Same, Same but Different: Proportionality Assessments and Equality Norms

Anna Nilsson

Postdoctoral Fellow in International Law, Faculty of Law, Lund University

Anna.Nilsson@jur.lu.sePublisert 17.12.2020, Oslo Law Review 2020/3, Årgang 7, side 126-144

Proportionality reasoning is an established form of legal argumentation under international human rights law, employed by the European Court of Human Rights and the United Nations (UN) human rights treaty bodies alike. However, relatively little has been written about its precise role and content in relation to equality norms. Proportionality scholars tend to draw on other examples to demonstrate how proportionality reasoning works in practice, and legal scholarship on equality and non-discrimination has not fully explored whether or how proportionality argumentation can assist us in distinguishing lawful state practices from unlawful ones. This article picks up these loose ends and develops a model of proportionality assessment tailored to the non-discrimination context. The model breaks down proportionality argumentation into a step-by-step process and sets out clear criteria to be fulfilled at each step. It illustrates the distinctive features of balancing as a part of discrimination analysis and provides useful guidance to national authorities tasked with such balancing. It is anchored in existing non-discrimination jurisprudence but structured so as to facilitate more predictable outcomes than existing justification tests.

Keywords

- proportionality

- equal treatment

- non-discrimination

- European Convention on Human Rights

- Robert Alexy

1. Introduction

The opening words of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – that ‘all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights’ – describe one of the fundamental ideals upon which human rights treaty law is based. Precisely what States must do in order to treat people as equals is, however, still a matter of contention. The European Court of Human Rights (the ECtHR or the Court) and other human rights monitoring bodies have developed their own tools for distinguishing legitimate practices from unlawful ones. Proportionality assessment is one such tool. Yet, relatively little attention has been paid to explicating its precise role and content in relation to equality norms. The Court’s proportionality assessments under Article 14 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (the ECHR or the Convention), the prohibition of discrimination, are often closely connected to the proportionality assessments it conducts in relation to the substantive right(s) at stake in a case. In many cases, the Court examines both whether there has been a violation of one or more substantive rights and whether there has been a violation of Article 14 in conjunction with any of these substantive rights. The arguments advanced in each of these analyses are often very similar, and their conclusions are the same. In some cases, the Court simply refers to the first proportionality assessment and holds that the reasons discussed there are ‘equally valid in the context of Article 14’. But if equality norms should play a role in human rights law, they must add something to the legal analysis.

In this paper, I pick up these loose ends. I discuss the use of proportionality reasoning as a tool for determining whether there has been a violation of Article 14 of the ECHR. I will argue that a well-structured proportionality assessment model, tailored to fit the non-discrimination context, can shed light on the specific harms caused by discrimination and can assist us in distinguishing lawful practices from unlawful ones in a more predictable manner. The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the normative content of Article 14 of the ECHR. I show that while the outcome of discrimination cases is often determined by a balancing test, the criteria that govern the outcome of this balancing remain vague. Section 3 explores whether Robert Alexy’s model of proportionality reasoning offers a way forwards, and here I argue that Alexy’s model clarifies some general aspects of the balancing process. However, a more detailed framework that incorporates the specific rules that inform legal argumentation under Article 14 could provide better guidance to decision-makers and thereby facilitate more predictable outcomes in discrimination cases. Section 4 develops such a framework, and section 5 discusses its merits. Section 6 contains some concluding remarks.

2. Discrimination and Justification

2.1 Introduction to Article 14

Article 14 of the ECHR states that ‘the enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in this Convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status’. It is clear from the treaty text and from the Court’s jurisprudence that Article 14 can only be invoked in connection with the other rights protected by the ECHR. A violation of Article 14 does not presuppose a breach of another right; it is sufficient that a practice interferes with an entitlement that falls within the ambit of a substantive right. Article 14 also provides an open-ended list of discrimination grounds or ‘statuses’. The Court has continued to add new statuses to the list, including, for example, age, sexual orientation, and disability. Some of these new statuses are quite different from the ones we typically associate with non-discrimination law: for instance ‘kind of prison sentence’, ‘place of residence’, and ‘former collaboration with secret services’. This has given rise to a controversy regarding whether Article 14 is primarily concerned with violations of the Aristotelian maxim that ‘like cases must be treated alike’ or whether its focus is on the social disadvantage experienced by certain groups (eg women, ethnic minorities, persons with disabilities, LGBTI individuals) irrespective of whether that disadvantage can be said to constitute differential treatment. As the following two sections illustrate, Article 14 prohibits both the differential treatment of people in similar situations and other practices that cause or reinforce social disadvantage. These sections also describe the basic rules for determining whether such practices can be justified.

2.2 Equal Treatment and Non-discrimination

The ECHR contains no definition of discrimination, but the ECtHR has developed a concept of discrimination in its jurisprudence. In short, the Court has established that, in order for an issue to arise under Article 14 of the ECHR, there must be a difference in the treatment of persons in analogous or relevantly similar situations on account of their sex, race, colour, or some other ‘status’. The claimant must show that he or she is in a situation that is analogous to that of others who are better off than the applicant. Two people or groups of people are, of course, never similarly situated simpliciter, but only similarly situated with respect to something. Thus, two persons can be similarly situated with regard to some domestic practices but not others. Citizens and migrants are, for example, similarly situated when it comes to the enjoyment of freedom of thought or the right to protection from racist attacks, but differently situated when it comes to the enjoyment of the right to vote in national elections or the right to benefit from certain welfare programmes.

In many cases, the Court does not discuss whether the claimant’s situation is in fact similar to that of others who are better off in relevant respects. Instead, such argumentation is postponed to the justification stage. This sequencing is typically to the advantage of the claimant because, once the relevant similarity has been established, the burden of argumentation and proof shifts to the State, which must justify its practices. From the Court’s perspective, combining the discussion of relevant similarity with the discussion of the justifiability of the practice makes perfect sense in cases where the key problem with the practice under review is that the justification for it is weak. In such cases, the contextual reasoning necessary to establish whether two persons or groups are similarly situated with regard to a certain social good is very similar to the reasoning necessary to establish whether differential treatment is justified. This does not mean, however, that claimants can dispense with comparative argumentation altogether. The Court has rejected a significant number of discrimination claims on the basis that the claimant failed to demonstrate that he or she was situated in a similar way to others who enjoyed a protected freedom or social benefit that the claimant could not enjoy.

Article 14 has been interpreted so as to cover both so-called direct discrimination (ie differential treatment based on a prohibited status) and indirect discrimination (ie disadvantageous treatment of protected groups resulting from the application of a general policy or measure that is couched in neutral terms). Violations of these prohibitions can arise out of actions as well as out of failures to act. Article 14 includes not only an obligation to refrain from adopting and implementing discriminatory laws and policies but also a number of positive obligations to mitigate the harmful consequences of past discrimination and to combat the discriminatory actions of private parties. In Horváth and Kiss v Hungary, for example, the Court held that States have ‘specific positive obligations to avoid the perpetuation of past discrimination’, including an obligation to ‘undo a history of racial segregation in special schools’. The Court has also declared that States have a duty to investigate, prosecute, and punish racist, homophobic, and religiously motivated violent acts committed by private individuals. The same obligation exists with regard to domestic violence, which disproportionately affects women. In relation to persons with disabilities, States must take reasonable action to remove the legal, physical, and other barriers that circumscribe the opportunities of such persons to enjoy their rights and freedoms on an equal basis with others. As this brief description of Article 14 illustrates, a wide range of state policies and practices may fall within the scope of this provision. Some of these practices serve legitimate aims and can be justified, as the next section explains.

