Security Governance – An Empirical Analysis of the Norwegian Context

Martin Nøkleberg

PhD candidate at University of Oslo, email: Martin.Nokleberg@jus.uio.no

Publisert 13.05.2016, Nordisk politiforskning 2016/1, Årgang 3, side 53-82

This article explores the local security governance in the city of Bergen, and it thus highlights what characterizes security governance within a Norwegian context. The burgeoning policing literature suggests that we live in a pluralized and networked society – ideas of cooperation have thus been perceived as important features for the effectiveness in security governance. Cooperative relations between public and private actors are the main focus of this article and such arrangements are empirically explored in the city of Bergen. These relations are explored on the basis of the theoretical framework state anchored pluralism and nodal governance. The key finding is that there seems to be an unfulfilled potential in the security governance in Bergen. The public police have difficulties with cooperating with and exploiting the potential possessed by the private security industry. It is suggested that these difficulties are related to a mentality problem within the police institution, derived from nodal governance, that is, the police are influenced by a punishment mentality and view themselves as the only possible actor which can and should maintain the security.

Keywords

- security governance

- pluralization

- cooperation and partnership

- public police

- private security

- Norway

Introduction

Since the mid-twentieth century, the field of security governance has been characterized by changes and transformations. Once the monopoly of the state, the governance of security around the world is now characterized by plurality (Crawford, Lister, Blackburn, & Burnett, 2005; Johnston & Shearing, 2003). State and non-state, commercial and non-commercial actors operate alongside each other in the production and delivery of security. This has led policing scholars to speak about network and partnerships (Dupont, 2004; 2006a; Dupont & Wood, 2007; Fleming & Rhodes, 2005) between actors in order to enhance efficiency in the security governance. Internationally, the polycentric and networked security governance has in recent years received a substantial amount of scholarly attention. Thus, a range of national contexts have been explored and examined empirically (e.g. Australia, South Africa, the Netherlands, and Britain), which has resulted in important knowledge about different systems of security governance (see for instance Dupont, 2006b; Froestad, 2013; Marks & Goldsmith, 2006; van Steden, Wood, Shearing, & Boutellier, 2013; Wakefield, 2003). The Norwegian context of pluralized security governance, however, has not received as much empirical attention as the international sphere (see Larsson & Gundhus, 2007; Lomell, 2007; Myhrer, 2011 for some notable exceptions). But these studies do not examine polycentric and networked security governance in detail. Accordingly, it can be argued that there is a need for more empirical studies of the Norwegian context. One of the main purposes of this article is therefore to contribute with an empirical analysis which enhances the understanding of security governance within this context.

In this article, I examine the governance of security in Norway, and the question I address is what characterizes security governance in this Norwegian context? In order to highlight the question I have conducted a case study of local security governance in the city of Bergen. The first section is concerned with the contextual and theoretical foundation of the article. The focus is on a brief description of the development of the pluralized security governance, and the concepts of nodal governance and state anchored pluralism are elaborated. This is followed by methodological consideration in relation to the case study. In the main part of the article, the attention is turned towards the empirical investigation of Norwegian security governance. I have made a descriptive account in which my emphasis is at the business of different actors involved in the production and delivery of security in Bergen. One guiding question within this part has been; how do the public and the private actors work with security in relation to crime? This examination is then followed by an assessment of the collaboration and establishment of partnerships between state and non-state actors.

Changes in security governance – From a dream of state monopoly to pluralization

Security governance consists of two distinct concepts, security and governance. These two concepts will in the following be shortly elaborated. Within the field of criminology the distinction between objective and subjective security is highlighted as significant (Aas, Strype, Bjørgo, & Runhovde, 2010; Egge, Berg, & Johansen, 2010; Johnston & Shearing, 2003; Zedner, 2003, 2009). The distinction thus serves as the point of departure in this article. Therefore, when I speak about security, it refers to the objective state of being without, or being protected against threats, and it is used to describe the subjective state of freedom from anxiety derived from threats. Furthermore, it is crime that is considered to be the threat against security; that is what Baker (2010) consider to be «personal or citizen security». It is emphasized that the subjective condition of security is as important to most of us as any objective state of security (Johnston & Shearing, 2003). Thus, in order to effectively govern security, measures must both meet the subjective perception as well as the objective threats to security. The second concept, governance, is understood rather broadly as the «intentional activities designed to shape the flow of events» (Wood & Shearing, 2007, p. 6). Put together, security governance refers to «programmes for promoting peace in the face of threats (either realized or anticipated) that arise from collective life rather than from non-human sources such as the weather or threats from other species.» (Johnston & Shearing, 2003, p. 9).

