The Norwegian Legislation on Social Sustainability: An Overview of the Transparency Act

Publisert 09.02.2024, Oslo Law Review 2024/2, side 1-15

As the EU awaits the adoption of the proposed Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence, several European countries have already implemented obligations on human rights due diligence at national level. One of these countries is Norway, where the Transparency Act entered into force in July 2022. The Act serves as one of the frontrunners to the expected EU legislation on social sustainability, largely inspired by international frameworks on business and human rights, as well as other countriesʼ regulations of similar matters. Binding legislation in this area, such as the Transparency Act, is an important development as experience has shown that soft law alone is not enough to efficiently combat human rights violations in global supply chains. This article presents the core obligations and principles of the Transparency Act. The aim of the article is to highlight the distinctive characteristics of the Norwegian Act and reflect on where the road of transparency has lead Norway so far, and where it will lead us next.

Keywords

- ESG

- Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence

- Human Rights

- Transparency Act

- Norway

1. Introduction

As the EU awaits the adoption of the proposed Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence, several European countries have already implemented obligations on human rights due diligence at national level. One of these countries is Norway, where the Transparency Act entered into force in July 2022. The Act serves as one of the frontrunners to the expected EU legislation on social sustainability, largely inspired by international frameworks on business and human rights, as well as other countriesʼ regulations of similar matters.

Sustainability is usually broken into three categories: Environmental, Social and Governance (‘ESGʼ). The Transparency Act is a significant step in the right direction to ensure the ‘Sʼ in ESG and thus sustainability in general, as safeguarding fundamental human rights is a prerequisite for sustainability. Binding legislation in this area, such as the Transparency Act, is an important development as experience has shown that soft law alone is not enough to efficiently combat human rights violations in global supply chains.

There is a growing awareness of social sustainability among investors, business participants, consumers and politicians. Due diligence to understand human rights risks is increasingly part of contemplated mergers and acquisitions, and of assessments of possible investments. Nevertheless, we see instances where complex global supply chains in high-risk industries and areas give rise to misconduct, infringements, and breaches—even when and if companies have the best intentions and have undertaken steps to address the risks concerned. Displacement of local residents, infringement of the right to self-determination, poor working conditions and use of child labour, violations of freedom of association and freedom of expression, as well arbitrary or systematic discrimination and inequality are examples of repeated cases. National government regulation that imposes a duty on companies to systematically understand, assess and monitor their operations and supply chains in order to mitigate this risk is therefore essential.

In this article, we first take a look at the Transparency Act and its core obligations in section 2. We present the object and scope of the Act, its overarching principles of proportionality and risk-based approach, before we dive deeper into the requirements of the Act and how they are (presumed to be) enforced. In section 3, we describe some distinctive aspects of the Act. This requires a brief review of similar regulations in other jurisdictions before we highlight the distinctive characteristics of the Norwegian Act. Lastly, in section 4, we provide some reflections on where the road of transparency will lead Norway next.

2. The Norwegian Transparency Act

2.1 Introduction

The Norwegian Transparency Act provides social governance obligations for enterprises to identify and assess risks, as well as implement measures and track the implementation of such measures. The objective is to ensure fundamental human rights and the right to decent working conditions. This obligation refers both to the conduct of the enterpriseʼs own activities, as well as the enterpriseʼs (entire) supply chain. The companies subject to the Act are larger enterprises that are resident and offer goods and services in Norway, and additionally are liable to pay tax to Norway in accordance with internal Norwegian legislation.

The preparatory works to the Act consist of the proposition by the Ministry of Children and Families to the Parliament and the proposition from the relevant parliamentary committee. Serving as a basis for the preparatory works and therefore also being relevant when interpreting the Act, is the report by the Ethics Information Committee (Etikkinformasjonsutvalget), as well as the consequence analysis prepared for the Ministry. As the Act is still quite fresh, there was no recorded practice of it or case law on it at the time this article was written. Preparatory works are therefore central to the interpretation of the Actʼs requirements. Furthermore, we anticipate that coming instructions and guidance by the Consumer Authority will be helpful to understand compliance with the Act as well as the responses to the companiesʼ fulfilment of their reporting obligation due 30 June 2023.

2.2 Object

The Transparency Act is rooted in existing international guidelines and principles for corporate social responsibility, including the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. The Act is not meant to replace said principles and guidelines, as all Norwegian enterprises is expected to implement and comply with these already. This means that companies not covered by the Act nonetheless are expected to perform vigilance assessments in correlation with these principles, also as a push-over effect and expectation from customers. The Act is in this sense meant to enhance knowledge of, and compliance with, the international principles and guidelines.

The Norwegian legislator has stated in the Actʼs preparatory works that the Act has dual aims, albeit with a close coherence between the two. The first aim is to contribute to ensure enterprisesʼ respect for fundamental human rights and decent working conditions. This is stated as the primary object and is sought regulated as an obligation for the enterprises to perform human rights due diligence and vigilance assessments. The second aim is to ensure access to information for consumers, organisations, labour unions and others regarding human rights and working conditions in enterprises and supply chains. This is characterised as a secondary aim and a means to fulfil the primary object. It is, however, a clear signal that the Act is not just an obligation for the enterprises to perform risk assessments and due diligence. The Transparency Act is also meant to be an Act giving consumers, along with civil society and media, a possibility to obtain information from enterprises and make better informed choices regarding human rights and working conditions. This is intended to contribute to a more transparent supply chain down to the end-consumer.

