The Potential to Become a Good Police Officer

Development of a Competency Framework for the Norwegian Police University College

Organisational Psychologist/Senior advisor, The Norwegian Police University College

Publisert 06.10.2022, Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing 2022/1, side 1-18

The Norwegian Police University College (PHS) needed a common terminology for the evaluation process of applicants’ “required aptness”. This created an opportunity to explore the requirements for the role of student and future police officer through a job analysis.This article describes the process and results of the job analysis conducted in 2011 at PHS. The purpose of the analysis was to create a shared understanding of the concept of required aptness. A set of six competency areas was derived: Interaction, Openness and Inclusion, Integrity, Analytical capacity, Resolve, and Maturity, comprising 13 core competencies. Involving 100 central stakeholders in the organisation and reading of a wide array of central strategic police documents helped create the competency framework, using the analysis of methodological triangulation. The aim of the competency framework was to equip the admission committees with the necessary tools to identify apt applicants and helped them formulate a viable, fair and consistent opinion of an applicant’s potential. This paper includes a discussion of the competency framework in terms of the six competency areas’ practical use, cost and benefit as well as their possible further usability. They have been in use since autumn 2019 to evaluate students throughout their year of field training.

Keywords

- Job analysis

- grid

- methodological triangulation

- competency

- admission committees

- police recruitment.

1. Introduction

Police recruitment and the selection of suitable police officers is widely mentioned in selection and recruitment literature (Lough & Von Treuer, 2013 in Annell et al., 2015; White & Escobar, 2008). This is probably due to the importance of the role of the police officer in maintaining public safety. Good and trustworthy relationships with citizens are of primary importance for the effective execution of police work, particularly in democratic societies where the police force ʻearns’ legitimacy for their actions from the public (Kääriäinen, 2007).

Henson et al. (2010) claim that the selection of quality personnel translates into effective crime fighting, positive community interaction and improved police accountability. On the other hand, potential consequences of selection errors include both social and economic costs. Selecting persons who are ill-suited to the job, given the power and authority police officers possess, can gravely harm the organisation and the trust it holds with the public.

A central question when designing police selection is to define what characteristics the assessment should measure, especially considering the potentially grave implications of selecting ill-suited persons.

A job analysis is necessary in order to describe the content of what organisations define as the desired performance level for its employees. Perlman and Sanchez (2010) define the job analysis for predictor development as an analysis that aims to determine what worker attributes or KSAO (Knowledge, Skills, Ability and Other characteristics) are needed to effectively perform the behaviours defined in the job analysis.

The Norwegian Police University College (Politihøgskolen) (PHS) offers a bachelor’s degree in policing, and applicants must fulfil all admission requirements. The admission requirements (Justis- og Beredskapsdepartementet, 2017) are set by the Ministry of Justice and Public Security and include among other things:

-

Norwegian citizenship

-

Driver’s licence level B

-

Meeting grade requirements in Norwegian language from upper secondary education

-

Achieving general university admissions certification, which means completion of upper-secondary education in Norway

-

Meeting fitness requirements

The next requirement is being evaluated by an admission committee as apt for becoming a student.

A challenge arose when the Academy became a college in the 1990s. Historically, the Police Academy recruited police cadets, who became police colleagues upon their admission to the Academy. In the early 90s, the academy became a university college offering a bachelor’s degree combining academic and practical training. Becoming a university college caused a shift in the overall purpose of admission, concentrating on recruiting students with the goal of their completing a bachelor’s degree before becoming active police officers. This shift between colleagues and students was not sufficiently mirrored in the content of the selection system from 1993 to 2012.

This article describes the process and results of the job analysis conducted at PHS and seeks to examine the use of the derived set of six competency areas which created the framework. The analysis aimed to define the potential applicants may or may not possess to become good students at the College and, ultimately, suitable or apt police officers.

There is only one national police service in Norway, covering all areas of law enforcement. PHS is the only educational institution in Norway authorised to educate police officers and is, thus, the exclusive gateway for all police service in Norway. Police education at PHS is the only higher civilian education in Norway that requires a level of personal attributes (required aptness) to be granted admission.

Aptitude (the natural ability to acquire knowledge or skill) (Wikidiff, n.d.) for police education is used as a criterion in many countries (Aamodt, 2004). The PHS measures more specifically the applicants’ required aptness (the quality of being suitable, suitability), which means that applicants have the necessary personality, mental abilities and attitudes that give them the prerequisites to train to become proficient police officers.

Kurz and Bartram (2008) define competency as various behavioural repertoires that enable (or constrain) the range and quality of a person’s work performance. Their competency model shows that competency develops from a person’s innate potential, which they term “The Disposition Domain”. The model portrays how both innate and learned potential can translate into behaviour. The purpose of the degree program at PHS is to give students who have the required potential the skills they need to develop proficient police behaviours and competencies.

In order to make the admission process fair, transparent and valid, it is essential to have a good operational definition of what competencies “required aptness” consists of. The competencies must be clearly defined and stated (Peeters, 2014) in a way that will allow for measurement of the competencies through methods that provide sufficient reliability and validity (Weiss & Inwald, 2018). However, the complexity of the police officers’ profession (Wilson, 2012) and the many stakeholders in the police organisation make the task difficult.

The Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Police issued the White Paper Number 91 (1983–84): “On the recruitment and education of the police” (Justis- og politidepartementet, 1984). The document explained what it meant to be an “apt” officer for the Norwegian Police by mentioning a few key traits an applicant needed in order to be considered as apt to become a future police officer. Among them:

Communication … ability and desire for social contact. … Temperament (especially attitudes in difficult or seemingly impossible situations or under significant provocation. … Strength of character. … Self-control. . . . (Justis- og politidepartementet, 1984, p.33, translated by the author)

This use of general and somewhat vague and ill-defined terms, without a clear reference to actual police behaviours, gave the selection committees wide room for subjective judgement.

These vague definitions, combined with unstructured 20-minute interviews as well as unstructured and undocumented scoring, did not allow for standardisation of, or transparency in, the admission process. Political emphasis on diverse and broad recruitment to the PHS in recent years could be at risk of biased decisions and low selection validity, as the admission committees had neither clearly defined criteria nor standardised methods to measure by.

De Meijer et al. (2007) looked at the selection of applicants to the Police Academy of the Netherlands and concluded that the evaluation of applicants’ aptness was especially challenging when the applicants had a minority background.

In recognition of these challenges, the author started the work that would determine a set of well-defined operational criteria for use in selecting Norwegian police students.

1.1. The job analysis

The purpose of the analysis was to create a shared language and understanding of the concept of required aptness. The aim of the framework was to equip the admission committees with the necessary tools to identify apt applicants: ones with the potential to complete a three-year bachelor’s degree in police studies and to become proficient police officers in the future.

Peeters (2009) refers to the line of education preceding police work and concludes that a clear “competency approach facilitates the integration of academic understandings and professional needs” (p. 54).

The role of police officer is complex in many aspects (Wilson, 2012). It entails communicating, collaborating and interacting with increasingly diverse communities, which requires broad cultural competencies. In addition, officers must have strong analytical, problem-solving, critical, and strategic thinking, and even technical abilities (Miller, 2008; Raymond et al., 2005; Scrivner, 2006, 2008; Wilson & Grammich, 2009a in Wilson, 2012).

Police roles have evolved in complexity throughout the last decades (Kraska, 2007 in Wilson, 2012). There is little literature defining what competencies and specific personality traits are necessary in candidates who will cope well with this growing complexity in the police role. Peeters (2014) claims that when defining competencies for police performance, the educational institution and the organisation should cooperate closely and create a competency profile that “should refer to the integration of knowledge, abilities and attitudes that are needed to act and behave adequately at work” (Peeters, 2014, p. 91).

Such cooperation at PHS demanded a process where the experienced-based knowledge-how (Ryle, 2015), or tacit knowledge (Polanyi & Sen, 2009) of fellow students as well as police officers became explicit. The idea was to “excavate” the core understanding that generations of police officers had on the nature of the apt colleague and create a common description that could serve as a shared tool of reference. The purpose was to move from an intuitive and unstructured tool for evaluation of applicants to an explicit and defined one. This tool could then become a cornerstone in a more solid and structured method for selecting future students to PHS.

1.2. The Norwegian Police admission process

By 2011, the PHS had four admission committees, each comprised of four members (a police lawyer, two police officers and one representative from another educational institution). The committees worked parallel in selecting 720 new students each year. In 2009 and 2010, structured observations of the committees’ work (Abraham, 2010) revealed a substantial risk for subjective bias and discrimination against the applicants. It also revealed a lack of a common understanding of what required aptness was and how it should be assessed.

As such, it was important for the PHS’ leadership to reach a broad consensus within the organisation on the criteria for a good “generalist officer” (Wilson, 2012).

The conclusions from the 2009–10 observations of the committees prompted the leadership at PHS to commission both a job analysis and, eventually, a new selection process.

To guarantee confidence in the outcome of the new selection process, it was crucial that there was broad understanding and acceptance of the new terminology and the definition of “aptness”. This, in turn, required contributions from many stakeholders among the 12,000 members of the Norwegian police organisation.

The admission committees have judicially-independent and autonomous authority to evaluate applicants. It was, therefore, necessary for the committees to acquire a deep understanding of the definition of the competencies and, later, in the tools that were used to measure them. The first step was to investigate what required aptness meant to the organisation in all its diversity.

2. Methods

During the process of the committees’ evaluation and job analysis, the author cooperated with two psychologists who were hired as external consultants. Together, we gathered data for the job analysis using three stages and four methods – with both qualitive and quantitative elements.

Mixed methods were used in order to utilise a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches (Newman et al., 1998; Tashakkori & Creswell, 2007). This job analysis used a specific type of mixed methods: methodological triangulation, which meant alternating between various methodological approaches to gain several theoretical and methodological “pillars” to support the findings. Risjord et al. (2001) state that qualitative and quantitative methods that are used alternately can contribute to a richer and more detailed knowledge of a phenomenon, while using only one of the methods does not give the same degree of information.

2.1. Stage one: meeting the admission committees

The four admission committees gathered at an annual seminar (November 2010) where the present author and one of the external consultants asked them to pinpoint central criteria that they used to evaluate an applicant’s “required aptness to become police officer”. The same group of committee members participated in stage three of the process, April 2011.

