the right result than a minority - does not work at scale. Referenda generate few incentives for citizens to become fully informed since the weight of their respective vote is so small: it approaches zero as the population becomes large. Bentham made precisely this exact point in 1788: ‘the greater the number of voters the less the weight and value of each vote, the less its price in the eyes of the voter, and the less of an incentive he has in assuring that it conforms to the true end and even in casting it all’.

Thus, the greater the complexity of the issue and the more information needed the ‘more serious the danger that the voters’ judgment will not be just unreliable but subject to some systematic distortion’. On balance, Kis concludes that representative institutions have an epistemic advantage over citizens. The costs of accessing and processing information is low (due to economies of scale, research staff, and bureaucratic channels) and the incentives are high (better deliberation could produce more votes). The result is that the main tool citizens possess in a democratic process is one of accountability, namely periodic elections: it ‘permits the citizenry to remain sovereign while paying obedience and commands issued by a representative assembly’.

With the rise of complexity in modernity, this account has a certain resonance. According to Stone Sweet, enhanced complexity generates a demand within dyadic relations (two entities) for more triadic forms of governance, by parliaments, executives, and judiciaries. It also coheres with certain empirical research. Hibbing and Thiess-Morse note the paradoxical positions of voters in surveys and focus group studies. While participants expressed a preference for significant control over decision-making, few expressed a preference for strong direct democracy. They warmed initially to the idea of direct rule but quickly raise feasibility concerns, many of them related to complexity and lack of information. Such research does not rule out a role for direct democracy - it is arguably a powerful means to catalyse and tame rather than manage and direct the political process - but it reveals the limits to its contribution and support.

Returning to Kis, this comparative advantage of legislators over citizens can nonetheless generate its own perverse effects. The asymmetry of information between the elected and the electors invites the more “predatory” politician to adopt ‘mistaken electoral beliefs’ in order to avoid electoral defeat. If rights are affected, this is serious ‘because collective self-government depends on each citizen being treated as an equal’. As citizens in most jurisdictions lack direct levers of control over the judiciary, the risks of the judiciary falling prey to this moral hazard is comparably less. Thus, the very feature that makes courts susceptible to charges of democratic illegitimacy may strengthen their epistemological capacity.

It is not too difficult to identify cases in which courts correct predatory information asymmetries. In the seminal prison litigation cases in the USA, it was strikingly revealed. Until the 1970s, all branches of government in the State of Alabama had declined to address prison conditions; there was clearly no electoral gain in addressing the problem. While courts had acted traditionally in a highly deferential manner, it was the instigation of litigation in 1971 that eventually permitted a full and public description of prison conditions, a system ‘so thoroughly pervaded by violence, overcrowding, inedible food, and brutal methods of punishment’. The force of the evidence was so strong that even the state’s attorney general conceded that they had no case to advance. The entire prison system was ruled unconstitutional. A cursory reading of the European Court of Human Rights judgments on police brutality and prison conditions in Western and Eastern European States makes for equally salutary reading.

Moral hazard, though, is just one feature of informational asymmetry. Kis could have strengthened his case by an analysis of both the resource and time constraints and disincentives to deliberate that representative institutions face. The deliberative democracy school emerged precisely due to the concern that legislatures lacked the willingness or capacity to meet deliberative criteria, such as reciprocity (providing mutually acceptable reasons), publicity (a sufficiently open forum) and accountability (deliberating with and giving reasons to relevant agents). The reasons for this informational asymmetry are practical and structural.

Practically, there is a limit to the time legislators can devote to reflection, deliberation and constituent consultation; and staff and bureaucrats may be unable to generate sufficient or quality analysis on the topic. In most parliaments across the world, there is an enormous volume of legislation and regulation that must be accommodated. Modern parliaments operate therefore under severe time constraints and strictly regulate the time spent on debating legislation.

Structurally, legislatures are not designed for public deliberation but rather for the creation and maintenance of legislating and/or governing majorities and, depending on the political conditions, the aggregation of citizen preferences. There is no reason why public deliberation should be the dominant modus of legislative reasoning: negotiations, deals, threats etc. are all part of the political modus. Moreover, ‘If a representative is guided by factional or short-term interest, no amount of deliberation can induce an impartial stance’. Scholars have pointed to deliberative paradox thrown up by legislative processes: if discussions occur publicly, parties may be more likely to harden their bargaining position which defeats the point of genuine deliberation.