2.3 Scope

The Ethics Information Committee proposed that there should exist obligations to have knowledge of significant human rights risks and to answer requests for information for all enterprises offering goods or services in Norway. A more extensive obligation to conduct human rights due diligence should only pertain to the larger enterprises within the same line of activities. As the hearing rounds and parliament debates proceeded, this view gained much support from civil society as it would increase the focus on fundamental human rights in all parts of Norwegian industry and commerce. However, it was also pointed out that such legal requirements would impose increased challenges for small businesses, which lack the necessary resources to respond to information requests.

The Ministry thus chose to limit the scope of application to only include larger enterprises within the definition of the Transparency Act, intended to be in line with the definition in the Norwegian Accounting Act. The definition of ‘larger enterprisesʼ in the Transparency Act is to be understood as corresponding to the definition in Section 1-5 of the Accounting Act, or those enterprises fulfilling two out of three stipulated thresholds, i.e. sales revenues exceeding 70 million Norwegian kroner (‘NOKʼ), balance sheet exceeding NOK 35 million or exceeding 50 full-time employees (Section 3 litra a). The scope of application was further limited to only include such larger enterprises liable to pay tax in Norway (Section 2), also in line with the scope of application of the Accounting Act. This means that foreign entities are only subject to the Transparency Act if they are liable to pay tax in Norway (Section 2).

With regard to the distribution of goods and services, the Ministry chose a broader approach than the Ethics Information Committee, stating that ‘[…] it should not be decisive for the application of the Transparency Act where the enterpriseʼs goods and services are offeredʼ. The Ministry proposed that the Act should also include larger enterprises that are domiciled in Norway and offer goods and services both within and outside the Norwegian borders. However, for foreign entities, the preparatory works state that the scope of application is limited to the enterpriseʼs activities in Norway, thus aligning the scope with the Accounting Act.

2.4 Overarching Principles

There are two overarching principles that affect the extent of, and approach to, the obligations in the Act. The first is that the expected actions of the enterprise shall follow the principle of proportionality. The second principle is that the enterprises shall have a risk-based approach to their due diligence. Such principles can seem diffuse and difficult to incorporate in specific enterprises. Despite these apparent difficulties, the principles serve as simple and efficient tools for navigating through the forest of human rights due diligence once the code for the specific business has been cracked.

Section 4(2) defines the principle of proportionality, and states that the enterpriseʼs due diligence shall be carried out in a manner proportional to the size and nature of the enterprise, the context of the operations of the enterprise and the severity and probability of adverse impacts. This includes, but is not limited to, the available resources in the enterprise to carry out such due diligence, what kind of service or product the enterprise offers, which industry the enterprise operates in, as well as the geographical placement of the production.

In practice, the principle of proportionality entails that the expectations to human rights due diligence in the enterprises will differ according to the size of the enterprise and the supply chain. To illustrate this principle, we introduce Big Bucks ASA, a large enterprise with several subsidiaries within the fishing industry in Norway. Big Bucks ASA, with its intricate and long supply chain in several countries and an organisation capable of handling extensive due diligence, will—according to the principle of proportionality—have to preform due diligence to a greater extent than Low Bucks AS, a smaller enterprise within the fishing industry with one employee responsible for compliance and only five local suppliers.

Furthermore, the due diligence shall be risk-based and proportionate to the severity and probability of negative consequences. This means that the enterprise shall focus its due diligence on the business areas entailing the largest risks for human rights infringement and poor working conditions. For the Transparency Act to fulfil its object, it is essential to mitigate risks and put an end to conduct that does not pay respect to basic human rights and decent working conditions. In order to do so, the enterprise has to be able to identify the inherent risks within its own conduct and supply chain. It is neither sustainable nor realistic to impose an obligation of complete supply chain control for the enterprise, and it is therefore necessary to approach the obligations according to the risks at hand. Such risk factors may change over time, entailing a frequent assessment from the enterprise of which business areas and parts of the supply chain that pose the highest risks.

Both the principle of proportionality and the principle of a risk-based approach are relevant for mitigating the concerns raised in the above-mentioned debate preceding the adoption of the Transparency Act concerning the Actʼs scope of application. If the Act later becomes an obligation for all enterprises, regardless of their size, the principles of proportionality and risk-based approach will allow the smaller entities to limit their due diligence to what is necessary, and what they are capable of, as well as prioritising the most severe risks if the risks in total seem overwhelming. After all, the enterprises conducting business in the Norwegian market today vary heavily in size and supply chains, emphasising the need for principles governing the scope of obligations in the Act. It is reasonable that No Bucks AS, a small local fishing company with only five employees and one local supplier, if falling within the Actʼs scope of application in the future, shall not be obliged to conduct due diligence to the same extent as Big Bucks ASA or even Low Bucks AS. To sum up, the principle of proportionality means that more is expected of bigger companies with more complex supply chains than of smaller companies under the current application of the Act.