2.2. Stage two: searching in central documents

Political documents are central in defining the police education’s mandate in Norway. It was, thus, important to identify what political leadership had to say about the demands placed on the police and their expectations as to the College’s curricula. Various central strategic and educational policy documents, produced at political, legal and top leadership levels, were central for the job analysis. We searched for documents that yielded descriptions of, and terminology, to describe the required behaviours, competencies and conduct of police officers or police students. The work started with a systematic search of databases in the PHS library for any documents that were relevant to the description of the current and future police student and police officer. With the help of an administrative admission employee at PHS, the search provided some 3,000 pages of these documents, which were included and categorised into relevant terms and concepts.

2.3. Stage three: repertory grid and ranking process with central stakeholders

The grid interview was conducted in pairs. The pairs received a structured description of the interview process before changing pairs and ranking 19 competencies according to their importance (described in detail in 4.3.1). The process was carried out on four groups comprising mostly of police professionals, representing all the stakeholders in the PHS system as well as the Norwegian police force. This gave us a sample of 100 participants: police officers of various formal status in the organisation (leadership to active policing), as well as other stakeholders (civilians working in the police, PHS teachers, admission committees, diversity agents, etc.). In our selection of participants, we aimed to have a diverse group of people in terms of age, gender, and position within the police.

A practical aspect of the process was asking participants to devote 90 minutes of their otherwise scheduled meetings to the job analysis. Three of the meetings gave the opportunity to include many participants who were significant for the process. The fourth meeting represented additional individuals chosen by the author for their diverse roles and points of view. All four meetings where the analysis process was conducted took place during February and March 2011 at PHS in Oslo.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the groups:

| GROUPVARIABLES | STUDENT SUPERVISORS | MIDDLE MANAGEMENT | BLENDED GROUP | ADMISSION COMMITTEES |

| N | 42 | 14 | 18 | 26 |

| Professional background | Senior Police officers with extra education in pedagogical supervision who have the primary contact and supervise the college’s second year students in their field work | Police officers, lawyers, and educational personnel in middle to top managerial levels, who run the education of the college. | Police officers with minority background, recruitment agents from various police districts, diversity agents, sociologists, trade unions and student council. | Senior police officers, police lawyers and educational personnel from other universities who select students for the college. |

| Relevance for the analysis | These officers meet and supervise students over the course of a whole year and see the practicality of their aptness to become police officers | Managers from the four educational units of the college who have a strategic as well as an educational perspective | A broad span of professionals who were invited because of their engagement and significance for the college’s diversity recruitment | Members from the four admission committees who have the mandate to decide who of the applicants have the required aptness to become students and in turn police officers |

| Age | 35–50 | 40–55 | 27–40 | 35–55 |

| Gender | 26 male16 female | 5 male9 female | 10 male8 female | 13 male13 female |

2.4. Participants and data

All participants in the processes volunteered to participate and could withdraw at any time. Only aggregated group data was used and no data on individuals or their statements were recorded. Thus, the study did not require approval from the Norwegian Data Protection Authority.

3. Methodological instruments

The study made use of two methodological instruments:

3.1. Repertory grid

The explorative interview method “Repertory grid” (Kelly, 1955) was selected in order to help participants explore the content of required aptness. In these structured interviews, participants explored comparisons of traits and descriptions of a role (police student) they knew well.

3.2. Shapes competency model

A commonly used method in job analysis in Norway is the use of a standardised personality-based competency model. The participants are asked to prioritise which personal competencies they assess are most important for the required job. This is done in order to assess the relative importance that different stakeholders put on the chosen personal competencies. The shapes competency framework, developed by the psychometric test developer Cut-e (2017) lists 18 general work competencies and is loosely based on the personality model of Kurz and Bartram (2002). In addition to the 18 original competencies in Shapes, we defined and added a 19th competency to the model. Diversity and inclusion were absent from the original Shapes model and was necessary for the analysis. This competency Inclusion was judged to be crucial when trying to measure professionalism within the field of law enforcement and contact with the diverse general public.

4. Procedure

4.1. Stage one: Seminar with the admission committees

The 32 members of the admission committees were gathered (in November 2010) and divided into four groups of eight (their original committees). Each committee took part in a 45-minute group process with the support of the present author and one of the external consultants. Each committee came up with concepts and descriptive terms to define the “required aptness to become police officer” and presented their concepts to the rest of the group.

The session continued with each committee presenting their chosen terms on the wall and every committee member prioritising three of the concepts by marking their top choices. The author ranked 11 of the most central terms, which all agreed had to be a part of the future evaluation of an applicant’s required aptness.

4.2. Stage two: Central strategic documents in the police force’s system

The document analysis was conducted during the months of January to June 2011 and consisted of the careful study of the documents with the purpose of extraction concepts that gave a description of the good police officer or police student as proposed by official policy documents.

The 3,000 pages of documents were systematically searched to collect statements mentioning definitions or descriptions of a good police officer or a good police student. For instance, if a document described that a good police officer should be conscientious, the term conscientious was extracted. The list of adjectives, phrases and concepts became the raw material for the concept analysis (see chapter 5. Data).

4.3. Stage three: Standardised 90-minute process

Prior to the four meetings (described in chapter 2.3), all the 100 participants received a short letter explaining the purpose of the analysis and the form of this step: a 90-minute process with no preparation required.