The combination of these constraints and incentives are evident in practice. Reviewing literature on European parliaments, Rasch concludes that:

In general, plenary debates on legislation in assemblies of (at least) parliamentary systems tend not to be deliberative. Arguing seldom affects information and preferences in a way that become important at the final voting stage. Outcomes almost always are known in advance…. Instead, it is much more common for legislators to use plenary debates as an arena for stating their reasons, revealing their preferences and explaining their vote – primarily to outside party members, media and the general public.

This finding contradicts claims by judicial review critics such as Waldron who praise legislatures as paragons of deliberation. Waldron writes, ‘In this regard, it is striking how rich the reasoning is in legislative debates on important issues of rights in countries without judicial review.’ Yet, his only example is a debate on abortion in the British parliaments from the 1960s. Also, he fails to reconcile his own normative perspective with his own empirical observations: he has bemoaned earlier the lack of debate in the New Zealand parliament, characterising it as an ‘empty chamber’.

Overall, this quasi-deliberative claim for courts is attractive. In the context of fully fleshed-out litigation, a court may be exposed to a greater volume of relevant information and informed expertise and address these in a disinterested and thoughtful manner. However, there are four significant caveats.

First, not all cases are complex. Kis acknowledges for instance that complexity may not loom large for the general public on some issues, particularly issues of ‘personal morality’. He names capital punishment, gay marriage or affirmative action since ‘people have the opportunity for acquiring shared experience’. This fact may explain why both laws and jurisprudence on these issues arouse significant controversy, and both legislators and courts risk charges of elitism. Nonetheless, even here, Kis notes the importance of information. Judicial intervention may help deepen the understanding of the causes of inequality, which may be needed in order to assess clams for affirmative action or gays and lesbian rights, particularly if one has had no interaction with the persons who would benefit from the law.

Secondly, the informational advantage of courts is both conditional and contextual. Legislative and executive members can avail themselves of information and expertise from parliamentary committees, public consultations, in-house legal expertise and closer attention to mass media, while the significance of predatory political behaviour for rights may vary considerably. As to the adjudicatory process, it possesses its own in-built constraints: significant time and resources can be consumed by procedural machinations and cases vary considerably in terms of exposing courts to a full range of opinions and facts. Indeed, the strictures of legal method and argument may screen out morally relevant information and arguments (see further discussion in section 2.3). Moreover, while adversarial litigation generally allows weaker parties a chance to more fully put their case, alternative or more fine-grained opinions may not secure a hearing unless there is a good process for amicus curiae briefs, expert opinions and media/public exposure of on-going litigation.

Thirdly, exposure does not equate to comprehension. What is missing in Kis’ account is the differential capacity of both institutions to process complex information. Judiciaries are not experts across all policy domains and face, like any institution, their own challenges with complexity. The trend towards expert decision-making agencies is unmistakable. As will be argued in the next sub-section, the judiciary is adept at expanding their expertise within cases and over time, but one cannot overstate their capacity.

Fourthly, the assumption that courts are independent from politics is contested. Decades of empirical research on judicial behaviour demonstrate that legal reasoning is only one factor in decision-making. Indirect political pressures or personal ideology may compromise judicial independence. The extent to which judiciaries are independent will be taken up later, but for now it is important to note the dilemma.

3.3 The mode of decision-making: Justification and method

A final epistemic advantage may arise in the mode of judicial deliberation: the form and substance of reasoning. As to form, judges must State their reasons. For those obliged to provide public and written justification, certain expectations are common: a logical and defensible progression of argument; a demonstration that relevant facts and competing views have been considered; and awareness that the decision has consequences. Conversely, it might be thought that other branches of government are not so formally constrained. Legislation is passed without any formal process that demands coherent and rigorous reason giving.

This argument has merit but, ultimately, its force is modest. Empirically, not all courts are compelled to provide reasons. Judges in some civil law jurisdictions (e.g. France) provide scant reasoning: authority is presumed to flow from hierarchy and the proper operation of the legal process. Such a result is consistent with the centralised ordering of the civil law judiciary with rigorous internal systems for maintaining legal consistency across decisions. This is to be contrasted with the decentralised and coordinate common law systems. Individual judges possess enormous powers that must be justified publicly to political actors and other members of the judiciary: reasons emerge as an important form of accountability.

