The Investigation of Online Child Sexual Abuse Cases in Sweden

Organizational Challenges and the Need for Collaboration

PhD student

Department of Education and Unit of Police Work, Umeå University, Umeå, SwedenCorresponding author

Associate professor

Department of Education, Umeå University, Umeå, SwedenAssociate professor

Department of Education, Umeå University, Umeå, SwedenAssociate professor

Department of Psychology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden and Department of Health, Education and Technology, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, SwedenPublisert 04.11.2024, Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing 2024/1, Årgang 11, side 1-15

Investigating online child sexual abuse (CSA) crimes is challenging for law enforcement agencies, demanding both digital expertise and knowledge about offences against children while exacting a mental toll on investigators. This article identifies challenges in the investigative process, drawing on audit reports, interviews with police management, observations of meetings, and a workshop with online CSA investigators. The findings reveal difficulties in resource allocation due to varying case sizes and rapid escalation. In addition, while online CSA investigators handle most cases, they require support from other police units; however, a widespread fear of these cases among non-specialized investigators complicates collaborative efforts. Lastly, a culture of organizational “compartmentalization” was described as hindering collaboration, as different branches of investigation remain separated. We discuss how these challenges pose problems to online CSA investigation practices.

Keywords

- online child sexual abuse

- CSAM

- police investigation

- criminal investigation

- CSA

1. Introduction

Criminal investigation of online child sexual abuse (CSA) is a growing challenge in an age when the digital landscape is rapidly changing. In recent years, we have seen a surge in online sexual abuse crimes that has presented law enforcement agencies with substantial organizational challenges (cf. Internet Watch Foundation, 2023). As technology advances, so does the modus of these crimes, requiring a blend of forensic expertise and a profound understanding of sexual offences against children and child victim interviewing for investigation (Sunde & Sunde, 2022; Whelan & Harkin, 2021). This article examines the investigation process of online CSA crimes, shedding light on challenges faced by the investigators.

In the Swedish policing system, these cases are investigated by specialized online CSA units working regionally across several local police districts (Swedish Police Authority, 2022). The majority of the cases are prosecutor-led, where the prosecutor works together with a specialized investigator. The investigator then engages other provisional resources, such as IT forensics, that serve specific but temporary duties in the investigation (Swedish Police Authority, 2022). This is a common approach also across other policing systems (cf. Martellozzo, 2015).

To exemplify the increase in online CSA cases, the Swedish police received 4,596 reports of online CSA in 2017; three years later, that number had surged to 13,153 (Riksrevisionen, 2021). Adding to this, a single case can contain large quantities of child exploitation material and span national borders as web hosts, proxy servers and cloud services have global reach (Henry & Powell, 2018; Martellozzo, 2019). Law enforcement agencies are thus confronted with the dual challenge of not only keeping pace with the technological complexity of these offences but also addressing this as a growing problem, in turn increasing the need for recruitment and retention of investigators, something that has proved challenging (Riksrevisionen, 2021).

In the current state of research surrounding the policing of online CSA, three topics are prevalent. First, criminologically oriented research has engaged with issues of online CSA crimes looking at criminogenic factors associated with offenders (cf. Choi & Lee, 2023; Sinclair et al. 2015). Furthermore, since online CSA is a technologically oriented crime type, there is also research focusing on the need for technological and digital tools to be developed (Sunde & Sunde, 2022). Lastly, a dominant research theme on online CSA regards investigators’ well-being, as researchers have addressed themes such as the risks of moral injury (Leclerc et al., 2022), vicarious trauma (Burrus et al., 2017), and general risks of psychological harm for investigators (Strickland et al., 2023). While these topics are all central and important to consider in relation to online CSA investigation, an issue that hitherto has received less attention from research is the organizational processes that are involved in the investigation of online CSA, and specifically how collaboration between functions with different skillsets can be enhanced in this context.

In this article, we address this underexplored issue by examining how the investigative process of online CSA cases is structured and the challenges the investigators experience. We then move on to discuss the implication of these identified challenges for an effective organization of online CSA investigations. We aim to answer the following two research questions:

-

How do investigators describe the process of investigating online CSA crimes?

-

What challenges do they identify in relation to the investigative process?

2. The organizational dimension of online CSA investigation work

Although previous research on the organizational challenges and arrangements associated with online CSA is limited, two key themes can be identified: the importance of collaboration in CSA investigations, and the issue of occupational stigma. Studies addressing these themes are presented below.

2.1 Collaboration in online CSA investigations

A common denominator in the research that has targeted organizational dimensions of online CSA investigation is the need for multi-skilled, cross-functional teamwork in these settings. For instance, Wilson-Kovacs et al. (2022) examined the day-to-day organizational arrangements in which online CSA investigation takes place, and showed that collaboration between IT forensics, investigators, and managers was extensive. Profound forensic expertise combined with knowledge of investigating sexual offences against children are key success factors in online CSA investigations. Similar conclusions were drawn by Stol (2002), who also discussed the importance of collaboration between online CSA units, rank-and-file officers, as well as other investigative capacities, in order to sufficiently address cases with different complexity and workload.