The process was identical all four times, starting with a random division of each group into pairs. The random division was done to avoid close colleagues being paired together. The pairs started with the Repertory grid interview. After 45 minutes, each group was again sorted into new random pairs to work with the Shapes competency model.

4.3.1. Method A: Repertory grid – explorative interview method

Each member of the sample received six empty, numbered cards and an instruction-and-registration sheet.

Each participant came up with concrete examples of six (anonymous) students they knew, three good students and three less good ones. They wrote down coded names on each of the empty, numbered cards, ranking them from 1 (best student I know) through 2 (next best student I know) and to 6 (least good student I know), until all the cards were filled in. The pairs were instructed to take turns being “interviewee” and “interviewer”.

The interviewees then shuffled their own cards and presented them to the interviewers, who then chose blindly three of the 6 cards. The three cards were then divided so that cards representing better students (numbered 1, 2 or 3) were in one pile and cards representing least good students (numbered 4, 5 or 6) were in the other pile.

Interviewers then asked some set questions about the differences between the best and least good students. The goal was to pinpoint what good students had in common and how the best students were different from the least good students and from each other.

The interviewers were asked to write down the concepts and descriptions that came up. The procedure was repeated three times, then the interviewer and interviewee switched roles, and the process was repeated with the new set of “best and least good student” cards.

The explorative grid interview yielded various triads of concepts. The author collected the papers with the terms and descriptions from each pair before continuing to the next 45 minute stage.

4.3.2. Method B: Shapes competency method – quantitative competency priorities

After completing the grid process in 45 minutes, each group reshuffled into new random pairs. The task here was to prioritise the 19 competencies in the amended Shapes competency model to determine which were most important for the PHS’s required aptness. Each pair received a set of 19 descriptive cards that they needed to prioritise into three categories: Essential, Desirable or Immaterial.

| Competency | Essential | Important | Immaterial |

| Vision & Strategy – develops an ambitious but realistic business vision and translates it into a workable strategy | 1 | 4 | 45 |

| Initiative & Responsibility – acts on own initiative, makes things happen and accepts responsibility for the results | 34 | 11 | 5 |

| Business Development - identifies and seizes commercial opportunities; has a strong positive impact on business growth and profitability | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| Bottom-line focus – focuses on bottom-line results, identifies potential risks and monitors the financial impact of own activities | 1 | 1 | 48 |

| Influence – makes an impact; convinces and persuades others; promotes plans and ideas successfully | 5 | 22 | 23 |

| Networking – builds a useful network of contacts and relationships and utilises it to achieve objectives | 1 | 30 | 19 |

| People management – provides team with a clear sense of direction, inspires and co-ordinates others and keeps them focused on objectives | 1 | 25 | 24 |

| People development – develops people through delegation, empowerment and coaching; promotes career and self-development | 0 | 20 | 30 |

| Inclusion - Behaves in a manner that shows compliance and respect towards people who have different background/ sexual orientation/ gender/ religion/ skin colour then herself | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Organisational awareness – understands the organisation’s informal rules and structures and utilises political processes effectively to get things done | 3 | 23 | 24 |

| Execution – adheres to company rules and procedures; executes plans with commitment and determination; achieves high quality results | 32 | 17 | 1 |

| Systematic approach – uses a methodical and systematic approach; plans ahead, defines clear priorities and allocates resources effectively | 11 | 34 | 5 |

| Steadiness – creates a stable and re-assuring work atmosphere; supports and encourages team in difficult times; is firm and reliable | 32 | 18 | 0 |

| Analysis & Judgement – quickly understands and analyses complex issues and problems; comes up with sound and rational judgments | 30 | 18 | 2 |

| Professional expertise – Demonstrates specialist knowledge and expertise in own area; participates in continuous professional development | 3 | 30 | 17 |

| Innovation – produces fresh and imaginative ideas and solutions; breaks away from tradition; promotes change and novelty | 3 | 31 | 16 |

| Effective communication – communicates in a clear, precise and structured way; speaks with authority and conviction; presents effectively | 34 | 14 | 2 |

| Constructive teamwork - co-operates well with others; shares knowledge, experience and information; supports others in the pursuit of team goals | 46 | 4 | 0 |

| Self-development – aware of own strengths and weaknesses and strives to learn and develop | 40 | 10 | 0 |

5. Data

After all three stages were completed, the author ended up with lists comprising of some 600 terms and descriptions, which varied in their quality and precision across the methods:

Stage one (admission committees’ seminar) yielded 28 terms that were then grouped and prioritised by all committee members into 11 terms. These were mostly adjectives and personality descriptive terms (“social”, “empathic”, etc.).

Stage two (central strategic policy documents) yielded some 140 terms that were mostly future-competency orientated (“Analytic competency”, “Cultural assets”, “Diversity”, etc.).

Stage three (90-minute process with four groups) yielded 400 terms from method 1 (Repertory Grid method) and nine prioritised terms from the 19 competencies in method 2 (The Shapes competency model). The concepts derived from method 1 (Repertory Grid) were similar to the ones derived from stage one (admission committees’ seminar), being mostly adjectives and personality descriptive terms. The 19 concepts in method 2 (Shapes competency model) were well sorted and validated given terms that were formulated in advance by the Shapes competency model.