2.3 Justified Practices

The ECtHR has on numerous occasions declared that not all disadvantageous treatment that is directly or indirectly linked to a discrimination ground violates the ECHR. Policies and practices can be justified if they serve a ‘legitimate aim’ and if there is a ‘reasonable relationship of proportionality’ between the means employed and the aim to be achieved. Starting with the first criterion, aims are legitimate if they are recognised as such in the ECHR treaty text or are otherwise compatible with the treaty. This criterion serves to weed out policies with offensive aims (eg sexist, racist, or homophobic aims), but little else. In most cases, States claim that their policies serve respectable aims, and the ECtHR typically makes little effort to challenge such claims. In addition to the legitimate aims enumerated in Articles 8–11 of the ECHR, the Court has, for example, accepted public tranquillity, the protection of ‘the family in the traditional sense’, and ‘allocating a scarce resource fairly between different categories of claimants’ as legitimate aims within the context of non-discrimination.

The other part of the justification test includes a proportionality assessment. The policy under review must strike a fair balance between the protection of individual rights and freedoms and the collective interests of the community. When assessing whether a fair balance has indeed been struck, a number of factors are taken into account, including the effects of the policy under review, the existence of alternative ways of achieving the policy’s aims, the basis for differentiation, and the social situations of those affected by the policy. Consideration is also given to whether the policy concerns a politically sensitive issue and whether there is a European consensus on what Article 14 requires in the circumstances at hand.

When it comes to the effects of the practice under review, the general idea is that it takes more to justify policies or practices that severely restrict the enjoyment of rights than it does practices with less severe consequences. Precisely how we ought to determine ‘how much’ a policy interferes with a specific right is seldom discussed in general terms, although some patterns can be inferred from the jurisprudence. Rigid or indiscriminate policies are often held to be more restrictive than policies that allow for exceptions. Similarly, a policy that applies for a short period of time is often seen as less restrictive than a more permanent policy.

When discussing the effects of domestic practices, the Court also pays attention to alternative ways of achieving what the State is seeking to achieve. If there are ways of achieving the same aim that imply fewer restrictions on human rights and freedoms, then this speaks in favour of finding the policy under review disproportionate (this is sometimes referred to as the ‘least restrictive means’ rule). This has led the ECtHR to reject policies that are too far reaching. In Sidabras and Džiautas, for example, the Court rejected a policy that prevented former KGB agents from working not only within the public sector but also in a number of areas in the private sector for a period of ten years. The policy had come into force nearly a decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Although the Court recognised the need to prevent persons who had served oppressive regimes in the past from taking up certain public positions, it did not see that this implied barring such persons from positions in the private sector as well.

The ECtHR has drawn on the American ‘suspect classifications’ doctrine as a way of signalling that certain forms of discrimination are more difficult to justify than others. According to this doctrine, differential treatment based on certain grounds, including gender/sex, ethnic origin/race, sexual orientation, and disability, is seen as inherently suspect and so as implying the need for a particularly persuasive justification if it is to be deemed lawful. According to the Court, it takes ‘very weighty reasons’ to justify differential treatment based on these grounds. Of course, negative attitudes towards certain groups or patriarchal ideas about the subordinate position of women can never justify the disadvantageous treatment of these groups. Nor is it sufficient that such differential treatment contributes to the aim in question. Rather, States must demonstrate that the differential treatment is necessary in order to achieve the aim of the policy. The Court’s reasoning in Konstantin Markin is illustrative in this respect. The issue in the case was whether military servicemen could be refused parental leave when such leave was available to servicewomen. The stated aim of the policy was to secure the operational effectiveness of the armed forces. Whilst the Court recognised that it may be justifiable to deny certain categories of military personnel – male or female – parental leave on the grounds of their strategic position, their possession of rare technical qualifications, or their active involvement in military action, it maintained that a policy that denies servicemen parental leave on the basis of their sex violates Article 14 in combination with Article 8. There are, however, situations in which differentiation based on a suspect ground has been accepted as lawful. For example, the Court still accepts as lawful domestic policies preventing same-sex couples from marrying and different-sex couples from registering their partnerships. It also accepts as lawful policies that exempt women (but not men) from the possibility of being sentenced to life imprisonment.

The Court has increasingly been paying attention to the situation of those affected by the policy in question. Some groups have been identified by the Court as particularly vulnerable and thus in need of extra protection or care from the government. These groups include Roma, persons with psychosocial disabilities, persons living with HIV, asylum seekers, persons belonging to the LGBTI community, victims of domestic violence, and women of colour working in the sex industry. According to the Court, it takes very weighty reasons to justify restrictions on the fundamental rights of such groups. States must be particularly careful about ensuring that their policies and practices are not based on stereotypical beliefs about the characteristics or behaviours of members of these groups, as this could perpetuate public prejudice and exacerbate social exclusion.

Last but not least, the ECtHR has established that States enjoy a certain amount of discretion (a margin of appreciation) when balancing the reasons for and against their policies in particular cases. Because of their direct knowledge of local circumstances, traditions, and legal cultures, national authorities are ‘better placed’ than international courts to appreciate the values at stake and how they ought to be balanced in concrete cases. The Court is particularly inclined to accept domestic regulations in policy areas that involve the balancing of politically sensitive interests, such as welfare policy or national security. Another factor that affects the degree of deference given to States is the presence or absence of a consensus among States Parties to the ECHR about what Article 14 requires in the situation under review. In situations where there is such a consensus, a policy that departs from this consensus is likely to be taken to violate the ECHR, although compelling reasons anchored in the specific political, historical, and legal context of the country in question may justify a departure from the common European approach to a specific issue. With regard to issues on which there is no consensus, States have more room for manoeuvre. Indeed, the lack of consensus is an important reason why the Court still accepts domestic bans on same-sex marriage and regulations that ban the wearing of certain religious garments in public places. The Court has not only used the existence or absence of a consensus on a certain issue in order to determine the degree to which it should defer to States when balancing equality interests with other domestic constitutional values and policy choices; it has also referred to such considerations in order to justify changes to its views about what Article 14 permits and prohibits. Changed attitudes towards parental leave and transsexuality, for example, have led the Court to change its position on fathers’ rights to parental leave and the legal recognition of the gender of post-operative transsexuals.

In sum, Article 14 prohibits both direct and indirect discrimination. Prima facie discrimination may be justified if the State practice in question serves a legitimate aim and is proportionate in relation to that aim. A plurality of factors is taken into account in determining whether a practice is proportionate, including the basis for differentiation, the aim and effects of the practice, alternative ways of achieving the practice’s aim, the social situation of those affected, and whether the practice concurs or conflicts with the European consensus on the issue (if there is one). However, it remains unclear how precisely these factors are supposed to relate to each other and influence the outcome of the balancing exercise implicit in the Court’s justification test. The Court’s reasoning on differential treatment based on ‘suspect’ grounds and its position on members of vulnerable groups imply that especially strong arguments are necessary to justify prima facie discrimination that is based on certain grounds or that affects persons that have suffered considerable discrimination in the past that has had lasting consequences. Likewise, the existence or absence of a European consensus on an issue affects the standard that must be met in discrimination cases. Still, these guidelines raise further questions that lack clear answers. One such question is whether ‘nationality’ (or ‘religion’) is a suspect ground and, if so, what this implies for the ability of States to restrict the access to certain rights and benefits to its own citizens. In addition, it remains unclear how we ought to identify vulnerable groups, and this lack of clarity undercuts the usefulness of this doctrine. And the Court’s application of the consensus rule raises questions about what qualifies as such a consensus. How similar must the relevant domestic interpretations of what the ECHR requires be, and how many States need to agree? Moreover, these guidelines leave open the question of how to approach the not uncommon situation in which these different rules point to different conclusions, such as in cases involving discrimination based on suspect grounds in politically sensitive policy areas. The next section explores whether Robert Alexy’s model of proportionality reasoning might provide a more structured approach to proportionality assessments in general and balancing in particular.

