Policing the Penal Provisions on Repeated and Severe Domestic Violence

Publisert 13.12.2019, Nordisk politiforskning 2019/2, Årgang 6, side 93-110

Abstract

Penal provisions designed to cover repeated and severe abuse in close relationships have been in effect in Norway for the past decade (section 219 of the former Criminal Code, sections 282/283 of the revised Criminal Code). This article evaluates these legal provisions, and in particular, explores the struggle of the police with severe domestic violence. Specially trained police officers and others working in law enforcement, such as prosecutors and judges, have participated as informants. It is insufficient merely to read the legal text to understand what it criminalizes—it is necessary to examine the legal sources. According to the Supreme Court of Norway, a regime of control and violence in a close relationship must be evident. To identify such a regime, the police cannot pay exclusive attention to the specific incidents of physical violence but must focus on what occurs between these events. The totality and complexity of domestic abuse, including psychological violence, is expected to play a central role in police investigation. However, this kind of policing challenges the police role. Police interviews in these cases require particular patience, understanding, empathy and calm. The article will prove that a large proportion of the investigation ends in dismissed cases, but the author will argue that law enforcement is only one side of policing. The police may achieve just as much by means of victim support and prevention measures.

Introduction

Section 219 in the Norwegian Criminal Law, which addresses severe family violence, specifies actions such as “threats,” “coercion,” “restricting freedom,” “violence” or “other violations.” This legislation gives the police a new tool to combat family violence. Previously, only the traditional general provisions against violence were used for this purpose. Section 219 provides victims with the right to counseling at the public expense.

In 2001, a public committee was asked by the Norwegian government to consider how the position of abused women could be strengthened, including by means of stronger legislation. The committee recommended new penal provisions, offering the following argument:

“A limitation of Norwegian criminal law is that the current penalty rules do not capture the complexity of violence against women and children in close relationships. For a woman who is exposed to violence, it does not have to be certain violent offenses that make the women particularly vulnerable. It is the totality of violent offenses—that she lives under the constant threat of violence—that characterizes violence against women in intimate relationships. In the Committee’s view, it is important that the legal justice system does not see the violence and threats as single actions, but captures the totality of the abuse” (NOU 2003:31, s. 144).

The committee proposal was accepted by the government, and the law against repeated and severe abuse in close relationships (Penal Code 219) was adopted on 21.12.2005. Based on the research traditions of police science and victimology, which constitute the theoretical pillars of this study, the article explores the following research question:

To what extent is there compliance between government expectations of Section 219 of the Penal Code and police practice of these provisions?

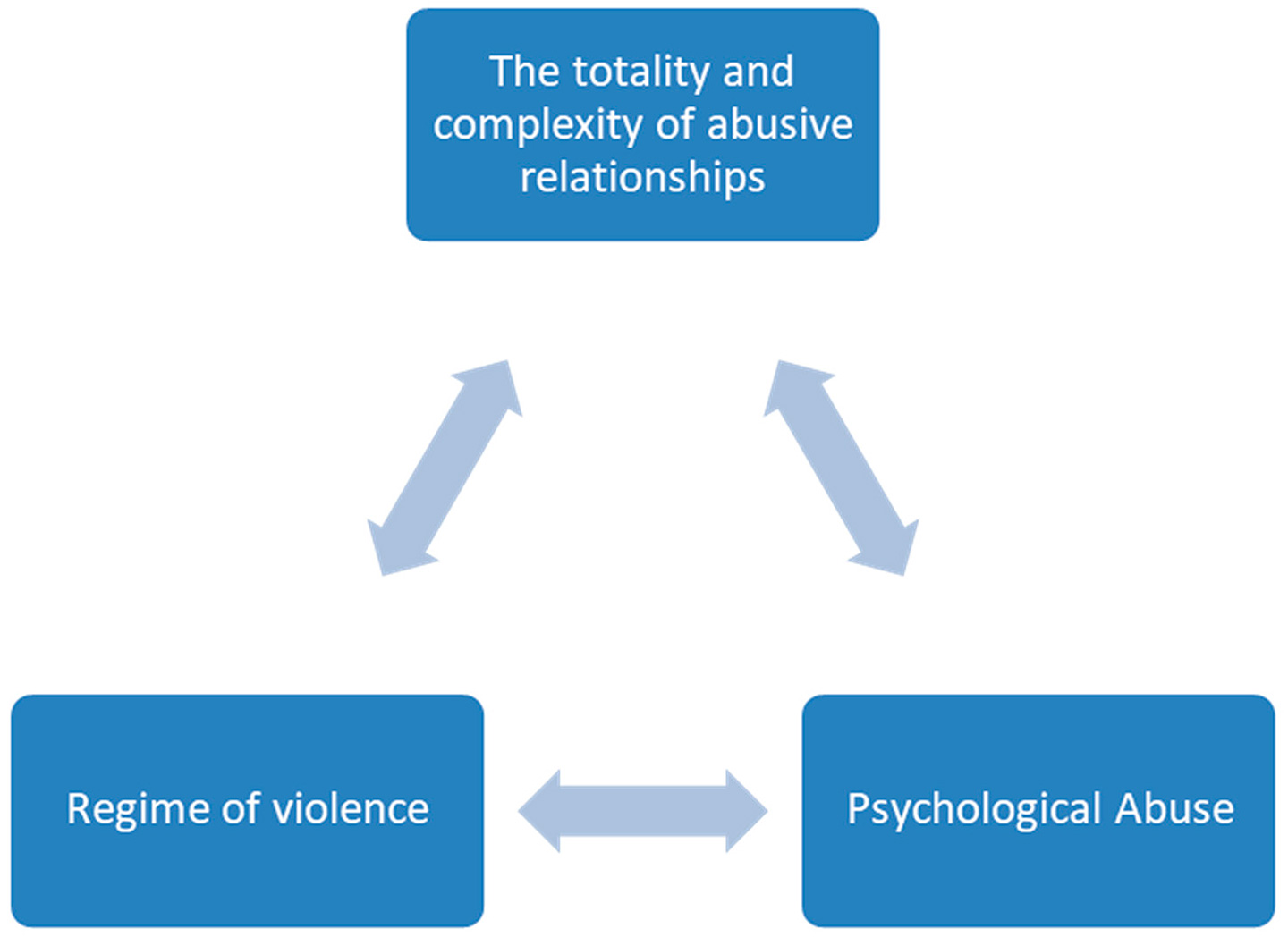

The purpose of this research question is to examine whether the police can employ these provisions according to their intention as expressed in the committee’s legislative considerations. The analysis of data centers on three fundamental dimensions of the provisions:

These dimensions of the penal provision can only be used for analytical purposes—in fact, they are strongly interwoven. The totality and complexity of abusive relationships involves a violent and controlling regime. Psychological violence is an inevitable part of a violent regime, where the whole life situation is characterized by this destructive pattern. Nevertheless, these three dimensions are treated as separate and unique in this article. The article also discusses other important aspects of these provisions, such as the results of investigations and alternative solutions.