2.5 Key Requirements

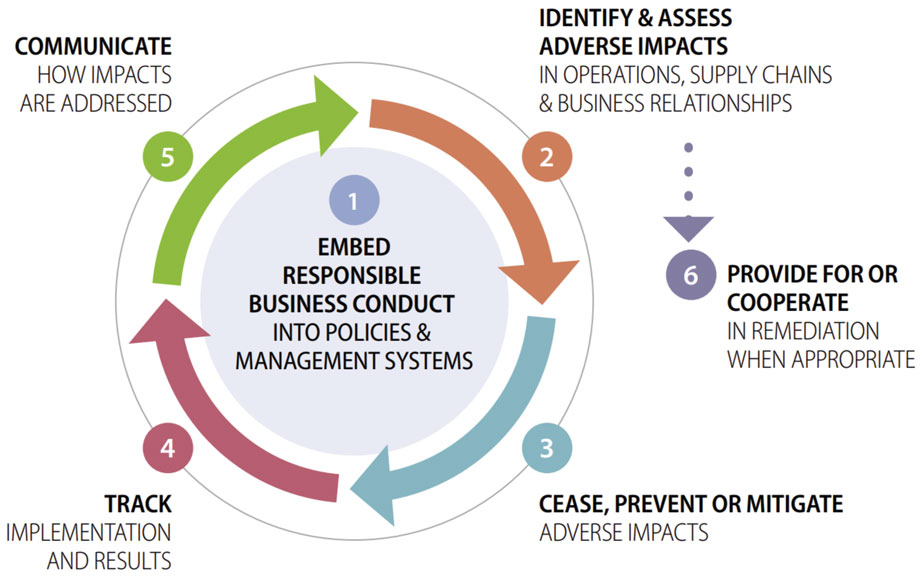

The Transparency Act is, to a great extent, organised according to the same principles as the OECDʼs wheel of due diligence and supporting measures, as presented in the OECDʼs Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct. The said wheel is referred to below and illustrates the different steps of the Transparency Act obligations and the close relations to the international framework that serves as inspiration for the Act. To aid in the presentation of obligations, we have also chosen to divide them in three categories: (i) human rights due diligence, (ii) reporting obligations and (iii) information obligations.

Figure 1

OECDʼs Wheel of Due Diligence Process and Supporting Measures.

2.5.1 Human Rights Due Diligence

The obligation to perform due diligence is stipulated in Section 4 of the Act. Such due diligence shall be conducted in accordance with the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, illustrating the international backdrop to the Act, as further specified in Section 4 litra (a) to (f).

First, responsible business conduct is to be embedded in the enterpriseʼs policies (Section 4 litra a). The obligation anchors due diligence in the enterprise and its corporate management, setting the tone from the top. This corresponds with the first step of the OECD Due Diligence wheel. As illustrated with Big Bucks ASA, the company should put human rights due diligence on the agenda of the board and ensure that the latter adopts a resolution on the Transparency Act. The resolution should be the anchor for further guidelines regarding Big Bucksʼ efforts to comply with the Act and incorporate the guidelines in its daily operations and contracts with third parties. All employees in Big Bucks should have knowledge of the guidelines, ensuring their implementation through the entire company structure.

Second, the enterprise shall ‘identify and assess actual and potential adverse impactsʼ on fundamental human rights and decent working conditions, given that the enterprise has either caused such impacts, contributed towards them, or that the impacts are directly linked with the enterpriseʼs operations, products or services through its supply chain or business partners (Section 4 litra b). The requirement is a parallel to the second step in the OECD Due Diligence wheel.

The first part of the obligation in Section 4 litra b is to identify said impacts. This includes a duty to perform a mapping of all aspects of the business, all operations and business associates, including the supply chain, where there might be an inherent risk and where the risk is greatest. Central risk elements mentioned in the preparatory works to the Act are industry, geography, products and businesses, including known risks the enterprise has encountered previously or probably will encounter. Such mapping can be conducted by creating a structure whereby pertinent information about all suppliers is submitted into fit-for-purpose software that the enterprise can either manage and update internally or outsource to external service providers. Updates should ideally cover supply chain monitoring and be able to provide at least basic alerts based on public information.

The Act applies to the entire supply chain and sets out obligations to map the supply chain based on the principles of risk-based approach and proportionality. If Big Bucks has knowledge of several incidents regarding poor working hours and wages in the factories where the fish is processed and packed for distribution, or is aware that many suppliers in the fishing industry do not comply with relevant working regulations, the company has an obligation to ensure a thorough risk mapping of this supply chain. However, if Big Bucks is not aware of specific risks, it can use trade knowledge, country risk reports and other relevant knowledge as a starting point to uncover where there might be an inherent risk. The Act does not free Big Bucks from its obligation to map its entire supply chain, but, according to the principles of proportionality and risk-based approach, the company can fairly safely start mapping the supply chain in parts where the risk is highest.