During the last decades, one can identify significant changes and transformations concerning all spheres of governance (Burris, Kempa, & Shearing, 2008; Kersbergen & Waarden, 2004), as traditional mechanisms of governance have been challenged and new arrangements have emerged. In the context of security governance, which is the task of this article, profound changes have also occurred. Within traditionally conceptions of governance – e.g. the Hobbesian ideal – governance was perceived as the prerogative of the state (government) (Burris, 2004), and it was seen as a top-down affair. According to Wood and Shearing (2007, p. 8) this concept of governance can be characterized as state-centered involving the paradigm of «governance through force». Therefore, within this Hobbesian understanding the dream of the state was to effectively monopolize the field of security governance (Bayley & Shearing, 1996; Shearing, 2008; Shearing & Marks, 2011). Furthermore, it was the use of legitimate force to establish and maintain order that was sought monopolized. Weber (1946) followed up Hobbes’ line of thought when he defined states in terms of a legitimate monopoly over use of physical force to impose social order within its spatial boundaries. What is important to note here is that this monopoly has been vested – at least in terms of internal threats to security – within the police institution. The establishment of the London Metropolitan Police or the «new police» in 1829 by Sir Robert Peel is often viewed as a crucial step towards the realization of this state monopoly over security governance. Throughout the years since the inception of the new police it is argued that the police have done very well in realizing their dream. Indeed, so well that policing/security governance became synonymous with what police did. Shearing (2008), for instance, borrows Nils Christie’s phrase when he describes how well the police have done; the police now «owned» policing. Thus, security provision from the nineteenth and through the second quarter of the twentieth century was successfully monopolized by the police, inspired by a Hobbesian ideal of state sovereignty (Froestad, 2013; Wood & Shearing, 2007).

This view, however, has been challenged. One can no longer conceive of the state and their police as the monopolist of security governance. Now, in most modern societies, a whole range of non-state actors has undertaken the tasks of governance. Thus, state and non-state, commercial and non-commercial actors operate alongside each other in the production and delivery of security. Bayley and Shearing (2001) argue that those who authorize policing (auspices) and those who are conducting policing (providers) are now being separated from each other. And more importantly, both of these functions have increasingly been taking place away from the governmental domain. This, however, is not to say that states no longer are important actors of governance, as Shearing and Wood (2003, p. 405) point out, «at certain times and places state governments are empirically significant and powerful». Rather, it is suggested that the Hobbesian idea of a state sovereignty can no longer be perceived as true (see Foucault, 1990; Rhodes, 1997; Wood & Shearing, 2007). Loader (2000) put forth a similar point when he notes that the changes can be characterized as a shift from the police to policing. As a result of the restructuring within the security field, one can argue that the world of security governance is now being viewed and characterized as polycentric and fluid (Bayley & Shearing, 1996, 2001; Crawford et al., 2005; Johnston & Shearing, 2003; McGinnis, 1999; Wood & Dupont, 2006b), consisting of multiple actors operating alongside each other under the operations of governance.

Regarding the pluralization one important question arises; what can explain the expansion of the policing sphere? Within the policing literature, a range of possible answers has been highlighted. Jones and Newburn (1998), for instance, emphasize two sets of explanations; fiscal constraint theory and structuralist theory. The first is related to the assumption that the state has limited resources at its disposal, thus the police are experiencing fiscal restrictions leading to an increase in other policing actors. A further refinement of this argument can be linked to neo-liberal thoughts, that is, a number of governmental functions are being outsourced to non-state actors (Johnston, 2006; Johnston & Shearing, 2003). In terms of policing, neo-liberal thoughts have led to an outsourcing of some peripheral security tasks to non-state actors, and at the same time core functions have remained with the public police. The structuralist explanation is fully elaborated by Shearing and Stenning (1981) and their argument is concerned with the establishment of «mass private property». They argue that when one see changes or shifts in property relationships towards the notion of mass private property, one also finds a shift in the policing arrangement – from public to private policing. Myhrer (2011) points to another cause; he argues that the need or demand for security provision (mainly private provision) has been greater than the modern police have been able and willing to offer. These explanations of the pluralization seem all to be plausible. However, I would argue that the pluralization cannot be explained by one factor alone; it is rather a combination of factors that have led to the expansion of security governance.