Background

Gender differences, violent regimes and common couple violence

Michael Johnsen’s (1995) classic pioneering study “Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence” is a suitable basis for theoretical and analytical assessments of violent and controlling regimes that these criminal provisions address. In Johnsen’s study, a fundamental distinction is drawn concerning domestic violence.This distinction provides a crucial guide for policing family violence issues. The terms “common couple violence” refers to the illegal use of force as a response to conflicts in everyday life motivated by the need to achieve control in a particular situation, rather than a general need to dominate the relationship. However, patriarchal/intimate terror is motivated by the need to dominate and control a partner by all means necessary (Johnsen, 1995). In such cases, the entire relationship is characterized by the exercise of power and domination, and this goes to the core of what the Norwegian Supreme Court requires from the Penal Code 219. The country's highest court has stated that these provisions are reserved for violent and controlling regimes.

Most of the informants in this study tell about men as perpetrators and women and children as victims. The police do not often encounter male victims of partner violence. In a study of police responses to emergency calls about family violence in Oslo, only 6 per cent of those arrested for violence were women (Aas, 2009). These findings might be taken to underpin the common perception that violence in close relationships is committed by men against women. This perception is, however, oversimplified. Gender differences in partner violence are complex matters.

The term ‘patriarchal terrorism’ clearly implies male perpetration of violence and denotes systematic violence exclusively initiated by men as a way of gaining and maintaining absolute control over their female partner; in other words, a type of violent regime with obvious gender differences. However, we have little knowledge about gender distribution of victims of violent regimes in general, as this kind of violence is hard to uncover through surveys. Nevertheless, there is reason to believe that the police get a skewed picture of the gender distribution of violence in close relationships from their experiences with family violence, as there are reasons to believe that male victimisation is highly under-reported. Contacting the police regarding partner violence is probably much more of a barrier for men than women – whether it is dialling the emergency number for immediate help or going to a police station to report violence from a partner. In Bøhm’s (2003) interview-based study of men exposed to partner violence, she found that the men’s self-image and perception of masculinity was an obstacle to talking to anyone about their victimisation. This is also confirmed in a Swedish study which concludes that “The men also highlight double victimization by being victims of both women’s violence and society’s way of viewing their experiences as somewhat taboo” (Hellgren, Andersson & Burcar, 2015, p. 82).

In Straus’ known study “Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations” (2008), partner violence is categorized in three groups: 1. Violence committed by men only, 2. by women only and 3. both partners were violent. In Straus’ data 20 per cent of the cases were “female only violence”, while only ten per cent of the cases were “male only violence”. The most common (more than two thirds of the cases) was that both partners were violent to each other. Bidirectional violence was thus the most common in Straus’ study, and “the aetiology of partner violence is mostly parallel for men and women” (2008, p. 271). In addition, there were more women than men who committed severe assaults in Straus’ study. Nonetheless, violence carried out by men resulted in more physical injury. The theory that female violence is motivated by self-defence is rejected; it explains only a small portion of the total number of partner violence cases because “dominance by the female partner is even more closely related to violence by women than is male dominance” (Straus, 2008, p. 268).

There are, however, some significant limitations to Straus’ study. One is that the data was collected among students, and thus not representative of the total population (Straus, 2008, p. 269). Relationships in this age group have usually not lasted long. Another limitation is that a ‘clinical sample’ is not included. The pattern and nature of violence may vary a lot among those who seek assistance because of abuse. The typical violence in the student sample is occasional episodes of less serious violence, cf. what Michael Johnsen refers to as ‘common couple violence’. By contrast, patriarchal terrorism, or intimate terror, is rare and difficult to capture in such a “community sample” (Straus, 2008, p. 271).

Straus’ distinction between “clinical sample” and “community sample” echoes the ideological division between the “gender neutral” and the “feminist-orientated” research traditions on violence in close relationships (Pape & Stefansen, 2004). The gender-neutral tradition is often based on quantitative data (survey studies) and captures other perspectives than the feminist-orientated one. In the latter research tradition, qualitative interview studies of clinical samples are more common. In the gender-neutral tradition, partner violence is regarded as a type of conflict management among equal partners, where both genders are victimized to more or less the same extent. The feminist-oriented tradition have been criticised for unilaterally studying partner violence in contexts where men are the perpetrators and women the victims, and for perceiving men’s violence against women in close relationships as exclusively motivated by the want for power and need to control and suppress women (Haaland & Clausen, 2005). On the other hand, survey studies do not easily capture the balance of power in close relationships – the context, motives and effects of the partner violence in question are rather unavailable for this kind of research approach.

In a survey on “hidden violence” in Oslo, about as many men as women reported exposure to partner violence (Pape & Stefansen, 2004, p. 79). Contrary to Straus’ results, far more women (12 per cent) than men (3 per cent) stated that they had been subjected to severe forms of physical violence from their current or former partner in the Oslo-survey (Pape & Stefansen, 2004, p. 79). Another Norwegian survey, the national survey on “Violence in relationships” found no significant gender differences regarding vulnerability to various forms of physical abuse and threats from one’s partner (Haaland & Clausen, 2005, p. 59). Approximately 27 per cent of the women and about 22 per cent of the men partaking in the survey reported having experienced threats and/or violence from their partner. However, about four times more women than men had been subjected to violence with a high potential for serious injury (Haaland & Clausen, 2005, p. 60). Both these Norwegian studies show that there are small gender differences in minor forms of violence, but significant gender differences when it comes to severe assaults; significantly more men than women commit severe violence against their partner.

Methods

This study consists of both qualitative and quantitative data. The primary methodological approach for this study consists of focus group interviews with 43 informants in the following two main categories: Police investigators (23 informants) and other legal actors (20 informants). The latter group, who represent a higher hierarchical tier in the legal system, consists of informants from the prosecutors’ offices and courts (four district attorneys, three police attorneys, 12 judges from the court and one counselor). The police investigators regularly employ this penal provision and are specialists in family violence. Most work in teams where they work exclusively on such cases. The police investigators were interviewed in five focus groups. The other legal actors were interviewed both individually and in groups (six interviews). All informants were interviewed at their own workplaces. The interviews were conducted periodically from September 2015 until April 2016.

The informants were recruited from diverse geographical locations, and the interviews were conducted in the Norwegian cities of Oslo, Fredrikstad, Sandvika, Lillestrøm, Bergen, Skien and Trondheim. Police officers were also recruited through personal contacts. During twenty years of teaching and police research at the Police University College in Oslo, the author has gradually built a large network of contacts in the police force, which has been useful for police research. The other legal actors were formally contacted through letters requesting interviews.

The police investigators mainly responded to questions relating to the aforementioned dimensions of these legal provisions and the challenges they encounter in this work. The other legal actors, who encounter this police work in various ways, responded to questions about their evaluations of police work and the challenges they confront regarding Section 219.

A focus group interview is a structured qualitative research interview with informants gathered in groups. There are several advantages of gathering informants (Johannessen, Tufte & Christoffersen 2015). The researcher gets the opportunity to bring forth variations and breakthroughs in experiences and perceptions between the informants. The informants are encouraged to reflect on what the others have conveyed. Focus group interviews also have an efficiency rationale by bringing together many informants within the same time span. The author met the informants in a meeting room at their workplace and started the interview by providing information about the purpose of the research project, which topics were to be addressed and about the participants’ voluntary participation.

The interview guide formed the framework for the talks, but with flexibility with respect to the informants’ own experiences. In the authors’ view, the most successful interviews take place when the informants’ views and experiences rather than a rigid interview guide are set at the center of the conversation (Aas, 2017). The interviews were conducted as a dialogue between researcher and informants, which is typical in fieldwork (Wadel, 1991). The dialogue has the capacity to penetrate beneath the surface and obtain more credible reflections from informants. This is especially important in interviewing police practitioners, who may want to hide misconduct in their duty.