While these researchers discuss collaboration from a perspective of how an efficient workflow can be achieved, another perspective on the importance of collaboration concerns how collaborative work processes enable a reciprocal form of emotional support within online CSA units (Tapson et al., 2022). Two studies by Powell et al. (2014a, 2014b) exemplify the degree to which teamwork was integral to investigators’ abilities to cope with various stressors in their work environment. In the studies, collaboration and interactions with colleagues within online CSA investigation was important for informal debriefing, social bonding, peer monitoring, and sharing of (often black) humour that provided relief in a work situation with enduring workplace stressors. While these examples are informal, a common feature of online CSA investigation work practice is also more formalized efforts to work with social support, such as peer support programmes, group counselling, and team building. In essence, research on this matter points to the conclusion that rich collegial relationships provide an important prerequisite and framework for effective coping.

The studies above point to the fact that there is potential for greater efficiency in the establishment of more systematic approaches to teamwork in online CSA investigation. This conclusion also seems to be true for other types of investigations. For instance, in their review of effective police investigative practices, Prince et al. (2021) linked higher case clearance rates to team-oriented investigative methods and collaboration between investigative units. Additionally, research on crime investigation work practices, as highlighted by Hällgren et al. (2021), has emphasized the importance of social and collective sensemaking derived from collaboration and knowledge integration, particularly when handling complex cases. Similar findings were reported in Brookman et al.’s (2019) study of homicide investigations, where bringing detectives with diverse skillsets together in teams and letting the team constellations develop as investigations unfolded was identified as a critical success factor. In other words, it is of great importance to integrate and combine competencies for efficient investigation work; in online CSA cases, this means combining expertise in technology and sexual offences against children in the investigations (Henry & Powell, 2018; Holt et al., 2020).

A final point regarding collaboration in online CSA investigation work concerns the importance of multi-agency collaboration, which is needed in cases that involve identified victims. In a study of ʻnetworked policing’ in a Canadian online CSA context, Grace et al. (2019, p. 198) discussed the potential benefits of a networked approach and proposed that when police and other agencies collaborate with mutual understandings and clear roles, this facilitates workflows that prioritize the safety and best interests of children. As indicated by Voss et al. (2018) and Newman et al. (2005), these kinds of multidisciplinary, child-friendly settings with representatives from various agencies can provide support and service to child victims, relatives and witnesses. From a police perspective, they are an important setting for conducting victim and forensic interviews.

2.2. The occupational stigma of online CSA investigations

As many of the studies above allude to, working as an online CSA investigator involves managing burdensome and emotionally challenging tasks, such as reviewing large amounts of disturbing image and film material and meeting young victims. In addition to the emotionally demanding investigations impacting investigators’ well-being and increasing work-related stress (Huey & Kalyal, 2017), working with issues considered taboo can also result in the investigators becoming “tainted” by and associated with the crimes they investigate. This can in turn lead to people distancing themselves from the CSA investigators, a phenomenon commonly referred to as “dirty work” when discussing stigma at an occupational level (Ashforth & Kreiner, 1999; Zhang et al., 2021).

Occupational stigma typically arises from having work tasks that are perceived as undesirable, unpleasant or morally questionable, leading to the attachment of stigma to those who undertake them. For example, Zilber (2002) suggests that workers in rape crisis centres are exposed to burdensome emotions when assisting victims, and thus coming into close contact with “dirty” and detestable crimes such as rape. More current research, conducted specifically in a context of online CSA investigation units, has also acknowledged how working with “virtual dirt”, such as child abuse material, fall into the same category (Wilson-Kovacs et al., 2022).

The effects of being stigmatized has been described as wide-ranging and complex, impacting various aspects of an individual’s well-being, from psychological and emotional health to social relationships and job satisfaction (Ashforth & Kreiner, 1999; Ruebottom & Toubiana, 2020). However, as noted by Zhang et al. (2021), there is limited research on how stigma affects the organization, but that it is reasonable to expect that organizations characterized by an occupational stigma would have reduced employee engagement and productivity, or high turnover rates – a pattern observed in online CSA units (Riksrevisionen, 2021).

3. Methods

This article is based on data collected within a broader collaborative intervention project on cross-functional teamwork in criminal investigations, and is conducted within one of Sweden’s seven police regions. As with many intervention projects, the initial phase of data collection was oriented towards mapping current challenges within the given practice (Meng et al., 2019). Thus, the data collection for this study was explorative in nature and aimed at describing the investigative process in case work as well as the central challenges experienced by the online CSA investigators in relation to their work practice.

3.1 Data collection

The data collection draws on a case study tradition (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007) in which criminal investigation can be seen as a specific work practice governed by rules, structures, beliefs, values, presuppositions that “go without saying”, and normative ideas that inform an agent’s actions. Thus, many qualitative methods can be used in tandem to examine what the main concerns of actors within such a practice revolve around and what behaviours are used to resolve such concerns (Artinian, 2009).

We have used several qualitative methods of data collection to map experiences of current work processes and challenges in online CSA investigations. More specifically, we have analysed documents (approx. 140 pages), conducted interviews with key stakeholders and strategic management in the police (n=3), sat in on five meetings with strategic management where online CSA was discussed, and organized a workshop with online CSA investigators (n=7) where the participants used graphic elicitation methods (Bravington & King, 2019) to describe a typical case process.