3. Alexy’s Proportionality Assessment Model

Robert Alexy’s model of proportionality argumentation is part of a theory of constitutional rights that he lays out in Theorie der Grundrechte (A Theory of Constitutional Rights). It is developed as a reconstruction and theorisation of the jurisprudence of the German Constitutional Court. The high level of abstraction of his model, however, allows for it to be more widely applied. Indeed, Alexy’s rules for proportionality argumentation have inspired human rights courts around the world, including the Strasbourg Court. As we shall see, there are significant overlaps between the rules that inform proportionality argumentation in the Court’s jurisprudence and the rules deployed in Alexy’s model. This section provides a description of the basic rules that make up Alexy’s model of proportionality argumentation and the balancing process.

Alexy divides proportionality assessments into four stages, with a standard to be met at each stage. These stages concern the legitimacy of the aim(s) of the practice, the practice’s suitability, the practice’s necessity, and the practice’s proportionality in the narrow sense. In Alexy’s model, then, the first question to be asked is whether the policy or practice under scrutiny has a legitimate aim. Any aim that does not conflict with the aims, objectives, and provisions of the relevant legal framework is legitimate. This corresponds to the standard applied by the European Court in its discrimination jurisprudence. The next stage, the suitability stage, asks an empirical question: does the policy or practice under review contribute to its aim(s)? Only means that in fact contribute to their aims are acceptable. This criterion also figures in the Court’s case law. The ineffectiveness of a State policy constitutes a strong argument against its lawfulness.

The third stage of Alexy’s model, the necessity stage, incorporates a requirement that the State must use the means that will, ceteris paribus, be the least restrictive in achieving the aim in question. If a legitimate aim can be achieved by two or more equally effective (or suitable) means, then the policy or practice that interferes the least with rights norms must be chosen. This rule is certainly consistent with the Court’s argumentation in many, albeit not all, discrimination cases.

The last stage of Alexy’s proportionality model involves a balancing exercise that aims to ensure that the legally relevant reasons in favour of the policy or practices under scrutiny are, broadly speaking, ‘on balance with’ the reasons against it. This exercise can be broken down into three steps. The first step involves estimating the degree to which a policy interferes with a right protected under constitutional law (here the ECHR), eg freedom from discrimination, in the circumstances in question. Thereafter, a similar estimation is made with regard to the competing right or public interest, eg protection of the democratic process, by looking at the degree to which a prohibition of the policy would interfere with this right or interest it aims to protect. Lastly, the two estimates are compared. If prohibiting the policy would interfere more with the competing right or interest (eg protection of the democratic process) than permitting the policy would interfere with the relevant constitutional right (eg freedom from discrimination), then the policy is justified. If the degrees of interference are equal, then the decision-maker has discretion about whether to implement the policy.

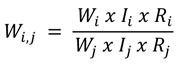

These steps are captured in Alexy’s weight formula, which also illustrates the form of argument that balancing represents. In its simplest form, the formula reads:

Alexy’s proportionality assessment model does not tell us exactly how to arrive at an estimate of the weight of an interference with a right or interest. Such estimates ought to be made in accordance with the general rules of legal argumentation. Take restrictions on voting rights for persons under guardianship as an example. Most human rights lawyers would be able to list a number of factors that would have to be considered in order to determine ‘how much’ such restrictions interfere with the right to vote or the right to vote in combination with Article 14 – ie to determine the weight of Ii. It would be relevant to consider whether the restriction is absolute or admits exceptions. A policy that allows persons under guardianship to regain their right to vote after having demonstrated that they possess the relevant capacity to make an informed voting decision interferes less with the right to vote than a policy that does not allow for such an exception. The proportion of the voting-age population affected by the policy may also give us an indication of the magnitude of the harm brought about by it. In Alajos Kiss v Hungary, which concerned the denial of the right to vote to persons under guardianship, the Court noted that the policy in question affected a significant share of the voting-age population – about 0.75 per cent. The fact that the policy targeted an already marginalised group with limited political power, ie persons with intellectual or psychosocial disabilities, was another aggravating factor. Last but not least, those engaged in the balancing exercise must consider whether the policy in question adheres to or conflicts with any established European consensus on the matter.

According to Alexy’s model, in order to determine ‘how much’ the rejection of this policy would interfere with the right or public interest it aims to protect (Ij), one has to consider the negative implications of replacing that policy with one that interferes less with the right(s) at stake. To return to the example of the disenfranchisement of persons under guardianship, a less restrictive alternative might be a policy that applies only to those who fail to demonstrate that they possess the capacities relevant to voting, or one that also ensures that such persons have access to support to enable as many as possible to make judicious voting choices. It could also, of course, be a policy which simply grants persons under guardianship the same voting rights as others. The negative implications of the two first alternative policies would mainly concern the extra public resources that would be necessary to implement them. A system that was based on assessments of individuals’ fitness to vote or that provided decision-making support to individuals would require more public resources than a system that simply disenfranchised certain categories of the population, and a State’s capacity to bear such costs will, of course, depend on the financial situation in that particular country. The costs of granting persons under guardianship the same right to vote as others is of a different nature, and concerns the risk that the outcome of elections will be affected by the injudicious choices of these individuals. Needless to say, it is difficult to assess the normative ‘weight’ of these costs. The weight formula, however, shows that the more restrictive and harmful a policy is, the stronger the reasons that speak in its favour must be.

Alexy introduces two other sets of variables into the formula in order to accommodate the fact that the rights and public interests at stake might differ in their legal importance and in order to ensure that decision-makers pay attention to the (epistemic) reliability of the assumptions upon which their legal argumentation rests. The extended weight formula reads:

Wi and Wj refer to the weights of the competing rights or public interests relative to each other according to the constitution (here the ECHR) but independently of their weight or importance in the case at hand. These variables are often called the ‘abstract weights’ of the rights or interests. In the example of the disenfranchisement of persons under guardianship, Wi refers to the importance the ECHR attaches to the equal enjoyment of the right to vote, while Wj reflects the importance it attaches to the interest of ensuring that the results of elections reflect the considered choices of those eligible to vote. Ri and Rj represent the extent to which the assumptions upon which the estimates about the abstract weights (Wi and Wj) and degrees of interferences (Ii and Ij) rest are reliable. Alexy’s model requires decision-makers to make assumptions about the effectiveness of policies and the effectiveness of their alternatives. But our knowledge about how effectively a particular policy or practice contributes to the achievement of a given aim is often uncertain or contested. This means that policy-makers have to make decisions based on uncertain information. Alexy’s formula tells us that we must take such (epistemic) uncertainty into account when balancing. This requirement too finds support in the Court’s jurisprudence. A lack of reliable evidence for governments’ arguments in favour of policies under review or for their claims about the harms that would follow if certain policies were prohibited has led the Court to dismiss or attach little weight to such argumentation.

This brief overview of Alexy’s proportionality assessment model sheds light on the structure of proportionality argumentation and balancing as a form of legal argumentation. Alexy’s proportionality model does not, however, assist us in determining the abstract weights of the rights and interests at stake in a given case or the degree to which a certain policy contributes to or interferes with these rights and interests. Such determinations must be made in accordance with the rules of legal argumentation. In relation to Article 14, these include the rules and doctrines developed by the Court in its jurisprudence, as discussed in section 2. In the next section, I will discuss how and to what extent these rules and doctrines can be incorporated within Alexy’s framework.