The primary risk mapping shall make it possible for the enterprise to prioritise the most important risk areas for the following assessments, converting to the second part of the obligation in Section 4 litra b. This part of the obligation requires the enterprises to assess the discovered risks and impacts. According to the preparatory works to the Act, the enterprise shall carry out prioritisations of actual and potential negative consequences for the purpose of follow-up measures. This prioritisation is to be based on the degree of severity and probability of the information the enterprise has identified through its risk mapping. If the enterprise is not able to remedy all actual and potential negative consequences immediately, a prioritisation is necessary to address the most important consequences first. This is closely related to the identification of impacts as described above. Big Bucks would not be able to prioritise its risks discovered in the fish factories in its supply chain, had it not already identified and gained knowledge of the risk areas and proportional scope of impact.

Third, there is an obligation for the enterprise to ‘implement suitable measures to cease, prevent or mitigateʼ such adverse impacts in accordance with the prioritisations and assessments completed by the enterprise in relation to Section 4 litra b (Section 4 litra c)). This requirement mirrors the third step in the OECD Due Diligence wheel. The aim is for the enterprise to take necessary steps towards stopping activities causing or contributing to negative impacts, based on the enterpriseʼs relation to the negative influence as assessed pursuant to Section 4 litra b. The preparatory works describe that the enterprise shall prepare and implement plans suitable to prevent or reduce actual or potential negative consequences, as well as such consequences directly associated with the business, products or services of the enterprise. For Big Bucks, which has already identified several risks within its supply chain, the next step will accordingly be to take the necessary actions to improve the working conditions for the employees in the fish factories, for example by setting decent working conditions as a term for future business with the supplier or, as a last step and in the event that all avenues of impact are exhausted, changing the supplier to a business that shows respect for basic human rights and ensures decent working conditions.

Fourth, and to ensure subsequent follow-up of the actions implemented by the enterprise in relation to Section 4 litra c, litra d requires the enterprise to supervise the implementation and results of the actions, similar to the fourth step in the OECD Due Diligence wheel. There is no use for Big Bucks to make decent working conditions a term for future business with its supplier, if the company does not ensure that the supplier in fact has conducted the necessary changes in its business and uses the experiences to improve its supplier relations in the future. In accordance with the OECD Guidelines, repeated in the preparatory works to the Act, such actions include the obligation to map, assess, prevent, reduce and, when necessary, support recovery of the occurred damage. The preparatory works state that the enterprise shall accordingly use the experience from the supervision to improve these procedures in the future, giving basis for further development.

Fifth, the due diligence also reaches beyond the corporate walls of the enterprise. Section 4 litra e imposes an obligation on the enterprise to communicate with affected stakeholders and right-holders on how adverse impacts are addressed pursuant to litra (c) and (d), in parallel with the fifth step of the OECD Due Diligence wheel. This provision only covers information to parties affected or potentially affected by the impacts. Nevertheless, the regulation is an important obligation securing stakeholders a line of information where their interests are affected. This has been debated in relation to the proposed regulations on human rights due diligence in the EU, where the lack of stakeholder rights has been criticised. Under the Norwegian Transparency Act, the enterpriseʼs communication with stakeholders will depend on its relation to the negative impact. Where the enterprise has contributed to, or caused, the negative impacts, such communication will be appropriate.

Negative impact is essential in relation to the sixth step, requiring the company to ensure remedy when having caused or contributed to negative impacts. As stipulated in the preparatory works of the Act, and with reference to the OECD Guidelines, the aim of this obligation is to ensure that if the enterprise has revealed that it has caused or contributed to actual negative impacts, the impacts shall be handled by ensuring, or cooperating to ensure, sufficient remedy and compensation. The relevant efforts for remedy will differ from case to case and in accordance with the nature and scope of the negative impact. Big Bucks can, for example, be required to ensure remedy to the employees in the fish factory, as compensation for illegally low wages and poor working conditions, in the event that the company is directly linked to the human rights violations.

2.5.2 Reporting Obligations

In addition to the obligation to perform due diligence, the enterprise shall report to the public to ensure transparency of the due diligence performed. As noted, this reporting obligation on transparency is understood as an inherent requirement for the first: respect for human rights and decent working conditions.

A general requirement to inform the public is regulated in Section 5, stipulating an obligation on the enterprise to publish an account of due diligence conducted pursuant to Section 4 and to make the account easily accessible on the enterpriseʼs website. Section 5 only lists the minimum requirements for the account, and it is up to the enterprise whether they wish to report more thoroughly than described in the regulation. Some of the topics to be covered in the account are a general description of the business of the enterprise, information on routines for handling negative impacts on basic human rights and decent working conditions, as well as negative impacts detected and how the enterprise has handled, or is planning to handle, the specific negative impacts detected. This is to be performed annually or otherwise when there are essential changes in the risk assessments performed by the company.