5.1. Analysis

Starting with the 400 concepts derived from method 1 (Repertory Grid, stage three), we analysed the data. The author systematised the gathering and analysing of the 400 collected terms. The structuring of the qualitative data started by an “open coding” that was grounded in the sample’s broad knowledge of the theme. We then compared the open codes to each other and grouped them into categories (axial coding) (Dourdouma & Mörtl, 2013) that strived to capture the essential meaning of becoming the good police student.

We systematised the various terms according to the number of times they were mentioned. The axial coding enabled us to treat the gathered terms as quantitative data by managing to distil the 400 terms into a matrix of 18, where nine were defined as Essential and nine as Desirable for the execution of the desired activity.

| Essential | Important |

| Good communication | Structured |

| Ability to cooperate | Engaged |

| Positive inclination | Authority |

| Desire to learn | Safe |

| Maturity | Inclusive |

| Knowledge | Self-awareness |

| Empathic | Holistic perspective |

| Reflected | Social |

| Motivated | Analytical |

The process continued by integrating the remaining terms from the various sources into this initial list. We added the prioritised 11 terms from stage one to the 140 terms from the central documents (stage two). Here again, qualitative categorising around clusters yielded eight terms before being processed into the 18 categories that form the axial coding of the Grid method. The same process repeated itself with the eight competencies from method 2, the Shapes competency model, which were defined by the sample as Essential.

| FINAL 13 COMPETENCIES | REPERTORY GRID | SHAPES COMPETENCY MODEL | CENTRAL POLICY DOCUMENTS3. Including process with the admission committees. |

| Initiative and responsibility | Initiative and responsibility | ||

| Inclusion and tolerance | Inclusive | inclusion | Tolerance |

| Structured and systematic | Structured | ||

| Implementation | Implementation | ||

| Cooperation | Ability to cooperate, positive inclination, social | Cooperation | Interaction |

| Safe and stable | Authority, safe | Stable | |

| Empathic | Empathic | Empathy | |

| Cultural understanding and diversity | Cultural understanding and diversity | ||

| Analytical skills | Knowledge, holistic perspective, analytical | Analysis and review | Analytical skills |

| Communication | Good communication | Effective communication | Communication |

| High ethical standard | High ethical standard | ||

| Self-awareness and personal development | Reflected, self-awareness, maturity | Personal development | Maturity, self-awareness |

| Motivation | Desire to learn, motivated, engaged |

In June 2011, the author presented the 13 competencies (see Table 4) to the organisation’s leadership at PHS. The leadership concluded that the 13 competencies were central to the purpose of defining a good student and future police officer.

However, there was concern that 13 competencies were too many for two reasons:

-

Methodology – measuring 13 separate competencies in a selection process that can last one-and-a-half hours at the most was unfeasible in the frame of work that the selection committees had.

-

Communication – communicating 13 different competencies, both internally to the organisation and externally to the public, was not a manageable communicative goal.