4. Tailoring Proportionality Assessments to the Non-Discrimination Context

4.1 Introduction

As I mentioned above, Article 14 has been interpreted as expressing both the idea that, when it comes to the enjoyment of human rights, like cases must be treated alike and the idea that practices that cause or reinforce social disadvantage are unjust and must be opposed. The first idea implies that Article 14 forbids arbitrary restrictions on rights and social goods on the basis of grounds linked to a protected status, interpreted in a broad sense. The second idea is less interested in whether the policy or practice constitutes same or differential treatment of similarly situated groups and more focused on the policy’s harmful effects on certain groups. That does not mean that the question of whether the policy makes arbitrary distinctions between persons in analogous situations is irrelevant; it just means that the absence of such arbitrariness is not sufficient to justify prima facie discrimination with particularly harmful effects. The following two sections discuss how these two ideas can be incorporated into the proportionality assessment, and into the balancing process in particular.

4.2 Incorporating the Idea of Treating Likes Alike into Proportionality Assessments

To incorporate the idea that like cases be treated alike into proportionality argumentation, the framework developed in this article adds two rules to Alexy’s model for proportionality assessments described in section 3. The first rule can be viewed as a specification of Alexy’s suitability criterion (ie State policies that interfere with human rights must contribute to their aims) tailored to the discrimination context. To be justified under Article 14, it is not sufficient for States to demonstrate that their policies contribute to their stated aims. If the policy constitutes direct discrimination, then the State Party must demonstrate that differential treatment on the basis of a protected ground serves the aim in question. This rule is omnipresent in the Court’s jurisprudence under Article 14, and it explains why the Court has found that there were violations of this provision in a number of cases involving so-called suspect as well as non-suspect grounds. States may, for example, restrict maternity leave to women, but they may not restrict parental leave to women. Maternity leave aims to enable mothers to recover from childbirth and to breastfeed their babies if they so wish, whilst parental leave aims to enable a parent, ie the mother or the father, to stay at home and care for the child. A failure to meet this criterion arguably constitutes a sufficient reason to conclude that there has been a violation of Article 14. To hold otherwise would be tantamount to saying that differential treatment based on sex (or any other protected ground) may be justified even though such differentiation is irrelevant in achieving the aim and even though the policy makes no contribution to its purported aim.

In relation to indirect discrimination, a similar requirement could be formulated in order to oblige States to justify the disparate impact a particular policy has on a protected group. For example, if States decide to set up special classes to help pupils improve their command of the language of instruction, it is only to be expected that immigrant children and children from linguistic minorities will be overrepresented in such classes. It would be much harder, if not impossible, to explain, for example, an overrepresentation of pupils in wheelchairs, or, as in the case DH and Others v the Czech Republic, to explain why Roma children are overrepresented in special schools for children with intellectual disabilities. We have no reason to believe that such disabilities are more common within the Roma population; rather, such a disparate impact suggests underlying bias and racism in the domestic system.

The second rule belongs to the balancing stage and seeks to ensure that the arguments put forward in defence of a particular policy must be internally consistent. A policy may seem proportionate when viewed in isolation but still be unjust when seen in context. It may, for example, seem reasonable to restrict the right to vote in national elections to citizens who are able to make judicious voting decisions. The great value we attach to the democratic process and the need to protect the integrity of the electoral system could undergird such a claim. It is, however, also possible to argue that the right to vote is not dependent on the possession of cognitive skills such as the ability to critically assess political information. Voting is a subjective choice, linked to personal preferences, and it is not for the State to determine what constitutes a valid political opinion or which capacities are necessary to formulate such an opinion. Even if both positions on the right to vote were legally tenable, which would imply that States had discretion on this matter, it seems wrong to accept that restrictions on voting rights for citizens with psychosocial disabilities could be justified on the basis of the first claim and, at the same time, to accept that the tolerance of uninformed voting by citizens without such disabilities could be justified on the basis of the second. Presumably, Article 14 requires that the reasons put forward to justify restrictions of rights apply to everyone.

This second rule differs from the first rule discussed above, which requires States to explain the rationale behind policies that stipulate differential treatment based on protected grounds or that have disparate impacts on protected groups. The problem with a policy that justifies restrictions on voting rights for persons with psychosocial disabilities in an inconsistent way is not that the State is acting on the basis of false or unsubstantiated beliefs about persons with psychosocial disabilities. A lack of certain cognitive skills certainly is more prevalent among members of this group than it is among persons without such disabilities. The problem, from the equal treatment perspective under discussion here, is that a policy that deprives persons with psychosocial disabilities of the right to vote is vastly overinclusive (many persons with psychosocial conditions are indeed able to make informed voting decisions) and that it holds them to a higher standard than many other groups. People with psychosocial disabilities are not the only ones whose ability to make judicious political choices might be questioned. A range of factors may impact our ability to make such choices, including whether we have consumed alcohol or drugs, whether we are very young (or, indeed, very old), or whether we are simply uninterested in politics. Whilst we accept age limits on voting, which can be justified by the fact that most children will eventually reach an age at which they will be allowed to vote, it would be unthinkable in most European democracies to require adult citizens without cognitive disabilities to demonstrate their knowledge of the political system to be able to cast a vote. An internally consistent defence of a policy that required members of certain groups to pass a test before they could vote would have to engage with these questions and provide some other explanation of why it is reasonable to restrict voting rights for some citizens and not others.

4.3 The Harms of Unequal Treatment and Discrimination

Equality scholars describe the harms caused by discrimination in different ways, and, as several authors have noted, consensus on what these harms are remains elusive. Having said that, a number of harms are typically highlighted by the ECtHR and equality scholars alike. These include personal (emotional) harms and well as group-related ones. Starting with personal harms, empirical studies suggest that discriminatory practices have negative effects on the mental well-being of their victims. Persons who experience frequent exposure to discrimination and similar forms of unfair treatment report psychological distress, unhappiness, and depression. The ECtHR has recognised such harmful effects of discriminatory practices. In DH and Others v the Czech Republic, for example, the Court held that the pupils placed in special schools for children with intellectual disabilities should be compensated for the anxiety, frustration, and humiliation they had suffered as a result of that policy.

The group-related harms of unequal treatment and discrimination take a variety of forms and have been conceptualised in numerous ways. Denise Réaume and Deborah Hellman claim that what is harmful about discrimination is that it is an affront to human dignity: discrimination conveys a demeaning message that some are of lesser worth than others. Charilaos Nikolaidis argues that social oppression, in the form of stereotyping and stigmatisation, distinguishes violations of Article 14 from other human rights violations. Other authors have described the harms of discrimination in terms of uneven or unfair distribution of material resources, political power, and opportunities to pursue one’s life projects and similar social ‘goods’. In the recent literature, pluralistic accounts have recognised that different forms of discrimination cause different harms and combinations of harms.

The Court has not engaged in a principled discussion about the specific harm(s) brought about by domestic practices that violate Article 14 but has approached such questions on a case-by-case basis. Racial and homophobic violence, for example, have been said to disrespect human dignity. The harm brought about by the segregated education of Roma children was, by contrast, described not as a violation of human dignity but primarily in terms of substandard education, which, in turn, was described as limiting the children’s future career opportunities and their capacity to participate actively in mainstream society. The harm caused by stereotyping has primarily been discussed in relation to policies that reinforce stereotypical ideas about men and women and about vulnerable groups. In Konstantin Markin, for example, the Court held that policies that reinforce the stereotype of the male breadwinner and the female homemaker are harmful to women’s careers as well as to men’s family lives. In most cases, however, the Court’s discussion of the harm caused by a policy focuses on whether the claimant has been placed in a position of comparative disadvantage, that is, whether he or she cannot enjoy a right, or an aspect of a right, set out in the Convention to the same extent that others can.