The interview data are organized according to typical content analysis, in which data are categorized by topics that recur in the material. A typical starting point for qualitative interviews is a set of issues addressed by the informants. Meanwhile, the researcher needs to be open to the diversity of experiences, opinions, reflections and attitudes that the questions elicit. The interview data in this study consist of 110 pages of transcribed material, from which the creation of meaningful categories is attempted. Some of these categories will be presented in this article (Aas, 2017).

The limitations of this study are related to those of qualitative methods as a scientific method. In qualitative interviews, the number of informants is limited to a few and the research faces obvious generalization problems. The conclusions of a few cannot be applied to all. However, the strength of qualitative methods is to achieve an in-depth understanding of phenomena rather than a breadth of knowledge. Yet it is likely that the data material reveals some key patterns and veins in police practice and the challenges with the provision designed for repeated and severe abuse in close relationships (Aas, 2017).

People in extremely vulnerable situations are of primary importance in this study. Therefore, it is crucial that no stories can be traced back to identifiable individuals. This was also an ethical issue for obtaining the approval of the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) for this study.

The numbers of cases presented in this study are taken from police databases. The searches were conducted at various times during 2016. Access to the databases was approved by the National Police Directorate. The numbers on police decisions represent all the police reported cases of section 219 in 2014 (2715 cases). Previous studies have shown that the number of police decisions do not vary much from year to year (Aas, 2014; Aas, 2015).

The numbers represent police reports that the police have recorded in the register for criminal cases (BL). The reports are registered by both police patrols and police investigators who have received a report primarily from the victim or child welfare service. When the police officer registers a report in BL, the report is coded with a specific statistics group representing the type of crime. Police officers coding with an incorrect statistics group is the main source of error in this registration. A report about a regime of violence may be incorrectly coded in a statistic group for single cases of violence. The dividing line between a violent regime and episodic incidents of violence is fluid and it is impossible to estimate the size of this source of error. The author has retrieved the numbers from PAL-STRASAK. PAL means the Police Analysis and Management Tools. STRASAK is the nationwide criminal case register (and the information in STRASAK is produced in BL). (Bjerknes & Hoff Johansen, 2009).

Results

A complex and challenging legal provision

There is little doubt among the informants that the legal protections against domestic abuse are complex and challenging for the police to enforce. This totality and complexity appear almost limitless if we believe District Attorney 1: “It's a whole life that is supposed to be described during a short trial.” Judge 1 concludes in this way: “What is difficult with these cases is that almost everything is relevant (...) the whole lives of these people become relevant. It gets very difficult to control and restrict these cases.”

Police Officer 1 argues that it is unwise to keep a tight framework of relevance in the totality and complexity of interviewing victims: “Even if they talk about something that is not really interesting for us, we should not stop them—for suddenly a point or another may pop up that we need to note.” The police officers refer to meticulous interviews, often of several hours' duration, to capture the entirety of the abusive relationship, as Police Officer 2 explains: “Thorough questioning are the key words here. You may not reveal all points during the first interview—maybe the third or fourth.” Several interviews with the same person may be necessary to go through her story and to create sufficient trust between the police officer and victim.

The challenge of identifying a pattern of abuse and a history of maltreatment is described as follows (Police Officer 3): “It’s a difficult thing to talk about—they may not be able to articulate it in the beginning.” For the same reason, several interviews might be necessary, considering that it takes time to break through a wall of shame and speechlessness. Officer 4 elaborates:

“You do not reveal the psychological violence of someone who has lived in it for 15 years by talking to them once. They are so mentally degraded and have displaced so many details through so many years and have had more than enough to survive in their daily life. Sometimes we should have done more. We should have spent more time listening to the victim—because they need time. I have had victims who were unable to say a single word.”

An additional challenge is interviewing victims who are traumatized. Officer 5 explains:

“It requires more questioning because you need to tidy for them. They are not capable of doing it themselves—it takes a lot from the police officer. They cannot hold the thread of an explanation—what we think is important and what they think is important. So, you need to give them space and room enough to express what they think is important and that we get enough of what we think is important. You have to be curious and patient.”

It is obviously demanding for a police officer to extract comprehensive and coherent information from victims who suffer from traumatic stress. Typical reactions that the police could face in this connection are apathy, impaired concentration, anger and irascibility, problems with logical thinking and lack of decisiveness (Skants, 2014). If a police detective wants to gain trust under such circumstances, and create an atmosphere of dialogue and openness, it takes considerable patience, calm and empathic skills.

Police Officer 6 advocates writing the indictments differently in these cases. Instead of creating a list of single events, she suggests a complete and synoptic description of the whole story of abuse. Such a presentation may ensure that the totality and complexity are captured in a better and more credible way than a series of bullet points, which is now the practice. This officer claims that a focus on the totality and complexity, rather than just on individual events, may strengthen the victim's credibility. This approach brings a context to the abuse and highlights the question of why many victims remain in relationships with abusive partners. It may more easily highlight the victim's psychological dilemma. District Attorney 2 claims that there is too strong a focus on concrete details in police interviews:

The fear should be tested and documented. There has probably been an overemphasis on the physical and visible. That’s understandable because this is the easiest to demonstrate and to prove. There has been less focus on what has occurred in the meantime between the various physical attacks. That’s where you find the fear—the fear of what happens next time.

In line with these reflections, the scope, approach, and duration of the abuse should be at the center of the investigation, not primarily individual events. Furthermore, District Attorney 2 argues that emphasizing accurate times and locations of incidents of violence may undermine the totality of the story of abuse. It is easy to sow doubt about exact times and locations of single incidents, and the case will take an unfortunate sidetrack.

According to the Vice-President of the Director of Public Prosecutions in Norway, the content of the abusive pattern and process is too seldom conveyed to a court (Sæther, 2016). Nevertheless, single events cannot be forgotten in the indictment. The whole and the parts of a story of abuse are in a mutual and dialectical relationship with each other. It is the incidents that create the simultaneous totality that sheds light on individual episodes.

Intimate terrorism

According to Johnsen’s concepts of “Patriarchal terrorism and Common couple violence” (Johnsen, 1995), we can state that episodic/situational partner violence refers to couples who experience one or several less serious violent incidents, often as a result of a harrowing conflict. Episodic violence does not constitute a pattern of violent assaults, and the perpetrator is almost as likely to be a woman as a man (Haaland & Clausen, 2005). In other words, there is no clear gender orientation in this form of violence. Furthermore, couples who have experienced this type of violence are described as equal (Haaland & Clausen, 2005). Intimate/patriarchal terrorism has a completely different pattern—a system of oppression and repeated abuse. The term “patriarchal” highlights men as the main perpetrators. Their relationships with partners are described as “asymmetric,” which means an absence of equality and a huge power difference between the parties (Haaland & Clausen, 2005).

It is obviously impossible to draw clear boundaries between these analytical categories of domestic violence, and there are significant shades and gradual transitions between these ideal types. When a destructive relationship moves from episodic violence to intimate terrorism is an open question. Nevertheless, Johnsen (1995) demonstrated that of those who had committed less serious offenses against partners, only about six percent committed more serious violent acts against the partner during the following year.