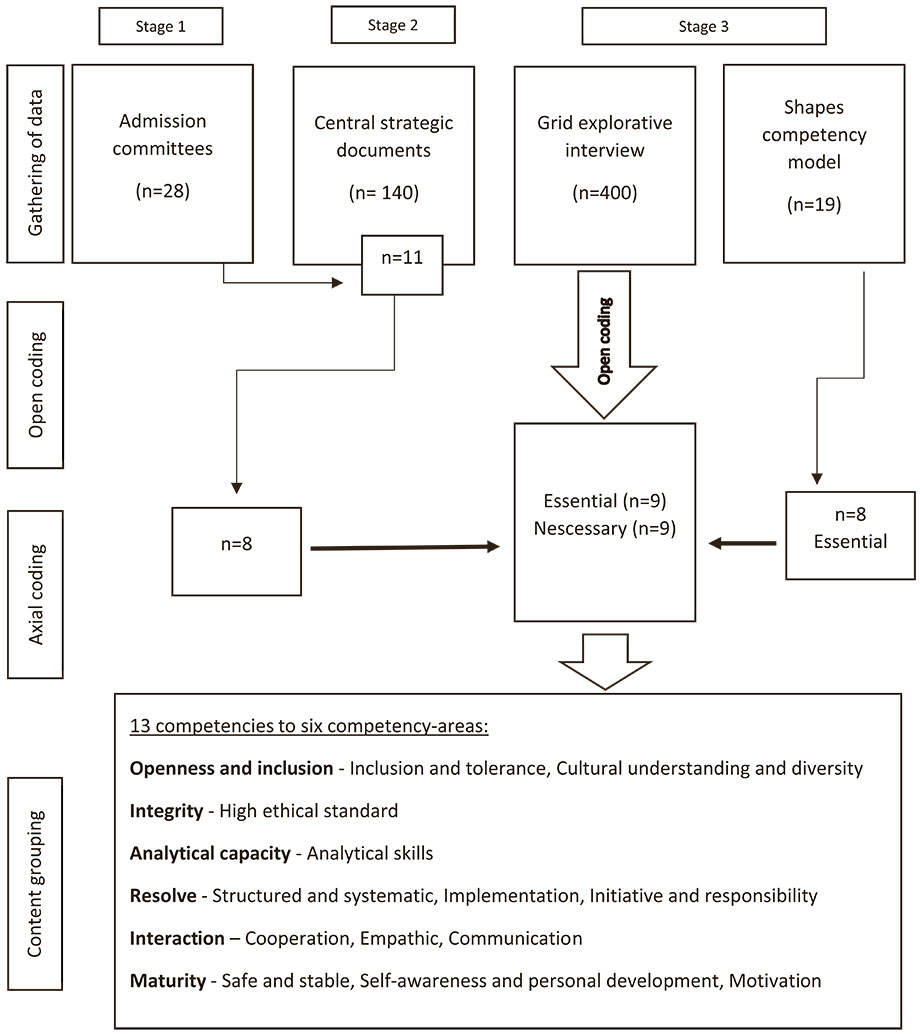

Figure 1

Flow-chart 1 – Extraction of terms

The leadership of PHS requested further reduction of terms. The author regrouped the 13 competencies according to common content, but they remained in their original form as core competencies in six competency areas. A group of five experienced student supervisors (from group 2 in the sample of stage three) formulated operationalised texts for each of the competency areas. The texts were meant to create a common understanding and communication on the underlying 13 core competencies both to the admission committees and to future applicants.

| COMPETENCY AREA | 13 COMPETENCIES | DESCRIPTION |

| Interaction | Empathy; Cooperation; Communication | Cooperates well with others. Is supportive, empathetic, and communicates verbally and in writing in a clear & understandable manner |

| Openness and inclusion | Cultural understanding and diversity; Inclusion and tolerance | Shows curiosity, accommodation and respect towards people who have different background, sexual orientation, gender, religion, or skin colour. Is actively inclusive, explorative and gives everyone equal opportunities. |

| Maturity | Self-aware and self-developed; Motivated; Secure and stable | Is aware of her/his own strength, weakness, and development potential. Shows motivation and engagement and is seeking knowledge. Appears to be secure, trustworthy and shows self-control in demanding situations. |

| Integrity | High ethical standard | Appears to be factual and impartial. Is capable of acting in line with ethical directives. |

| Analytic ability | Analytical skills | Shows learning capabilities and insight in complex situations. Is reflective and makes rational evaluations. |

| Resolve | Structured and systematic; Implementation; Initiative and responsibility | Appears responsible and enterprising. Is structured and systematic in her/his thinking. Makes independent evaluations, shows courage and decisiveness. |

In September 2011, the PHS leadership approved the six competency areas as the content of the term “acquired aptness”, and they were consequently implemented in the selection system.

6. Discussion

We derived a set of six competency areas (comprising of 13 competencies) using methodological triangulation. The process involved data collection from Repertory Grid, a competency model and document analysis. The author used structured and explorative focus group interviews with 100 central stakeholders in the organisation. The purpose was to supply a methodological framework to identify and assess police applicants for the police education. This gave the admission committees a common language and understanding that would support them in formulating a viable, fair and consistent opinion on an applicant’s potential to become an apt police student and eventually proficient police officer in the Norwegian police.

The use of the competency areas created a whole new framework for defining the difference between measuring potential and competency in the organisation. Measuring the applicants’ potential upon admission has historically been isolated from the training itself. The current measuring of the same competency areas during their field training year has given a whole new understanding to the students’ learning and maturing process. Supervisors use the same framework to assess weather second-year students have managed to convert their potential into professional police behaviour.

6.1. The practical use of the competencies

Since 2012, PHS has used the new competency areas for redesigning the information given to potential applicants, including the application website and information given during the application process. In addition, the competencies were central in preparing the admission committees for their work, and they developed a strong ownership of them. The competencies were actively used in training and the practical work of the committees.

Furthermore, PHS changed the conditions for the feedback given to candidates not admitted due to lack of required aptness. Since 2012, rejected candidates have received feedback in terms of where they did not meet standards and how they could improve in these areas. The committees as well as the administration at PHS stated that the consistent use of the competency areas in feedback to applicants simplified the process significantly and contributed to clarity and transparency.

Since 2019, PHS has also applied the competency framework to assess students during their year of supervised training, where they perform actual police service with a supervising officer. Later feedback from the supervisors found the competencies to be a useful framework for assessing students’ aptness, as well as giving feedback to the students about their performance in the field.

The broad use of the six competency areas, both internally in the organisation and towards the public, points to a widespread consensus on their applicability. It is possible that the broad participation of as many as 100 central stakeholders in the job analysis, as well as the ease with which the six areas are communicated, lead to growing familiarity with and acceptance of the concepts and their content.

Our study shows that the admission committees are very loyal to the active use of the 13 core competencies as well as the six competency areas, when evaluating applicants for aptness.

24 of the 36 members of the admission committees are police professionals, who represent the whole police organisation. They help PHS promote the competency-areas “approach” throughout the organisation. The use of the same competency-areas in the evaluation of students in all districts creates growing awareness of the standard for “aptness” throughout the whole organisation – which was one of the main goals of this job analysis.

6.2. Strengths and limitations of the methods

The methods used along the three stages of the analysis proved to yield both different types of concepts as well as different degrees of effort and resources needed to harvest them.

