Information Sharing Between Authorities Combating Foreign Labour Exploitation in Finland

Senior researcher

Police University College, Tampere, FinlandCorresponding author

Researcher

Police University College, Tampere, Finland, and Emergency Services Academy FinlandResearcher

Police University College, Tampere, FinlandPublisert 17.11.2023, Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing 2023/1, side 1-16

Well-functioning information sharing is an essential element for successful cooperation between authorities in public administration, e.g., when authorities attempt to combat foreign labour exploitation. This paper contributes toward existing literature by broadening the understanding about factors that need to be acknowledged when developing information sharing practices between authorities. The purpose of this study was to analyse authorities’ perceptions of possibilities and obstacles to share information with a focus on legislation, IT infrastructure and the set of electronic registers. In this case, the authorities were those whose legal duties include supervision of work-related immigration. In addition to a summary of legislation, empirical data was used. An electronic questionnaire was sent to 14 relevant authorities (62 respondents); 12 authorities responded. Knowledge gaps related to legislation and content of information were found to hamper information sharing between authorities. In addition, IT infrastructure capability and the fragmented nature of data registers, the so-called ‘silo effect’, complicates information distribution. To secure efficient and smooth information sharing, authorities need to know their legal possibilities and their duties to share information, but also understand what information is valuable to other authorities. In addition, IT infrastructure capability needs to be developed further. Finally, increasing knowledge about legal aspects is an important topic in education.

Keywords

- labour exploitation

- information sharing

- cooperation

- education

1. Introduction

In recent years in Finland, an increasing number of media outlets have brought up the unjust treatment and exploitation of migrant workers. The need to increase general knowledge on labour exploitation as well as develop official processes and supervision has been recognised. As part of the strategy for combating the grey economy, in spring 2020 a working group was appointed by the Minister of Employment to prepare measures to combat labour exploitation. The working group highlighted that one essential challenge was related to information exchange between authorities. Even though authorities were seen to get information from various channels, information was not exchanged and shared actively. As a result, e.g., tip-offs may be recorded and used by one authority only, thus setting cost-efficient multiprofessional cooperation at a disadvantage.

Several immigration bodies deal with migration matters. The Ministry of the Interior formulates Finland’s migration policy and is responsible also for overall legislation on migration and citizenship. The Finnish Immigration Service issues residence permits, processes citizenship applications and handles foreign passports as well as gathers information for the authorities and national and international cooperation. When investigating cases of human trafficking, the police work in cooperation with other authorities and third-sector operators. The Finnish Border Guard monitors entry into and departure from the country. The Finnish Security and Intelligence Service uses civilian intelligence to monitor threats to national security. In addition, there are several actors outside the Ministry of the Interior’s branch of government, the responsibilities of which include immigration matters. For example, Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment plan and coordinate the integration of immigrants at the regional level. The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment is responsible for policies and legislation concerning the migration of workers. These governmental agencies are engaged in the information sharing also when combating the exploitation of foreign labour.

In Finland, labour exploitation cases are classified as a form of economic crime. According to the Police information system, the total number of cases related to coercive work discrimination and human trafficking has increased during recent years. In 2015, there were a total of 45 cases, whereas in 2021 the number was 206. Human trafficking has been mainly related to cases of sexual or labour exploitation.

While defining and detecting exploitation is not simple, Yoshihara & Venetsiani (2018, p. 381) have defined it as a situation in which “A exploits B if and only if A takes unfair advantage of B”. Typically, the perpetrator aims to gain financial benefit by subjugating people in a weak position or victims that are dependent on the offender. Although the person in the weaker position might also benefit from the arrangement, which can make identifying exploitation more difficult, Yoshihara & Venetsiani’s definition includes an aspect of power imbalance. Lietonen et al. (2020a, pp. 13–14) reported several forms of labour exploitation. Restriction of freedom might take the form of confiscating the employees’ identity document or withholding their bank card, forbidding their social interactions, or restricting their movement. Employees may work overlong hours or receive no extra pay, e.g., from overtime work. Issues with wages or fees can include underpayment or withholding pay, or charging extra or unreasonable fees, such as transportation, recruitment or accommodation fees. These forms of exploitation are made possible through the employee’s position of dependence in relation to employer, which can result from, e.g., lack of knowledge of local language and customs, or fear of negative consequences such as violence towards the employee or someone close to them, among other reasons (see Lietonen et al., 2020a, pp. 13–14, 52–54).

Foreign labour exploitation concerns migrant workers, who can be either EU citizens or from third countries. Foreign labour exploitation takes place in different fields of work, such as agriculture, the construction industry, cleaning, or the restaurant industry, and migrant workers who are unaware of their rights, have a low level of education or a background with poverty or unemployment in their country of origin are especially vulnerable to exploitation (FRA 2015, p. 11, 14; Pekkarinen et al., 2021, p. 10).

As we see, foreign labour exploitation and work-related exploitation can be characterised as multiform phenomena, the prevention and pre-investigation of which requires deep understanding about their characteristics and manifestation. As a result, multidisciplinary expertise, information sharing and cooperation between authorities play a key role in combating them (see, e.g., Cockbain et al., 2018, p. 337). Bigdeli et al. (2013, p. 156) highlighted that public agencies are often “unaware under what law, policy or framework they can share information they have gathered with others”. In addition, information that is shared or should be shared is often sensitive as it is related to crime and the conditions that contribute to crime.