When the police assess whether a violent regime exists and apply the Penal Code, both an inner and an outer understanding of abuse should be established. The outer, or objective understanding, is in its pure form a summary of incidents by which to decide whether there is such a regime. If the police choose an inner and interpretative perspective and seek to understand the reality from the victims’ point of view, a quantitative approach to defining an abusive pattern appears less relevant. According to District Attorney 2, in an abusive relationship, “the violence characterizes daily life—even when it is not practiced.” Police Attorney 1 describes the insecurity and uncertainty of an abusive relationship as follows:

Maybe it does not happen every time, but the expectation or fear that it may happen (…) an abuser who threatens, but does not exercise violence…maybe he does it on occasion. It may be enough to establish a pattern—that she lives in the expectation that it may repeat, but it may not always do so.

District Attorney 3 elaborates:

The victim adapts and changes (…) turns into a more passive role—does not discuss it— has no objection… is being oppressed... This is important to point out in relation to such a regime.

It should also be noted that this penal code does not require repetition of the violence. If the act is sufficiently serious, it may create a persistent regime of fear and submission. A central question in the informants’ minds was whether there was a misunderstanding in the use of these legal provisions. Do the police use this penal code when traditional provisions against violence should have been preferred? Three decades ago, a Norwegian study of abuse reported to police documented that most of the women who reported their partner had experienced recurring abuse from the same partner (Aslaksrud & Bødal, 1986). Another study demonstrated that it took an average of 1–2 years from the time a victim experienced the first assault by a partner until she told anyone about it (Hoyle, 1998). In the experience of Police Officer 7 individual episodes hide more abuse, and she justifies the use of Section 219 as follows:

If you choose 228 (penal code for simple assault) you may fail to examine…investigate. If you go instead for Penal Code 219, you’ll take a more thorough approach. Then you get the opportunity to illuminate the situation. Usually, it’s more than they immediately tell.

According to some informants, domestic violence sometimes appears similar to simple assaults on the surface, but if the police dig further, a regime may soon appear. The choice of questions asked of the victims is crucial to the determination of a penal code. Judge 2 puts it this way: “In many of these cases, a regime is not being investigated—then they end up as 228 (penal code for simple assault) here in court.”

Psychological violence in the police reports

In O’Leary and Maiuros’s (2001) anthology of research on psychological violence in intimate relationships, this type of violence is identified as a distinct phenomenon, and as a separate and identifiable part of abusive relationships, despite the often close link of psychological violence to physical abuse. Maiuro (2001, p. ix) outlines four dimensions of psychological violence:

-

Denigrating damage to partner’s self-image or esteem.

-

Passive-aggressive withholding of emotional support and nurturance.

-

Threatening behavior: explicit and implicit.

-

Restricting personal territory and freedom.

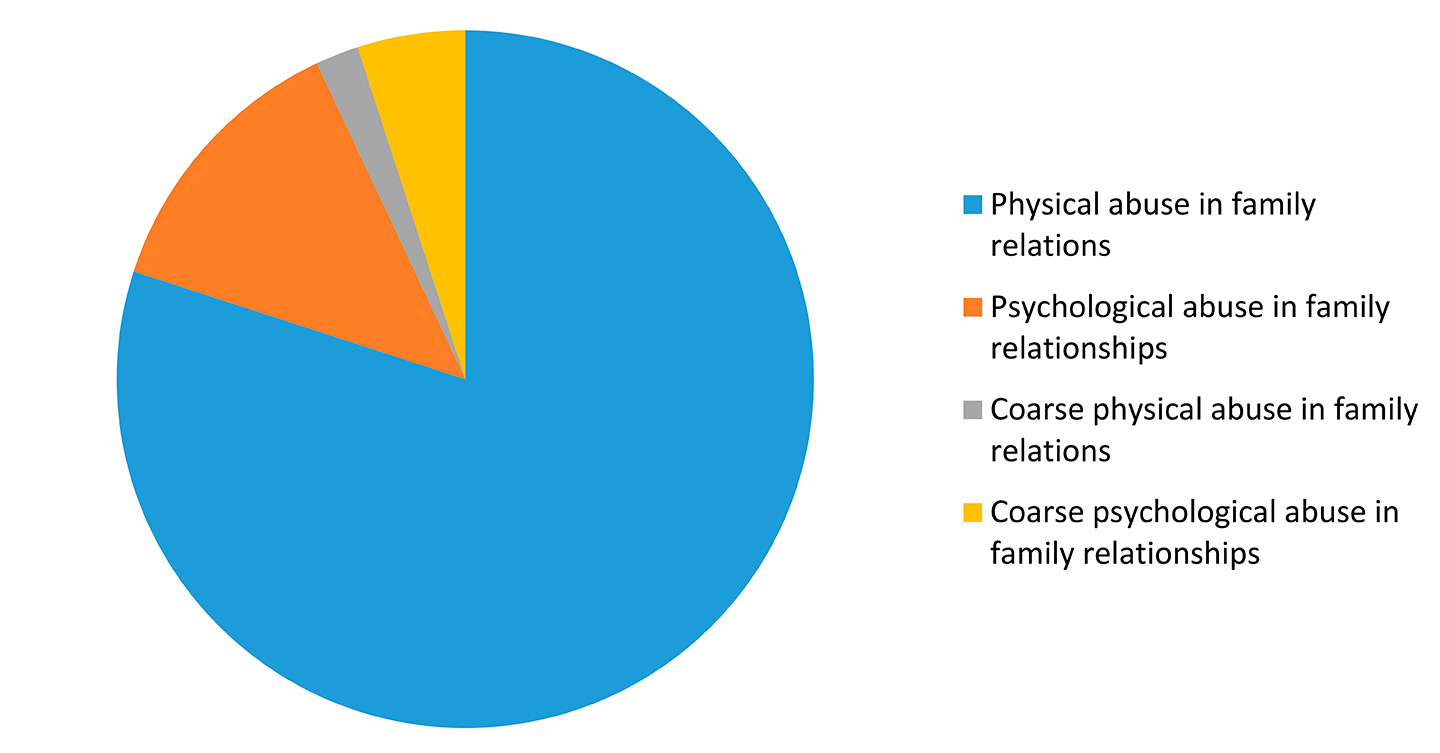

These forms of psychological abuse are largely identifiable in the police reports as well. However, for Penal Code 219 to apply, these actions must constitute a pattern and represent a regime. How much of the abuse in close relationships reported to police is limited to psychological violence? Figure 1 may provide an insight.

Figure 1.

The proportion of physical and psychological abuse in all police reported cases (section 219). 2014 (Percent).

N=2715

As Figure 1 demonstrates, there are two categories that are solely rooted in psychological violence. Eighteen percent of the caseload is represented by these two categories. An example of psychological abuse, in the form of controlling behavior, is described by Police Officer 8 as follows:

This is a 10-page interview transcript—and it’s written here that one evening she was at home; she had remembered to do all the things that she knew her husband wanted her to do. She had cleaned the apartment, made pancakes, bought the things in the supermarket that she knew he wanted. When he got home, she sat on the exact spot on the sofa that she knew he wanted.