As a consequence of the transformations within the policing realm, it is argued that one can identify a decoupling of the police and the state, and more importantly, questions concerning the implications of such a progressive decoupling have been raised (Loader & Walker, 2001). During the nineteenth and part of the twentieth centuries, policing was pursued in the name of a collective or public interest. Accordingly, the development of the modern police was influenced by a principle of publicness. The expansion of the security provision, however, may have challenged this view of policing as a public good. Loader and Walker (2001, 2006, 2007), however, have been occupied with this question throughout a series of works, and they argue that a positive connection between policing and the state can be formulated under contemporary conditions, and their argument is related to the publicness of the good of security. Their argument will be further elaborated below. Another aspect of the decoupling is related to how one frames the relationship between the state and the police and between state and non-state actors. It is argued that the relationships should be viewed as an open empirical question, rather than one that is decided a priori. Thus, by framing this empirical approach, one is open to the idea that important policing actors can arise from all spheres. Furthermore, it becomes possible to conduct a comprehensive (empirical) mapping of actors involved in the security governance.

Nodal governance and state anchored pluralism

The changing patterns of security provision have led scholars to characterize this provision in many western societies as increasingly complex (see Johnston & Shearing, 2003). In addition, one can identify an ongoing theoretical and normative debate between policing scholars about how to govern security in a mixed market of public and private provision. It seems that most scholars agree that pluralism is a general trend (Wood & Dupont, 2006a). But what differs is the ways in which they explain and describe this plurality. Hence, different theoretical frameworks for capturing the conditions for effective and democratic security governance in pluralized and networked societies are presented.

Shearing and colleagues present a «nodal governance» approach as a way of capturing the plurality (Burris, 2004; Burris, Drahos, & Shearing, 2005; Johnston & Shearing, 2003; Shearing, 2006; Shearing & Wood, 2003; Wood & Dupont, 2006b; Wood & Shearing, 2007). Nodal governance scholars argue that one must move away from a state-centered view in order to better understand the pluralized security governance. Thus, within a nodal perspective, no set of actors is given conceptual priority (Johnston & Shearing, 2003). This means that the exact composition and contribution of different nodes or actors should be an empirically open question and not decided a priori. The nodal approach places emphasis on the relationships and linkages between nodes. Networks are, as such, of central importance to the approach. Castells (1998, p. 332) argues that «A network, by definition, has nodes, not a centre». Scholars of nodal governance use this definition of network to focus on the nodes themselves in order to enrich the network theory; «nodal governance is intended to enrich network theory by focusing attention on and bringing more clarity to the internal characteristics of nodes (…).» (Burris, 2004, p. 341). Hence, the approach places its emphasis on the characteristics of nodes rather than on the networks themselves. In the nodal perspective, a node is conceived as «a site of governance exhibiting four essential characteristics» (Burris, 2004, p. 341). First, a mentality refers to a mental framework that shapes the ways we think about the world and the way we decide to act. In terms of the nodal approach a mentality, then, refers to the ways of thinking about the matters and issues that the node has emerged to govern (Burris et al., 2005). Within the security literature, two particular mentalities are highlighted as important – a punishment mentality and a risk mentality (Johnston and Shearing 2003). The first is concerned with reactive strategies based on punishment, reaction and retribution in relation to the wrongdoing (crime), and is connected to the criminal justice system. The latter one, Johnston and Shearing (2003, p. 16, see also Shearing, 2001; Shearing & Johnston, 2005) argue, is connected to pro-active strategies based on a chain of risk, anticipation, and prevention. This risk-based mentality is oriented towards the prevention of problems in the future. Central elements in this future-focused logic are instrumental calculations and techniques intended to reduce crime, danger and risk. In addition, emphasis is placed on the sources of opportunity for the crime to happen rather than on the wrongdoing itself. Second, technologies refer to the set of methods used for exerting influence over the course of events. Third, the implementation of technologies depends in large part upon nodes resources. Hence, resources will affect nodes capacity to exert influence over the course of events. And fourth, a node needs an institutional structure that enables the directed mobilization of resources, mentalities and technologies over time (Burris, 2004; Burris et al., 2005). Since not all nodes are created equal, nodes will therefore vary in their accessibility and their efficacy.

