Motivating Police Reform Through Multimodal Sensegiving

How Change Was Promoted Through Videos in the Swedish Police Reorganisation

PhD Candidate, Umeå School of Business and Economics, Umeå University, Sweden

Corresponding author

Associate Professor, Department of Education, Umeå University, Sweden

Publisert 28.03.2022, Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing 2022/1, side 1-18

In this paper, we contribute to understanding of how video films were used by change management as a communication strategy to portray and promote the organisational reform of the Swedish police in 2015. Based on a multimodal analysis of 44 video films, we theorise how the Swedish police change management “gave sense” to the transformation and future state of the police service. The findings show how change was motivated through descriptions of contexts, the problematisation of the present situation, prescriptions of the change process, and forecasts of an ideal future status for the Swedish police. These messages were reinforced visually using stereotypical images and by layering multiple modes of communication. The paper contributes to the literature on organisational change and police reform by describing how change can be motivated and legitimised through persuasive portrayals of the present and the future. We conclude that multimodal communication through video is a powerful technique for sensegiving, with the potential to construct credible, but not necessarily accurate, accounts of organisational change.

Keywords

- Police reform

- reorganisation

- sensegiving

- multimodality

- video

1. Introduction

In this article, we analyse how the Swedish Police reform in 2015 was portrayed and communicated internally in the police to promote organisational change. We do this by analysis of a series of videos that were disseminated internally in the police organisation at the time. The videos were a central aspect of the communication strategy of the police, and they were developed by initiative of a central ‘change management implementation committee’. As such, the material provides opportunities to analyse central ideas pertaining to the reorganisation of the police, as well as how organisational change was planned to take place.

The reform of the Swedish police was extensive, involving some 28,000 employees (Björk, 2018), and it had far-reaching economic, organisational, and geographical consequences in an agency with pronounced societal importance (Police Organising Committee, 2012). Although the reform has been examined in the Nordic scholarly community from various perspectives (c.f. Cameron, 2017; Granér, 2017; Wennström, 2014), less focus has been directed to how the organisational change was initiated and promoted internally by the change management. During the reorganisation, communication was considered a central aspect of a successful change implementation, and the ambition was to involve as many employees as possible in the process. To initiate change, a central Implementation Committee was established, and this committee in turn engaged several organisational consultants for support (see Official Reports of the Swedish Government, 2015; Granér, 2017). What makes the communication effort in this case unique is that key ideas relating to the change were captured and communicated in 44 video films. These were part of the change communication strategy with an aim to create a broad understanding of the need to form one coherent Police Authority. The production of the films was outsourced to an external production company with the change committee as a client, and the videos portrayed the future direction of the new authority. The committee itself refers to these videos as “campaign-like” films (four minutes in length on average) that were used as discussion material and produced to facilitate motivation, participation and insight into the change and the implementation process (Official Reports of the Swedish Government, 2015). According to the “Final Report of the Implementation Committee” (2015, p. 15) the target groups of the videos were police employees and managers and the rationale behind the production was to provide direction due to a perceived lack in the capacity in the organisation to “drive change”.

Through analysis of these films, and with “organisational sensegiving” as a theoretical frame (c.f. Gioia & Chittipeddi, 1991), the aim of this article is to examine how the Swedish police reform was communicated internally in the organisation through means of visual media. Whilst the material does not allow for an analysis of the outcomes or impact of change communication on organisational members, the video material provides opportunities to analyse the central ideas that motivated change, as well as how the reorganisation was planned to take place. With this focus, the study adds an organisational change perspective to previous research on police reform that mainly has described the change from institutional perspectives and at a policy level (see Cameron, 2017; Wennström, 2014). It also complements public evaluations of the reform that mainly have targeted how the change was experienced by police employees and key stakeholders (see the Swedish Agency for Public Management, 2016, 2017, 2018).

To provide a theoretical lens and to analyse how the reform of the police was promoted internally, we draw on research on sensegiving of organisational change. The concept of sensegiving stems from empirical research on change management. It originally described how leaders try to influence others’ perception of organisational reality during change (Gioia & Chittipeddi, 1991). Since the establishment of the concept, much of the research on sensegiving has focused on how various actors and groups attempt to influence how change unfolds (Kraft et al., 2015). As video material entails a “fusion of image, sound and movement” (Toraldo et al., 2016, p. 439), it provides ample opportunities to examine how different semiotic modes such as imagery, actors, speech, space, and embodiment are important in sensegiving efforts to construct representations of planned organisational change (Höllerer et al., 2018; Toraldo et al., 2016).

1.1 The Swedish police reform

The Swedish police reform of 2015 entailed a change in which 21 local police authorities were merged into one police organisation with seven police regions and national departments for support and monitoring. As pointed out by Cameron (2017), the change was based on the results of a parliamentary committee and motivated by an unclear division of responsibilities between national and local levels of the police. Although the change has been described as a far-reaching centralisation of the Swedish police, it also aimed to increase heterogeneity at the local level (Björk, 2018). Lindberg et al. (2017) discussed this dual objective in terms of a paradoxical tension that surfaced throughout the organisation in the period immediately after the change.

Regarding how the change was implemented within the police, Björk (2016, 2018) described the reform as a top-down process characterised by a narrow focus on coherence and hierarchy. Björk (2018) consider that the organisation was impacted by a “rationalistic reform culture” (p. 1) characterised by centralisation and “romantic expectations of the future” (p. 3) state of the organisation. Similarly, Holgersson (2017) claimed that hopes for a more rational future organisation were the main motive behind the change. Wennström (2014) and Granér and Kronkvist (2016) criticised the reorganisation, arguing that it was overly technocratic and implemented by reformers with little regard for the specifics that characterise policing. This critique was also put forth by Granér (2017) who in a discussion about the ideas behind the reorganisation claimed that it was based on mainstream management theory rather than knowledge about the particularities of police work.