However, one should not overstate the discrepancy between legal systems. In some instances, it a difference in style: e.g., Germanic-influenced courts prefer a highly deductive and impersonal style of form and reasoning. Moreover, there is considerable intra-jurisdictional borrowing in the contemporary design and reform of judicial systems. In particular, the rise of constitutional and international rights review has prompted courts lower in the chain to be more expansive in their statement of reasons. Otherwise they risk being perfunctorily overruled. The European Court of Human Rights has demanded that on certain topics reasons must be given or easily discernible from judicial findings (such as determination of criminal guilt). The Court’s justification of its position is apposite in highlighting the reason-centric focus of legal process:

[F]or the requirements of a fair trial to be satisfied, the accused, and indeed the public, must be able to understand the verdict that has been given; this is a vital safeguard against arbitrariness. As the Court has often noted, the rule of law and the avoidance of arbitrary power are principles underlying the Convention … In the judicial sphere, those principles serve to foster public confidence in an objective and transparent justice system, one of the foundations of a democratic society…

Turning to the legislative side of the equation, we should ask whether legislatures experience analogous opportunities, pressures, and incentives to state reasons. Further, do they develop reason-giving cultures over time? Structurally, there are grounds for thinking so. Legislation is debated in parliament, often in repeated phases. Justification for positions on at least particularly controversial issues will be demanded by the media, constituents, opposition politicians, and possibly more diplomatically by bureaucrats. The result is that the legislative record can contain substantive reasoning. In four case studies of constitutional questions in legislative debate, Tushnet draws back the curtain to reveal a certain level of reason-giving, such as legislative attention to constitutional rights, parliamentary committees which scrutinised legislation, and the expansion of legal advisors within the executive and legislative branches. From this he draws the conclusion that ‘the performance of legislators and executive officials in interpreting the constitution is not, I think, dramatically different from the performance of judges’.

However, the argument in favour of legislatures can be taken only so far. First, as discussed earlier, there are constraints and incentives that operate to restrict the level of deliberation. These are part of the calculus of legislators. Secondly, the statements of reason tend to be thin. Tushnet argues that sometimes there is ‘flesh on the bones’ in legislative debates, but he acknowledges that most of the times the reasoning constitutes ‘skeletons’ of argument. While he counter-asserts that this is not much different from the verbal discussions between justices, the fact is that judges are at least required to set out those reasons. Even if they may be a rationalisation of intuitions, according to the legal realist tradition, they must be transparent. They can provide the basis for substantive discussion, occasionally in the media but at least amongst the contesting parties, policymakers, politicians and the legal profession.

These considerations might lead us to count the stating of reasons as a slight form of epistemic advantage for courts. However, we have only considered form. We must also ask a more substantive question: do the methods used by courts produce more reliable interpretations? This is a much more difficult challenge. And, it is at this point, that the twinning of moral and legal epistemological arguments for judicial review splinters, twists, and potentially falls apart.

The legalistic reflex is to defend the method of judicial reasoning by reference to doctrinal expertise. In interpreting constitutions and treaties, judges are more likely to follow an established legal method as the relevant legal system dictates: placing the correct weight on legal text, precedent and practice, principles and theories, case and background facts etc. Yet, this very modus of reasoning may count against the courts. If the metric for reliability is good moral reasoning, recourse to legal method may demonstrate precisely why we do not want courts to be given the task of rights interpretation. As Waldron puts it, judicial review does not provide ‘a way for a society to focus clearly on the real issues at stake when citizens disagree about rights’ but rather ‘distracts them with side-issues about precedent, texts, and interpretation’. He notes, however, that in contemporary constitutions, the gulf between quality moral reasoning and acceptable legal reasoning may not be as great.

This framing presents a sharp choice: If the case for judicial review rests on quality legal reasoning, it is open to the normative charge that it may be poor moral reasoning. If the case rests on quality moral reasoning, it is open to the empirical critique that the reasons judges give must be more legalistic in nature. It seems one has to choose.