As an example, Big Bucks should report in its account how the company conducts its due diligence and its internal guidelines and procedures to mitigate risks detected. The company should further, in anonymous form, report on identified incidents on poor working conditions at the fish factory in its supply chain, and how it has mitigated these incidents. At the same time, there is no reason, the way we see it, to not incorporate reporting under the Act into the overall reporting on sustainability for the company. After all, the obligation on human rights due diligence equals the ‘Sʼ in ‘ESGʼ, and work carried out should be seen in relation with steps taken on governance and environment.

Given proper reference to the reporting obligation under the Act, businesses can thus largely benefit from seeing the Act in the context of sustainability, also when conducting risk assessment and implementing measures and follow up. In this respect, Norwegian legislation already contains various regulations intended to influence the business sector to safeguard human rights, such as the Working Environment Actʼs requirements for the working environment and the prohibition of discrimination, Section 3-3 of the Accounting Act on large enterprisesʼ reporting obligations on corporate social responsibility, and Section 5 of the Public Procurement Act on routines for safeguarding human rights and the environment in public procurement.

2.5.3 Information Obligations

As a parallel obligation to the due diligence and reporting obligations, Section 6 stipulates a right for consumers and other parties to request specific information about the enterpriseʼs efforts and procedures related to fundamental human rights and decent working conditions. The obligation of transparency serves as the very inspiration to the name of the Act, resting on the notion that transparency is a prerequisite for ensuring respect for fundamental human rights, enabling the public watchdog to hold companies responsible but also companies to share knowledge and experiences. The information obligation in the Transparency Act complements the existing Norwegian Act on Environmental Information, requiring enterprises to supply information on the environmental impact of their products. One may ask if this form of legislation will become more and more prevalent in ESG legislation, now framing the Norwegian approach to both social and environmental sustainability.

Pursuant to Section 6, and when the enterprise receives a written request, the enterprise is under a duty to provide the person with information regarding actual and potential negative impacts as assessed in Section 4, including both general information and information relating to a specific product or service offered by the enterprise. This means that if Big Bucks receives a request for information on the working conditions of the employees of its supplier, the company is required to answer the request. To ensure good governance, it is advisable for Big Bucks to implement clear guidelines instructing its employees on how to proceed when receiving a request, the timeframe for answering the requests and who is responsible for answering. Big Bucks should draft its routines in line with the requirements stipulated in the following.

If the enterprise is familiar with actual adverse impacts on fundamental human rights, the person will always have a right to information (Section 6(3)). However, given that the enterprise is not familiar with such impacts the request for information can be denied pursuant to Section 6(2) if:

-

The request does not provide sufficient basis for identifying what the request concerns.

-

The request is clearly unreasonable. This is a narrow exemption clause for situations such as harassment.

-

The requested information concerns data relating to an individualʼs personal affairs.

-

The requested information concerns operational or business matters which for competitive reasons it is important to keep secret.

Information pursuant to Section 6 shall be provided ‘in writingʼ and shall be ‘adequate and comprehensibleʼ (Section 7). The enterprise must also provide the information within a ‘reasonable timeʼ (emphasis added), and otherwise in accordance with the following time limits:

-

No later than three weeks after the request for information was received.

-

If the information requested makes the time limit of three weeks ‘burdensomeʼ, the enterprise must provide the information within two months after the request for information was received. However, the enterprise must still within three weeks after the request was received, inform the person of the extension of the time limit, the reasons for the extension and when the information can be expected.

If the enterprise denies a request for information as described in Section 6(2), it shall inform about the legal basis for the denial, as well as about possible further steps after the denial.

2.6 Enforcement

While the public is given an important supervising right in Section 5, the Consumer Authority is appointed as the official supervising authority in Section 9. The Consumer Authority shall conduct its supervision based on the ‘interest of promoting enterprisesʼ respect for fundamental human rights and decent working conditionsʼ (Section 9). Further, Section 9 stipulates that the Authority shall influence enterprises to comply with the regulations, on its own initiative or based on requests from others. The preparatory works characterise this as the model of negotiation, since the Authority shall, as a first step, attempt to negotiate with the enterprises to ensure compliance with the Actʼs requirements. This approach is closely related to the general obligation to provide guidance for all Norwegian public administrative bodies (Section 11 of the Public Administration Act).

As stated in the preparatory works, there is a need for guidance for the Act to reach its intended purpose and ensure compliance. When deciding which public body to act as the supervising authority, the preparatory works state that the Consumer Authority has long and good experience in guiding businesses, and that it will be important for the Authority to cooperate closely with other key expertise environments in the field in order to assist the enterprises in the best possible way. Since the due diligence assessments must be in line with the OECD guidelines, the preparatory works hold that the Consumer Authority is to cooperate closely with the Norwegian National Contact Point for Responsible Business Conduct.

In line with the model of negotiation, and in the event of an enterprise violating the Act, the Authority can obtain a written confirmation that the illegal activities will be brought to an end, or the Authority can issue a decision. If the enterprise is in breach of the decision, enforcement penalties may be issued pursuant to Section 13. Furthermore, if the enterprise has acted in breach with the requirements to publish an account of due diligence or answer a request for information, it may be subject to an infringement penalty (Section 14).