The issue of human trafficking and foreign labour exploitation is widespread in many societies, hampering the working of a healthy economy and causing human suffering. Finland is not alone in working against these crimes, and although there have been significant efforts against human trafficking and foreign labour exploitation, there is still work to be done. The phenomenon of human trafficking and foreign labour exploitation was identified in the early 2000s, and activities to counter them have been developed and become part of various national authorities’ and other parties’ work ever since (Jokinen et al., 2023). In addition, as mentioned, there has been growing interest both politically and within public discussions on migrant workers. Our case study focuses on the Finnish perspective of developing the exchange of information between national authorities, but with the hope of also benefitting authorities in other countries that face similar circumstances. Case studies in general are used in the social sciences to describe phenomena that are difficult to measure, and allow high levels of conceptual validity (George & Bennett 2005, p. 19).

Law enforcement agencies have raised concerns about information sharing in labour exploitation on the grounds of its legality and potentially its inadequate protections for privacy and civil rights. The purpose of this study was to analyse authorities’ perceptions about the possibilities of and obstacles to information sharing, with a focus on legislation, IT infrastructure and the electronic registers. Those authorities whose legal duties include the supervision of work-related immigration were included in the analysis. Information sharing theory was used as the basis for theoretical analysis. Specifically, we aimed to address the legal framework as well as infrastructure capability, covering the set of electronic registers. Thus, this paper contributes towards existing literature by broadening the understanding about factors that need to be acknowledged when developing information sharing between authorities that combat foreign labour exploitation. This paper originates from a project carried out between January and August 2021 by the Finnish Police University College. After the introduction, this article introduces theoretical considerations on information sharing. Then the data is introduced, and the factors hampering information sharing are presented. Finally, the results are discussed, and practical implications and future considerations are made.

2. Analytical framework

Information sharing theory provides tools to analyse factors constraining information sharing between authorities that combat foreign labour exploitation. The theory is based on the hypothesis that “organizational culture and policies as well as personal factors can influence people’s attitudes about information sharing” (Constant et al., 1994, p. 401). Information sharing has multiple elements, including social, legal, technological and behavioural types. Thus, there are aspects to it beyond the purely economic. (Rafaeli & Raban 2005, p. 62; Zaheer & Trkman 2017, pp. 430–432) We adopted the same definition of information sharing as, e.g., Plecas et al. (2011, p. 121): information sharing “involves collecting and organizing facts and figures (i.e. data), giving context to data, and providing information to various other individuals and/or organizations for strategic and operational decision making”. In addition, another relevant theory to the topic of information sharing between authorities would be institutional theory, which, similarly to information sharing theory, considers the relevance of, e.g., rules, norms, and cultural belief systems (Fuenfschilling & Truffer 2014, p. 774).

The complexity of information sharing becomes evident in previous research on the topic. Information can be defined as “data that have been analysed and/or contextualized, carries a message and makes a difference as perceived by the receiver” (Ahituv & Neumann, 1986 [in Rafaeli & Raban, 2005, p. 63]). In some definitions, information has been positioned between data and knowledge. While information lacks the richness of knowledge, the outer context and structure separates it from data. (Galliers & Newell, 2001 [in van Vuuren, 2011, p. 20]). Previous research shows that people do not view information merely as a commodity that is separated from its presentation or channel. Information itself can be divided for example between tangible “product” and intangible “expertise” information. Tangible information can take forms such as written information or other “physical” end product, whereas intangible information can be, e.g., personal knowledge or experiences. Even the same information, such as statistical information, can have different impacts or be perceived very differently, whether in tangible or intangible form. (Constant et al., 1994, p. 405.)

Assuming that information is accurate, error-free, concise, usable, and consistent, information sharing may create multiple benefits (Zhu & Wang, 2009; Kahn et al., 2002 [in Plecas 2011, p. 121]). For government agencies that potentially use the same overlapping information, sharing is the foundation for streamlining the collection, organisation, maintenance, and distribution of data and information as well as helping to share resources. With the help of information sharing, it is possible to get better quality and more comprehensive information for decision making and problem solving, as well as to increase productivity, improve performance, collaborate on efforts, make more productive use of limited resources, improve policy making, integrate public services and help build professional relationships. (Zhang, et al., 2005, p. 557; Dawes 1996, p. 384; Dean et al., 2006, p. 431; Bigdeli et al., 2013, p. 148; Kembro et al., 2014, pp. 615–617; Desouza, 2009, 1219, p. 1225.) Information sharing was also found to be of crucial importance when authorities are implementing risk-based targeted supervision to combat labour migration abuse (Kuukasjärvi et al., 2022, p. 12). However, information sharing may also be associated with risks. Bigdeli et al., (2013, p. 161) highlighted non-technological risks such as the risk of stigmatisation, risk of spreading and leaking citizens’ information as well as the risk of blame for employees if information sharing fails.

Researchers have highlighted several factors that promote information sharing. Having a common goal, shared purpose, trust, group identity, incentive mechanisms, reciprocity and technological usability will boost information sharing (Rafaeli & Raban, 2005, p. 68, pp. 73–74; Wu et al., 2009, pp. 88–91; van Vuuren, 2011, p. 11; Setak et al., 2018, p. 276). Shared sense of purpose and trust etc. were also referred to as social capital factors in previous studies such as, e.g., van Vuuren, (2011, p. 11, 141). Technological solutions can improve awareness and greater efficiency support as well as facilitate information sharing between law enforcement organisations (Plecas et al., 2011, p. 120, 131). However, it is worth noting that a variety of factors, such as the quality of information, may promote or hinder sharing depending on the circumstances (Rafaeli & Raban, 2005, pp. 73–74; Bigdeli et al., 2013, p. 155).