The harms of discrimination and unequal treatment not only take various forms but also differ in the impact they have on people’s lives. Some discriminatory practices have profound consequences. The far-reaching and long-lasting effects of segregated education have already been mentioned. Systems of plenary guardianship not only prevent certain persons with intellectual and psychosocial disabilities from voting, and thereby ensure that their interests remain low on the political agenda, but also deprive them of the opportunity to make almost every important decision in life, including decisions about where and how to live. The failures to address gender-based, racist, homophobic, and similar forms of violence are other examples of discrimination with particularly severe implications. Some other practices that fall within the ambit of Article 14 are clearly unlawful but have a more modest impact on people’s lives. Examples of such practices would be laws that prevent married couples from using the wife’s (rather than the husband’s) surname as the family name, or laws that mean that the burden of jury service is borne disproportionately by men. This is not to trivialise the injustice of such discriminatory practices or to deny their role in sustaining the unequal power relationship undergirding more brutal forms of discrimination, such as gender-based violence. It is, however, to recognise the possibility of moral and legal differentiation. Alexy’s balancing model asks us to assess ‘how much’ a particular policy or practice interferes with the right(s) at stake (here Article 14). The magnitude of the harm brought about by the policy in question is a key factor in such an assessment, and it thereby affects how strong or weighty the reasons must be in order to justify the policy in the circumstances at hand.

The magnitude of the harm caused by a particular policy also depends on the situation of those affected by it. Discriminatory policies affecting already marginalised groups, and thereby compounding the hardship experienced by members of these groups, arguably generate more harm than policies which affect more privileged groups. This may explain the Court’s position that it takes particularly weighty reasons to justify prima facie discrimination against vulnerable groups and that States must avoid perpetuating stereotypical beliefs about members of these groups. Another reason to view policies that reinforce negative stereotypes as particularly harmful is that stereotypes affect all of us and serve to maintain existing power relationships between privileged and marginalised groups, which makes it more difficult to create equal and inclusive societies.

4.4 A Framework for Proportionality Argumentation within Discrimination Analysis

This section summarises the discussion in the preceding two sections in order to outline a framework for evaluating justifications of prima facie discrimination under Article 14 of the ECHR. The evaluation commences with an assessment of the legitimacy of the policy’s aim(s) and the means–ends rationality of the policy. This initial examination can be viewed as a simple way of rejecting at the outset policies and practices that are clearly unjustified. The following criteria must be met:

-

The policy must be motivated by a legitimate aim or legitimate aims.

-

The policy must contribute to its legitimate aim(s). If the policy constitutes direct discrimination, then the State Party must demonstrate the relevance of differentiation based on a protected status. If the policy constitutes indirect discrimination, then the State Party must provide sound reasons for the disparate impact on protected groups; the disparate impact must not be the result of the biased behaviour of public officials.

-

The policy must not go beyond what is necessary to achieve its aim(s).

As discussed above, legitimate aims are aims that are compatible with the ECHR. This weeds out policies with particularly offensive aims, such as racial segregation, but this criterion is a low threshold. The second criterion ensures that policies do not make distinctions between groups for irrelevant reasons. The third criterion prohibits policies that are more restrictive than is necessary to contribute to their aims.

To determine whether a particular regime is proportionate (in the narrow sense), the reasons speaking in favour of its compliance with the ECHR must be weighed against the reasons speaking against its compliance. To count as lawful, the following criteria must be met:

-

The reasons in favour of a policy must have equal or greater weight than the reasons against the same policy. The reasons against a policy include arguments about ‘how much’ that policy disrespects human dignity, causes or upholds comparative social disadvantage, and contributes to public prejudice in the circumstances at hand.

-

Argumentation about the weights of the reasons for and against the policy must be internally consistent.

These criteria describe a balancing process that is specifically tailored to the discrimination context. As outlined in section 3, balancing is a form of legal argumentation that obliges decision-makers to take all legally relevant considerations into account. These include arguments about the scope and content of the legal norms at stake, about the ‘costs’ of accepting or rejecting the domestic practice under review, and about the reliability of the assumptions upon which these arguments are based. As I have explained, the harms of unequal treatment and discrimination include both personal and group-related harms, and some practices are worse than others because of the magnitude of the harm they cause. This explains why it takes weightier reasons to justify such practices. To determine the weight of the reasons in favour of a policy, we must consider the costs of amending it in such a way as to produce less harm. Needless to say, it is difficult to determine such weights, and there will often be disagreement about them. Such disagreement is clear from the different ways that States Parties to the ECHR approach certain matters (eg same-sex marriage) and from the many dissenting opinions accompanying the Court’s judgments in discrimination cases. Few, however, would contest that it makes legal sense to say that some policy changes interfere more with States’ legitimate interests than others. The costs of modifying policies that fail to meet the second criterion outlined above, and therefore do not contribute to their aims, are certainly minimal. The costs of accepting different expressions of human diversity (eg the wearing of the hijab in public places) are arguably also low, unless they interfere with the rights of others. Transforming our societies into inclusive ones where everyone has a genuinely equal opportunity to participate in public affairs and benefit from education, welfare programmes, and other social goods is, on the other hand, a project with more far-reaching implications for State budgets and domestic legislators’ room for political manoeuvre. These implications may nevertheless be ‘outweighed’ by the devastating consequences of social exclusion and of the failure to accommodate the needs of marginalised groups, as in the case of the segregated education of Roma children.

The fifth criterion serves to ensure that any justification of unequal treatment is internally coherent. The content of this criterion has been discussed in section 4.2, and I will not repeat this discussion here.

5. The Value of Structured Proportionality Assessments Tailored to the Non-discrimination Context

The sort of structured proportionality analysis described in section 4.4 breaks down proportionality argumentation into a step-by-step process and sets out clear criteria to be fulfilled at each step. Policies and practices that fail to meet one of these criteria are rejected at that stage, without the analysis having to proceed to the remaining criteria. The cases concerning the segregated education of Roma children could, for example, have been decided on the basis of their utter ineffectiveness in achieving their stated aim of responding to the specific educational needs of this group of children. Similarly, simply considering the necessity (in the Alexian sense) of policies could have enabled the Court to reject certain domestic policies in several cases without having had to enter into a balancing process. In Konstantin Markin v Russia, for example, it is clear that the policy, which barred servicemen but not servicewomen from receiving parental leave on the basis that this was necessary in order to safeguard the operational effectiveness of the armed forces, was unnecessarily restrictive, because the same aim could have been achieved by a gender-neutral policy. A neutral policy would not reinforce harmful gender stereotypes and would therefore interfere less with Article 14. The very fact that other contracting States have adopted a gender-neutral approach to military personnel’s rights to parental leave provides support for this argument. Once this conclusion had been reached, there would have been no need to discuss the rigidity of the legal provisions or the scope of the margin of appreciation. The fact that the policy failed to meet the necessity criterion would have been sufficient to reject it as a violation of Article 14 under the framework set out in section 4.