3. The Norwegian Approach to Social Sustainability

3.1 Regulations in an International (and Regional) Context

Norway is not the first country to implement regulations to ensure fundamental human rights and decent working conditions in relation to enterprises and their supply chains. The ‘transparency taleʼ started with the adoption of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs or ‘Ruggie principlesʼ) in 2011. Their adoption constituted a landmark decision, setting out obligations for not only states but also companies to respect fundamental human rights. The unanimous adoption of the principles by the UN Human Rights Council reflected support for the principles from businesses, governments and civil society, after enormous efforts by, amongst others, the then UN Special Rapporteur on business and human rights, John Ruggie.

The UNGPs rest on three pillars: protect, respect and remedy. The guidelines are anchored in the principle that states first and foremost have a duty to protect human rights. One way to ensure protection is to adopt and implement national legislation that safeguards human rights, and subsequently to investigate, prosecute and ensure that victims of human rights violations have an effective remedy. To this extent, states also have an obligation to ensure that businesses do not violate human rights. The principles thus recognise the so-called ‘human rights gapʼ, referring to the fact that states alone, as history has taught us, are not able to ensure universal respect for human rights, nor to protect their citizens from all kinds of violations of human rights. Therefore, the principles impose a responsibility on companies to respect human rights in their activities.

For a long time, Norway met the obligation of the UNGPs by expressing an expectation that companies follow and implement the UNGPs and corresponding OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Both sets of guidelines were primarily followed up by the Norwegian National Contact Point for Responsible Business Conduct and by means of an action plan and stated expectations from the Government. In February 2019, the Government stated:

‘the Government expects Norwegian companies with international operations to be aware of and comply with the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. The companies shall exercise due care and consult those who are affected by the companyʼs activities. Dialogue with indigenous peoples is particularly important in connection with measures that may affect their interests or way of lifeʼ.

For those companies falling outside the scope of the Act, these expectations still apply.

As in most other European countries, national regulatory developments have been fueled by pressure from civil society. This was also the case for Norway, where there was a strong consumer push for information on products and supply chains of companies. The Norwegian initiative for legislation was also supported by larger corporations, including Hydro and Equinor, advocating for stronger legislation to minimise the risk throughout supply chains and for levelling the playing field.

The legislative process leading to adoption of the Transparency Act in Norway was early on split into two parallel processes. On the one side, in 2018, a representative proposal was put forward by a Member of Parliament from the Labour Party for the adoption of a ‘Modern Slavery Actʼ, inspired by the Modern Slavery Act adopted by the United Kingdom (UK). On the other side, civil society was pushing at the same time for the adoption of a due diligence act, similar to that of the French Duty of Vigilance Act. Soon enough, an Expert Committee was appointed in June 2018, with the mandate to analyse whether Norway should adopt a statute act on the obligation to inform and report on ethical business conduct. In June 2019, the Committee presented its first report, testifying to the fact that the Committee had interpreted its mandate broadly, with the Committee subsequently presenting its proposal for a Norwegian Transparency Act in November 2019 to the Ministry of Children and Families. An amended proposal in line with the Act as we know it today was formally presented and debated by the Government and Parliament in April 2021, gathering massive support from all political parties, along with civil society and businesses. After its formal adoption in June 2021, the Act entered into force on 1 July 2022.

As a backdrop to the proposal, and knowing very well that Norway, although proud as a nation but humble as to its size, needs to implement legislation in line with similar regulations in other countries, the Expert Committee set out on a study trip in 2019 to learn more about the international, British and French legislative initiatives. The French Duty of Vigilance Act, adopted in 2017, requires that enterprises conduct due diligence of their supply chain, in line with the UNGPs. The Act covers both human rights and the safety of the environment and applies to companies with 5,000 employees in the company or company group in France, or 1,000 employees in the company or company group in total both in and outside France. The UK enacted its Modern Slavery Act in 2015, with the aim to legislate measures for the prevention of modern slavery and human trafficking. While the Act has a broader scope than the French Duty of Vigilance Act, Section 54 addresses transparency in supply chains, requiring that commercial organisations prepare ‘a slavery and human trafficking statementʼ addressing the steps the organisation has taken to ensure that slavery and human trafficking is not taking place. This includes performing due diligence of its business and supply chains and publishing such a statement on the companyʼs website. The obligation applies to ‘commercial organisation[s]ʼ, meaning all suppliers of goods or services with a total turnover of £36 million or more.

Norway can be said to have landed somewhere between the French and the British Acts. As we have seen, the Norwegian model is in many ways a due diligence act, but with corresponding obligations on reporting that are in many ways framed by its background and the push from civil society. The Norwegian approach may be usefully illustrated by presenting two aspects: complete supply chain and transparency.