There may exist several limitations that have the potential to hamper information sharing. Social systems are related to, e.g., networks, professional development associations, educational and socialisation systems. Social challenges may occur if there is, e.g., undeveloped trust and collaboration between partners. (Zaheer & Trkman, 2017, p. 431; Drake et al., 2004, p. 67, 74.) Too ambitious goals, divergent organisational priorities, lack of funding, data ownership as well as organisational and individual resistance to change may also complicate information sharing. In larger companies it may be easier to invest information sharing technologies as they have more resources to invest, compared to smaller firms. (Zhang et al., 2005, p. 557; Lam, 2005, p. 518; Vanpoucke et al., 2009, p. 1218.) Moreover, technical aspects, which refer to, e.g., IT infrastructure capabilities, may raise several problems. Organisations may use different and inadequate technological systems (Collier, 2006, p. 112; Desouza, 2009, p. 1261), and advanced systems may be complicated to implement (Vanpoucke et al., 2009, p. 1228–1235) or record similar information differently (Drake et al., 2004, p. 76).

Law enforcement agencies have raised concerns about information sharing on the grounds of legality and potentially inadequate protections for privacy and civil rights. Legal guidelines have been prepared to protect the confidentiality of citizens’ information as well as to guarantee that only those persons who are authorised can access or use information (Carter & Carter 2009, 1323, p. 1330; Landsbergen & Wolken, 2001, p. 208; Carter et al., 2016, p. 13; Plecas et al., 2011, p. 122). Privacy issues may also refer to concerns that, after information has been shared, the original authority is no longer able to control how it is disseminated (Carter & Carter, 2009, p. 1334). Personal competences may also influence – either boost or hamper – information sharing. When working with databases, people need to have some understanding of the software and technical terminology associated with databases and have adequate computer skills (Plecas et al., 2011, p. 131; Jarvenpaa & Staples, 2000, p. 145).

3. Data and methods

Data was collected in April–June 2021. In order to analyse the factors that might complicate information sharing between authorities, an electronic questionnaire was sent to 14 relevant authorities’ common mailboxes, the legal duties of which include the supervision of work-related immigration. The authorities were: Regional State Administrative Agency, Centre for Economic Development Transport and the Environment, National Bureau of Investigation, Finnish Immigration Service, National Police Board of Finland, Police departments, The Finnish Border Guard, Finnish Food Authority, Finnish Security and Intelligence Service, TE-services (Work permit services), Finnish Customs, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland, Ministry for Foreign Affairs in Finland, as well as Finnish Tax Administration including The Grey Economy Information Unit. Several organisations may supervise work-related immigration within one authority. Therefore, the questionnaire was sent to 62 organisations (covering 14 authorities); see Table 1.

Table 1

| Authority | Number of organisations supervising immigration within an authority |

|---|---|

| Centre for Economic Development Transport and the Environment | 15 |

| TE-services (Work permit services) | 14 |

| Regional State Administrative Agency | 11 |

| Police departments (Supervision of foreign nationals) | 11 |

| Finnish Tax Administration including The Grey Economy Information Unit | 2 |

| National Bureau of Investigation | 1 |

| National Police Board of Finland | 1 |

| Finnish Security and Intelligence Service | 1 |

| Ministry for Foreign Affairs in Finland | 1 |

| Finnish Immigration Service | 1 |

| The Finnish Border Guard | 1 |

| Finnish Food Authority | 1 |

| Finnish Customs | 1 |

| Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland | 1 |

| Total | 62 |

Concerning the Centre for Economic Development Transport and the Environment (15 offices) as well as TE-services (14 offices), the questionnaire was sent to all the authorities’ offices in Finland. Within the Regional State Administrative Agency, the questionnaire was sent to five Occupational health and safety agencies and six alcohol licensing agencies. The questionnaire was also sent to all 11 police departments with the request to forward the questionnaire to those whose duties include supervision of foreign nationals. Altogether 31 organisations responded (representing 12 authorities), yielding a response rate of 50%.

Supervision was extensively defined here, covering different types of actions. For example, the competence of Finnish Customs and the Finnish Food Authority does not directly include the supervision of immigration, but in their own field of operations they conduct field supervision. Respondents were instructed to reply to those questions that are related to their legal duties, therefore not necessarily all questions were answered by each participant.

The data consisted of a comprehensive range of variables from four thematic areas: 1) legislation related to work-related immigration, 2) state of information sharing and receiving, 3) data registries and analysis practices, 4) supervision practices and multiprofessional cooperation. In the theme Legislation, respondents were asked to report the primary laws regulating a) possibilities to obtain information from other authorities, b) entitlement to utilise information received from other authorities c) entitlement to give information to other authorities d) entitlement to give information to other authorities spontaneously. With the help of these questions, we aimed to possibly complement our review of legislation regarding the above-mentioned thematic areas as well as assess how well authorities know the legislation. Respondents were also asked to assess the functionality and clarity of legislation on the basis of several claims: a) Authorities competencies are clearly defined in legislation b) Legislation is not open to interpretations, c) Possibilities to use information obtained from other authorities are sufficient, d) Possibilities to share information with other authorities are sufficient, e) Possibilities to obtain information from other authorities are sufficient. A five-point rating was used to assess the functionality and clarity of legislation (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = slightly disagree, 3 = neither disagree nor agree, 4 = slightly agree and 5 = strongly agree). Open-ended questions encouraged respondents to consider whether current legislation should be developed from a supervision point of view and, if yes, in what ways.

Theme 2, “State of information sharing and receiving”, included open-ended questions. Respondents were asked to describe what kind of information from other authorities would help them in performing their activities. In addition, respondents were urged to illustrate the most appropriate model for information sharing between authorities operating in work-related supervision. The theme “Data registries and analysis practices” covered several open-ended questions. Respondents were asked to answer which main registers and possible other databanks are used in the supervision of work-related immigration. In addition, they were asked whether data analysis is utilised, and if so, what kind of analysis practices exist.