Since the implementation of the reform, several public evaluations have been conducted (see The Swedish Agency for Public Management, 2016, 2017, 2018). Whilst these reports do not assess the long-term outcomes of the change, a general conclusion about the change management was that the complexity of the reform was underestimated at the time, something that for instance was evidenced in a narrow time-plan. As regards the internal communication of the reorganisation, the evaluation reports conclude that this was a key aspect and prioritised dimension of the change effort. For example, an Implementation Committee was established, and this committee worked extensively with various forms of internal communication referred to as “change communication” (i.e., video-films, websites, posters, seminars) to build confidence in the reform (The Swedish Agency for Public Management, 2016). According to the final evaluation of the reform (The Swedish agency for public management, 2018), these efforts had an impact on the change, as the quality of the internal communication about the reform work was reported to decrease significantly when the formal implementation of the new organisational structure was completed. This deterioration coincides with the closure of the Implementation Committee that among other communication outlets also managed the aforementioned video production.

While much research describes the reform largely as a top-down project, some studies highlight that several goals of the reform have been described as focusing increasingly on the local. For example, Kihlberg and Lindberg (2020) analysed how top managers within one police region adapted to the change by actively contributing to shaping the new management philosophy in which the empowerment of individuals in lower tiers was given a central role.

These evaluations and previous research on the Swedish reform indicate several similarities between the implementation of the Swedish reforms and those in other Nordic and European police departments. For example, in a study of police reform in Denmark, Degnegaard (2010) described the implementation as technocratic and dependent on external experts. This line of reasoning is also evident in a study by Fyfe & Richardson (2018) on police reform in Scotland. The authors described how a key dimension of the initiation of the reform entailed the legitimisation of change by external experts who provided information and guidance about the change.

In summary, a common theme in the literature on Nordic police reforms is the description of a division between change management (i.e., reformers and consultants) and representatives of everyday policing. In this divide, the everyday work practice of rank-and-file officers is often described as the target of change. However, as recipients of change the police officers are usually excluded from decision-making and change implementation (Fyfe et al., 2018). Furthermore, because the implementation of change is primarily an administrative task, the literature on police reform describes how the key elements of change initiation are the use of experts to legitimise change and the promotion of an ideal future state of the organisation. This approach promotes change through arguments of increased efficiency, uniformity, and rationally organised functions. In this paper, we describe and theorise how these themes in the literature on police reform can be understood as central aspects of strategic change communication – here conceptualised as organisational sensegiving during change.

1.2 Sensegiving and organisational change

As stated by Chan (2007), police reforms involve sensemaking as change brings uncertainties and disruptions that organisations need to process and ascribe meaning to. Reforms are also occasions for sensegiving, which denotes the “process of attempting to influence the sensemaking and meaning construction of others toward a preferred redefinition of organizational reality” (Gioia & Chittipeddi, 1991, p. 442). Gioia and Chittipeddi’s seminal article on sensegiving shows how various strategies of sensegiving and sensemaking are central in different phases of planned organisational change. In the early stages of change, management tends to focus on envisioning – that is, making sense of and describing the strategic vision for the organisation. After initial envisioning, there is usually a phase of signalling change, in which the status quo of the organisation is questioned and the current stable way of doing things is disrupted. Following signalling, a phase of re-visioning in which stakeholders respond to the signalled vision and in which resistance to change is addressed. Lastly, energising describes how an emergent commitment to change is solidified and communicated widely by change management.

The sensegiving concept has previously been used to describe the role of leaders and change management during strategic organisational change. For example, Kihlberg and Lindberg (2020) in a study of change within the Swedish police service analysed how managers utilise reflexivity in sensegiving to facilitate participants’ sensemaking. Moreover, this type of influence can be exerted through various modes of social interaction (Virkkula-Raisanen, 2010), such as written communication and situated interactions, as well as metaphors (Cornelissen et al., 2012) and symbols drawn from varying contexts (Rouleau & Balogun, 2011). For example, Guiette and Vandenbempt (2016) showed how a poster that displayed information about a change initiative was a “crucial materialisation of the change process” (p. 69). The poster provided sense by unpacking the studied change and making it comprehensible for others.

The sensegiving framework on change that we present in this paper will help analyse how organisational change is framed during the reorganisation of the police. Sensegiving builds on the fundamental notion that for strategically initiated change to happen, members of an organisation need to be influenced. An analysis based on sensegiving investigates the signifiers drawn upon to destabilise the status quo and promote change. This article explores how visual media was mobilised for the Swedish police reform to justify and explain the organisational change. This approach offers the possibility to examine how visual material aimed at promoting change draws on several modes of communication (i.e., visual, material, and verbal) to communicate meaning. Thus, an analysis of visual materials presents the possibility of theorising how ideas are promoted in a multimodal fashion, as videos allow several modes of communication (Höllerer et al., 2018). Additionally, the approach provides a useful heuristic to study and discuss how some issues within the video material are given more emphasis than others and how the discourse about change in large was shaped.

2. Method

As mentioned, the analysis involved 44 videos produced as part of a change-management strategy to create an understanding of the necessity of unifying the Swedish police service (Police Organising Committee, 2012). The videos, issued between March 2013 and January 2015, were used internally and externally to communicate change. In overview, the material has similarities with the genre-specific aspects of documentary films, with features such as voiceover narration; mise-en-scène observations, with speech overheard or fly-on-the-wall characteristics; interviews; and title-screens showing animations, organisational charts, pictures, and text in between scenes (Nichols, 2001). As noted by Nichols (2001), this type of evidentiary editing is customary when the audience is expected to understand the visual imagery as evidence rather than atmospherics or rhetoric. The videos were professionally developed by a production company and the project was requested by the implementation committee as part of the “change communication” strategy (Official Reports of the Swedish Government, 2015). Based on verbal communication with a representative of this production company, an inspiration in the production of the videos was the change management ideas of John Kotter (2002; 2012). This in turns means that the videos among other things aimed to construct a compelling vision of the future state of the police, and in addition communicate this to increase buy-in and overcome distrust and ambiguity.