The framework incorporates the basic rules that inform the Court’s jurisprudence, but it does not require decision-makers to determine whether the policy under consideration is one which differentiates on a suspect ground. The criteria discussed in section 4.2 are arguably equally relevant to all disadvantageous treatment on protected grounds, and the additional harm typically brought about by policies that differentiate on the basis of suspect grounds, eg the reinforcement of negative stereotypes, is taken into account at the balancing stage. At the balancing stage, the reasons for and against a particular policy is weighted against each other, and the harm of negative stereotyping implies that particularly weighty reasons will be required if such policies are to be considered acceptable. An advantage of this approach is that it allows us to avoid having to discuss whether a certain basis for differentiation, such as nationality, religion, or age, is ‘suspect’ or not and focuses the discussion on the policy’s rationale and its harmful effects in a specific context. There are plenty of perfectly legitimate distinctions between persons of different ages or between citizens and non-citizens, but there are also problematic ones. Elderly persons residing in care homes and migrants, not least unaccompanied migrant children, are among the most vulnerable groups in Europe today. The fact of the vulnerability of these and other groups ought to affect discrimination analysis regardless of whether ‘nationality’ and ‘age’ are deemed ‘suspect’ classifications.

Finally, the framework clarifies the proper scope of state discretion. In all situations in which the reasons for and against a policy are of equal weight, States may either maintain their policy or abandon it. This room for political manoeuvre does not hinge on the absence of a European consensus about how best to resolve a certain conflict of rights and interests or about what Article 14 requires of States in such situations. Rather, it depends on an evaluation of the legal weight of the arguments behind such interpretations of Article 14. That does not mean that information about how States approach equality matters and how they interpret their obligations under Article 14 must be ignored. Proportionality assessments, and balancing in particular, involve the difficult process of producing estimates of the merits of a particular policy and of alternative ways of achieving the policy’s aims. Information about the alternatives actually adopted by other States, and their experiences of the advantages and disadvantages of these alternatives, can provide valuable input here. In addition, the Court’s consensus rule can serve as a useful device, providing decision-makers with a hint as to the reasonableness of the policy under consideration. The absence of a common approach indicates that there is disagreement about how best to approach an equality matter. Such disagreement may, of course, be the result of legitimate exercises of political choice in situations in which States have discretion because the reasons for and against a number of approaches are of equal weight. Differences in approach may also be explained by domestic factors that affect the strength of the arguments for and against a policy in different ways in different countries. The harm caused by a policy that, for example, prevents the wearing of the hijab in public places will depend on the social position of Muslim women, which will differ from State to State. Under the framework set out here, the mere absence of a common European position on a matter cannot, however, be a sufficient reason by itself to accept a policy as justified.

6. Concluding remarks

A problem with the justification tests developed by the ECtHR is that the criteria used to determine their outcomes are unclear. Because Article 14 is not undergirded by a general theory of non-discrimination, it is unsurprising that the Court has hesitated to explain the precise weight given to the different reasons in play in balancing and the criteria governing the outcome of the balancing process. This lack of explanation, however, makes the Court’s proportionality assessments less predictable than they might otherwise be, and it leaves States without clear guidelines about what Article 14 requires of them. After all, it is the State that has the primary responsibility to promote equality and prevent discrimination at the domestic level. To be effective in discharging this responsibility, States need to know what their duties are. In this article, I have demonstrated that a more structured approach to proportionality assessment under Article 14 is possible and reconcilable with the basic rules that inform the ECtHR’s jurisprudence. The framework set out in section 4 could provide useful guidance to national authorities tasked with such balancing and could assist the Court in its reviews of domestic policies and practices. It is hence not only of theoretical interest but also of practical utility.

- 1GA Resolution 217A (III), 10 December 1948, UN Doc A/810, Arts 1, 2(1), and 7.

- 2Oddný Mjöll Arnardóttir, ‘The Differences That Make a Difference: Recent Developments on the Discrimination Grounds and the Margin of Appreciation under Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights’ (2014) 14(4) Human Rights Law Review 647, 663 <https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngu025> and Tarunabh Khatian, A Theory of Discrimination Law (Oxford University Press 2015) 8.

- 3Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, 4 November 1950, ETS 5.

- 4Eg SAS v France [GC], no 43835/11, §§ 160–62, ECHR 2014 (extracts); Leyla Şahin v Turkey [GC], no 44774/98, §§ 163–66, ECHR 2005-XI; and Sheffield and Horsham v the United Kingdom, 30 July 1998, § 76, Reports of Judgments and Decisions 1998-V. In these cases, the ECtHR starts with an examination of the substantive provisions at stake. In other cases, the Court has started with the discrimination analysis and then proceeded to discuss whether there has been a violation of the substantive provision alone. See eg Belli and Arquier-Martinez v Switzerland, no 65550/13, §§ 122–24, 11 December 2018; and Valkov and Others v Bulgaria, nos 2033/04 and 8 others, § 114, 25 October 2011.

- 5Rekvényi v Hungary [GC], no 25390/94, § 68, ECHR 1999-III. See also SAS v France (n 4) §§ 161–62; Cha’are Shalom Ve Tsedek v France [GC], no 27417/95, § 87, ECHR 2000-VII; and Mathieu-Mohin and Clerfayt v Belgium, 2 March 1987, § 59, Series A no 113.

- 6Case Relating to Certain Aspects of the Laws on the Use of Languages in Education in Belgium [Plenary], nos 1474/62 et al, § 9, 23 July 1968 (‘Belgian Linguistics’).

- 7Schwizgebel v Switzerland, no 25762/07, ECHR 2010 (extracts); Fretté v France, no 36515/97, §§ 32–33, ECHR 2002-I; and Glor v Switzerland, no 13444/04, § 80, ECHR 2009.

- 8Clift v the United Kingdom, no 7205/07, §§ 55–63, 13 July 2010; Carson and Others v the United Kingdom [GC], no 42184/05, §§ 70–71, ECHR 2010; and Sidabras and Džiautas v Lithuania, nos 55480/00 and 59330/00, § 49, ECHR 2004-VIII.

- 9Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle, Book V, chapter 3, paras 1131a–b.

- 10Eg Carson and Others v the United Kingdom (n 8) § 61; Biao v Denmark [GC], no 38590/10, § 98, 24 May 2016.

- 11See eg Ponomaryovi v Bulgaria, no 5335/05, §§ 53–55, ECHR 2011.

- 12Roy O’Connell, ‘Cinderella Comes to the Ball: Art 14 and the Right to Non-discrimination in the ECHR’ (2009) 29(2) Legal Studies 211, 218 <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-121X.2009.00119.x>.

- 13As Arnardóttir explains, it is artificial to separate the argumentation necessary to establish the relevant sameness of two people or groups from the argumentation relevant to establishing whether differential treatment of these two people or groups may be justified because their situation is different in some relevant respect. The same qualitative reasoning decides both enquiries. Oddný Mjöll Arnardóttir, ‘Non-Discrimination under Article 14 ECHR: The Burden of Proof’ (2007) 51 Scandinavian Studies in Law 13, 34.

- 14Eg Fábián v Hungary [GC], no 78117/13, § 133, 5 September 2017; Hämäläinen v Finland [GC], no 37359/09, §§ 111–12, ECHR 2014; and Carson and Others v the United Kingdom (n 8) §§ 84–90.

- 15See eg Biao v Denmark (n 10) § 91.

- 16Horváth and Kiss v Hungary, no 11146/11, §§ 116 and 127, 29 January 2013.

- 17Nachova and Others v Bulgaria [GC], nos 43577/98 and 43579/98, §§ 160–68, ECHR 2005-VII; MC and AC v Romania, no 12060/12, §§ 106 and 125, 12 April 2016; and Milanović v Serbia, no 44614/07, §§ 96–97, 14 December 2010.

- 18Opuz v Turkey, no 33401/02, §§ 196–98 and 201–202, ECHR 2009.

- 19Guberina v Croatia, no 23682/13, §§ 92–93, 22 March 2016; Çam v Turkey, no 51500/08, §§ 65–69, 23 February 2016.