Yet, some critics would not even allow that. They would go even further and claim that the first choice is fallacious: courts are not engaged in anything that can be substantively identified as legal reasoning or method. Courts are principally guided by moral and political convictions rather than any objective or external legal criteria. Stated legal reasons are but a subterfuge. Thus, one is only left with an argument from the standpoint of moral reasoning and that is likely to be weak if the official legal reasons are covering unstated moral preferences. This critique is overdriven. No one school of thought has empirically explained judicial outcomes as discussed above. Gibson’s observation from 1983 seems to stand the test of time:

In a nutshell, judges’ decisions are a function of what they prefer to do, tempered by what they think they ought to do, but constrained by what they perceive is feasible to do. Thus, judicial decision making is little different from any other form of decision making. Roughly speaking, attitude theory pertains to what judges prefer to do, role theory to what they think they ought to do, and a host of group-institution theories to what is feasible to do.

Nonetheless, the realist or attitudinalist point demonstrates, at least, that one has to be cautious in resorting to legalistic defence of interpretive method.

How can the argument be saved? There are at least three ways forward in trying to re-scramble the egg of law and morality. The first and most common way forward is to limit the scope of the claim to a subset of areas where the two clearly overlap. The legal process school, among others, argues that the articulation of rights and duties should be limited to those areas where the judiciary has institutional competence. In Lon Fuller’s classic treatment of institutional competence, adjudication is positively viewed as contributing a distinct form of decision-making to public policy: ‘a form of social ordering institutionally committed to ‘rational decision’ that is based on ‘participation through proofs and arguments’. However, judges are likely to make mistakes in adjudicating in areas where they must access information not presented by parties or that trigger complex and polycentric repercussions of a judgment. This consequentialist argument fits neatly with some liberal arguments that judicial review thus should be limited to negative liberty rights. Therefore, we might be more comfortable that courts will be more reliable in these sorts of cases.

However, the argument struggles on various points. Most of the controversial cases discussed in this piece have involved classical liberty rights. Such a demarcation of competence may be arbitrary or a mere historical reconstruction. In addition, courts have developed various techniques to improve their access to information and expertise in more complex cases, from amicus curaie submissions through to experimental and reflexive doctrinal techniques and remedies. Such approaches seek to maximise the respective competences and contributions of the courts and other branches of government to solving a problem.

A second and alternative way forward is to embrace the standard of moral reasoning and contend that courts are superior in this respect. Dworkin does this in four moves. First, he argues that in practice lawyers and judges ‘instinctively treat the Constitution as expressing abstract moral requirements that can only be applied to concrete cases through fresh moral judgments.’ Secondly, while he concedes it would be ‘revolutionary’ for judges to make such a concession, he argues that this moral approach largely fuses with legal method. This is because basic legal rights are framed in abstract moral terms: treating them as moral rights constitutes the only sensible means of legal interpretation. Thirdly, he contends that moral reasoning on rights must be based on principles rather than policy: there must be “distributional consistency from once case to the next” because rights ‘do not allow for the idea of the strategy that may be better served by unequal distribution of the benefit in question’. Finally, courts as a “forum of principle” are better placed for such a task. They are constrained by ‘articulate consistency’: Legislatures and executives are likely to give undue weight to policy considerations due to their orientation towards the advancement of “general welfare”.

Dworkin’s defence of courts as forums of principle is compelling in the abstract but is practically limited. His later model of “law as integrity”, which embeds judges more firmly in their legal context (Anglo-American although potentially exportable to civil law systems), places a constraint on principle-based reasoning. In the “chain gang”, judges are both backwards and forwards-looking: seeking to both fit their chosen principle with previous interpretations and the best available and contemporary moral interpretation. Such coherence may not always be achievable. As the Sherbet saga showed, judges are likely to possess different preferences for weighing the past and future. A further constraint is Dworkin’s acknowledgement that rights can be relative as much as absolute: they are not always full trumps: sometimes, policy considerations will be strong enough to dominate. The necessary weighing of arguments raises the question of judicial expertise, their capacity to determine the weight or force of policy considerations, something Dworkin does not address yet is common in almost all rights cases.

Dworkin’s best case seems to be that courts will generally give more weight to moral principles but that legal precedent and policy considerations may sometimes dominate. Even if we accept this argument, it is not patently clear that it amounts to the most compelling case for judicial review. Dworkin’s approach ends up mirroring the sorts of claims by the legal process school – that judges are expert in one type of approach. In this case, it is principles rather than discrete cases.