2.1 Analysis

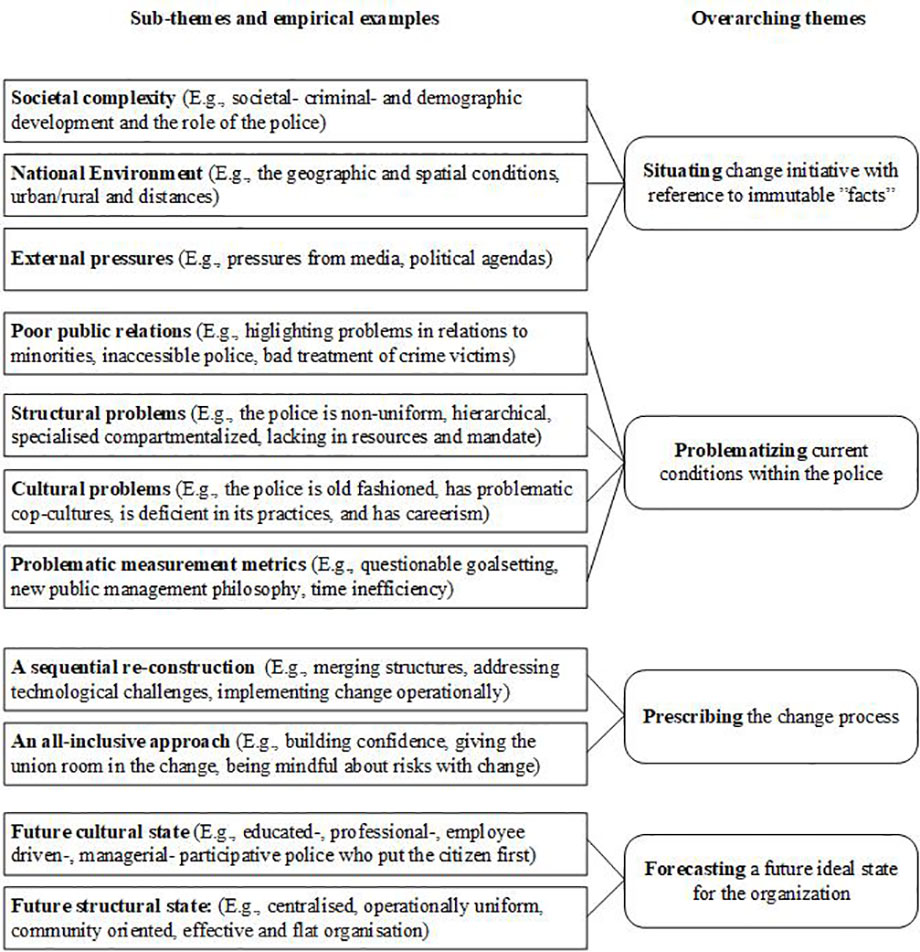

The material was analysed in an abductive manner (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2007) in three phases. First, a content analysis of the material was performed to map themes associated with the change. In this phase, data-driven coding of the videos’ content was undertaken to identify what the films were about in terms of topics. The content analysis was aided by the software Nvivo 11 (Nvivo 11 Pro, 2015) and generated 724 descriptive codes that were arranged in a tree structure with two levels of subthemes and one level of overarching themes, which we refer to as sensegiving themes. With inspiration from Gioia et al. (2012), we illustrate these findings through a code structure in Figure 1 in the findings section. This analytical phase gave insights into the main concerns associated with the change initiative and how the films addressed these topics.

In the second phase, themes from phase one were reanalysed in terms of how the material was mobilised to communicate meaning within each theme. This involved the analysis shifting from a focus on what the films were about to how communication was conducted. To facilitate this analysis, the theoretical concept of semiotic modes guided the coding. Semiotic modes are theoretical constructs, such as actors or space, used to group communicative resources (Leeuwen, 2005). So, for example, a film sequence with a specific person (i.e., a top manager or civilian) accompanied by a specific local setting (i.e., a lecture hall or a suburb) could be said to draw on the semiotic modes of actors and spaces to reinforce the message of the sequence. Following Iedema (2003), and Maier (2014) we reviewed the material using five semiotic modes as analytic lenses and pre-set categories with which we analysed how the video material was mobilised to portray the organisational change initiative. These modes were actors, speech, spaces, embodiment, and imagery. In Table 1, these modes are exemplified:

| Semiotic mode | Examples |

| Actor | Gender, age, ethnicity, position |

| Speech | Dialogue, monologue, pro-/contra- arguments |

| Space | Workshops, meetings, public, organisational |

| Embodiment | Gestures, body-language, actions |

| Imagery | Objects and tools such as charts, maps, uniforms, vehicles |

In the analytical phase, the video annotation software ELAN (2017) aided the identification of semiotic resources, the categorisation of resources into modes, and the association of modes with sensegiving themes from the content analysis. By linking modes to the manifested sensegiving activities within each theme, our analysis targeted how multiple modes were organised to mobilise meaning and illuminate various aspects of organisational change.

3. Findings

Four emergent themes of change were constructed based on the content analysis: (1) situating, regarding issues related to the recognised context of the change; (2) problematising, relating to obstacles and difficulties within the current organisation; (3) prescribing, involving topics related to the change process; and (4) forecasting, relating to predictions about a future ideal state for the organisation. We conceptualised these constructs as sensegiving themes, consisting of issues and main concerns communicated through the videos. Figure 1 summarises the content within the respective themes.

Figure 1

Data structure subthemes and emerging sensegiving themes

As shown in Figure 1, the overarching themes we constructed indicate either important domains by which change is framed, related to processes of organisational change, or different states of the organisation. For the second part of the analysis, we constructed a cross-tabulation to overview how the material within each theme was mobilised to communicate meaning (see Appendix 1). Below, we describe each theme in-depth and show how multiple semiotic resources and modes were mobilised when communicating the themes.

3.1 Situating

This theme reflects how the institutional context was described in terms of immutable “facts” justifying the necessity for organisational change. For example, increasing societal complexity resulting from evolving crime patterns, globalisation, or increased digitalisation, was regularly referenced as a type of ongoing societal development that made change necessary for the police and could affect where their focus should lie. External pressures were also referenced as facts relevant to police activity. These pressures were described in terms of a changing media landscape and political steering of the police. The national environment – specifically, the geography of Sweden, and the great distances between major settlements – was also invoked to convey the message that changing the police service was necessary to meet contemporary demands. One example of this reasoning was when a top management representative within the police made the following comment in one of the videos:

PM (Police manager): We have a changing society; there is no doubt about it. People will not testify; we can’t work with leads in our cases as we used to, society is more mobile nowadays, and with this, we have to work more efficiently (Video 22, 00:02:27-00:03:02).

The excerpt exemplifies that this sensegiving theme is about offering “facts” to describe the institutional environment. These facts were promoted in the film material in neutral terms and as features of contemporary society that lie beyond the influence of the police, thereby substantiating the message that the organisation must change in order to adapt.