The data collection was conducted in two rounds. In the first round, we analysed the documents, interviews, and meeting observations that intended to give the research group an initial understanding of how online CSA investigations are organized in the Swedish police. Additionally, we aimed to identify the known challenges that different stakeholders within the police identify in relation to this branch of investigation.

The documents we analysed included two audit reports (one internal and one external) detailing the current organization and performance of online CSA investigation units within the Swedish police. Beyond the insights gained from these reports, we conducted three semi-structured interviews with managers of online CSA units. Furthermore, we sat in on and observed meetings where strategic management discussed the organization of online CSA investigations at a regional level.

Following this first round of data collection, we organized a three-hour workshop with participants directly involved in online CSA investigations (such as lead investigators, section heads, intelligence analysts and investigators) from different parts of the studied police region. The workshop aimed to collaboratively enhance the understanding of the work process of investigations by exploring the challenges of their operations. Seven participants took part in the workshop, and they were divided into two smaller focus groups. Their primary task was to elucidate the operational procedures in online CSA investigations. In this endeavour, we used graphic elicitation as a method (also called participant-led diagramming; Umoquit et al., 2011). In short, this method is participant-driven, and in our case, it entailed that the focus groups discussed the case process while also drawing it up as a timeline, flowchart or other type of process model of the participants’ choice.

During the process, the graphic representation facilitated the discussion of aspects such as the order of activities in case work, central problems, social nodes, connections (to others within and outside the police), and general experiences of the case process. Specifically, the participants were tasked with explaining the step-by-step process from a crime being reported to court hearing. In relation to this process, they were asked to reflect on their roles, the parties involved, necessary cooperation, parts of the process that usually work well, and where problems may arise. Following this, all participants reconvened as a larger group to present their process models and engage in a collective discussion.

The workshop concluded with an exercise where the participants generated a list of identified problems based on the process mappings. Throughout the workshop, all four authors were responsible for observing, discussing with participants, and taking notes to capture important insights. The workshop ended with a short survey-based workshop appraisal in which the participants were given the opportunity to anonymously comment on the methods and activities. Among other things, the informants were asked about the perceived relevance of the workshop content to their work. On a seven-degree scale (1 – not relevant at all, 7 – very relevant), the workshop was given a 6.1 mean average.

3.2 Analysis

The findings are based on an analysis of the audit reports, notes from the observed meetings, transcribed interviews with strategic management and flowcharts produced during the workshop. This data was compiled with the software NVivo 12 for processing. As the study aims to explore challenges in online CSA investigations, the analysis focused on identifying the main issues and commonalities as described by the informants. Thus, we conducted basic content analysis and constructed codes and categories in two steps.

First, we conducted what Strauss and Corbin (1998) refer to as “open coding”. That is, we compiled several first order codes that adhere to informant terms in the coding software. After going through the material in this way, we started to seek similarities and differences among the codes and thereby moved our analytical focus to what Miles et al. (2014) call “axial coding”, where we constructed fewer but more overarching themes to describe the central challenges related to the investigation of online CSA crimes.

During the whole process, we used the flowcharts from the workshop as a reference and as a guide to make sense of the narratives and themes that were articulated by the participants. By combining the descriptions of the online CSA units from the audit reports and the flowcharts drawn by the workshop participants, we were able to create a model illustrating a standard case process in online CSA investigation. Additionally, our analysis of the meeting observations and interviews with both strategic management and participants directly involved in online CSA investigation led us to the identify three main themes of challenges in the investigative process. These are “Assessing the magnitude of online CSA cases”, “Fear of contamination” and “Organizational compartmentalization”.

4. Findings

In the following section, a concept map of the online CSA investigation process in Sweden along with the three main themes of challenges that occurs in relation to the process will be presented. To ensure the anonymity of our participants, we have assigned them numerical identifiers. When citing their statements, these numbers will be indicated in parentheses. The findings include quotes from both workshop participants and strategic management interviewees. However, given the small number of individuals involved, we will not differentiate between these two groups in our citations.