Levine et al. (1980) claim that a varied and mixed job analysis that makes use of more than one procedure/method ensures a solid foundation of documentation and is better than a job analysis that is based solely on one method (for example interviews or merely going through central governing documents). Although we tried to expand the range of data sources to include colleagues and organisational strategists (Perlman & Sanchez, 2010), our participants still consisted mostly of police officers and police leadership. This may have led to a certain degree of social conformity among the participants (Garavan & McGuire, 2001) or to the insertion of outdated competencies reinforced by a police occupational culture (Stanislas, 2014). Involving more stakeholders from the public, or even from other police entities in other countries, could have contributed to an even deeper understanding of the demands future police students and officers will face.

Various stakeholders from the public are the direct recipients of the police service in society. Involving representatives from all walks of life, especially underrepresented groups, in defining which qualities police officers should have could contribute to greater trust in the police service, as well as helping to make the requirements of the role of a police officer more relevant to the needs of the recipients. Despite its importance, PHS did not have the time and resources to conduct such an external survey. Future development of the analysis should involve stakeholders from the public.

6.3. Costs and benefits of job analysis

A frequent objection to conducting a job analysis to identify a competency framework is that it is a time-consuming and financially costly process. This was not entirely true in the case of PHS. Using existing meetings as the source for concept harvesting reduced the cost of organising and funding large gatherings. Recent developments in online meeting technology might make it more efficient to involve bigger and more diverse groups of contributors if the process was adjusted to the digital world’s limitations.

PHS paid for 70 consultant hours. In addition, two employees used an accumulated period of about three weeks of full-time work. While these costs were by no means insignificant, they provided good value for the organisation by creating a new standard for admission fairness and transparency, an assessment structure, and a framework for a common understanding of what is required of the apt applicant.

6.4. Further development

The author sees the importance of revisiting the job analysis in order to control the relevance of the competencies for the education of a police officer and the future role they will fill. Development in the current demand of the police role, as well as societal and even political changes, will also play a role in determining the evolution of the definition of the competencies. The terror attack of 22 July 2011 in Norway, the migration wave of 2015 in Europe and the ongoing terrorist attacks in the world are some examples of such changes. A dynamic understanding of the role of police students and future police officers can pave the way to future skills and competencies that will become necessary and relevant. Including new and relevant skills that are closely connected to the police’s ability to perform its role in a constantly changing and more diverse society is a measure of the future relevance of the framework.

Since 2019, the students have also been graded by trained supervisors on their conduct and aptness during their B2 (field training) year, using the same six competency areas. This underscores the relevance and applicability of the job analysis, as the use of a common language for assessment, throughout the three years of education, contributes to consistency in the evaluation. The competency areas are currently used both to evaluate students’ potential prior to admission and again for the evaluation of the students’ actual behaviour as an indicator of their development of the desired competencies during their field training.

The use of the same competencies in such a real-world setting can help the competency model stay relevant and useful in the future. This can also provide opportunities to validate the admission process.

The Norwegian model, which encompasses the creation of a clear competency framework that stems from the police organisation’s needs for its future force and is closely connected both to the selection process of apt police students and the police education, can hopefully be relevant to other police forces as a corner stone in building up their future force with the suitable personnel.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the leadership of the Norwegian Police University College (PHS). The author wishes to thank our colleagues from the Norwegian National Police Force and all the other participants in the job-analysis who provided insight and expertise that greatly assisted the final product PHS currently uses. I thank organisational psychologists Espen Skorstad and Einar Wergeland Jenssen for their contributions and support. I am grateful for my supervisor Dr. Magnus Odeen’s patience, feedback and support throughout the writing process.

List of central strategic documents for the harvesting of terms (January – June 2011):

-

Official Norwegian reports – The Police Role in Society, (Analysis part 1, 1981; Analysis part 2, 1987) (NOU Politiets rolle i samfunnet delutredning 1, 1981; delutredning 2, 1987)

-

Planning Police Staffing – The Police Towards 2020 (Bemanningsprosjektet – Politiet mot 2020) (POD, 2008)

-

Strategic Competency Management (Strategisk kompetansestyring (POD, 2011)

-

Strategic Plan for The Norwegian Police University College (Strategisk plan for PHS, 2009)

-

Personnel Policy for the Norwegian Police (Overordnet personalpolitikk (POD, 2008-2013)

-

Regulations for Moral Suitability (terms used during B2 supervised year) (Forskrift om skikkethetsvurdering, 2005)

-

Assessment of Aptness during B2 supervised year (internal documents 2006-2001)

-

Admission Regulations for the Bachelors’ degree at the Norwegian University College, 2008 (Regler om opptak til Bachelorutdanningen ved Politihøgskolen, 2008)

-

New Communication and Recruitment Material for the PHS – 2011

-

Educational Framework for the Bachelor Education at PHS (Rammeplan for bachelor, 2011)

-

RevisedCcurricula (Reviderte fagplaner, 2011)

-

White Paper Number 22 – the police reform (Stortingsmelding nr. 22 – Politireformen POD, 2000-2001)

-

The Police Act (Lov om politiet, 1995)

-

Police Directives (Politiinstruksen, 1990)

-

Strategic Analysis, Strategic Plan – input to the revision of plan (mai 2011)

The list is not exhaustive. We skimmed through some additional documents in order to see if they can add new terms and these were not mentioned when their contribution was similar to other documents.