There were two recurring tendencies when mobilising semiotic resources and modes within the situating theme. First, authority figures were paramount in the communication of why change was a necessity. The notion of authorities in this regard invoked objective status and the legitimacy of change. Figures of authority were personified through representatives of top management and external expertise (professors and researchers) who gave verbal statements that informed the viewer about society, the police, and predictions about the nature of policing and crime. To communicate these facts, moving images portrayed authority figures mainly in interview settings. There were also graphics of statistics – about crime rates, for example – to substantiate the claims made. Together, the authority figures embodied the seriousness and credibility of the message that change is necessary.

The second tendency was to combine the authorities mentioned above with moving images of ongoing, uniformed policing (see Figure 2 for an example). Statements from the authority figures were corroborated by imagery from police practice, such as police patrol vehicles, radio communication, and uniforms placed in the foreground. Furthermore, regarding space, various semiotic resources were operating when displaying police work favouring external (night-time) locations such as streets and squares visited by police.

This combination of verbal statements about policing and non-verbal communication and images of policing “as it happens” is an example of linkage between multiple modal resources. The portrayal of managers and researchers (mostly older males) as those possessing the facts about the contextual environment was strengthened by imagery and locations demonstrating the practical reality of Swedish police. Together, these modes constitute credible claims about the true nature of things.

3.2 Problematising

Another topic in the videos was the problematisation of the status quo within the police organisation. This issue was revealed by highlighting various weaknesses that plagued the police service before the planned change. In this regard, the concept of problematising is similar to the notion of signalling (Gioia & Chittipeddi, 1991) or sensebreaking – a process in which organisational strategies are symbolically destroyed and given a negative meaning during the initial stages of strategic change (Pratt, 2000). In our case study, several problems in the current organisation were about poor public relations, such as aloofness and difficulties dealing with minorities and victims of crime. Furthermore, the structural disposition of the current police organisation was criticised for being too compartmentalised, hierarchal, specialised, centralised, non-uniform, and generally inefficient in its operations. Cultural problems were frequently highlighted, including the fact that the police were old fashioned and therefore operationally deficient, and were part of a problematic cop-culture that could translate into internal careerism for managers. Such claims were made by police officers and individuals outside the police organisation alike. For example, one top manager asserted that the current police service was afflicted with internal territorial claims and prestige, “both amongst local police authorities but even more on the national level” (quote from video 19). Related to these aspects were problematic measurement metrics such as inadequate goalsetting and deeply entrenched new public management (NPM) ideas. In the Swedish context, this was discussed extensively in terms of the “hunt for numbers” [pinnjakt, author’s translation] that prevailed before the reorganisation, meaning that investigations of simple crimes were used as a means of improving crime-statistics, despite lack of evidence that such efforts have a significant effect on crime prevention and law enforcement in general.

Regarding the mobilisation of semiotic and modal resources, one pattern in the problematising sensegiving theme was the plurality of voices expressing problems. Sources of accusation included interview-prompted monologues wherein normative criticism was directed towards the police, mainly from actors in outdoor spaces. The interviewees included youths from immigrant backgrounds commenting on policing in deprived locations, concerned parents, senior citizens, police officers describing internal cultural problems, and victims of crime commenting on various shortcomings in the police such as lack of efficiency and poor service. These criticisms were accompanied by serious facial expressions and tense body language (embodiment) and were interpreted and nuanced via external experts and objects such as reports, surveys, and empirical evidence. Vivid examples of imagery that illustrate this include man-on-the-street (MOS) interviews reinforcing a message, symbolic images of bundles of reports slammed onto a table, and a large pile of documents from a survey signalling overwhelming evidence of the seriousness of a situation. In all, the imagery regarding this theme is characterised by a plurality of sources of criticism.

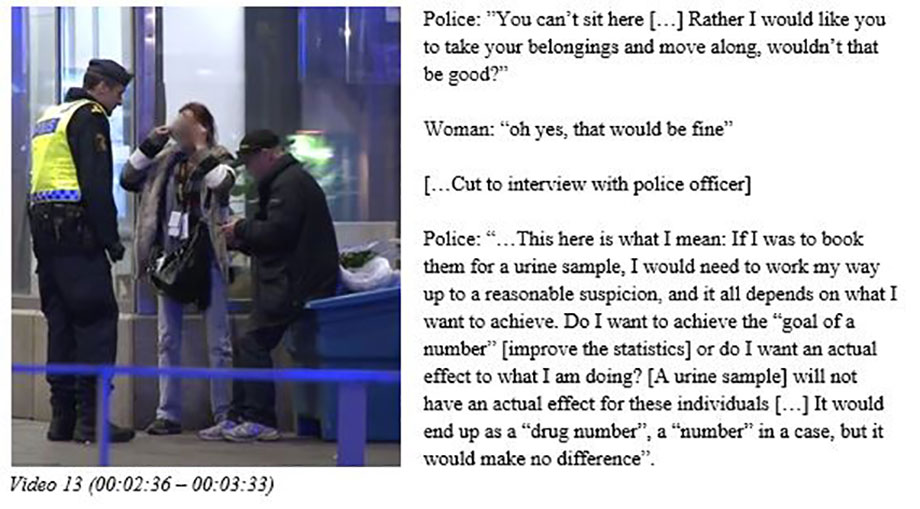

In addition to a compilation of voiced concerns and statements, the video material presented problems more directly by visualising how practices associated with the old organisation created difficulties for the police. One such example was a video sequence that showed a police officer making two drug addicts leave a street rather than arresting them. The objective was to illustrate a problem of performance indicators related to the issue of NPM:

Figure 2

Visualising police performance

In the example above, modal resources associated with police practice (the street, social problems) provide insight into the realities of policing. The police officer’s actions exemplify a new practice, while the symbol of a urine test illustrates a performance measure. Hence, problematic conditions are illuminated using examples of real-life situations.

Our interpretation of the problematising sensegiving theme is that multiple modes are combined in ways that constitute common organisational and societal stereotypes of victims. For example, victims of crime were repeatedly represented by elderly or female individuals describing their vulnerability in exposed places, while victims of unjust policing tended to be teenagers in deprived neighbourhoods explaining the reasons behind their distrust of the police. Additionally, victims of the police sector’s internal culture were portrayed by officers in uniform expressing how internal behaviour and boundaries hindered their professional practice. The stereotypes reinforce a notion of reality characterised by individual and social vulnerability as well as organisational dysfunctionality.