To find out the legal framework applied in supervision and pre-investigation of labour exploitation, the main legislation was gathered and analysed and the content summarised briefly. When gathering empirical data, recipients were asked to form one collective answer within their organisation. Therefore, the organisations were asked to collect their experts’ views and send responses at the organisational level and no personal information about respondents was collected. Open-ended responses were analysed qualitatively utilising content analysis. Quantitative responses are presented in this study in percentages.

4. Factors influencing information sharing

4.1 Legal framework

The legal framework defines what actions organisations can undertake, i.e. the types of operations they can engage in. Finnish state agencies can only act within the boundaries of the law. Therefore, the law may be a hampering factor, but is also the basis for action. In Finland, there is no uniform national or international legal framework that regulates labour exploitation (Lietonen et al., 2020b, p. 14). When summarising legislation and legislative history, 22 separate laws were identified to regulate the supervision of work-related immigration, Appendix 1.

According to the Constitution of Finland (731/1999), “Documents and recordings in the possession of the authorities are public, unless their publication has for compelling reasons been specifically restricted by an Act.” Also, the Act on the Openness of Government Activities (621/1999) defines that “information on the activities of the authority is not unduly or unlawfully restricted, nor more restricted than what is necessary for the protection of the interests of the person protected”. However, “a secret official document, a copy or a printout thereof shall not be shown or given to a third party or made available to a third party by means of a technical interface or otherwise”. Cooperation between authorities is emphasised also in the Administrative Procedure Act: “An authority shall, within its competence and to the extent required by the matter, assist another authority, at its request, in performing an administrative duty and shall also otherwise seek to promote cooperation between authorities.”

When supervising work-related immigration, information utilised in supervision is personal data by nature or may be related to an organisation’s (such as a private company’s) activities. The processing of personal data in immigration administration is regulated in the Law of Processing Personal Data in Immigration Administration (615/2020). The Act on the Processing of Personal Data by the Police (616/2019) defines that the police is allowed to process personal data for the purpose of preventing and detecting offences, in investigations and surveillance, or when necessary for the performance of the statutory duties of the police. Personal data means, e.g., name, date and place of birth, gender, native language, civil status and travel document information and other information concerning entry into the country and border-crossing.

Empirical results revealed that even in the same administrative branch, there were differences in what laws were identified to regulate work-related immigration. We also aimed to assess the functionality and clarity of legislation from several aspects; see Table 2.

Table 2

| Fully/slightly disagree% | Neither agree nor disagree% | Fully/slightly agree% | Total% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authorities’ competencies are clearly defined in legislation | ||||

| Pre-investigation authorities (N=10) | 10 | 10 | 80 | 100 |

| Supervising authorities (N=16) | 69 | 13 | 19 | 100 |

| Others (N=5) | 20 | 20 | 60 | 100 |

| Legislation is not open to interpretations | ||||

| Pre-investigation authorities (N=10) | 30 | 20 | 50 | 100 |

| Supervising authorities (N=16) | 31 | 25 | 44 | 100 |

| Others (N=5) | 20 | 40 | 40 | 100 |

| Legal possibilities to get information from other authorities are sufficient | ||||

| Pre-investigation authorities (N=10) | 10 | 10 | 80 | 100 |

| Supervising authorities (N=16) | 56 | 13 | 31 | 100 |

| Others (N=5) | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Legal possibilities to share information to other authorities are sufficient | ||||

| Pre-investigation authorities (N=10) | 10 | 10 | 80 | 100 |

| Supervising authorities (N=16) | 31 | 19 | 50 | 100 |

| Others (N=5) | 60 | 0 | 40 | 100 |

| Legal rights to use information got from other authorities are sufficient | ||||

| Pre-investigation authorities (N=10) | 0 | 20 | 80 | 100 |

| Supervising authorities (N=16) | 63 | 6 | 31 | 100 |

| Others (N=5) | 0 | 20 | 80 | 100 |

In Table 2, the Pre-investigation authorities category included eight police departments, the Finnish Border Guard and Finnish Customs. The Supervising authorities category included eight Regional State Administrative Agencies, four Centres for Economic Development Transport and the Environment and four TE-services. The Other category included Finnish Immigration Service, Finnish Tax Administration, the Grey Economy Information Unit, Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Finland and the Finnish Food Authority. Pre-investigation authorities mostly saw that their competencies are clearly defined in legislation; also, about 60% of authorities in the Other category shared the same experience. However, almost 70% of supervising authorities had the opposite opinion. Half of pre-investigation authorities saw legislation as being open to interpretation at least to some extent.

Pre-investigation and other authorities were satisfied with their legal possibilities to get information from other authorities, but some 50% of the supervising authorities were not. Pre-investigation authorities were mostly (80% agreed with the claims) satisfied also with their legal possibilities to share information to other authorities and legal rights to use information got from other authorities. Supervising authorities do not seem to be satisfied with their legal rights to use information gained from other authorities, as over 60% fully or slightly disagreed with the claim.

4.2 Knowledge gap

There is a broad number of authorities operating in supervision of work-related immigration, and each authority’s competence is defined in several laws. As a result, authorities are not necessarily fully aware of each other’s possibilities to share information. In addition, authorities may be unaware of what information could be valuable to others.