However, if courts are called to also assess various policy considerations, we should expect them to be up for this task. This provides a third way forward. What is notable in the religious freedom and counter-terrorism judgments discussed above is the presence of significant consequential reasoning by courts - their close scrutiny of the policy-based claims of governments. However, the overall picture is different from Dworkin’s: courts emerge not so much as forums of principle, with immaculate moral reasoning, but rather as forums of principled pragmatism. It is a mode of reasoning well summarised and promoted by Carter and Burke. They argue that ‘well-reasoned legal decisions’ are those fit best together ‘the facts established at trial, the rules that bear on the case, social background facts, and widely shared values’, rather providing epistemic clarity: ‘Law does not provide a technique for generating “right answers”’.

If principled pragmatism were the standard, how would courts perform? Most parliamentarians and ministers also aspire to be principled pragmatists - marrying value or ideological commitments with complex reality. Given that rights tip the balance in favour of principled reasoning, we might expect generally courts to have some epistemic advantage. However, some of the cases discussed above suggest that courts can be superior in consequential reasoning and inferior in principled reasoning.

3.4 The limits of epistemological justifications

Are courts better placed to interpret rights? Of the various arguments traversed above, the strongest arguments for adjudicators are their political seclusion and their bias towards principled forms of reasoning. Their relative freedom from partisanship and the demands of coherence seem particularly to enhance the prospects of reliable interpretation, at least legally and possibly morally. Epistemological reliability might be enhanced further when courts are better exposed to the particularities of alleged rights violations, are able to secure a broad evidential and informational base, and are required to state fully reasons.

Nonetheless, none of these features provides a knockout blow. On balance, courts emerge with some sort of prima facie interpretive distinction, but how significant is it? Moreover, will it endure in the most important or significant rights cases? In many ways, the epistemological and somewhat legalistic justification of rights review suffers much the same problem as the notion of representative and deliberative parliamentarism. Both ideas are heavily stylised and vulnerable in practice - so-called ‘nirvana fallacies’.

In addition, an emphasis on the epistemological virtues of judicial review brings potential adverse consequences for rights practice. It encourages the conflation of judicial reasoning with the “real” meaning of rights. Such conflation might, of course, be instrumentally beneficial for compliance: it adds to the authority of judicial reason. Yet, it is also perilous. There is the danger of rigidity: the ideational or legal space for alternative moral and political conceptions of rights (whether more expansive, restrictive, or contemporary) is diminished. Further, it may encourage courts to be risk adverse. Judges may reason that restraint or refuge in doctrines such as justiciability is to be preferred to a charge of incompetence or illegitimacy. A legal and institutional environment open to the prospect of judicial infallibility may encourage both judicial dynamism, sensitivity, and innovation.

4 Functionalist Arguments

These lukewarm epistemological conclusions provide the appropriate departure point for a different set of arguments, which can be described as functionalist. By functional, I mean a goal-centred instrumentalism and not the empirical school of structural-functionalism. Framed by an institutional logic, functionalist claims begin in essence from the assumption that the judiciary is a political actor and that the legal process is a form of politics - not electoral politics but rather a distinct judicial politics. On its face, this observation does not challenge a positivist conception of adjudication, which accepts that law serves instrumental and political ends. However, we might acknowledge that law is inflected internally by a certain politics as judges use discretion to shape trial procedure, select and weigh facts, interpret and apply ambiguous language, and craft remedies.

In thinking about functional justifications, three arguments seem to motivate the choice of judicial review: (i) social stability; (ii) accountability; and (iii) structured public deliberation. Each will be discussed in turn. As will become clear, these choices are motivated by features that are clearly specific to judicial review of rights. I am less convinced by functionalist motivational claims for which there are clear alternatives to courts. The result is that the arguments draw on many of the specific features of the legal process identified above but strip away the pretension that law is fully insulated from politics as the epistemic dimension is given less weight.

The other consequence is that I do not consider some common functionalist arguments. This includes the claim that courts facilitate the adaption of constitutions to new social circumstances: the same role can be played by constitutional amendment. Likewise, I briefly consider but dismiss the inclusion of democracy amongst the motivations for judicial review. While tempting, such arguments are better trotted out in a more modest manner at the mitigatory level, in response to concerns that judicial review is anti-democratic. Nonetheless, the motivational arguments addressed herein possess shades of representative, participatory and deliberative democracy, to which I will allude. Moreover, there may be some specific national contexts in which the democratic function of judicial review is more salient.