3.2 Complete Supply Chain

Under the scope of human rights due diligence under the Transparency Act, businesses are required to carry out human rights due diligence and to map their entire supply chains. This differs from other countriesʼ legislation, which often only includes indirect suppliers when there already is a proven violation. An example of this is the German Supply Chain Act, which was drafted in parallel with the Norwegian legislation. The German legislation regulates companiesʼ responsibility to ensure human rights protection within their own business as well as their direct suppliers, including risk mapping, implementing relevant measures, and reporting on activities. The responsibility includes indirect suppliers when the company receives reports of human rights violations among their indirect suppliers. The relevant assessment is whether there is a human rights risk, including a risk for environmental damage such as water and air pollution (Section 2(2)(9)).

Given the fact that human rights risk is not limited to direct suppliers but often dwells in the shadow of complex and long supply chains, the strength of the Norwegian Act is believed to lie in its holistic approach to the supply chain, recognising that production of goods often includes a complicated supply chain with both direct and indirect suppliers, whereas the risk for breach of fundamental human rights and decent working conditions is as great, or even greater, with regard to the enterpriseʼs sub-suppliers. As a core obligation, a company is thus required to map its entire supply chain, guided by the principle of proportionality and a risk-based approach.

3.3 Consumer Information Rights: Transparency in Practice?

Another possible strength with the Norwegian Transparency Act is the dual approach to holding enterprises responsible for their human rights conduct: a due diligence/reporting obligation in combination with a right for consumers to request information. It is expected that consumers will use this right to obtain more knowledge about the production of consumer goods. However, it is yet to be seen how efficiently the enterprises will adapt to the obligation. The Consumer Authority has published some guidance on the topic, but the area is still open for interpretation. How much information is it necessary to provide if the enterprise receives multiple requests at the same time? Will consumers uphold the right and ask for further information when the first ‘waveʼ of requests has passed? And how will the Consumer Authority adjust the requirements over time and in accordance with the principle of proportionality?

Although there are many questions remaining on the right to information, it is certain that this right, in combination with the enterprisesʼ obligation to know their suppliers throughout the entirety of their supply chain, is a strong tool to ensure corporate responsibility. The consumers will in practice function as a public watchdog, and will, if not by sanctions, be able to stain reputations of enterprises if the latter do not comply with their growing moral and legal requirements. The right to information is therefore a great example of transparency in practice, ensuring that the end-consumer is given the option to make better informed choices.

However, experience has taught us that we cannot solely rely on civil society to impose information and reporting obligations. On the question of whether the UK Modern Slavery Act has been effective, the answer is largely no. There are several reasons for this, but one of them is the reliance on voluntary disclosure and the corresponding burden placed on civil society as public watchdog. Legally binding obligations on companies are needed to ensure compliance. In Norway, this has largely been solved by giving the Consumer Authority the task to control enterprisesʼ compliance with the Act, including an option of imposing prohibitions and economic sanctions. We also observe a tendency of business-to-business obligations, with enterprises mitigating risks and mapping supply chains by actually imposing the information obligation on their partners and suppliers.

4. Conclusion: What Now?

The Norwegian legislator is well aware of the possible inconsistencies between the scope and obligations of the Norwegian Transparency Act and similar legislation governing business and human rights, and in particular between the Act and the EUʼs proposed Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence. With this in mind, it is important to remember that also the Norwegian model is slowly finding its form and that its wrapping might change. The legislator concluded already in its preparatory work that the implementation of the current Act is to be reviewed, especially considering its scope of application and possible alterations to ensure compliance with relevant regulation in the EU.

Awaiting the EUʼs proposed Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence there is thus reason to ask: What now? The Norwegian version of social sustainability has just been set in motion, and practice will show how well it functions. At the same time, one of the most important differences between the proposed EU Directive and the Norwegian Act remains the fact that the latter legislation only covers human rights and labour rights, with the EU taking it one step further by also covering climate and environment, and by putting forward new requirements on good governance. In contrast to the Norwegian Act, the EUʼs proposal encompasses the trinity of ESG.

Norwegian governmental authorities confirm that they expect the EU process to trigger necessary amendments to the Norwegian Act. Norway, as part of the European Free Trade Association, will implement adjustments defined as ‘European Economic Area relevantʼ once adopted by the EU. When and how this happens is not certain, but we expect that changes will include a revision of and possible merger with the Norwegian Act on Environmental Information (Miljøinformasjonsloven), setting out obligations on enterprises to inform about the environmental impact of their products. One can further assume that the EU process will lead to more concrete language with regard to the obligations in the Norwegian Transparency Act, which with its broad definitions will benefit from the incorporation of clearer governance wording.

- 1European Commission, Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and the Council on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937 (COM(2022) 71 final).

- 2Act relating to enterprisesʼ transparency and work on fundamental human rights and decent working conditions (Transparency Act) (LOV-2021-06-18-99 om virksomheters åpenhet og arbeid med grunnleggende menneskerettigheter og anstendige arbeidsforhold (åpenhetsloven)).

- 3NCP Norway, OECD Sectoral Guidance Documents (2016/2017) <www.responsiblebusiness.no/resources/> accessed 20 October 2023. Unless otherwise stated, all URLs referenced in this article were accessed on the same date: 20 October 2023.

- 4Transparency Act (n 2) Section 1.

- 5Transparency Act (n 2) Section 4 litra b; cf Section 2 litra d.