In the questionnaire, authorities were asked to innovate practices for better information sharing. The results revealed that firstly it should be identified what information is needed. It seems to be somewhat unclear which information is valuable to other authorities and also whether some authorities already have the necessary information. To get a deeper understanding about the relevant information to each authority, the questionnaire included a question about what kind of information could possibly help authorities in their operational activities. Pre-investigation authorities reported that information about content of residence permits as well as information about persons’ tax and/or social benefits would be valuable for them. Also supervising authorities highlighted several types of information that would help them conduct operational duties: information about shortcomings related to different employers and/or lines of business and intelligence gathered by other authorities; in addition, information about the local labour market situation as well as the state of work-related immigration and the possible changes and malpractices. Supervising authorities also emphasised the need for information about whether the employer is suspected of committing a crime, e.g., of employment discrimination or exploitation. In addition, it was pointed out that information sharing should not be based only on individualised data, but also mass data is needed. Authorities have reported that both important isolated information as well as mass data should be shared via multiprofessional networks. Mass data is seldom exchanged via registers (Kuukasjärvi et al., 2021, p. 51, 66). The importance of national multiprofessional networks was also recognised by Ylinen et al. (2021). A study by Kurvinen et al. (2023) highlighted that according to police officers’ perceptions, they cannot exchange information (e.g., information obtained in traffic checks) on their own initiative to tax authorities.

4.3 IT infrastructure capability and data registers

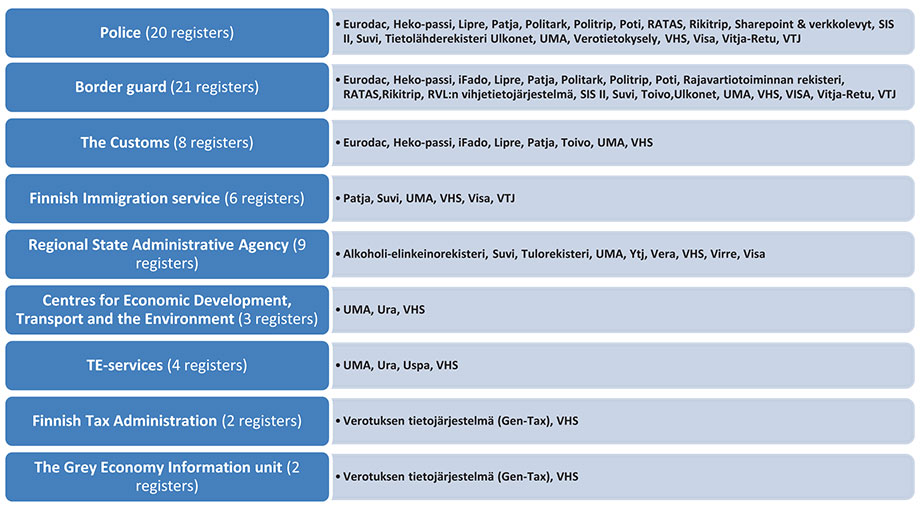

Accurate and well-timed information sharing facilitates multiprofessional proactive criminal justice approaches. The results revealed that the authorities that combat foreign labour exploitation operate across 31 different registers and information systems. These systems are related to authorities’ duties and may be legally accessed directly or with a limited right of use. The complexity of information systems is illustrated in Figure 1, which reveals the numbers and names of different registries that authorities can access.

Figure 1

Information systems and registers related to supervision of work-related immigration

Figure 1 illustrates clearly that the Police and Finnish Border Guard have good possibilities to obtain information when needed, as they can legally access at least 20 registers. We can also analyse the usability of registers on the basis of how many authorities are legally able to access each register. The Compliance Report service (VHS) is available to all authorities and is “illustrative of the level of compliance of an organisation or a person with statutory obligations. The report includes information on activities, financial standing and compliance with obligations related to taxes, statutory pension, accident insurance and unemployment insurance contributions and fees levied by Customs”. Also, the case management system for immigration matters (UMA) is often available, as 7 out of 9 authorities can legally access it. The results show that all other registries are legally quite limited to reach, as less than half of the authorities can access them. Therefore, we can say that the ‘silo effect’ characterises the storage of information related to the supervision of work-related immigration. When information needs to be shared between authorities, email, telephone and personal contacts were mentioned in the questionnaires as being the most relevant tools.

Authorities highlighted in questionnaire responses that technical prohibition to access various registers is not the only aspect related to IT infrastructure that may hamper information sharing between authorities. In Finland, information sharing between authorities is based on the principle of purpose affiliation. This means that “personal data may only be collected and processed for a specific and lawful purpose. The data may not be processed in a manner inconsistent with the original purpose at a later date.” The purpose for which a register can be used is defined accurately, e.g., in the file description. If information is planned to be utilised more widely than is defined in the register’s specification, utilisation is not legally necessarily possible, even if it would be technically possible. The General Data Protection Regulation must also be taken carefully into account. One limitation possibly hampering information sharing is the quality of data. Authorities recognised that the quality is dependent on the person who is storing the data in the register as well as his/her understanding of how to use the register. Search features should also be clearer and further elaborated.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Information sharing is a crucial contributory factor in multiprofessional cooperation between authorities. If information sharing is insufficient, it will impede, e.g., attempts to tackle labour trafficking (Cockbain et al., 2018, p. 337), or complicate the drafting of laws (Ministry of Justice, 2019). Dean et al. (2006, p. 431, 436) found that information sharing had a significant influence on all primary activities of the police investigation. Therefore, it is important to understand which factors may hamper the information sharing between authorities.