Another position on how to govern security in a world of public and private provision is introduced by Loader and Walker (2006, 2007). Loader and Walker’s position is based upon an idea of security as a «thick public good». Policing has long been characterized as a public good and the ideal has been that there should be universal equity in distribution and provision of this good, that is, security is equally available to all. As highlighted above, changes in the security governance may have challenge this notion of security as a public good. Still, Loader and Walker argue for an understanding of security as a public good. Their argument can be summed up in three dimensions. First, the instrumental dimension of security is concerned with «the sense in which security is seen as prerequisite to the effective liberty of individuals, which in turn is seen as prerequisite to the «good life», however conceived.» (Loader & Walker, 2006, p. 184). This means that security is perceived as a foundational element in the realization of freedom. However, the dimension is situated at the thinnest level. In order to perceive security as a «thick» public good, Loader and Walker argue that one has to move to a thicker level. The second dimension, called the social, is concerned with the notion that security of one individual depends in some distinct manner upon the security of others. Thus, Loader and Walker (2007, p. 161) suggest «That there is a tendency for the quality of security, (…), to be enhanced in the case of any particular individual when the security of those with whom that individual shares a social environment is also reasonably attended to». And more importantly, a system of public provision to guarantee this is considered to be one possible solution. At the thickest level one find the third, called the constitutive dimension of security. What Loader and Walker (2007, p. 162) are concerned with here is how security as a social good «is implicated in the very process of constituting the ‘social’ or the ‘public’». Thus, Loader and Walker (2007) argue that it is only when appreciating these dimensions of security one is capable of understanding the state’s implication in the production of security. Furthermore, they argue that security conceived as a «thick public good» is attainable only if one is able or willing to departure from an a priori state skepticism. In order for collective security to become possible and to be perceived as a public good, the state must be perceived as the main anchor in its provision. Hence, Loader and Walker introduce the concept of state-anchored pluralism, «The state (…) should remain the anchor of collective security provision, but there should be as much pluralism as possible both, internally, (…), and externally.» (Loader & Walker, 2007, p. 193). In terms of external pluralism, Loader and Walker argue, one has to recognize the appropriate place of other sites of cultural and regulatory production above, below and otherwise beyond the state. In this dimension the role of the state, they argue, should be as a meta-regulator. Marks and Goldsmith (2006) follow a similar line of thought as they maintain that the state must strengthen and reaffirm its primacy in the provision of security. Marks and Goldsmith’s argument is based upon the need to improve security for those citizens who are socio-economically disadvantaged and who reside in communities where the informal social control is weak. In their view the state is best placed in terms of capacity, legitimacy and effectiveness to provide equitable policing services for everyone. Thus, Marks and Goldsmith agree with Loader and Walker upon the idea that state should assert itself as the anchor of collective security provision, though at the same time be open to as much pluralism as possible.

There are clearly some differences between the «nodal approach» and the «state anchored pluralism». Nevertheless, both positions – though in different manners – accept the concept of pluralism in security governance. However, one can argue that some scholars are more concerned with the anchor than they are with pluralism and vice versa. According to Dupont and Wood (2006), anchoring comes in many forms. Their view is based on an idea that national context is a decisive factor for the anchoring project. In the context of Argentina, for instance, the anchoring project is a focus for human rights NGOs rather than state institutions (Wood & Font, 2004). But in contexts where states are viewed as «strong» – such as the Norwegian context this article interrogates – the anchoring project may differ, and more emphasis is often placed on the anchoring within the state.

The theoretical framework that has inspired this article – and thus serves as a point of departure – is the concept of state-anchored pluralism. Regarding this approach, it is important to highlight that there seems to be a lack of empirical analyses which examine the conditions for how such a system would function as a good output-producing system in different contexts. This lack of empirical examination gives rise to an important question; what are the conditions of state-anchored pluralism? As viewed above, the objective of Loader and Walker is primarily to defend the concept of state-anchored pluralism rather than to explore the conditions empirically. Hence, this article seeks to make an empirical contribution to the theoretical framework of state-anchored pluralism. However, elements from Shearing and colleagues’ framework are also of great relevance to the empirical analysis conducted here, in particular the notion of underlying mentalities found in the different actors.