3.3 Prescribing

The prescribing theme consists of sensegiving activities concerning the strategic change itself. Hence, this theme is constructed from present- and future-oriented themes, as they describe a predefined and sequential reconstruction for the organisational change initiative based on scientific knowledge. Subthemes coded as prescribing were evidence of operational change management, such as when top managers were displayed travelling “throughout Sweden to listen to how citizens, interest groups and agencies want the police to develop” (quote from Video 36). The other issues that the material revolved around were how regions were to be merged and how the change would resolve several technological problems associated with current policing systems.

In addition to this rhetoric of describing the reconstruction procedure, an all-inclusive approach involving potential critics was also an important feature of the theme. The police union was allowed to express some mild criticisms of the transformation. For example, in the context of discussing a unified police force, the concern that such a goal could lead to a centralised organisation was allowed to be aired and debated. We interpret this type of sensegiving as a rhetorical strategy that includes counterclaims of an argument to display credibility.

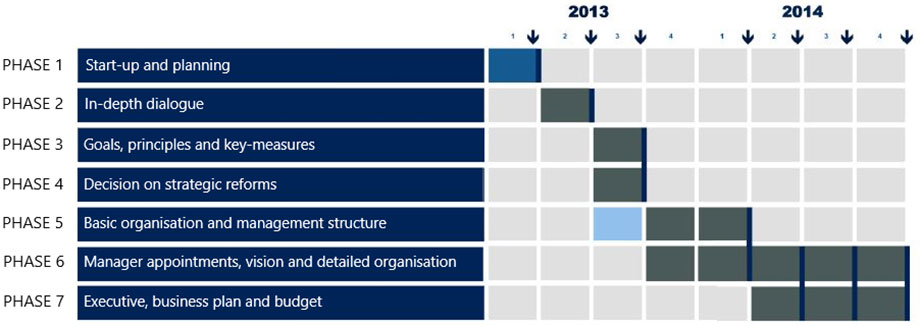

Semiotic modalities mobilised to express how change happens mainly emphasised activities by internal actors such as the change-management committee and leaders, supported by external expertise, and with middle managers and internal employees cast in the role of discussion partners or audience. Here, the viewer is presented with images of seemingly determined managerial representatives acting with and embodying confidence, credibility, and leadership. Regarding speech, this theme is characterised by a persuasive and solution-oriented tone wherein change is presented as a systematic, rational, and linear process tailored by experts. For example, the narrator voice, as well as external expert voices, regularly validate ideas about change. Other actors and voices that support this central narrative include audiences listening carefully to the messages. This is linked to imagery wherein change is presented as happening through strategic tools and project planning. To substantiate and promote these images, the material contains graphics such as timelines and phases that display how the organisation will change step by step. Figure 3 shows one such frequently used graphic that displays a sequential roadmap of change through a Gantt chart.

Figure 3

Gantt chart mapping the change process

With a strong emphasis on selling the change project, the imagery mobilised within this theme is predominantly focused on a detailed presentation of components of the change process. The high occurrence of change agents (mainly managers and the top change manager) combined with descriptions of the change process (as rational, democratic, and scientific) makes the overall portrayal of the change process similar to the typical recipe for organisational change found in the modern literature on change management.

3.4 Forecasting

We defined the fourth change-related theme as forecasting, which revolves mainly around presenting the future state of the organisation after implementing change. Hence, the term forecasting here refers to predicting what the change will lead to for the police. Several cultural features were central in the mediation of the future organisation. For example, after the reorganisation, the future police sector is promoted as a more employee-driven, cooperative, and professional institution that is mindful of the needs of the local community and thus puts the citizen first. In particular, much emphasis is placed on distributing more power to employees working in practical policing. As one local police manager put it: “we shift the mandate so the police officers on the spot become the ones who formulate the goals and find the methods. After all, they are the ones who know most about the current situation” (quote from video 41). On a par with cultural change, some structural changes in the new police service were also promoted, notably the creation of a centralised, more unified police force that would be more effective in its operations. Additionally, the police of the future are promoted as a flat (less hierarchical) and community-oriented organisation that listens to citizens. With these features, the future police force is described as more unified, more flexible, and aware of local needs (see also Lindberg et al. (2017) and The Swedish Agency for Public Management, (2016) for a description of this double objective).

This theme is the largest and most complex in its composition of semiotic resources and modes. In terms of actors, citizens and employees have a prominent role in the video material. Citizens are promoted as stakeholders who express needs and expectations regarding the police, whereas employees working with the change symbolise a broad anchoring and approval of the presumed future state of the organisation. In relation to this, management representatives are presented as listening to ideas and reflections while expressing how the organisation will function as a result of the change. Thus, the imagery that this theme draws on is largely teleological, focused on a final organisational design and purpose. Metaphorical images such as signed contracts and graphic representations of maps reinforce this message together with organisation charts and individuals (managers and employees) engaged with structuring through, for example, the use of Post-it Notes.