In Finland, authorities are not allowed to access or share information on the basis of their authority alone. Therefore, due to this separation principle, authorities are in a manner of speaking removed from each other. This study revealed several aspects that complicate information sharing. The legal framework defining authorities’ competences in the supervision of work-related immigration, as well as regulating their possibilities to share information, was found to be extensive. Legislation was also found to some extent to be open to interpretation. Interestingly, some authorities, even in the same administrative branch, identified partly different laws regulating work-related immigration. There may exist many reasons for varying responses. If supervision is addressed to a particular function or area of operations, respondents’ duties may differ also within the same employer and, therefore, also applicable legislation may vary. However, results may also indicate that authorities do not know this particular legislation well enough. If it is not exactly known which laws define the legal basis for information sharing, decisions to share or not to share information may be based on employees’ own interpretations of the law. If authorities also fear making mistakes, information may not be shared in such cases when it would be legally possible. An extensive study on information exchange has been published in Finland (Kurvinen et al., 2023); the findings of the study support the findings presented in this article. To fill in the possible legislation-related gaps in knowledge, more training should be offered. Dean et al. (2006, pp. 433–436) also suggested that police organisations should concentrate and facilitate learning processes, which could increase knowledge sharing among colleagues.

The results of this study revealed that there also exist information-related knowledge gaps, as authorities might not necessarily recognise what kind of information would be useful to other authorities. There may also exist a reluctance to share data in cases when data is classified, as Laczko & Gramegna (2003, p. 185) also reported. Wide-ranging information is collected, e.g., in supervision events, carried out in concert with all competent authorities, or when each authority visits operators as part of their normal duties. However, as authorities do not necessarily recognise what information is useful to other authorities, information is not necessarily stored and shared. Therefore, this study confirms the same results obtained previously, that undeveloped collaboration between partners may hamper information sharing.

We have also elaborated the knowledge-gap aspect from a data-content point of view when exploring exactly what kind of information would help authorities in their operational activities. Information about content of permits of residence as well as information about persons’ tax and/or social benefits were found to be valuable to pre-investigation authorities. Supervising authorities emphasised, e.g., the need for information about shortcomings related to different employers and/or lines of business as well as the state of work-related immigration and whether it has changed or been abused. Therefore, more open discussion between authorities and their duties and competencies is essential when developing information sharing practices. Ylinen et al. (2020, p. 19) suggested establishing a national network consisting of representatives from various authorities. This study also confirms the importance of networking.

Authorities supervising work-related immigration store and obtain information from 31 different registers. The Police and Border Guard have good possibilities to obtain information when needed, but supervising authorities’ possibilities are more limited. Thus, the storage of information related to the supervision of work-related immigration seems to suffer from the ‘silo effect’. The vast number of registers may prevent authorities from easily sharing relevant information to other relevant authorities for various reasons. Registers typically have, e.g., specific access codes and principles to store information, in which case the quality of data may be put at risk due to several people having access to the register and the variety of possibilities to store information. Poor data quality can in turn hamper information sharing, which is also pointed out in a study by Laczko & Gramegna (2003, p. 185). In addition, if information is planned to be utilised more widely as defined in the register’s specification, utilisation is not necessarily possible, even if it would be technically possible. One shared or common register/information system could simplify and foster information sharing, as also suggested by Laczko & Gramegna (2003, p. 191). Another possibility is to allow access to registers to all competent authorities. Whatever alternative is chosen, several IT-related aspects that currently complicate information sharing significantly need to be taken into account, and simplifying them needs to be considered.

Although the results of this study mostly confirm previous findings, there are some limitations to this study. First, the data collection was focused only on authorities and the empirical data was gathered at the organisational level. Thus, the individual responses and opinions were possibly hidden, as a combined view was collected. Second, the sample was to some extent limited as not all organisations’ responses were received. However, 50% of the recipients responded to the questionnaire. In addition, almost all authorities’ viewpoints were gathered as 12 out of 14 authorities responded to the questionnaire. However, caution must be applied when interpreting the results.

Questions remain that cannot be addressed in this study. For future research, we suggest an analysis of the factors that motivate persons to share information related to the supervision of work-related immigration. If cooperation and thus practices for information sharing are not developed within and between authorities, decisions to withdraw from information sharing may stem from old habits within the organisation, not necessarily from legislation itself. Also, actors in the private and third sectors could have useful information and tip-offs which could be utilised in uncovering illicit activities. Therefore, the role of these operators could be strengthened when combating labour exploitation and developing information sharing mechanisms. Laczko & Gramegna (2003, p. 184, 190) highlighted that compilation of reliable human trafficking data needs appropriate resources. Our data was not able to address this, but resources are definitely an important aspect to include in further analyses too.

To conclude, IT infrastructure capability alone is not enough to secure efficient information sharing, as authorities also need to know and understand what information is valuable to other authorities as well as their legal possibilities to share information. Therefore, legal framework and technical infrastructure are closely linked, and education about these aspects is needed.

References

-

Bigdeli, A. Z.,Kamal, M., &de Cesare, S.(2013). Information sharing through inter-organisational systems in local government.

Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy

, 7(2), 2013, 148–176. https://doi.org/10.1108/17506161311325341 -

Carter, D. L., &Carter, J. G.(2009). The intelligence fusion process for state, local, and tribal law enforcement.

Criminal justice and behavior

, 36(12), 1323–1339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854809345674 -

Carter, J. G.,Carter, D. L.,Chermak, S., &McGarrell, E.(2016). Law enforcement fusion centers: Cultivating an information sharing environment while safeguarding privacy.

Journal of police and criminal psychology

, 32(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-016-9199-4 -

Cockbain, E.,Bowers, K., &Dimitrova, G.(2018). Human trafficking for labour exploitation: the results of a two-phase systematic review mapping the European evidence base and synthesising key scientific research evidence.

Journal of Experimental Criminology

, 14(3), 319–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-017-9321-3 -

Collier, P. M.(2006). Policing and the intelligent application of knowledge.

Public Money and Management

, 26(2), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9302.2006.00509.x. -

Constant, D.,Kiesler, S., &Sproull, L.(1994). What’s mine is ours, or is it? A study of attitudes about information sharing.