This investigator adds something significant to this story: “There is no offense here—no violence here.” The story in itself is of no interest to the police. The way it is told describes no offenses, but in a violent regime, single stories must be interpreted in a context to be given meaning. In both the law and jurisprudence there is little guidance on the definition of psychological violence. Police Officer 9 takes this view: “It’s very difficult (...) how do we define what should be a criminal offense and what is not?” In this interview, infidelity was mentioned as an example. Such actions are not criminalized but still have the potential to cause great psychological harm. Police officer 10 explains how she reacts to stories about infidelity:

That’s when you have to dig—it’s up to us to find out. What does this do to you? What is he saying? What happens when he is cheating? Do you confront him? How does he react when you confront him? Does he tell you about it? Does he brag about it? You have to start digging and be curious, figure out all approaches to find the pattern.

By this reasoning, the objective action of “infidelity” is not the center of police attention, but rather they consider the motivations and expressions to the partner. If the action is motivated by the need to offend and humiliate the partner, it may become the subject of police attention and be characterized as psychological abuse. It is not expedient to seek actions that should be classified as mental abuse. When assessing psychological abuse, what matters are the intentions behind the actions.

The appearance of the victims

The appearance of the victims seems to be significant in the legal process. Judging their credibility is central to the police investigation. Police Attorney 2 claims that: “It’s a challenge when the victim does not show much emotion.” She adds that it boosts credibility when a victim cries while testifying in court. District Attorney 3 recounts the story of a victim who was distrusted by the court. The trial was arranged a long time after the police interview. The woman had reestablished herself, and no longer appeared to be a typical victim. Her former husband was consequently found not guilty.

A previous study may shed some light on this issue. Bollingmo et al. (2008) found that the way in which victims of rape present their tragic experiences had a significant impact on credibility ratings of both police investigators and ordinary people. As a part of the study, professional actors were hired to play the role of victims; they reported a rape assault with three different emotional expressions. One version was performed in a neutral way, the next while displaying emotions of sadness and despair, and the third in a tone of excitement. The video clips were shown to police officers, judges and lay people (i.e. students) who were asked to answer questions about their interpretations of the stories. When the “victims” cried, they were considered far more credible by both police officers and lay people, but not by the judges.

Judge 3 in this study explains that he finds the evidence supporting the victim’s testimony far more important than whether the victim appears credible or not—whether “she seems touched or not.” Bollingmo explains that judges have their own strategies when they reach their decisions, and that their professional experience and expertise protect them from prejudice. However, such professional immunity did not apply to police investigators (Bollingmo et al., 2008).

A counselor in the interview material may bring nuance to this issue. She claims that the victim’s credibility is central in cases where the court is struggling with doubts about the evidence. In her experience, victims who express their stories in a sober and nuanced way, even correcting certain information in the defendant's favor, emerge as particularly credible. On the other hand, if the victim describes her terrible marriage, and tries to “minimize her own role” as Judge 4 puts it, she reduces her own credibility at the same time. District Attorney 2 links the issues of evidence to his experience that the relationships that are introduced to a court cannot be drawn in “black and white,” but “shades of gray.” Acquittals in these cases are related to the fact that “they find out that neither of them was better than the other.” He is supported by Judge 5, who also connects acquittals to reciprocity between the parties as follows:

They press charges against one party in a marriage that has been a living hell for both partners—because the woman reports her husband after they were divorced. The police investigator believes in her explanation. Then it turns out that there is reciprocity in it. How can we really judge one of them when she has slapped him an equal number of times and yelled and slammed doors. Yes, there is a regime of terror in that marriage—no doubt about that, but it is mutual.

This judge raises the following principal issue in connection with the notion of reciprocity: “How much reciprocity between the parties can you tolerate in order to judge one of them? I find it terribly difficult to handle.” The legal provisions designed to address repeated and severe abuse in close relationships obviously need a perpetrator and a victim. If the judge finds equality that characterizes the relationship, these roles are eliminated, and the use of the provision becomes irrelevant. The victim's behavior is also central to Police Officer 11, who describes her experiences with the victims in this way: “Some of them are terrible to deal with —amazingly frustrating ladies to handle, some of them. But they are vulnerable.”

The police role

As long as the police are obligated to understand the complexity of abusive relationships, and to consider the violence from the victim’s point of view, their role will easily move beyond their traditional tasks. Law enforcement is just one side of policing. The police also play the roles of nurses, social workers, psychologists and other roles by virtue of their unique authority (Bittner, 2005). This is not primarily because the police want these roles, but rather the contrary—because the tasks that the police face often require such roles. Several of the informants point this out, and Police Officer 12 describes the diversity of her family violence work in this way:

I would say we have several hats. We are investigators, we are family therapists and we are psychologists. We wear all these hats for the victim, and sometimes the suspect too. He also needs to talk (…) We wear many hats, and this takes up our time. It’s not just a conversation about violence, but also about the overall family structure. It is about kindergarten, school, work and how those involved generally get along with friends. It’s so complex—it’s so much….and they need advice. What are they going to do now? We have to put them in contact with several agencies—this work is so much more than interviewing—it’s so incredible how much more we arrange for those involved.

She recounts further cases where she has established a good rapport with a suspect or a victim, and she may receive frequent phone calls from them. She adds that she avoids rejecting anyone because she finds it important to have a good relationship with those involved. In this connection, she describes a young man in despair who had been mistreated by his stepfather. The young man came repeatedly to see her at the police station because he needed to talk. He developed great confidence in her as a police officer. He wanted to talk to her about his opportunities, who he could contact for help, and similar matters. The police role can also resemble the role of a therapist when they attempt to raise the awareness of the victims. An example is given by Police Officer 13, who revealed that she helps victims to put words to what they have been through by explaining the typical processes in a violent relationship. She claims that some victims get “aha experiences” from such insights.