4.1 Concept map of online CSA investigations in Sweden

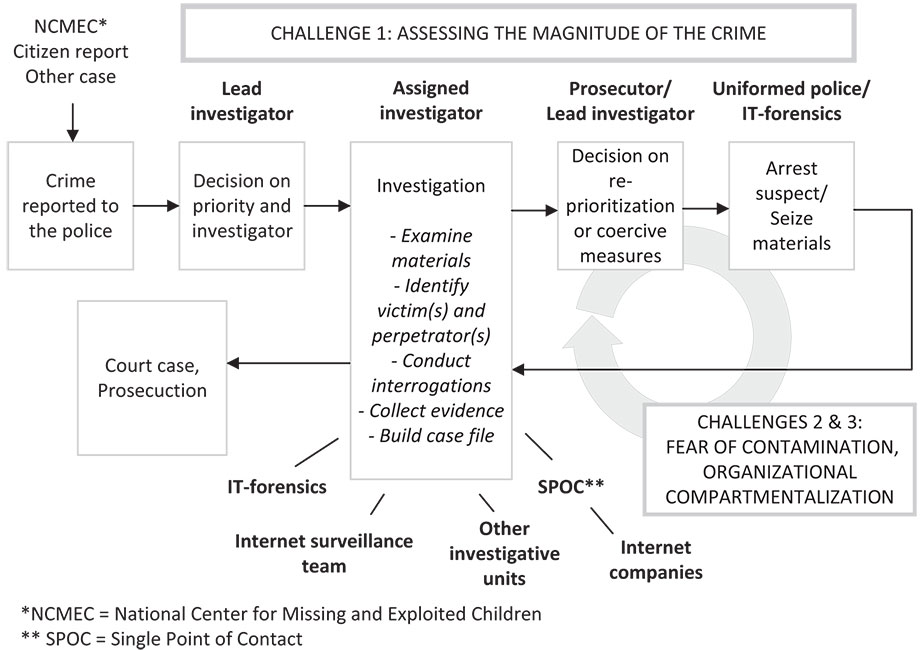

The nature of online CSA offences can be highly varied. This section describes a general process model of online CSA investigations in Sweden and is based on the models drawn by participants in the two focus groups (n=3 and n=4). The model below illustrates the workflow of a standard case process. The actors are marked with bold type while the processes are presented in boxes.

Figure 1

Workflow of a Standard Case Process in Online CSA Investigations

Typically, a case is reported in one of three ways: through the non-governmental organization National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC); an individual, such as a concerned parent, files a report; or it is discovered through another ongoing case.

The case is then assessed by the lead investigator working in the unit. Here, the order of priority is decided, and the case is assigned to an investigator. Based on the seriousness of the suspected crime, the lead investigator also decides whether the police can lead the investigation or whether a prosecutor will do so.

The investigator proceeds to investigate, based on the initial reports of the crime. One important but mentally taxing task is to examine the material. This can be documented abuse of a child or chat conversations between a child and the suspect. Here, the investigator determines whether a crime is committed, and if so, the seriousness of it. They then proceed to the possible identification of the victim(s) and perpetrator(s).

Depending on the findings at this initial stage, the investigator can recommend that a suspect is apprehended, that the computer and/or phone are taken for analysis, or that victim interviews and interrogations are held. Technical information may also be collected from IT companies. This is usually done by involving a centralized police function called SPOC (Single Point of Contact). These kinds of coercive measures need to be decided upon by a prosecutor or police lead investigator.

Once the material is secured, it needs to be analysed. At this stage, the investigator depends on the help of other departments and functions within the police. The main ones we identify as collaborative units are IT forensics (who e.g. break into a password-protected computer and copy all photo material), internet surveillance teams (who “patrol” the internet and social media and provide information based on open sources), other police departments (who are assigned as extra resources in large and complex cases) and internet providers (who can give information on their customers to the extent legally possible). Interviews with the victims, which require special training, and interviews with the perpetrators are also important investigative measures. Once the investigator has built a case with evidence, the case then proceeds to final serving, concluding with a decision to prosecute.

4.2 Challenges in the investigation process

We identify three main challenges in the online CSA investigation process. In Figure 1, these are shown to surface at different stages of the process. The first challenge – assessing the magnitude of online CSA crimes – concerns the initial steps. The second and third challenges – fear of contamination and organizational compartmentalization – primarily concern the investigative process and the collaboration with other units in the organization.

4.2.1 Assessing the magnitude of online CSA cases

The Swedish police adhere to a procedural approach that prioritizes the most serious crimes when it comes to setting priorities and allocating resources. However, when dealing with online CSA crimes, this approach has proved challenging to implement. This is because the extent of these crimes often remains undiscovered until the investigation has progressed quite far.

The investigators use the metaphor of a “fishing net” when discussing the process of determining the scope of the cases. This fishing net catches everything from small fish to large whales, and one does not know what is in it until well into the investigative process. The following example is an authentic case that was reported by the Swedish National Audit Office in their audit report of online CSA, highlighting the complexities of assessing the magnitude of a crime:

A mother discovers that her 10-year-old daughter has sent a bikini picture to an unknown man from her phone, and reports it to the police. The police then start a preliminary investigation, identify the man, and can then proceed to do a house search. Confiscated materials from the house search show that the man has been in contact with many girls, and that he is also working together with three other men. The case grows dramatically and suddenly includes approximately 1,500 criminal suspicions that result in prosecution for approximately 1,000 crimes. In total, the case involves around 45 plaintiffs who are 8–16 years old.

As this example illustrates, online CSA investigations have an unpredictable and expansive nature. The extent of the investigation can start with investigating a single sent picture, which is the initial information the police have access to as they allocate resources. However, this single picture might in an instance lead to the uncovering of a vast and complex case that requires substantial extra resources over different geographical (sometimes international) regions. Once the case is reprioritized as urgent and important, other cases must wait. This unpredictability constitutes a major difficulty for operations.

4.2.2 Fear of contamination

A recurring theme in the workshop, highlighted as one of the most significant challenges, revolves around the investigation process of online CSA cases being challenging because many people express concerns about being exposed to materials depicting abuse. This is mostly expressed by police colleagues. However, one of the workshop participants describes how the fear of being exposed to abusive materials extends beyond police officers; even the courts sometimes resist engaging with it.