- 20Belgian Linguistics (n 6) § 10. In this case, the Court held that it would indeed be absurd to regard Article 14 of the ECHR as prohibiting all instances of differential treatment.

- 21Ibid.

- 22There are exceptions. In Biao v Denmark (n 10) §§ 115–22 and SAS v France (n 4) §§ 115–21, the Court engaged in a rather long discussion about the ‘real’ motive behind the policy under review.

- 23Abdulaziz, Cabales and Balkandali v the United Kingdom, 28 May 1985, § 81, Series A no 94.

- 24Karner v Austria, no 40016/98, § 40, ECHR 2003-IX.

- 25Bah v the United Kingdom, no 56328/07, § 50, ECHR 2011. See also Ponomaryovi v Bulgaria (n 11) § 54.

- 26Kafkaris v Cyprus [GC], no 21906/04, § 161, ECHR 2008.

- 27See eg Kiyutin v Russia, no 2700/10, § 72, ECHR 2011; Konstantin Markin v Russia [GC], no 30078/06, §§ 145–46, ECHR 2012 (extracts); and Alajos Kiss v Hungary, no 38832/06, §§ 41–43, 20 May 2010.

- 28Oršuš and Others v Croatia [GC], no 15766/03, § 157, ECHR 2010; Sidabras and Džiautas v Lithuania (n 8) §§ 56–59.

- 29Sidabras and Džiautas v Lithuania (n 8) §§ 57–59.

- 30Ibid.

- 31The Court has referred to this rule using slightly different phrases, including ‘particularly weighty and convincing reasons’ and ‘particularly serious reasons’. For a thorough discussion of this doctrine, see Arnardóttir (n 2) 649–52 and 654–58.

- 32Smith and Grady v the United Kingdom, nos 33985/96 and 33986/96, § 97, ECHR 1999-VI; Konstantin Markin v Russia (n 27) § 143.

- 33Karner v Austria (n 24) § 41; X and Others v Austria [GC], no 19010/07, §§ 140–42, ECHR 2013.

- 34Konstantin Markin v Russia (n 27) §§ 148 and 151–52.

- 35Schalk and Kopf v Austria, no 30141/04, ECHR 2010; Ratzenböck and Seydl v Austria, no 28475/12, 26 October 2017; and Khamtokhu and Aksenchik v Russia [GC], nos 60367/08 and 961/11, 24 January 2017. See also Andrle v the Czech Republic, no 6268/08, 17 February 2011, on different retirement ages for men and women.

- 36Oddný Mjöll Arnardóttir, ‘Vulnerability under Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights’ (2019) 4(3) Oslo Law Review 150, 157–64 <https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2387-3299-2017-03-03>. It should be noted that the vulnerability of asylum seekers has been discussed in relation to Article 3 of the ECHR and not under Article 14. See MSS v Belgium and Greece [GC], no 30696/09, § 232, ECHR 2011.

- 37Alajos Kiss v Hungary (n 27) § 42; Kiyutin v Russia (n 27) § 63.

- 38See note 37.

- 39The standard expression of this rule is as follows: ‘The Contracting States enjoy a certain margin of appreciation in assessing whether and to what extent differences in otherwise similar situations justify a difference in treatment.’ See, for example, Biao v Denmark (n 10) § 93.

- 40Carson and Others v the United Kingdom (n 8) § 61. See also SAS v France (n 4) § 129; and Khamtokhu and Aksenchik v Russia (n 35) § 85.

- 41See eg Khamtokhu and Aksenchik v Russia (n 35) §§ 85–88.

- 42Eg Molla Sali v Greece [GC], no 20452/14, § 159, 19 December 2018; Biao v Denmark (n 10) §§ 132–33; and Kiyutin v Russia (n 27) § 65.

- 43Eg Andrle v the Czech Republic (n 35) §§ 50 and 60–61. See also Kanstantsin Dzehtsiarou, ‘European Consensus and the Evolutive Interpretation of the European Convention on Human Rights’ (2011) 12(10) German Law Journal 1730, 1733 <https://doi.org/10.1017/S2071832200017533>.

- 44Schalk and Kopf v Austria (n 35) § 105; SAS v France (n 4) §§ 156–57; and Leyla Sahin v Turkey (n 4) §§ 109 and 122. Whether there is in fact no consensus on the permissibility under the ECHR of domestic bans on burqas in public places may certainly be debated, but the outcome of the case was based on the assumption that there is no such consensus.

- 45In Konstantin Markin v Russia (n 27), the Court changed its previous position on the lawfulness of policies restricting parental leave to mothers (see §§ 130–40), and in Christine Goodwin v the United Kingdom [GC], no 28957/95, §§ 84–85, ECHR 2002-VI, the Court overruled its earlier case law on the legal recognition of the gender of transsexuals.

- 46Mjöll Arnardóttir (n 2) 645–51.

- 47Lourdes Peroni and Alexandra Timmer, ‘Vulnerable Groups: The Promise of and Emerging Concept in European Human Rights Convention Law’ (2013) 11(4) International Journal of Constitutional Law 1056; Mjöll Arnardóttir (n 36) 169–71 <https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/mot042>.

- 48Luzius Wildhaber, Arnaldur Hjartarson, and Stephen Donnelly, ‘No Consensus on Consensus? The Practice of the European Court of Human Rights’ (2013) 33(7) Human Rights Law Journal 248.

- 49See eg Khamtokhu and Aksenchik v Russia (n 35) §§ 75, 78 and 85–86; Schalk and Kopf v Austria (n 35) §97; Hämäläinen v Finland (n 14) §109; and Belli and Arquier-Martinez v Switzerland (n 4) §101.

- 50Robert Alexy, A Theory of Constitutional Rights, trans Julian Rivers (Oxford University Press 2010).

- 51Ibid 13–14.

- 52Alec Stone Sweet and Jud Mathews, ‘Proportionality Balancing and Global Constitutionalism’ (2008) 47 Colombia Journal of Transnational Law 72, 147.

- 53Alexy (n 50) 66.

- 54Ibid 395. For Alexy, the relevant legal framework is the German constitution. In this article, it is the ECHR.

- 55Alexy (n 50) 397–98.

- 56Thlimmenos v Greece [GC], no 34369/97, § 47, ECHR 2000-IV; DH and Others v the Czech Republic [GC], no 57325/00, §§ 207–208 and 213, ECHR 2007-IV; and Oršuš and Others v Croatia (n 28) §§ 158–171 and 182.

- 57See eg Sidabras and Džiautas v Lithuania (n 8) §§ 57–58. As noted by the dissenting judges Nussberger and Jäderblom, there was an inexplicable absence of reasoning about less restrictive alternatives in, for example, the reasoning of the majority in SAS v France (n 4).

- 58Alexy (n 50) 102.

- 59Robert Alexy, ‘The Weight Formula’ in Jerzy Stelmach, Bartosz Brożek, and Wojciech Załuski (eds), Studies in the Philosophy of Law: Frontiers of the Economic Analysis of Law (Jagiellonian University Press 2007) 9–27, 9–11.

- 60The weight formula is first introduced in the postscript to Alexy’s book on constitutional rights theory. See Alexy (n 50) 408ff.

- 61Robert Alexy, ‘Proportionality and Rationality’ in Vicki C Jackson and Mark Tushnet (eds), Proportionality: New Frontiers, New Challenges (Cambridge University Press 2017) 13–29, 24–25.

- 62Alajos Kiss v Hungary (n 27) § 39.

- 63Ibid § 42.

- 64Ibid § 44.