Methodology

The empirical analysis is based on a case study of the local security governance in the city of Bergen, Norway. The data collection builds on a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. Further, the study was designed to identify important agencies involved in the production of security in Bergen and to map the relationships between them. In this study, the main sources of data have been derived from qualitative interviews and a survey, but documental analysis has functioned as a complement. In the period from September 2013 to February 2014, 14 interviews were conducted with key respondents belonging to 6 different organizations involved in the governance of security in the city center of Bergen. Interviews were conducted with representatives of state and non-state organization, and commercial as well as non-profit organizations. Some of these organizations had security as their primary concern – such as the police and private security companies – whilst others saw security as one concern among many others. All of the organizations, however, had experiences and knowledge that informed the research question. Interviews were semi-structured following a general interview guide; however, questions were tailored to the specific interviewee. In addition, follow-up questions on themes that emerged in the course of the interviews were also present. Interviews lasted from 30 minutes to 1.5 hours. During the interviews, a range of themes were covered, such as the specific involvement in the production and delivery of security (e.g. what activities are you intended to maintain, how do you go about these activities); perception of security issues in Bergen and how to solve them; and cooperation and relationships with other actors. Thus, the interviews generated a great deal of data about how the different actors worked with and thought about crime and security. The interviews also revealed much about the collaboration these actors were involved in. One guiding principle for the analysis of interview data was derived from the nodal governance approach, that is, the four characteristics depicted above were used in order to structure the data.

During the same period as the interviews, a questionnaire (survey) was sent out to 32 organizations in order to capture ties or partnerships which these organizations maintained. The data on the security network in this article is derived from this survey. These 32 organizations had in common that their main task or part of their main task was the production and/or delivery of security for the benefits of individuals or other organizations in the municipality of Bergen. Relevant entities were identified through membership lists of professional security associations, the registration data of the police who regulate the security industry, internet searches, and snowball sampling during the qualitative interviews. Thus, an exhaustive list of actors involved in the governance of security in Bergen was produced. Representatives were asked to name organizations with which partnerships – both formal and informal – had been maintained over the past twelve months. The methodological framework for mapping the security network draws inspiration from Dupont’s (2006a) considerations on how to map and model complex organizational sets. These two methods of data collection – interviews and survey – were complemented with a documental analysis. During the data collection, documents from different sources were collected, such as governmental documents, internal documents from organizations, and newspapers. The various methods used in the study served different purposes, but altogether they enabled a comprehensive assessment of the security governance in Bergen and the actors involved.

The municipality and the public police – guarantors of public security

In the framework of state-anchored pluralism elaborated above, it is expected that the state undertake the role as a guarantor of public goods, and in particular, public security. It can be argued that this idea is based on values derived from the rule of law, where the police and criminal justice system are seen as important institutions for citizens’ overall safety. In many parts of the world, however, it is not necessarily clear that the state and the public police undertake such a role – as guarantors of public goods. The reason can be ascribed to the constant threat of corruption and exploitation of public office – which is a feature of governance in a range of countries across the globe. Corruption, it is argued, may undermine good governance and the rule of law, and thus poses threats to the principles of democracy and justice (Graycar & Sidebottom, 2012). In addition, it has been argued above that the relationship between the police and state should be framed as an empirical question. Thus, it is of importance to examine how the municipality of Bergen and the public police perceive their role in society and in particular their role concerning crime and security.

In 2005, through the publication of «police in the local community», the National Police Directorate (POD) promoted a division of work in which the public police would deal with the symptoms of crime, while the underlying causes would primarily be solved by other governmental agencies, particularly municipal agencies. This means that all municipalities in Norway are perceived to be important actors concerning the work with crime and security. As a consequence of this role, the municipality of Bergen has a stated objective that the city of Bergen should be a secure and safe city consisting of secure urban spaces for all its inhabitants (Bergen kommune, 2012). According to respondents affiliated to the municipality, this objective is sought to be achieved partly through a range of services that is directed towards children and adolescents with the aim of preventing crime within these groups (Respondent 12). One of the most important measures concerning the preventive actions directed to the youths is the program named Coordination of Local Drug and Crime Prevention (SLT). According to some of the respondents (1 and 12) the aim of the SLT is that when different actors meet on a regularly basis to exchange experiences and knowledge and to coordinate initiatives and responsibilities, it will result in a more effective crime prevention. However, SLT in Bergen is limited to public actors only. Another area where the local authority of Bergen has the opportunity to affect security is through its city planning and design of physical spaces. There is an assumption that thefts, violence and other vandalism occur where the physical spaces create blind spots in which there are few opportunities for insight and control (Aas et al., 2010). The consequences of this are seen through the Planning and Building Act of 2009 in which the municipality is required to take into account crime prevention when they handle planning and building applications. Thus, the municipality of Bergen may through thoughtful planning of the urban physical spaces affect how its citizens perceive security. The open drug scenes in Bergen are one particularly area where the municipality has started to work with the improvement of the physical space in order to reduce crime (mostly drug-related crime) and enhance security. Part of Nygårdsparken, for instance, was in 2014 closed to be upgraded and a range of actions is now being implemented (e.g. new lighting, increased visibility) which will make the park a safer place. In both these cases – SLT and city planning/design – inter-agency cooperation is an important feature which will be explored further below. Furthermore, it can be argued that the preventive strategies of the municipality build on two different mentalities – SLT is based on person-oriented prevention, while the urban planning is oriented towards situational crime prevention (Clarke & Mayhew, 1980; Lie, 2011).