- 6Transparency Act (n 2) Section 3 litra a.

- 7Prop 150 L (2020–2021) Lov om virksomheters åpenhet og arbeid med grunnleggende menneskerettigheter og anstendige arbeidsforhold (åpenhetsloven).

- 8Innst 603 L (2020–2021) Innstilling fra familie- og kulturkomiteen om Lov om virksomheters åpenhet og arbeid med grunnleggende menneskerettigheter og anstendige arbeidsforhold (åpenhetsloven).

- 9Etikkinformasjonsutvalget, Åpenhet i leverandørkjeder (2019) <www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/6b4a42400f3341958e0b62d40f484371/195794-bfd-etikkrapport-web.pdf>.

- 10Oslo Economics, Konsekvensutredning av forslag til åpenhetslov (2021) <www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/c33c3faf340441faa7388331a735f9d9/no/sved/konsekvensutredning-av-forslag-til-ny-apenhetslov_endelig-korrigert-17.2-002.pdf>.

- 11UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011) <https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf>.

- 12OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (2011) <https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/mne/48004323.pdf>. The guidelines were updated in June 2023 (see <https://doi.org/10.1787/81f92357-en>), after the bulk of this article was written, but the update does not introduce any significant changes for the purposes of the analysis herein.

- 13Prop 150 L (2020–2021) (n 7) 31.

- 14ibid 36.

- 15Etikkinformasjonsutvalget (2019) (n 9) 60-62.

- 16ibid 64.

- 17Act relating to annual accounts etc (Accounting Act) (LOV-1998-07-17-56 om årsregnskap mv (regnskapsloven)).

- 18The sales revenue sum of 70 million NOK equals approximately 6 million euros (‘EURʼ). The balance sheet sum of NOK 35 million equals approximately EUR 3 million (April 2023).

- 19Prop 150 L (2020–2021) (n 7) 47 (authorsʼ translation).

- 20ibid.

- 21ibid 110.

- 22OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct (2018) <http://mneguidelines.oecd.org/OECD-Due-Diligence-Guidance-for-Responsible-Business-Conduct.pdf>.

- 23Prop 150 L (2020–2021) (n 7) 109.

- 24ibid.

- 25ibid 110.

- 26ibid.

- 27See eg United Nations Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders, ‘Response to the EU Commissionʼs draft Directive on corporate sustainability due diligenceʼ (May 2022) <https://srdefenders.org/resource/response-to-the-eu-commissions-draft-directive-on-corporate-sustainability-due-diligence/>.

- 28Prop 150 L (2020–2021) (n 7) 110.

- 29ibid 111.

- 30Act relating to the working environment, working hours and employment protection, etc (Working Environment Act) (LOV-2005-06-17-62 om arbeidsmiljø, arbeidstid og stillingsvern mv (arbeidsmiljøloven)).

- 31Act relating to public procurement (Public Procurement Act) (LOV-2016-06-17-73 om offentlige anskaffelser (anskaffelsesloven).

- 32Act relating to the right to environmental information and participation in decision-making processes relating to the environment (Environmental Information Act) (LOV-2003-05-09-31 om rett til miljøinformasjon og deltakelse i offentlige beslutningsprosesser av betydning for miljøet (miljøinformasjonsloven)).

- 33Prop 150 L (2020–2021) (n 7) 116.

- 34Act relating to procedure in cases concerning the public administration (Public Administration Act) (LOV-1967-02-10 m behandlingsmåten i forvaltningssaker (forvaltningsloven)).

- 35Prop 150 L (2020–2021) (n 7) 93.

- 36ibid 91.

- 37Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Norwayʼs Third Report to the UN Human Rights Council on the UP (2019) <www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/a9d8cb7a312d41fe955414f97259b7af/upr_rapport2019.pdf> (authorsʼ translation).

- 38Jette F Christensen, Representantforslag om en lov mot moderne slaveri 41 S (2018-2019) <www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Publikasjoner/Representantforslag/2018-2019/dok8-201819-041s/?all=true>.

- 39Modern Slavery Act (2015).

- 40Loi 2017-399 du 27 mars 2017 relative au devoir de vigilance des sociétés mères et entreprises donneuses dʼordre. For an overview of the legislation, see the article by Jault-Seseke elsewhere in this volume.

- 41UK Home Office, Guidance: Publish an annual modern slavery statement (July 2021) <www.gov.uk/guidance/publish-an-annual-modern-slavery-statement>.

- 42Gesetz über die unternehmerischen Sorgfaltspflichten in Lieferketten vom 16 Juli 2021 (Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz)). For an overview of the legislation, see the article by Jault-Seseke elsewhere in this volume.

- 43Germany, Federal Government, Supply Chain Act (2021) <www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/service/archive/supply-chain-act-1872076>.

- 44UK Home Office, Independent Review of the Modern Slavery Act. Second interim report: Transparency in Supply Chains (2019) 7-8 <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5cb85382e5274a741488a0c6/FINAL_Independent_MSA_Review_Interim_Report_2_-_TISC.pdf>.

- 45Innst 603 L (2020–2021) (n 8) 5.