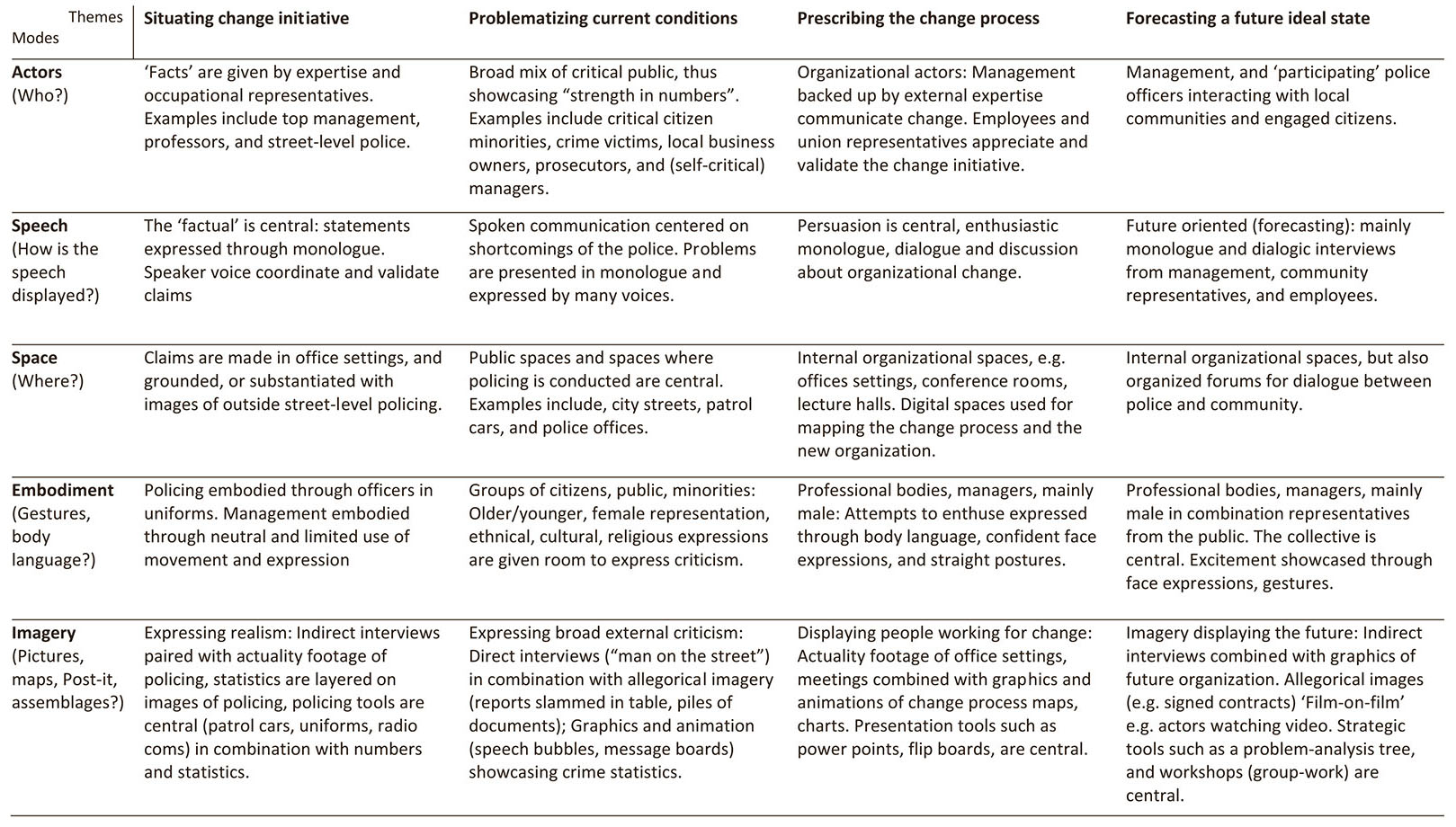

The speech is characterised by forecasts supporting the new organisation, commonly through dialogue in interview settings, whereas the overall message is one of optimism displayed through excited facial expressions and vivid gestures in tandem with hopeful verbal statements. In general, the promoted message is that the end-goal of the change initiative – one coherent and unified police authority – is a rational and self-evident step in the evolution of the police. In terms of space, Figure 4 illustrates how the future-oriented forecasting theme is defined by internal office settings in which groups of employees are engaged in discussion, reflecting on possible and positive future conditions.

Figure 4

Image of workshop

Figure 4 shows employees engaged in a workshop about the future organisation. It also illustrates how strategic tools used in workshops and meetings were a central feature of this theme.

We interpret the combination of modes within this sensegiving theme as a portrayal of the future organisation as something superior to the current one. Through positively expressed verbal statements and body language combined with affirmative images, including participating employees, responsive managers, creative reorganisation work, and complex organisational charts, the videos communicate a bright future. This theme initially appears as a multimodal composition of hope, belief, and promises – an image more reminiscent of ideals within management literature than the messy reality that often accompanies major changes.

4. Discussion

Our findings show how the police reorganisation used visual media to convey information about organisational matters. We categorised these efforts into four sensegiving themes: situating, problematising, prescribing, and forecasting. These themes demonstrate how the Swedish police reorganisation followed mainstream ideas of how strategic organisational change can be managed. The need to situate and problematise the present state of an organisation before changing is a well-known strategy on how to legitimise change. Kurt Lewin (1947) discussed this in terms of ‘unfreezing’ and ‘breaking’ of the present. Also, from a sensegiving perspective this type of destabilisation has been described as common early on in reorganisations and it has been discussed in terms of signalling of change (Gioia & Chittipeddi, 1991; Hensmans, 2015). Regarding the police reorganisation, the videos show how change early on was motivated and communicated through a process of problematising the present state of the organisation, wherein current ways of organising were critiqued and new ways of doing policing could be introduced. Also, the future-oriented themes of prescribing and forecasting that we identified show similarities with previous theories about organisational change, such as Lewin’s (1947) changing and ‘refreezing’ stages of organisational change wherein a new state of the organisation is introduced and anchored. In our case, this was evidenced by a preoccupation with the future and intense communication efforts to chart the way towards the future organisation. The preoccupation with the future is also underlined in the literature on police reform. Björk (2018, p.3) discussed this in terms of how “romantic” images of the future organisation were mobilised during change. Holgersson (2017, p.91) similarly discussed how police reforms are structured around “hopes”. Our findings show similarities with these accounts, as a central aspect of the videos was about the communication of an idealised future state of the organisation aimed to energise organisational members and build confidence for the planned change.

While the content analysis of the video material gives insights into what change was about, the second part of our analysis explains how change can be promoted as diverse semiotic modes are mobilised in parallel with the sensegiving themes (see Appendix 1 for an overview). Our multimodal analysis enabled us to identify two key features in communication about the police reorganisation: In the following, we discuss how two phenomena, namely ‘stereotyping’ and ‘layering’ were mobilised in the video material to address potential issues and criticisms towards the reorganisation. First, we will show how stereotypes and modal layering were arranged to legitimise change based on expert knowledge, and second, we will discuss how layering also functioned to downplay paradoxical tensions associated with the reform such as local versus centralised policing.