Adding to this, in one of the observed meetings a participant described how the work of investigating online CSA is largely surrounded by taboo. In some cases, investigators can therefore feel uncomfortable volunteering to work in these investigation units, as well as giving support to them, as it can lead to suspicious questions from colleagues and others, along the lines of “why – do you like this?” (Participant 14). This leads to specific problems in online CSA operations, with a paramount challenge being that it hinders online CSA investigation units from assigning tasks to other departments and thereby decreasing their workload in the cases that do not require their special expertise.

Given that online CSA crimes often involve a substantial volume of material that requires review, the challenge of delegating to others results in a shortage of investigators who can carry out these work tasks. Consequently, all crimes, regardless of their scale, are handled by (over)qualified resources that end up scrutinizing cases of mass offences or “simple” matters rather than the more serious crimes for which they are qualified. This not only increases the workload for online CSA investigators but also leads to prolonged processing times. A participant in one of the observed meetings described how the fact that online CSA investigation teams handle all crimes regardless of their magnitude both results in an overexposure to abusive material and represents a misallocation of resources towards something that is not technically demanding, but is mentally taxing for those involved.

4.2.3 Organizational compartmentalization

During both the focus group sessions and the meeting observations, a consistent theme emerged that there is a certain mindset within the police organization in general that can especially hinder the investigation of online CSA crimes. In this mindset, people tend to see only “their” case or “their” department, and any work and collaboration expected to happen between different departments therefore risks encountering difficulties. One participant stated:

The major challenge for us is for people to see the bigger picture […]. For instance, people dealing with volume crime may say “Why should I work on child pornography offences? That’s not what I signed up for.” There is a mentality of focusing on “their” case or department rather than considering the overall perspective. (Participant 12)

Another participant added:

The culture is that you work within your department with your crimes; we are generally not good at working across borders. One must be able to lift one’s gaze, but there is still a long way to go. (Participant 13)

In addition to this mindset prevailing within the police, participants also described a typical mindset specifically related to online CSA investigations, regarding how the police authority acts differently in relation to these crimes compared to other crime types. The following comparison is made by an informant:

In all other police work, there is the attitude that “you have to do this, you just have to obey orders”, but here it’s different. Then suddenly, the police authority thinks it’s okay to say no. It would never be okay to choose not to go to, for example, a traffic crime with a fatal outcome, then it’s like, “just go”, but with online CSA crimes there is a greater acceptance of saying no. (Participant 1)

Similar to this, one participant described how other parts within the broader police organization can be characterized by a culture inclined to deflect problems and not see online CSA crimes as their responsibility. Commonly, the jurisdictional responsibility for crimes is based on a geographic principle, where the investigation should be conducted locally or as close as possible to the crime committed. In online CSA crimes, however, managers could express that they should not have the main responsibility, but rather “pitch in” or “help out in child pornography investigations” (Participant 14), even though the crime was committed locally. A common view here was thus that online CSA is not something the police on a broad scale would engage with, but rather only specialized online CSA investigators. While this distancing from online CSA investigations was common, the research participants also added that in more serious cases, it was easier to acquire assistance, as people in the organization recognized the severity of the crime.

5. Discussion

There is an ongoing need to identify and develop effective strategies for working with online CSA investigations (Sunde & Sunde, 2022). An important first step in developing such strategies is to thoroughly understand current work practices, as it is difficult to create effective solutions without this foundational knowledge. Our study contributes to this by detailing how investigators are organized and highlighting challenges faced by online CSA investigators in Sweden. In this section, we will discuss our main observations and interpret their implications for effective, collaborative online CSA investigations.

Like other research on online CSA (e.g., Powell et al., 2014a), our findings show how online CSA investigation builds on interdependencies between investigators and IT forensic experts, that these crimes can expand quickly, and that they regularly cut across jurisdictional as well as organizational and national borders (Europol, 2021). Furthermore, the investigative process is challenged by difficulties in assessing the magnitude of a crime initially and by time constraints as immense amounts of abusive material might need to be analysed, while investigations also need to be proceeded in a timely fashion (Henry & Powell, 2018). As we show in our analysis, these factors contribute to a variability and complexity in the investigative process that in turn makes the work challenging from the perspective of resource allocation. We also show that it is challenging for the police organization to determine the necessary competencies and to what extent they are needed in a timely manner. Regarding collaboration, the risk of cases quickly escalating also presents a challenge in structuring effective teams.

Our findings also indicated that a barrier to effective collaboration is the current concern within the broader facets of the police organization regarding the involvement in online CSA investigation. In short, there is a reluctance of non-specialized investigators to be associated with these crimes, and therefore, obtaining the necessary support becomes challenging for the investigators. This problem of not getting the proper support leads to overqualified investigators working with crimes that could have been handled with less specialized expertise (e.g. possession of a picture of sexual exploitation of a child) and, consequently, a formidable workload.

Another finding from our study concerns a longstanding culture of organizational compartmentalization that was described as hindering collaboration, as different branches of investigation remain separated. Since collaboration and knowledge integration between investigative units have been identified as crucial for managing complex cases (Hällgren et al., 2021) and have been associated with increased case clearance rates (Prince et al., 2021), it is concerning that the bureaucratic and legalistic traditions and structures within the police organization seem to be at odds with the extensive cross-functional collaborations that are essential for online CSA investigations.