Results of investigations

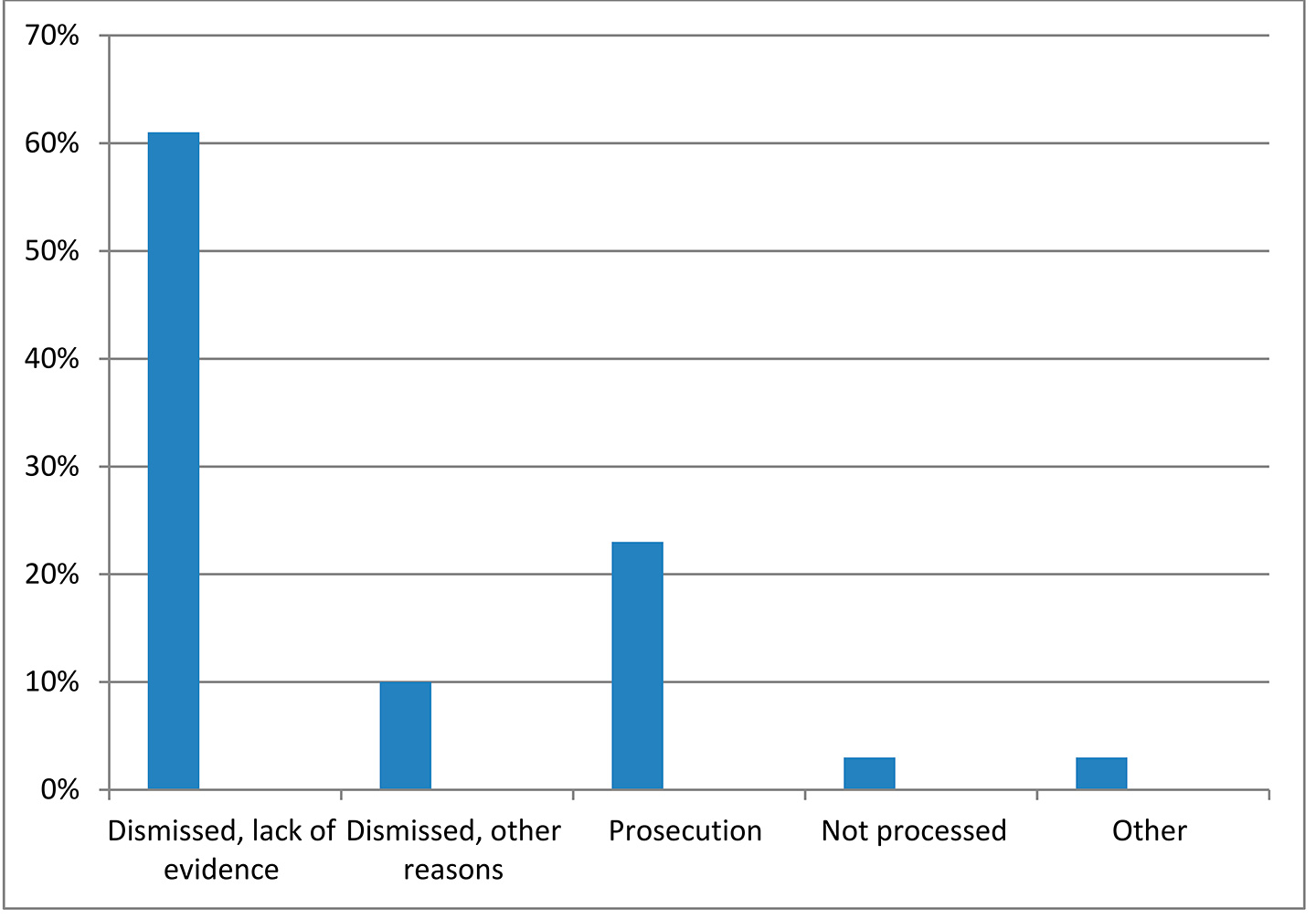

Interview data in this article refers to various issues concerning the investigation of violence in close relationships. A significant question connected to this concerns the results. Figure 2 provides an illustration.

Figure 2.

Police decisions in accordance with repeated and severe domestic violence (Section 219). Percentages of all police reported cases. 2014.

N = 2715.

Overall, dismissed cases dominate this figure. As Figure 2 demonstrates, more than 70 percent of all section 219 cases in 2014 resulted in a decision not to prosecute. The most common specific reason for the dismissals is “insufficient evidence.” It means that the evidence obtained by police is insufficient for prosecution, and the police must suspend the legal process. Ten percent of all cases were dismissed for other reasons. Slightly over one in five of the police reports ended in an indictment. The fact that three percent of the reports from 2014 have not yet been settled (in May 2016) says much about the use of time in some cases. It should also be noted that these figures have remained stable over several years (Aas, 2014).

Previous studies of policing domestic violence (Aas, 2014) have documented that repeated abuse in close relationships is more difficult to prove than other family violence (according to traditional penal provisions). The apparent reason is that it is easier to document individual cases of violence that have occurred recently than repeated assaults further back in time. District Attorney 1 attributes high dismissal numbers primarily to the fact that Section 219 relates to crimes that take place behind closed doors with low transparency. That is why the police often struggle to establish a sufficient pattern of evidence. There are strict requirements for the police and prosecuting authorityin this connection. The latter is not permitted to bring any case to court without being convinced of guilt.

It should also be noted that the high number of dismissals must be considered in light of the number of cases that rest on the shoulders of the police. The number of Section 219 reports has increased dramatically over the past decade. The increase in police family violence investigators has far from kept pace. Given this shortfall, many informants express despair.

Police Officer 10 clearly expresses such despair when she says that she encodes reports into another penal code just to dismiss the case. In this way, it is easier to dismiss the case without conducting any investigation. She explains; “I'm looking for reasons not to investigate – and that is dreadful”. What is special about this statement is the fact that it is not the nature of the cases that is placed in focus, but rather the need to dismiss the cases and remove them from the case load and thereby reduce the work pressure.

The workload for these cases primarily consists of repetitive and comprehensive interviews of the victims, writing a lengthy interview transcript, conducting a number of other interviews with those in the victim’s social network, preparing for organized questioning of children, and obtaining and reviewing extensive documentation from external agencies. The informants for this study also refer to strong variations in commitment to combatting family violence between various police stations in Norway.

Discussion

A reflection on the dismissals

The interviews with the police investigators and the other legal actors raise a number of topics for discussion. If we start out from the findings that demonstrate the high number of dismissed cases, the total caseload is an obvious explanation as the informants pointed out. It is clearly demanding for the police to prove a pattern (a regime) of abuse.

An important question is whether the police should produce more cases for prosecution and thus reduce the number of dismissed cases. The counselor in the interview material claims that the police should not be so afraid of acquittals in these cases. “Let the court pass judgement” she says. However, there are strict requirements regarding the evidence that the police are supposed to bring to court. The Director of Public Prosecutions in Norway has instructed that the Public Prosecutor must:

be entirely convinced that the defendant is guilty in order to institute an indictment, and to be of the opinion that the guilt can be proven in court. The instructions issued by the Director of Public Prosecutions with regard to the evidence required for an indictment to be instituted mean that the prosecuting authorities must base their judgements on the same threshold of evidence as applied by the courts in cases of conviction (Riksadvokaten, 2012).

The numbers of dismissals may also depend on the working logic of the police. How does the “The Police Gaze” work in these cases, if we make use of Finstad’s analytical term when exploring how the police interpret, comprehend and act (Finstad 2000). The interview material shows varying will to prioritize these cases in police investigation. Previous police research has demonstrated that domestic violence in general has a rather low status in the police, and that these cases are prioritized differently depending on police unit (Rachlew 2009, Aas 2009, 2014). The theory of “self-fulfilling prophecies” is evident in this context. If police investigators consider domestic violence issues to be “hopeless,” they will consequently find insufficient evidence, and cases are even more likely to be dismissed.

The feeling of whether or not a case is hopeless very much depends on the police’s perception of the victim. Judging the victim’s credibility is central to the police investigation. Thus, we are confronted by some dilemmas and difficulties in assessing family violence according to this penal code provision. Do we face a genuine reciprocity as the informants indicate, or are there underlying power structures that the legal actors have not fully revealed? In an abusive relationship, there may be isolated examples of provocations by the victim, but we should question the relevance of focusing on these when the context has the appearance of a violent regime with a clear distribution of dominance and subordination. In this connection, Judge 6 refers to his experience that some victims provoke their abusive partner in an attempt to end the tension phase and finish waiting for new attacks. If the actions are reviewed in such a context, the considerations of reciprocity and equality become irrelevant. In other words, it is too narrow-minded to examine the victim’s actions without an understanding of the history of the relationship.