- 65See eg B v the United Kingdom, no 36571/06, §§ 58–59, 14 February 2012.

- 66Alexy (n 59) 16.

- 67See Jeffrey J Rachlinsk, ‘Evidence-based Law’ (2011) 96(4) Cornell Law Review 901, 910ff.

- 68Konstantin Markin v Russia (n 27) § 144. See also SAS v France (n 4) § 120; Kiyutin v Russia (n 27) § 66; and Biao v Denmark (n 10) § 125.

- 69See section 2 above. See also Janneke Gerards, ‘The Discrimination Grounds of Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights’ (2013) 13(1) Human Rights Law Review 99, 113ff <https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngs044>.

- 70Examples of cases involving non-suspect grounds include Clift v the United Kingdom (n 8) §§ 73–79; Petrov v Bulgaria, no 15197/02, § 55, 22 May 2008; and Deaconu v Romania (Committee), no 66299/12, §§ 34–38, 29 January 2019. For examples of cases involving suspect grounds, see n 71.

- 71See Petrovic v Austria, 27 March 1998, § 36, Reports 1998-II. See also Konstantin Markin v Russia (n 27) §§ 132 and 139–140.

- 72See the discussion of Alexy’s suitability criterion in section 3 above.

- 73DH and Others v the Czech Republic (n 56).

- 74See Alajos Kiss v Hungary (n 27) § 38.

- 75See Bujdosó et al v Hungary, Communication no 4/2011, CRPD Committee, 9 September 2013, §§ 5.7 and 7.3.

- 76George Letsas, A Theory of Interpretation of the European Convention on Human Rights (Oxford University Press 2007) 24. See also Kiyutin v Russia (n 27) § 69, where the Court discusses the State’s failure to explain the selective enforcement of HIV-related restrictions against foreigners applying for residence permits but not against others. See also EB v France [GC], no 43546/02, 22 January 2008 § 87, where the Court questions the discrepancy between the weight attached to the lack of a ‘paternal referent’ in a case involving a lesbian who wanted to adopt and the weight attached to this factor in other cases.

- 77Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, third party intervention, María del Mar Caamaño Valle v Spain, § 27.

- 78Khatian (n 2) 6–7; Sophia Moreau, ‘Equality Rights and Stereotypes’ in David Dyzenhaus and Malcolm Thorburn (eds), Philosophical Foundations of Constitutional Law (Oxford University Press 2017) 283–304, 301.

- 79Sandra Fredman provides a good overview of the debate in her article ‘Substantive Equality Revisited’ (2016) 14(3) International Journal of Constitutional Law 712, 727ff <https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/mow043>.

- 80Charles Stangor, ‘The Study of Stereotyping, Prejudice and Discrimination Within Social Psychology: A Quick History of Theory and Research’ in Todd D Nelson (ed), Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination (2nd ed, Routledge 2016) 3–28, 10.

- 81DH and Others v Czech Republic (n 56) §§ 213 and 217. See also Emel Boyraz v Turkey, no 61960/08, 2 December 2014. In paragraph 44, the Court speaks about the adverse effects of unjustified dismissal based on sex on a person’s identity, self-perception, and self-respect.

- 82Deborah Hellman, When is Discrimination Wrong? (Harvard University Press 2008) ch 2; Denise Réaume, ‘Discrimination and Dignity’ (2003) 63(3) Louisiana Law Review 1.

- 83Charilaos Nikolaidis, The Right to Equality in European Human Rights Law: The Quest for Substance in the Jurisprudence of the European Courts (Routledge 2016) 3 and ch 4. See also Alexandra Timmer, ‘Toward an Anti-Stereotyping Approach for the European Court of Human Rights’ (2011) 11(4) Human Rights Law Review 707 <https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngr036>. It should be noted that Nikolaidis also identifies the failure to accommodate human diversity as a characteristic feature of unlawful discrimination.

- 84See eg Sophie Moreau, ‘What is Discrimination?’ (2010) 38(2) Philosophy and Public Affairs 143, 147 <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1088-4963.2010.01181.x>; and Shlomi Segall, ‘What’s so Bad About Discrimination?’ (2012) 24(1) Utilitas 82 <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0953820811000379>.

- 85Sandra Fredman, ‘Emerging from the Shadows: Substantive Equality and Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights’ (2016) 16(2) Human Rights Law Review 273 <https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngw001>; Patrick S Shin, ‘Is There a Unitary Concept of Discrimination?’ in Deborah Hellman and Sophia Moreau (eds), Philosophical Foundations of Discrimination Law (Oxford University Press 2013) 163–181, 163.

- 86Nachova and Others v Bulgaria (n 17) § 145; MC and AC v Romania (n 17) § 119.

- 87DH and Others v the Czech Republic (n 56) § 207; As Goodwin points out, these harms too could have been more thoroughly discussed by the Court. See Morag Goodwin, ‘Taking on Racial Segregation: The European Court of Human Rights at a Brown v Board of Education Moment?’ (2009) 170(3) Rechtsgeleerd Magazijn Themis 93, 101.

- 88Konstantin Markin v Russia (n 27) § 141. See also Kiyutin v Russia (n 27) § 64; and Alajos Kiss (n 27) § 42.

- 89See eg Shtukaturov v Russia, no 44009/05, ECHR 2008; and Stanev v Bulgaria [GC], no 36760/06, ECHR 2012.

- 90Burghartz v Switzerland, 22 February 1994, Series A no 280-B; Cusan and Fazzo v Italy, no 77/07, 7 January 2014; and Zarb Adami v Malta, no 17209/02, ECHR 2006-VIII.

- 91Ii in Alexy’s weight formula. See section 3 above.

- 92See Timmer (n 83) 715.

- 93See sections 2.3 and 3 above.

- 94See section 4.2 above.

- 95See section 3 above.

- 96See Leyla Sahin v Turkey (n 4) § 108.

- 97This may explain why the Court remains cautious about obliging States to undertake such transformations. See Fredman (n 85).

- 98In relation to persons with disabilities’ right to inclusive education, the Court has, however, ruled in favour of the State arguing that it is not the task of the Court to determine the resources to be used to meet the educational needs of children with disabilities. The national authorities are, the Court has held, by reason of their direct and continuous contact with the vital forces of their countries, in principle better placed to assess local needs and balance them against competing interests. See eg Stoian v Romania, no 289/14, §§ 102 and 109–110, 25 June 2019.

- 99DH and Others v the Czech Republic (n 56) § 207; Oršuš and Others v Croatia (n 28) §§ 163–71 and 182–83.

- 100Konstantin Markin v Russia (n 27) § 148.

- 101Ibid § 147.

- 102Regarding the ‘extreme vulnerability’ of children who seek asylum, see Tarakhel v Switzerland [GC], no 29217/12, § 119, 4 December 2014; and see Nils Muižnieks, ‘The Right of Older Persons to Dignity and Autonomy in Care’ (Council of Europe, 18 January 2018) <www.coe.int/en/web/commissioner/-/the-right-of-older-persons-to-dignity-and-autonomy-in-care> accessed 11 November 2020.

- 103Alexy calls this ‘discretion in balancing’. See Robert Alexy, ‘On Constitutional Rights Protection’ (2009) 3(1) Legisprudence 1, 15 <https://doi.org/10.1080/17521467.2009.11424683>. Such discretion is relatively uncontroversial. In a situation in which neither interpretation of what Article 14 demands is better than the other, the loss that would result from choosing one over the other is equally serious regardless of which interpretation one chooses.

- 104See eg Konstantin Markin v Russia (n 27) § 147.

- 105See n 103.

- 106Critiques of the consensus rule support this point. See eg Letsas (n 76) 126.