Information systems research

, 5(4), 400–421. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23010604 -

Dawes, S. S.(1996). Interagency information sharing: Expected benefits, manageable risks.

Journal of policy analysis and management

, 15(3), 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6688(199622)15:3<377::AID-PAM3>3.0.CO;2-F -

Dean, G.,Filstad, C., &Gottschalk, P.(2006). Knowledge sharing in criminal investigations: an empirical study of Norwegian police as value shop.

Criminal justice studies

, 19(4), 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786010601083694 -

Desouza, K. C.(2009). Information and knowledge management in public sector networks: The case of the US intelligence community.

Intl Journal of Public Administration

, 32(14), 1219–1267. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900690903344718 -

Drake, D. B.,Steckler, N. A., &Koch, M. J.(2004). Information sharing in and across government agencies: The role and influence of scientist, politician, and bureaucrat subcultures.

Social science computer review

, 22(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439303259889 -

FRA – European Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2015).

Severe labour exploitation: workers moving within or into the European Union. States’ obligations and victims’ rights.

Luxembourg

:Publications Office of the European Union

. -

Fuenfschilling, L.&Truffer, B.(2014). The structuration of socio-technical regimes: Conceptual foundations from institutional theory.

Research Policy

43 (2014) 772–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.10.010 -

George, A. L.&Bennet, A.(2005).

Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences.

MIT Press

. -

Jokinen, A.,Ollus, N., &Pekkarinen, A-G.(2023).

Review of actions against labour trafficking in Finland HEUNI Report Series No. 99b

. -

Kahn, B. K.,Strong, D. M., &Wang, R. Y.(2002). Information quality benchmarks: product and service performance.

Communications of the ACM

, 45(4), 184–192. https://doi.org/10.1145/505248.506007 -

Kembro, J.,Selviaridis, K., &Näslund, D.(2014). Theoretical perspectives on information sharing in supply chains: a systematic literature review and conceptual framework.

Supply chain management: An international journal

. 19/5/6 (2014), 609–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-12-2013-0460 -

Kuukasjärvi, K.,Rikkilä, S.,Kankaanranta, T.(2021).

“Selvitys tietojenvaihdon ja analyysitoiminnan katvealueista työperäisen maahanmuuton valvonnan moniviranomaisyhteistyössä”.

(Available at: https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2021110954521) -

Kuukasjärvi, K. M.,Rikkilä, S., &Kankaanranta, T.(2022).

“Matalat kynnykset on helpointa ylittää”: työperäisen hyväksikäytön ja ihmiskaupan torjunta moniviranomaistoiminnassa.

Poliisiammattikorkeakoulun raportteja 142.Poliisiammattikorkeakoulu, Tampere

. -

Kurvinen, E.,Ahokas, K.,Elmerot, Å.,Hassinen, T.,Havre, M.,Kuukasjärvi, K.,Laitinen, K.,Launiala, M.,Määttä, K.,Salumaa-Lepik, K.,Sariola, M.,Tiura-Virta, H.,Voutilainen, T.(2023).

Self-initiated access to information to crime prevention.

Publications of the Government’s analysis, assessment and research activities 2023:39. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-383-216-9 -

Laczko, F., &Gramegna, M. A.(2003). Developing better indicators of human trafficking.

The Brown Journal of world affairs

, 10(1), 179–194. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24590602 -

Lam, W.(2005). Barriers to e-government integration.

Journal of Enterprise Information Management

, Vol. 18 No. 5, 2005, 511–530. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410390510623981 -

Landsbergen Jr, D., &Wolken Jr, G.(2001). Realizing the promise: Government information systems and the fourth generation of information technology.

Public administration review

, 61(2), 206–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00023 -

Lietonen, A.,Jokinen, A., &Ollus, N.(2020a).

Navigating through your supply chain: Toolkit for prevention of labour exploitation and trafficking.

HEUNI Publication Series No. 93a. Yhdistyneiden Kansakuntien yhteydessä toimiva Euroopan Kriminaalipolitiikan Instituutti (HEUNI), Helsinki. HEUNI-Publication-Series-93a-FLOW-Toolkit-for-Responsible-Businesses-Web.pdf. -

Lietonen, A.,Jokinen, A., &Pekkarinen, A. G.(2020b).

Normative framework guide: responsibility of businesses concerning human rights, labour exploitation and human trafficking.

Available at: https://repositorium.ixtheo.de/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10900/120612/Normative_Heuni_94_16592.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 10.3.22 -

Ministry of Justice, Cooperative working group for improving law drafting. (2019).

Final report of the cooperative working group for improving law drafting.

Publications of the Ministry of Justice, Memorandums and statements 2019:29

. -

Pekkarinen, A-G.,Jokinen, A.,Rantala, A.,Ollus, N.&Näsi, R.(2021).

Report on the methods of preventing the exploitation of migrant labour in different countries. (Selvitys ulkomaisen työvoiman hyväksikäytön torjunnan menettelyistä eri maissa).

Publications of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment 2021:5 -

Plecas, D.,McCormick, A. V.,Levine, J.,Neal, P., &Cohen, I. M.(2011). Evidence-based solution to information sharing between law enforcement agencies.

Policing: An International journal of police strategies & management

, 34(1), 120–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639511111106641 -

Rafaeli, S., &Raban, D. R.(2005). Information sharing online: a research challenge.

International Journal of Knowledge and Learning

, 1(1–2), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJKL.2005.006251 -

Setak, M.,Kafshian Ahar, H., &Alaei, S.(2018). Incentive mechanism based on cooperative advertising for cost information sharing in a supply chain with competing retailers.