In this regard, there are few analytical ideas that have been more central to victimology than that of “the ideal victim.” It was the Norwegian criminologist Christie who originally proposed the concept (Christie, 1986). The ideal victim reflects a person or a category of people who receive total victim status in our culture. No one will blame the victim for the crime. The concept of ideal victims is simultaneously a critique of the common distinction between victims according to external characteristics. However, the police and the legal system face few ideal victims (Aas, 2009), and in this regard, Leer-Salvesen claims that perpetrators and victims rarely exist in pure form in the real world. “Normally our relationship is more complex,” he claims and adds: “We are violated, and we violate during our lives” (Leer-Salvesen, 1998, p. 105).

A regime of violence may often appear composed and blurred to the police. In Finstad’s police research, the police's traditional working logic is directed towards clear actions “which more clearly show who is guilty and innocent (...)” (Finstad 2000, p. 97). Neither is criminal law well adapted to complex problems, but more directed to concrete actions that can clearly be proven in court.

The police role and the value of the investigation

Considering the value of the investigation only in terms of dismissals and prosecutions is too limiting. When the informants are confronted by the question about the high number of dismissals, some police officers underline the importance of preventive measures and treating victims with respect and empathy. Policing has the potential to provide far more value than gathering evidence for prosecutions and convictions. Much victim support may be identified in a good police investigation, where victims are met with empathy and respect, and are carefully listened to (Skodvin, 2000). Although the police cannot be classified as psychotherapists, the potential therapeutic effect of sitting for several hours with an empathetic investigator who understands the victim’s situation and is interested in the details should not be underestimated. Conversations with the police, both in formal hearings and informal dialogues may also have a preventative value. A good dialogue has the capacity to help people to deal with their own thoughts and problems in a different and more active way than if they were left alone with them (Aas, 2017). “To speak is to think,” says Svare, and he adds:

In a dialogue, something more than thinking loudly through your own speech is happening. We are challenged on what we say. We may be asked to answer questions or clarify something that is unclear. And the others’ suggestions may stimulate our own thinking and fill out what we’re thinking, arouse associations or by saying something that we not yet have thought (Svare, 2008, p. 33).

Behind a dismissed case we may find valuable police work. In that case, it is unfortunate for the police that the number of dismissed cases is highlighted as evidence of their failure. Former studies on policing family violence have demonstrated that the police may achieve much in their interdisciplinary networks (Aas, 2009, 2014, 2015, 2017). The interdisciplinary collaboration is necessary both to resolve criminal cases and to provide suitable help for those involved in family violence. In preventive measures against family violence, the police cooperate with a number of actors such as child welfare services, shelters, family reunification offices, social services, the Alternative to Violence organization, incest centers, conflict counseling, victim offices, psychiatric services, hospital emergency departments and other communal services. The police can use their authority to address problems on behalf of their clients and thereby contribute to solutions for both the victims and the perpetrators through these agencies. For their legitimacy and role as problem solvers, it is crucial that the police have different strings to their bow (Aas, 2014).

The interview data has demonstrated that the police feel that they are taking on different roles for the victims. A police officer described herself not only as an investigator but also as a family therapist and psychologist. However, in this connection, the police encounter some dangers and push difficult boundaries. The requirement for objectivity is fundamental in policing and is rooted in both the European Human Rights Convention and Norwegian Criminal Procedure Legislation. As far as possible, information must be collected without the victim’s story being affected by the police (Riksadvokaten, 2015). On the other hand, police investigators occasionally face victims who are unable to convey properly what they have experienced. Then it becomes necessary to approach the victim's story from different angles with open questions that may bring the abuse out of silence. However, the police should distinguish between formal interviews and conversations that are motivated by a desire to help the victim and make her able to understand her situation better. Such a conversation should occur after the formal hearing, so as not to affect the hearing improperly.

The findings in this study indicate that a low proportion of cases from this penal code provision end in criminal sanctions. However, we must raise the question of whether punitive actions are the most valuable outcome of policing family violence.

The legitimacy of criminal sanctions rests mainly on the presumed effect they have on society as a general deterrent. However, we have limited knowledge about both the deterrent and its possible moral effect on the population (Andenæs, 1994). However, on an individual level previous research has shown that victims of abuse had an ambivalent attitude towards criminal cases (Aas, 2014). For some women, the penalty was an important symbolic expression of the wrongs to which they had been exposed. For others, the punishment represented a moral dilemma in their fear of their ex-husbands’ fate. Several of the victims considered the punishment to be necessary to stop the man, at least for a period (Aas, 2014). Other studies have shown that victims of intimate violence do not express a particular need to see their partner or ex-partner punished for crimes that they have committed against them (Lund, 1992; Hoyle, 1998; Grøvdal; 2012).

Conclusions

The research question for the article concerned compliance between government expectations of the penal provisions on repeated and severe domestic violence (i.e. the intention of the law) and police practices concerning these provisions. There is no doubt that the police and the judicial system face major challenges in complying with the intention of the law to capture the overall complexity of abusive relationships. Repetitive and comprehensive interviews of victims are often necessary to understand the history of abuse. The content of the abusive pattern and process seems to be lost in many police investigations. The police have to balance the need to focus on both single events against the totality of abusive relationships. The whole and the parts of a story of abuse are in a mutual and dialectical relationship with each other. This needs to be reflected in police reports.

The police have to draw boundaries between episodic violence and intimate terrorism to decide how to apply these provisions. For this effort, it is insufficient merely to summarize single incidents. An interpretative perspective, from the victims’ point of view, is also necessary. From this perspective, the police may realize that the violence pervades daily life. To apply the provisions, police officers need to look behind stories of individual episodes and dig further. A violent regime may then appear. Psychological violence proves demanding for the police to delineate criminal offenses. Neither the law nor the authorities have defined clearly what is meant by psychological violence. An appropriate approach seems to be to seek actions motivated and articulated by the partner rather than searching for objective actions.

The authorities have an interest in high numbers of prosecutions from the use of any legal provisions. For this penal code, the numbers are disappointing. Dismissed cases are characteristic of the overall situation (more than 70 percent of all cases in 2014 ended in dismissal). Insufficient evidence is by far the most common reason. Repeated abuse in close relationships is especially hard to prove beyond reasonable doubt. Most of these crimes have low transparency. The investigations also suffer from a lack of police resources to investigate these cases properly. However, we should not focus unilaterally on the law enforcement side of the police role. Policing may provide far more value in the struggle against family violence. The police may provide considerable help to the parties in their interdisciplinary network. The police could gain more recognition for this work by documenting what they actually do. In this way it would not just be the number of prosecutions that count.

References

-

Andenæs, J. (1994). Straffen som problem [The punishment as a problem]. Gjøvik. Exil Forlag A/S.

-

Aslaksrud, A. M. & Bødal, K. (1986). Politianmeldt kvinnemishandling: 435 saker anmeldt til Oslo politikammer i 1981, 1983 og 1984 [Abuse of women reported to police] Oslo: Justisdepartementet.

-

Bollingmo, G. C., Wessel, E. O., Eilertsen, D. E. & Magnussen, S. (2008). Credibility of the emotional witness: A study of ratings by police investigators. Psychology, Crime & Law,14(1), 29–40.

-

Bittner, E. (2005). Florence Nightingale in pursuit of Willie Sutton: A theory of the police. In: Newburn, Tim (Ed.) Policing Key Readings. Devon: Willian Publishing.

-

Bjerknes, O. T. & Hoff Johansen, A. K. (2009). Etterforskningsmetoder—en innføring. [Investigation methods—an introduction]. Fagbokforlaget.