5.1 Implications for working with online CSA crimes

While our findings highlight a number of challenges, they also indicate a broad agreement that collaborative approaches to online CSA investigation are a prerequisite for working with these cases in a change-oriented and agile way. This also echoes a broader institutional movement within police organizations: from an institutional perspective, teamwork has been highlighted as a strong driver of change and innovation, where traditional “compartmentalized” approaches to investigation are substituted for knowledge- and problem-based policing that builds on evaluation, fostering learning climates, and adopting innovation and knowledge (Andersson Arntén, 2013; Kihlberg & Rantatalo, 2022). In this light, the barriers to collaboration we identified on the local level of online CSA investigation can be concluded to be at odds with overall ambitions to become more problem-oriented and proactive on an organizational level, focusing on the root problems of this particular crime type rather than on reactive investigation and organizational issues (Weisburd et al., 2010). A key theme in the implementation of changes within online CSA investigation is thus to address why there seem to be prevailing obstacles to collaboration within this context.

The challenge concerning established structures and online CSA investigations also concerns how crimes are prioritized within the police. The police operate on a principle of prioritization where the more serious the crime, the more resources and urgency is attributed to investigations. However, some online CSA investigations, as shown, tend to grow exponentially after initial measures, meaning that the priority level changes as the investigation progresses. The seriousness of the crime is unknown from the outset – which complicates resource allocation, predictability, planning, and work with other cases. The definition of “seriousness” also seems to have a judgemental component. It is not decided based on resulting years in prison or clear-cut legal boundaries; in prioritizing cases, lead investigators must consider a range of aspects, such as the risk of repeat offences, access to children, and so on. A widespread feeling that child sexual exploitation in itself is particularly serious and ruthless probably affects the working priorities for investigators and the police as a whole.

Finally, a recurring theme emerging from discussions with the participants is the reluctance within the police organization at large to engage in investigations of online CSA crimes, and how abstaining from them seems to be widely accepted. In our findings, we categorize these narratives into two distinct aspects: “fear of contamination” and “organizational compartmentalization”. However, these findings could also be interpreted as an implication of online CSA work being stigmatized in the police organization. The problems with being a stigmatized or “dirty” worker has been described as affecting various aspects of an individual’s well-being, from psychological and emotional health to social relationships and job satisfaction (Ashforth & Kreiner, 1999; Ruebottom & Toubiana, 2020). Further, previous research has established that investigating cases of child sexual abuse is challenging and involves exposure to potentially traumatic material or information (Henry & Powell, 2018), something that impacts investigators’ well-being and increasing work-related stress (Huey & Kalyal, 2017).

In this article, we show that stigma acts as a barrier to collaboration within the organization. Our findings thus contribute to the literature on dirty work by revealing how engagement in tasks surrounded by an occupational stigma can influence social interactions within the organization, thereby negatively affecting the potential for effective collaboration across functions and units. Organizational stigma and isolation is a relatively unexplored area, and in the context of online CSA investigation it is essential to examine this issue more thoroughly. This article is a start for making this phenomenon more visible, which is the first step in mitigating its effects. As our analysis of the audit reports shows that online CSA units have difficulties with recruiting and high turnover rates, aligning with Zhang et al.’s (2021) findings on how stigma impacts organizations, exploring this stigma more deeply could thus improve retention and recruitment of investigators.

As mentioned, a dominant stream of previous research has voiced concern about the well-being of these investigators. It has hitherto been assumed that exposure to disturbing material and vulnerable and innocent victims are causing adverse mental health effects. However, based on our findings, we would also suggest that the impact of organizational stigma might be a contributing factor to the well-being of these investigators. We know that stigmatization causes individuals to feel different, isolated, and misperceived by others, leading to general avoidance (Huey & Kalyal, 2017). Even if someone finds investigative work intriguing and important, the investigators and other important instances such as IT forensics must deal with the distancing of others (Wilson-Kovacs et al., 2022). Considering the broad agreement today that being valued, seen, and heard at work contributes to employee well-being in a range of contexts, we can also establish that the absence of these factors can lead to various negative outcomes. This all points to the need for increased attention to and management of the stigmatization connected to online CSA investigation.

5.2 Limitations and suggestions for further research

While this study is explorative and aims to provide insights into the organization and challenges of online CSA investigations within the Swedish police, it is important to recognize the limitations inherent in a qualitative study with a small sample. The insights from our participants offer a snapshot of the current situation, but may not represent the broader experiences of all investigators working on online CSA cases, both in the rest of Sweden and internationally. Further research is needed to examine how these findings translate to other contexts and to identify potential variations in investigative practices and challenges. Further studies with larger sample sizes and more diverse participant pools could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the issues faced by investigators across different regions and jurisdictions.

Future research could also explore longitudinal designs to understand how the evolving technological landscape affects the dynamics of online CSA investigations over time. Given the rapidly changing nature of CSA methods and technology (Europol, 2021; Sunde & Sunde, 2022), it would be valuable to track how investigative strategies are adapted to these developments and whether the same challenges persist or change over time. Another area for further research involves investigating how the stigma surrounding CSA investigations manifests and impacts investigators. Additionally, exploring the underlying reasons for the reluctance to engage in online CSA investigations and the factors contributing to the acceptance of abstaining from such work would be beneficial.