4.1 Expert knowledge and police reform

The notion that experts and expert knowledge can play a major role in police reforms has been recognised by other police related research. For example, Fyfe and Richardson, (2018, p. 153) discuss how expert knowledge can support change by the provision of substantiating epistemic authority. In essence, expertise can in this way “…give a ‘scientific’ authority to a preferred course of action”. Also, Degnegard (2010), in a commentary of Danish police reform critiqued the process based on it being an external technocratic process pushed by experts (see also Granér, 2017). As shown in our findings section, this tendency was present in the video material through the use of stereotypical external and internal experts. We conclude that three groups of stereotypical representatives were mobilised in the material with this purpose. We have labelled these groups of actors’ reality-descriptors, -confirmers, and -explainers.

The descriptors group consists of stereotypical individuals and groups whose role in the video material was to represent a negative current situation in the police sector. Examples include victims of crime (elderly adults appearing defenceless) and victims of injustice (youth living in deprived suburbs). In relation to these actors, two forms of expertise were cast in the videos to provide authority and knowledge about the need to change. First, what we call the confirmers are represented by stereotypical images of trustworthy, male, uniformed police management who validate descriptions of the current situation, thereby confirming current problems and the need for organisational change. Furthermore, these claims were substantiated by what we refer to as explainers who represent external expertise such as researchers, professors, and top-ranking chiefs of the implementation. Expert knowledge was thus given space in the material to explain the current situation, the motives behind the change, how it should be conducted, and the benefits for the future organisation. In this regard, the video analysis gives insights into how legitimacy is constructed and how credibility is an essential facet of sensegiving of change in the police reform. To present reality using stereotypes creates a compelling but simplistic portrayal of the organisation’s external context and internal practices, which paves the way for the advocated change initiative. The separation of actors into descriptors, confirmers and explainers that we have described also demonstrates a separation between administrative experts who were portrayed as directing and explaining the reorganisation and the rank-and-file police officers that are very sparsely portrayed in this regard. This separation indicates that the implementation of Swedish police reform primarily was an external project and that the implementation deviated from ambitions to conduct change “bottom-up” (Cameron, 2018). As Fyfe et al. (2018 p. 11) succinctly formulated this, the consequence of such separation is that change is “inflicted on the police rather than engineered by them”.

4.2 Tensions in the reform and multimodal layering

Another feature of communication is how the videos “layered” multiple modalities (i.e., actors, spaces, and images) to reinforce, or conversely downplay, messages about the change. Layering thus involves multimodal composition (Höllerer et al., 2018) to communicate key aspects of the change. Frequently, a verbal story (e.g., that change is necessary due to external demands) was layered with a visual story (e.g., change promoted by experts and managers) combined with a context that validated these stories (e.g., lecture hall or patrolling police officers). This type of layering is rhetorically effective (Höllerer et al., 2018), something that was particularly evident in relation to the potential issues of the reorganisation and how the videos addressed such issues. For example, from the outset of the police reform, a tension revolved the “double objectives” to on the one hand standardise the police and achieve national uniformity, and simultaneously increase local policing, improve flexibility and adapt to local conditions. This tension is well-described in the reform literature, (Björk, 2016; 2018; Cameron, 2017) and has previously been discussed as paradoxical (see Lindberg et al., 2017).

This tension recurrently surfaced in the analysis of the empirical material, often illustrated as two triangles (with one upside down) and discussed in terms of uniformity versus diversity, and hierarchy versus autonomy. When highlighting these issues, video sequences would regularly show images of discussion, problematisation and the voices from different perspectives as various images of meeting rooms, conferences, and forums for dialogue would be layered with actors such as union reps, employees, middle managers, change management, and civilians. In our interpretation, this rhetorical layering gives the viewer the impression that all perspectives and inputs were considered as equally important and that issues arising in the change were addressed and given full consideration. In this way, the video material shows simulated scenes of reorganisations where potential issues and criticisms are already addressed.

To summarise, multimodal stereotyping and layering are examples of how the films were created as effective sensegiving devices for constructing and legitimising key representations of change. However, while video is a potent tool in the hands of those in positions to portray change, it also provides members of an organisation and other actors with a unique opportunity to provide fine-grained information about several aspects of the change initiative (c.f. Figure 1). As such, sensegiving captured within a material artefact allows the unpacking and critical analysis of complex messages about change that might otherwise be lost.

5. Conclusion

Through a multimodal analysis of a video material produced as part of a change-management strategy, this paper contributes to research on police reform, but also to reform work and organisational change more generally. The analysis of video sequences gives insights into the central ideas that motivated change in the Swedish police reform. It also illuminates potential issues associated with the change and how the reorganisation was planned to be implemented in the police organisation. With this focus, the study adds an organisational change perspective to previous research on police reform that mainly has described the change from institutional and policy perspectives. Using a theoretical framework that draws on sensegiving and multimodality research, we conclude that the topics that were addressed in the material (i.e., the “what” of the change communication) shows a sequencing of the reform work that we classified in terms of situating, problematising, prescribing, and forecasting. This in turn shows similarities to mainstream ideas of change management as taking place through various stages wherein different messages are communicated (cf. Lewin, 1947). This finding gives support to previous research that has described the reorganisation as a process based on external management ideas and implementation strategies, rather than the specifics of policing (Björk, 2018; Granér, 2017).

Furthermore, we have analysed how key messages in the change were communicated rhetorically through several modalities (addressing the “how” of communication efforts). First, through an analysis of stereotypical imaging of actors in the material, we were able to address the role of expertise and expert knowledge in promoting change where our analysis indicated a clear divide between administrative powers that implemented reform and the rank-and-file of police officers. Second, through the notion of layering, our analysis widens the understanding of how verbal and visual resources are arranged to create persuasive accounts of change with the potential to legitimise courses of action and downplay tensions and paradoxes associated with change such as the tension between local flexibility and centralisation.

We conclude that video is a powerful sensegiving tool, as it provides opportunities to portray change. Certain aspects can be disguised, emphasised, neglected, or celebrated to serve different communicative purposes and organisational goals. As such, an analysis of this type of material provides insights into the discourse of change. Adding to such accounts, future studies could analyse the outcomes of sensegiving of organisational members to provide insights into how the messages are understood and enacted locally, and with which consequences for the organisational change initiative.

Appendix 1. Overview sensegiving themes and modes

References

-

Alvesson, M., &Kärreman, D.(2007). Constructing mystery: Empirical matters in theory development.

Academy of Management Review

, 32(4), 1265–1281. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.26586822 -

Björk, M.(2016).