References

-

Abraham, S.(2010).

Evaluation of the admission committees 2009, 2010

. Unpublished Power Point presentation. -

Annell, S.,Lindfors, P., &Sverke, M.(2015). Police selection – implications during training and early career.

Policing: An International Journal

, 38(2), 221-238. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-11-2014-0119 -

Cut-e. (2017).

Testdokumentasjon – Shapes (basic)

. https://cut-e.app.box.com/v/dokumentasjon/file/13268573136 -

De Meijer, L. A. L.,Ph. Born, M.,Van Zielst, J., &Van Der Molen, H. T.(2007). Analyzing Judgments of Ethnically Diverse Applicants During Personnel Selection: A study at the Dutch police.

International Journal of Selection and Assessment

, 15(2), 139-152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2007.00376.x -

Dourdouma, A., &Mörtl, K.(2013). The Creative Journey of Grounded Theory Analysis: A Guide to its Principles and Applications.

Research in Psychotherapy

, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.4081/ripppo.2012.108 -

Garavan, T., &McGuire, D.(2001). Competencies and workplace learning: some reflections on the rhetoric and the reality.

Journal of Workplace Learning

, 13(4), 144-164. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620110391097 -

Henson, B.,Reyns, B. W.,Klahm Iv, C. F., &Frank, J.(2010). Do Good Recruits Make Good Cops? Problems Predicting and Measuring Academy and Street-Level Success [Article].

Police Quarterly

, 13(1), 5-26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611109357320 -

Forskrift om opptak til bachelorutdanningen ved Politihøgskolen, (2017). https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2017-08-29-1592

-

Justis- og politidepartementet. (1984).

Om politiets rekruttering og utdanning [On the recruitment and education of the police]

. (St. meld. nr. 91 ).Oslo

:Justice and police department

-

Kelly, G. A.(1955).

The psychology of personal constructs : 1 : A theory of personality (Vol. 1)

.Norton

. -

Kurz, R., &Bartram, D.(2002). Competency and individual performance: Modelling the world of work.

Organisational effectiveness: The role of Psychology

.Wiley

. Pp. 227-258. -

Kurz, R., &Bartram, D.(2008). Competency and Individual Performance: Modelling the World of Work. InI. Robertson,M. Callinan, &D. Bartram(Eds.),

Organizational Effectiveness: The Role of Psychology

(pp. 227-255).Wiley

. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470696736.ch10 -

Kääriäinen, J. T.(2007). Trust in the Police in 16 European Countries:A Multilevel Analysis.

European Journal of Criminology

, 4(4), 409-435. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370807080720 -

Levine, E.,Ash, R., &Bennett, N.(1980). Exploratory Comparative Study of Four Job Analysis Methods.

Journal of Applied Psychology

, 65(5), 524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.65.5.524 -

Newman, I.,Benz, C. R., &Ridenour, C. S.(1998).

Qualitative-quantitative research methodology: Exploring the interactive continuum

.SIU Press

. -

Peeters, H.(2009). Ten Ways to Blend Academic Learning within Professional Police Training.

Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice

, 4(1), 47-55. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pap017 -

Peeters, H.(2014). Constructing comparative competency profiles. InP. Stanislas(Ed.),

International perspectives on police education and training

(pp. 90-113).Routledge

. -

Perlman, K., &Sanchez, J. I.(2010). Work Analysis. InJ. L. Farr&N. T. Tippins(Eds.),

Handbook of employee selection

(pp. 73-98).Routledge

. -

Polanyi, M., &Sen, A.(2009).

The tacit dimension

.University of Chicago Press

. -

Risjord, M.,Moloney, M., &Dunbar, S.(2001). Methodological Triangulation in Nursing Research.

Philosophy of the Social Sciences

, 31(1), 40-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/004839310103100103 -

Ryle, G.(2015). I.—Knowing How and Knowing that: The Presidential Address.

Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society

, 46(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1093/aristotelian/46.1.1 -

Stanislas, P.(2014). Introduction: Police education and training in context. InP. Stanislas(Ed.),

International perspectives on police education and training

(pp. 1-20).Routledge

. -

Tashakkori, A., &Creswell, J. W.(2007). Editorial: The New Era of Mixed Methods.

Journal of Mixed Methods Research

, 1(1), 3-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906293042 -

Weiss, P. A., &Inwald, R.(2018). A Brief History of Personality Assessment in Police Psychology: 1916–2008 [journal article].

Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology

, 33(3), 189-200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-018-9272-2 -

White, M. D., &Escobar, G.(2008). Making good cops in the twenty-first century: Emerging issues for the effective recruitment, selection and training of police in the United States and abroad [Article].

International Review of Law

, Computers & Technology, 22(1/2), 119-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600860801925045 -

Wikidiff. (n. d.).

Aptness vs Aptitude – What’s the difference?

Retrieved 05.08.2019 from https://wikidiff.com/aptness/aptitude -

Wilson, J. M.(2012). Articulating the dynamic police staffing challenge: An examination of supply and demand.

Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management

, 35(2), 327-355. -

Aamodt, M. G.(2004).

Research in law enforcement selection

.Universal-Publishers

.