Journal of Industrial Engineering International

, 14(2), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40092-017-0225-7 -

Vanpoucke, E.,Boyer, K. K., &Vereecke, A.(2009). Supply chain information flow strategies: an empirical taxonomy.

International Journal of Operations & Production Management

, 29(12), 1213–1241. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570911005974 -

van Vuuren, J. S.(2011).

Inter-organisational knowledge sharing in the public sector: the role of social capital and information and communication technology.

Doctoral Thesis,Victoria University of Wellington

, 2011. -

Zaheer, N., &Trkman, P.(2017). An information sharing theory perspective on willingness to share information in supply chains.

The International Journal of Logistics Management

, 28(2), 417–443. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-09-2015-0158 -

Zhang, J.,Dawes, S. S., &Sarkis, J.(2005). Exploring stakeholders’ expectations of the benefits and barriers of e-government knowledge sharing.

Journal of Enterprise Information Management

, 18(5), 548–567. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410390510624007 -

Zhu, H.,Wang, R.Y.(2009). Information Quality Framework for Verifiable Intelligence Products. In:Chan, Y.,Talburt, J.,Talley, T.(eds)

Data Engineering.

International Series in Operations Research & Management Science, 132, 315–333.Springer

,Boston, MA

. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0176-7_14 -

Yoshihara, N.&Veneziani, R.(2018). The theory of exploitation as the unequal exchange of labour.

Economics & Philosophy

, 34(3), 381–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266267118000238 -

Wu, W. L.,Lin, C. H.,Hsu, B. F., &Yeh, R. S.(2009). Interpersonal trust and knowledge sharing: Moderating effects of individual altruism and a social interaction environment.

Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal

, 37(1), 83–93.https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2009.37.1.83 -

Ylinen, P.,Jokinen, A.,Pekkarinen, A-G.,Ollus, N.,Jenu, K-P.&Skur, T.(2020).

Uncovering labour trafficking: Investigation tool for law enforcement and checklist for labour inspectors.

HEUNI Publication Series No. 95a.The European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI), Helsinki

. https://heuni.fi/documents/47074104/0/ENG-InvestigationAid_Web+2_14072020.pdf/f7196ce4-124f-dfd2-3113-b8ef7fce3d54/ENG-InvestigationAid_Web+2_14072020.pdf?t=1606915478428

Appendix 1

-

The Alcohol Act (Alkoholilaki 1102/2017)

-

Administrative Procedure Act (Hallintolaki 434/2003)

-

Act on The Grey Economy Information Unit (Laki Harmaan talouden selvitysyksiköstä 1207/2010)

-

The Act on the Processing of Personal Data in the Field of Immigration Administration (Laki henkilötietojen käsittelystä maahanmuuttohallinnossa 615/2020)

-

Act on the Processing of Personal Data by the Police (Laki henkilötietojen käsittelystä poliisitoimessa 616/2019)

-

Act on the Processing of Personal Data by the Border Guard (Laki henkilötietojen käsittelystä Rajavartiolaitoksessa 639/2019)

-

Act on the Processing of Personal Data in Criminal Matters and in Connection with Maintaining National Security (Laki henkilötietojen käsittelystä rikosasioissa ja kansallisen turvallisuuden ylläpitämisen yhteydessä 1054/2018)

-

Act on the Promotion of Immigrant Integration (Laki kotouttamisen edistämisestä 1386/2010)

-

Act on Public Employment and Business Service (Laki julkisesta työvoima- ja yrityspalvelusta 916/2012)

-

Act on Cooperation between the Police, Customs and the Border Guard (Laki poliisin, Tullin ja Rajavartiolaitoksen yhteistoiminnasta 687/2009)

-

Act on the Administration of the Border Guard (Laki Rajavartiolaitoksen hallinnosta 577/2005)

-

Act on Occupational Safety and Health Enforcement and Cooperation on Occupational Safety and Health at Workplaces (Laki työsuojelun valvonnasta ja työpaikan työsuojeluyhteistoiminnasta 44/2006)

-

Act on Posting Workers (Laki työntekijöiden lähettämisestä 447/2016)

-

Act on Assessment Procedure (Laki verotusmenettelystä 1558/1995)

-

Act on the Public Disclosure and Confidentiality of Tax Information (Laki verotustietojen julkisuudesta ja salassapidosta 1346/1999)

-

Act on the Openness of Government Activities (Laki viranomaisten toiminnan julkisuudesta 621/1999)

-

Police Act (Poliisilaki 872/2011)

-

Constitution of Finland (Suomen perustuslaki 731/1999)

-

Data Protection Act (Tietosuojalaki 1050/2018)

-

Security Clearance Act (Turvallisuusselvityslaki 726/2014)

-

Employment Contracts Act (Työsopimuslaki 55/2001)

-

Aliens Act (Ulkomaalaislaki 301/2004)

- 1

- 2

- 3In the Criminal Code of Finland, labour exploitation is criminalised, e.g., as work discrimination, extortionate work discrimination, aggravated usury, or human trafficking.

- 4The figures include: Trafficking in human beings, Aggravated trafficking in human beings, Attempted commission of trafficking in human beings, Attempted commission of aggravated trafficking in human beings, and Extortionate work discrimination.

- 5

- 6The main results of the project were presented in the final report by Kuukasjärvi, K., Rikkilä, S., Kankaanranta,T. (2021): “Selvitys tietojenvaihdon ja analyysitoiminnan katvealueista työperäisen maahanmuuton valvonnan moniviranomaisyhteistyössä”.

- 7Six Regional State Administrative Agencies, covering Alcohol licensing, sent one collective response. In the data set, this was analysed as six identical responses.

- 8A detailed description of each register’s content is beyond the scope of this article.

- 9

- 10