-

Bøhm, H. (2003). Menn har ikke monopol på vold [Men do not have a monopoly on violence]. Intervju med menn som har erfaringer fra forhold der kvinnen har utøvd vold. Hovedfagsavhandling i kriminologi. Institutt for kriminologi og rettssosiologi. UiO.

-

Christie, N. (1986). The ideal victim. I E. A. Fattah (Ed.), From Crime Policy to Victim Policy. London: Macmillan.

-

Grøvdal, Y. (2012). En vellykket sak? Kvinner utsatt for mishandling møter strafferettsapparatet. [A successful case? Abused women and their encounters with the criminal system]. Ph.D.-avhandling innlevert ved Institutt for kriminologi og rettssosiologi. UiO.

-

Hellgren, L. Andersson, H. & Burcar, V. (2015). “Du kan ju inte bli slagen av en tjej liksom” – en studie av män som utsatts för våld i nära relationer [“You can’t be beaten by a girl, you know” – a study of men who have been subjected to domestic violence] Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift [p. 82–98]. Vol. 22, nr. 1 (2015) Lunds Universitet

-

Hoyle, C. (1998). Negotiating Domestic Violence: Police, Criminal Justice, and Victims. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

Haaland, T. & Clausen, S. E. (2005). Trusler og maktbruk i parforhold. Utbredelse. I: T. Haaland, S. E. Clausen & B. Schei (Eds.), Vold i parforhold—ulike perspektiver. Resultater fra den første landsdekkende undersøkelsen i Norge [Couple violence—different perspectives]. (NIBR-rapport 2005:3) Oslo: NIBR.

-

Johannessen A., Tufte P.A. & Christoffersen, L. (2015). Introduksjon til samfunnsvitenskapelig metode [Introduction to methods social science]. Abstract forlag. Oslo

-

Johnson, M. P. (1995). Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: Two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 57(2), 283–294.

-

Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet (2014). “Et liv uten vold”: Handlingsplan mot vold i nære relasjoner 2014–2017 [Action plan against violence in close relationships]. Oslo: Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet.

-

Leer-Salvesen, P. (1998). Tilgivelse [Forgiveness]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

-

Lund, V. (1992). Mishandlede kvinners erfaringer med politiet. [Abused women’s experiences with police]. In: Forskningsprogram om kvinnemishandling. Rapport nr. 7. NAVF-rapport. Oslo.

-

Maiuro, R. D. (2001). Preface. Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will also hurt me: Psychological abuse in domestically violent relationships. In K. D. O’Leary & R. D. Maiuro (Eds.), Psychological Abuse in Violent Domestic Relations. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

-

NOU 2003:31. (2003). Retten til et liv uten vold. Menns vold mot kvinner i nære relasjoner. [The right to a life without violence. Men’s violence against women in close relationships]. Justis- og Politidepartementet.

-

O’Leary, K. D. (2001). Psychological abuse: A variable deserving critical attention in domestic violence. In K. D. O’Leary & R. D. Maiuro (Eds.), Psychological Abuse in Violent Domestic Relations. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

-

Pape, H & Stefansen, K (2004). Vold og krenkelser i parforhold. [Violence and violation in relationships] In: Pape, H. & Stefansen, K. (Eds.). Den skjulte volden? Oslo. Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter om vold og traumatisk stress.

-

Rachlew, A. (2009). Justisfeil ved politiets etterforskning – noen eksempler og forskningsbaserte mottiltak [Miscarriage of justice in police investigation]. PhD-avhandling. Det Juridiske fakultetet. UiO.

-

Riksadvokaten (2015). Direktiv om bruk av etterforskningplaner – utvidelse. [Directive on the use of investigation plans]. Riksadvokaten. Oslo.

-

Skants, P. (2014). Omsorg i Kriser: Håndbok i psykososialt støttearbeid. [Care in Crises: Handbook on Psychosocial Support]. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk.

-

Skodvin, A. (2000). Offerets møte med politiet. [Victims’ encounter with police]. In: Skodvin, A. Politi og publikum. PHS forskning 2000:1. Oslo.

-

Straus, M.A. (2008). Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review 30 (2008). 252–275.

-

Svare, H. (2008). Den gode samtalen: Kunsten å skape dialog. [The good conversation. The art of creating dialogue]. Oslo: Pax forlag AS.

-

Sæther, K. E. (2016). Høyesterett og straffeloven 1902 § 219 (mishandling i nære relasjoner). I M. Matningsdal (Red.) Rettsavklaring og rettsutvikling: festskrift til Tore Schei på 70-års dagen. [Supreme Court and Penal Code 1902, Section 219. Abuse in close relationships]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

-

Wadel, C. (1991). Feltarbeid i egen kultur. En innføring i kvalitativt orientert samfunnsforskning. [Fieldwork in your own culture. An introduction to qualitative research]. Flekkefjord: SEEK.

-

Aas, G. (2009). Politiinngrep i familiekonflikter. [Police intervention in family conflicts]. En studie av ordenspolitiets arbeid med familiekonflikter/familievoldssaker i Oslo. Ph.D-avhandling innlevert ved Institutt for kriminologi og rettssosiologi. UiO.

-

Aas, G. (2014). Politiet og familievolden. [Police and family violence]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

-

Aas, G. (2015). Overgrep mot eldre i nære relasjoner og politiets rolle. [Elder abuse in close relationships and the police role]. Oslo: PHS Forskning 2015:4.

-

Aas, G. og Andersen, T. (2017). En evaluering av loven mot mishandling i nære relasjoner. [An evaluation of the law against ill-treatment in close relationships]. Oslo. PHS Forskning 2017: 1.

-

Aas, G. (2017). The Norwegian police and victims of elder abuse in close and familial relationships. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect. Unpublished article.

- 1When this study started, Section 219 was the current provisions. During the project period, the provisions were renamed as Section 282/283 in the revised criminal law of Norway. This article concerns Section 219. However, there are few differences between the new and past criminal law in terms of these provisions. The data in this article have previously been published in Norwegian in the Police University College’s internal report series (Aas and Andersen 2017). This article represents a new composition and systematization of data, as well as some new perspectives. This article uses only some of the data of the whole study. This is the second of two articles based on a study of the policing of the penal provision on residual and severe domestic violence. The original study was based on the Norwegian government’s action plan against violence in close relations for 2014–2017 (Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet, 2014).

- 2Since the adoption of the 1902 Act, the Norwegian Penal Code has had a separate provision governing violations in family relationships, cf. § 219. The provision was completely revised in 2005 (Amendments Act of 21 December 2005 no. 131). The new Penal Code of 2005 contains the corresponding provisions in sections 282 and 283.

- 3BL means “Basis Løsninger” – (“basic solution”)

- 4For training police investigators in Norway, a phase-divided interrogation model has been established. The first phase contains the planning of the interview, the next is about the introduction and establishing contact. In the following phase, the victim is encouraged to make a free and coherent explanation without interruptions. The fourth phase is about questions from the police officer to clarify and elaborate the victim’s explanation. Finally, the officer is supposed to summarize and verify the information before subsequent signatures (Bjerknes and Hoff Johansen 2009).

- 5It turns out that children below the age of 18 years dominate in these situations. Fifty-five percent of psychological violence reported to police involves children under 18 as victims. This mainly involves children who have seen and heard repeated mistreatment of their mother.