4.1 Political legitimation and trust building

The first functional role of judicial review is the most ephemeral. Judicial review provides one answer to a foundational question in political theory and practice: how to justify the coercive power of the State or majoritarian-based government. By pointing to judicial review of basic rights, an assurance is offered to individuals who must comply with law or who may suffer its neglect. Authority is legitimated accordingly through the guarantee of certain procedural and substantive protections.

This reciprocal function of judicial review produces two instrumental benefits of normative significance. First, it may constitute a condition precedent for the initial formation of a “demos” or political community. Secondly, it may help build and maintain trust within society over time, particularly between distrustful factions, groups or classes. Social trust is increasingly recognised as crucial to achieving most ends in a modern State.

Curiously, this function of judicial review reverses an assumption that is thought to disqualify it, namely plurality of opinion. The very existence of disagreement between individuals and groups, together with uncertainty over the consequences of majoritarian rule, may precipitate the establishment of judicial review. As Rosenfield puts it: ‘in heterogeneous societies with various competing conceptions of the good, constitutional democracy and adherence to the rule of law may well be indispensable to achieving political cohesion with minimum oppression’.

The mechanism by which this occurs has been described as one of “insurance”. Empirically, we expect judicial review to emerge when individuals, groups and political parties feel compelled to protect themselves against future and unacceptable political risks. The result is a constitutional settlement that requires commitment to mechanisms in which all actors accommodate an acceptable, but not excessive, degree of risk. Such institutions transform ‘fuzzy uncertainty (where anything is possible)’ into a ‘specific assessable risk (of betrayal) that a trustor is prepared to accept’.

These risks may be apparent and visible at the time of constitution-making. For example, a losing side in an armed conflict, a small political party, or a linguistic minority, may all feel particularly vulnerable. In addition, judicial review of basic rights can provide an on-going means by which a State can legitimate its authority and sustain trust with different groups. Constitutional adoption does not imply constitutional acceptance: Violence, capital flight, migration, patronage and non-compliance with law (criminal, tax, labour, social security law conditions etc.) represent alternatives to submission to authority. Judicial review provides one means by which dissent is redirected back into political processes by helping ensure that the burdens of compliance are tolerable.

This function is not limited to the domestic level. International review represents a form of insurance. Notably, ratification of international human rights treaties and complaint protocols surges in periods of domestic constitutional reform. Morasvic argues that such actions exploit the ‘symbolic legitimacy of foreign pressure and international institutions to unleash domestic moral opprobrium’. As a result, the ‘domestic balance shifts in favour of protection of human rights’ as a State ‘seeks to avoid undermining its reputation and legitimacy at home or abroad’. Further, we might expect judicial review to expand at the international level in order to legitimate the growing coercive power of new global actors. For example, the adoption of the EU Fundamental Rights Charter was justified partly on the grounds that Europeans citizens should be protected from adverse decisions by the European Commission.

The political legitimation claim faces, however, four challenges. Each dampens the strength and breadth of the argument. First, there may be alternatives to constituting and sustaining trust. Judicial review is not the only means to enhance the sociological legitimacy of State authority. Other options may be available and function more efficiently or effectively: e.g., federalism, regional representation, representation quotas, reserved senate seats, affirmative action, advisory councils with veto powers (e.g. for indigenous groups), standing, or ad hoc commissions to investigate human rights abuses. Constitution-making should not be blind to these options.

However, the benefit of these alternatives is contingent. When a threat is less distinct and stable, and/or a group is geographically and politically dispersed, these approaches may be less relevant or feasible. There are likewise risks that specialist institutions will ossify over time or face political attack and de-funding. In these circumstances, judicial review may be a more practical and durable solution. It is diachronically flexible and more deeply institutionalised as a third branch of government. The judicial model may also be cheaper, in terms of financial costs as well as “agency costs” or “sovereignty costs”. The legal training of judges and their relative insulation from politics with a capital P may mean they evince sufficient fidelity to the legal text and the constitutional bargain.