The large police reform: Five working papers

(1st ed.).Studentlitteratur

. -

Björk, M.(2018). Muddling through the Swedish police reform: Observations from a neo-classical standpoint on bureaucracy.

Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice

15(1), 327–339. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pay069 -

Cameron, I.(2017). The Swedish Police after the 2015 reform: Emerging findings and new challenges.

Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice

, 15(1), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pax088 -

Chan, J.(2007). Making sense of police reforms.

Theoretical Criminology

, 11(3), 323–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480607079581 -

Cornelissen, J. P.,Clarke, J. S., &Cienki, A.(2012). Sensegiving in entrepreneurial contexts: The use of metaphors in speech and gesture to gain and sustain support for novel business ventures.

International Small Business Journal

, 30(3), 213–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610364427 -

Degnegaard, R.(2010).

Strategic change management: Change management challenges in the Danish police reform

.Copenhagen Business School. CBS

. -

ELAN. (2017).

Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Language Archive

. -

Fyfe, N. R.,Anderson, S.,Bland, N.,Goulding, A.,Mitchell, J., &Reid, S.(2018). Experiencing organisational change during an era of reform: Police Scotland, narratives of localism, and perceptions from the ‘Frontline.’

Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice

, 15(1), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pay052 -

Fyfe, N. R., &Richardson, N.(2018). Police reform, research and the uses of ‘expert knowledge.’

European Journal of Policing Studies

, 5(3), 147–162. -

Gioia, D. a., &Chittipeddi, K.(1991). Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation.

Strategic Management Journal

, 12(6), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250120604 -

Gioia, D. A.,Corley, K. G., &Hamilton, A. L.(2012). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology.

Organisational Research Methods

, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151 -

Granér, R.(2017). Literature on police reforms in the Nordic countries.

Nordisk politiforskning

, 4(02), 138–148. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1894-8693-2017-02-03 -

Granér, R., &Kronkvist, O.(2016). Control of and in the police organisation. InH. O. I. Gundhus,P. Larsson, &R. Granér(Eds.),

Police Science—An introduction

.Studentlitteratur AB

. -

Guiette, A., &Vandenbempt, K.(2016). Learning in times of dynamic complexity through balancing phenomenal qualities of sensemaking.

Management Learning

, 47(1), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507615592112 -

Hensmans, M.(2015). The Trojan horse mechanism and reciprocal sense-giving to urgent strategic change. In

Journal of Organizational Change Management

28(6). https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-06-2015-0084 -

Holgersson, S.(2017).

The Police’s Control Centers

.Linköping University Electronic Press

. -

Höllerer, M. A.,Jancsary, D., &Grafström, M.(2018). ‘A picture is worth a thousand words’: Multimodal sensemaking of the global financial crisis.

Organization Studies

, 39(5–6), 617–644. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618765019 -

Iedema, R.(2003). Multimodality, resemiotization: Extending the analysis of discourse as multi-semiotic practice.

Visual Communication

, 2(1), 29–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357203002001751 -

Kihlberg, R., &Lindberg, O.(2020). Reflexive sensegiving: An open-ended process of influencing the sensemaking of others during organizational change.

European Management Journal

, 39(4), 476-486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2020.10.007 -

Kotter, J. P.(2002).

The heart of change: Real-life stories of how people change their organizations

.Harvard Business School Press

. -

Kotter, J. P.(2012).

Leading Change

.Harvard Business Review Press

. -

Kraft, A.,Sparr, J. L., &Peus, C.(2015). The critical role of moderators in leader sensegiving: A literature review.

Journal of Change Management

, 15(4), 308–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2015.1091372 -

Leeuwen, T. Van.(2005).

Introducing Social Semiotics

.Routledge

. -

Lewin, K.(1947). Frontiers in group dynamics: Concept, method and reality in social science; social equilibria and social change.

Human Relations

, 1(1), 5–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872674700100103 -

Lindberg, O.,Rantatalo, O., &Hällgren, M.(2017). Making sense through false syntheses: Working with paradoxes in the reorganization of the Swedish police.

Scandinavian Journal of Management

33(3), 175-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2017.06.003 -

Maier, C. D.(2014). Multimodal aspects of corporate social responsibility communication.

LEA – Lingue e Letterature d’Oriente e d’Occidente

, 3, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.13128/LEA-1824-484x-15195 -

Nichols, B.(2001).

Introduction to Documentary

.Indiana UP

. -

Nvivo 11 Pro (Nvivo 11 Pro). (2015). [Software]. QSR software products.

-

Official Reports of the Swedish Government. (2015).

Final Report from the Implementation Committee for the New Police Authority

. -

Police Organizing Committee (Ed.). (2012).

A Coherent Swedish Police

.Fritzes

. -

Pratt, M. G.(2000). The good, the bad, and the ambivalent: Managing identification among Amway distributors.

Administrative Science Quarterly

, 45, 456–493. https://doi.org/doi:10.2307/2667106 -

Rouleau, L., &Balogun, J.(2011). Middle managers, strategic sensemaking, and discursive competence.

Journal of Management Studies

, 48(5), 953–983. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00941.x -

The Swedish Agency for Public Management. (2016).

The Transformation into a Coherent Police Authority, Part 1 on the Implementation Work

(Evaluation 2016:22). http://www.statskontoret.se/globalassets/publikationer/2016/201622.pdf -

The Swedish Agency for Public Management. (2017).

The Transformation into a Coherent Police Authority, Part 2, on the Impact of the New Organization

(Evaluation 2017:10). http://www.statskontoret.se/globalassets/publikationer/2017/201710.pdf -

The Swedish Agency for Public Management. (2018).

The Transformation into a Coherent Police Authority. Final report.

(Evaluation 2018:18; p. 112). -

Toraldo, M. L.,Islam, G., &Mangia, G.(2016). Modes of knowing: Video research and the problem of elusive knowledges.

Organizational Research Methods

, 21(2), 438–465. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428116657394 -

Virkkula-Raisanen, T.(2010). Linguistic repertoires and semiotic resources in interaction: A Finnish manager as a mediator in a multilingual meeting.

Journal of Business Communication

, 47(4), 505–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943610377315 -

Wennström, B.(2014).

Swedish Police: The Piece That not Fit the Puzzle

.Jure

.