Lastly, the identified challenges related to organizational compartmentalization suggest a need for studies focusing on cross-functional collaboration within police organizations. Understanding how bureaucratic structures can be reimagined to promote better integration and teamwork across investigative units could lead to a more efficient and effective handling of complex online CSA cases. Interventions where models of cross-functional teamwork are evaluated would be a particularly promising future direction for research. Addressing these issues can lead to a more effective and supportive environment for investigators, ultimately contributing to more successful outcomes in combating online CSA crimes.

6. Conclusion

This study sheds light on the complexities and challenges associated with online child sexual abuse investigations within the Swedish police. Through document analysis, meeting observations, interviews, and a workshop with CSA investigators, we have identified key challenges investigators face, including the difficulty of assessing the magnitude of these crimes, the stigmatization involved, and the struggle to allocate resources efficiently. Moreover, the structural and cultural issues within the police organization, such as compartmentalization and a lack of cross-functional collaboration, further complicate the investigative process.

Our findings highlight the need for effective strategies to address these challenges. Given the rapidly evolving nature of online CSA crimes, police departments must remain adaptable and open to new investigative techniques. The study also underscores the importance of providing adequate support for investigators, recognizing that exposure to CSA cases can be deeply distressing. The insights gained from this study point towards several avenues for future research, including studies with broader and more diverse samples, longitudinal studies to track changes over time, and investigations into organizational culture and its impact on teamwork and collaboration.

Funding

FORTE (Forskningsrådet för hälsa, arbetsliv och välfärd). Grant number: STY-2023/0004

References

-

Andersson Arntén, A.-C.(2013).

Är polisen en lärande organisation? En intervjustudie om polisens ledningsstruktur

. [Is the police a learning organization? An interview study about the police’s leadership structure].Rikspolisstyrelsens utvärderingsfunktion

. -

Artinian, B. M.(2009). An overview of Glaserian grounded theory. InB. M. Artinian,T. Giske, &P. Cone(Eds.),

Glaserian grounded theory in nursing research

(pp. 3–18).Springer

. -

Ashforth, B. E., &Kreiner, G. E.(1999). “How can you do it?”: Dirty work and the challenge of constructing a positive identity.

Academy of Management Review

, 24(3), 413–434. -

Bravington, A., &King, N.(2019). Putting graphic elicitation into practice: Tools and typologies for the use of participant-led diagrams in qualitative research interviews.

Qualitative Research

, 19(5), 506–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794118781718 -

Brookman, F.,Maguire, E. R., &Maguire, M.(2019). What factors influence whether homicide cases are solved? Insights from qualitative research with detectives in Great Britain and the United States.

Homicide Studies

, 23(2), 145–174. -

Burruss, G.,Holt, T., &Wall-Parker, A.(2017). The Hazards of Investigating Internet Crimes Against Children: Digital Evidence Handlers’ Experiences with Vicarious Trauma and Coping Behaviors.

American Journal of Criminal Justice

, 43, 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-017-9417-3 -

Choi, K. S., &Lee, H.(2023). The trend of online child sexual abuse and exploitations: A profile of online sexual offenders and criminal justice response.

Journal of child sexual abuse

, 1–20.Advance online publication

. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2023.2214540 -

Eisenhardt, K. M., &Graebner, M. E.(2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges.

Academy of Management Journal

, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2007.24160888 -

Europol. (2021).

The cyber blue line

.Europol. Publications Office of the European Union

. https://www.europol.europa.eu -

Grace, A.,Ricciardelli, R.,Spencer, D., &Ballucci, D.(2019). Collaborative policing: networked responses to child victims of sex crimes.

Child Abuse & Neglect

, 93, 197–207. -

Hällgren, M.,Lindberg, O., &Rantatalo, O.(2021). Sensemaking in detective work: The social nature of crime investigation.

International Journal of Police Science & Management

, 23(2), 119–132. -

Henry, N., &Powell, A.(2018). Technology-facilitated sexual violence: A literature review of empirical research.

Trauma Violence Abuse

, 19(2), 195–208. -

Holt, T. J.,Cale, J.,Leclerc, B., &Drew, J.(2020). Assessing the challenges affecting the investigative methods to combat online child exploitation material offenses.

Aggression and Violent Behavior

, 55, 101464-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101464 -

Huey, L., &Kalyal, H.(2017). We deal with human beings: The emotional labor aspects of criminal investigation.

International Journal of Police Science & Management

, 19(3), 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355717717996 -

Internet Watch Foundation. (2023).

How AI is being abused to create child sexual abuse imagery

. https://www.iwf.org.uk/media/q4zll2ya/iwf-ai-csam-report_public-oct23v1.pdf -

Kihlberg, R., &Rantatalo, O.(2022). Motivating police reform through multimodal sensegiving: How change was promoted through videos in the Swedish police reorganisation.

Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing

, 9(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.18261/NJSP.9.1.2 -

Leclerc, B.,Cale, J.,Holt, T., &Drew, J.(2022). Child sexual abuse material online: The perspective of online investigators on training and support.

Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice

, 16(4), 762–776. -

Martellozzo, E.(2015). Policing online child sexual abuse – The British experience.

European Journal of Policing Studies

, 3(1), 32–52. -

Martellozzo, E.(2019). Online child sexual abuse. InY. Robinson&W.A. Petherick(Eds.),

Child abuse and neglect: Forensic issues in evidence, impact and management

, 63–77.Academic Press

. -

Meng, A.,Borg, V., &Clausen, T.(2019). Enhancing the social capital in industrial workplaces: Developing workplace interventions using intervention mapping.

Evaluation and Program Planning

, 72, 227–236. -

Miles, M. B.,Huberman, A. M., &Saldaña, J.(2014).

A methods source book: Qualitative data analysis

.Sage Publications

. -

Newman, B. S.,Dannenfelser, P. L., &Pendleton, D.(2005). Child abuse investigations: Reasons for using child advocacy centers and suggestions for improvement.

Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal

, 22, 165–181. -

Powell, M.,Cassematis, P.,Benson, M.,Smallbone, S., &Wortley, R.(2014a). Police officers’ strategies for coping with the stress of investigating Internet child exploitation.

Traumatology: An International Journal

, 20(1), 32–42. -

Powell, M.,Cassematis, P.,Benson, M.,Smallbone, S., &Wortley, R.(2014b). Police officers’ perceptions of the challenges involved in Internet Child Exploitation investigation.

Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management

, 37(3), 543–557. -

Prince, H.,Lum, C., &Koper, C. S.(2021). Effective police investigative practices: An evidence-assessment of the research.

Policing: An International Journal

, 44(4), 683–707. -

Riksrevisionen. (2021).

Internetrelaterade sexuella övergrepp mot barn – stora utmaningar för polis och åklagare

[Internet-related sexual abuse of children – major challenges for the police and prosecutors].Riksrevisionen

. -

Ruebottom, T., &Toubiana, M.(2020). Constraints and opportunities of stigma: Entrepreneurial emancipation in the sex industry.

Academy of Management Journal

, 64(4). https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.1166 -

Sinclair, R.,Duval, K., &Fox, E.(2015). Strengthening Canadian law enforcement and academic partnerships in the area of online child sexual exploitation: The identification of shared research directions.

Child & Youth Services

, 36(4), 345–364. -

Stol, W. P.(2002). Policing child pornography on the internet—In the Netherlands.

The Police Journal

, 75(1), 45–55. -

Strauss, A., &Corbin, J.(1998).

Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory

(2nd ed.).Sage Publications

. -

Strickland, C.,Kloess, J. A., &Larkin, M.(2023). An exploration of the personal experiences of digital forensics analysts who work with child sexual abuse material on a daily basis: “you cannot unsee the darker side of life”.

Frontiers in Psychology

, 14, 1–10. -

Sunde, N., &Sunde, I. M.(2022). Conceptualizing an AI-based police robot for preventing online child sexual exploitation and abuse: Part 1 – The theoretical and technical foundations for PrevBOT.

Nordic Journal of Studies in Policing

, 8(2), 1–21. -

Swedish Police Authority. (2022).

Granskning av Polisens arbete avseende sexualbrott mot barn. Revisionsrapport

[Review of the police’s work regarding sexual crimes against children. Audit report].Polismyndigheten

. -

Tapson, K.,Doyle, M.,Karagiannopoulos, V., &Lee, P.(2022). Understanding moral injury and belief change in the experiences of police online child sex crime investigators: An interpretative phenomenological analysis.

Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology

, 37(3), 637–649. -

Umoquit, M. J.,Tso, P.,Burchett, H. E. D., &Dobrow, M. J.(2011). A multidisciplinary systematic review of the use of diagrams as a means of collecting data from research subjects: Application, benefits and recommendations.

BMC Medical Research Methodology

, 11(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-11 -

Voss, L.,Rushforth, H., &Powell, C.(2018). Multiagency response to childhood sexual abuse: A case study that explores the role of a specialist centre.

Child Abuse Review

, 27(3), 209-222. -

Weisburd, D.,Telep, C. W.,Hinkle, J. C., &Eck, J. E.(2010). Is problem-oriented policing effective in reducing crime and disorder?.

Criminology & Public Policy

, 9(1), 139–172. -

Whelan, C., &Harkin, D.(2021). Civilianising specialist units: Reflections on the policing of cyber-crime.

Criminology & Criminal Justice

, 21(4), 529–546. -

Wilson-Kovacs, D.,Rappert, B., &Redfern, L.(2022). Dirty work? Policing online indecency in digital forensics.

The British Journal of Criminology

, 62(1), 106–123. -

Zhang, R.,Wang, M. S.,Toubiana, M., &Greenwood, R.(2021). Stigma beyond levels: Advancing research on stigmatization.

The Academy of Management Annals

, 15(1), 188–222. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2019.0031 -

Zilber, T. B.(2002). Institutionalization as an interplay between actions, meanings, and actors: The case of a rape crisis center in Israel.

Academy of Management Journal

, 45(1), 234–254.