Secondly, the shape of the insurance mechanism may be warped. Some scholars claim that the protection of minority elite interests is the dominant reason for the creation of judicial review. Hirschl contends that the ‘constitionalization of rights and the establishment of judicial review’ are ‘driven in many cases by attempts to maintain the social and political status quo and to block attempts to seriously challenge it through democratic politics’. By way of example, the leading Framers of the US Constitution were anxious to institutionalise multiple forms of control, including judicial review, to check parliamentary majorities and ‘popular irrational passions’ that would threaten property rights and encourage irresponsible fiscal policy.

These elitist claims are arguably overstated. Normatively, it is problematic to simply associate civil and political rights with elite privilege. For instance, there may be good reasons to enshrine the right to property, the most recognised right in the world, even if its application has not always been progressive. The right to property has been a condition precedent to the establishment or maintenance of mass and social democracy (locking in economic elites to the bargain) and an important protection for marginalised and indigenous groups, who sometimes face the gravest property rights violations.

Empirically, Hirschl’s assertion that elite interests dominate contemporary constitution making and treaty ratification is hard to square with all of the evidence. Constitutional settlement has often hinged on identity-based questions – e.g., linguistic, religious, or political rights for minorities – as well as socio-economic risks for particular groups. In Latin America, and elsewhere, the historical social policy failures of democracies and political clientilism generated stronger demands for social rights as a means of re-orienting politics. While in Sweden (1974) and South Africa (1994), socio-economic rights were introduced as a quid pro quo for recognising economic liberties.

Thirdly, to what extent will the insurance mechanism materialise in practice? Ginsburg deduces that is subject to the balance of power. The extent to which dominant parties will accept judicial review is dependent on the extent to which they must evince commitment in order to secure authority. If power is relatively diffused at the time of constitution-making, the insurance model will emerge in a strong form as all parties face future risks. If power is more concentrated, its emergence may be dependent on formal constraints: e.g., the securing of a supermajority to approve constitutional reform. In other words, ‘where constitutions are designed in conditions of political deadlock or diffused parties, we should expect strong, accessible judicial review’.

Morascvic makes an analogous though transposed argument at the international level. He argues that the emergence of strong judicial review is dependent on the distribution of new democracies, strong democracies, and dictatorships. The former will be strong supporters, seeking ‘to employ international commitments to consolidate democracy – “locking in” the domestic political status quo against their nondemocratic opponents’. However, in strong democracies, the benefits of such insurance weigh less with the result that the “sovereignty costs” of international review tip the balance towards an opposition. Strong democracies will be joined by more authoritarian States which seek to avoid significant challenge to the existing domestic order.

These rational choice theories provide an empirical check on the extent to which judicial review will emerge as an insurance mechanism, formally or substantively. However, there may be other causal pathways even when power is not spatially or diachronically diffuse. For instance, even if a dominant party is free from constitutional deadlock, it may face diffuseness and resistance elsewhere in society. Judicial review may be a means of establishing deeper consensus with all groups in society: a regime has to be legitimated in practice. At the international level, realist and constructive theories reveal how States may be respectively compelled or convinced of the need to establish judicial review; ranging from external foreign pressure or incentives to join trade regimes or the acculturation and ideational effects of the spread of rights and the rule of law.

Finally, there is the risk of insincere commitment, particularly if the motivation is elicited by once-off deadlock requirements or incentives or short-legitimacy gains. Authoritarian States may expand judicial power, adopt bills of rights or ratify international treaties simply to distract attention from its repressive apparatus. The State cloaks itself in the judicial robes of legitimacy. Even in strong democracies, this risk of a “false positive” exists: international judicial review may be supported simply ‘as an export-trade’. Many democratic governments supported the ECHR on the basis that it was ‘merely a Europeanization of their own national practices’ rather than the creation of a new domestic constraint.

However, even if judicial review helps shore up a despotic order, legitimises external relations, or permits national branding, these commitments may be nonetheless significant. They represent a Faustian bargain for any governing regime: citizens may feel empowered to turn to courts, which may be responsive in turn. The European Court of Human Rights is a striking example. For instance, the first cases challenging the criminalisation of sodomy were filed only two years after the convention came into force in 1953 – a claim that most States certainly did not expect at the time. Even in authoritarian States can this Faustian bargain transpire and impact social trust. Some independent surveys indicate rises in social trust after judicial reforms in China, even if the State’s motivations were partly suspect.

4.2 Accountability for commitments