In Norway, police services and activities are regulated by the Police Act (Lov om politiet). The main goal and responsibility is derived from the Police Act 1; «The police shall through preventive, enforcing and helping activities contribute to society’s overall effort to promote and consolidate the citizens’ security under the law, safety and welfare in general». This implies that the Norwegian police, in general, play an important role in the society, and that the police have an overall responsibility for providing security to the citizens. The main objective of the Norwegian police is further specified in the White Paper no. 42 Police role and tasks (2004 – 2005). Here, it is stated that the police objective is to contribute to increased safety and security within the local community. According to Aas et al. (2010), the police is the one institution in Norway which is most explicitly held responsible for general security in the society. Accordingly, the Norwegian police are both by law and politics ascribed a role with a particular responsibility – a guarantor – for the maintenance of public security. This is a role that has important consequences for the practices of local police services in Bergen.

When examining the case of the local police in Bergen, one can see that the described objective reflects the core tasks which the police are expected to maintain. One of the respondents, for example, states that their main task is «to maintain law and order, to create a sense of security, to prosecute criminal offences, but also to prevent crime.» (Respondent 2). In the Police Act, it is further stressed that the guiding principle for police work should be crime prevention. Thus, it is thought that public security in Norway is best maintained through the prevention of crime. The leading strategies for preventive actions have in the last decade been «problem-oriented policing» and «knowledge-based policing» (Politidirektoratet, 2002, 2008), where the latter is now the most prominent. Knowledge-based policing within the Norwegian context can be described as the systematic and methodical gathering of relevant information and knowledge, which is then analyzed in order to make strategic decisions about preventive measures with the aim to increase security (Finstad, 2000). According to Gundhus (2009), the gathered information is also perceived to be of a more scientific character compared to the traditional experience-based knowledge. Furthermore, in this strategy, it is a clear expectation that the police to a greater extent should search for knowledge and information outside the internal organization of the police (Justis- og politidepartementet, 2009). For the local police in Bergen, knowledge-based policing has resulted in an increased use of different analytical and mapping tools in order to prevent crime and enhance security, as Respondent 1 articulates

Clearly, the use of analysis, for instance, to really analyze what happens, when it happens and the like, in order to identify crimes and to implement measures against it has now become prominent. And these analytical tools were not previously available.

Analysis of information and knowledge about what types of crime are occurring, where it happens, how it happens, and which actors are involved have become important for the local police in Bergen regarding crime prevention. This suggests that the local police in Bergen want to work proactively with crime, which is also expressed by several of the respondents. This is also in line with one of the main objectives stated by POD during the last decade, that is, to get the local police to work more proactively and less reactively in terms of crime and security. Despite such an ideal, several of the respondents from the police in Bergen report that they still work more reactively than proactively, «We have to acknowledge that we probably are more reactive than proactive in much of the work we do» (Respondent 2). And, «In general, my officers are more on the reactive side; something happens and we get called to the site, and gather the threads from there» (Respondent 3). Accordingly, the scientific-based knowledge derived from PODs ideal seems to be overshadowed by the experience knowledge:

I am the one who is out in the field and it is I who experience it. And should I then hear later on … or should the statistics tell me this and that, for example that it is not that bad. Offences of violence in Bergen has decreased for example, oh well, the statistics says that. Yet, I’m the one who is out there and fight every Saturday night and feel it on my body. Although it [violence] has decreased it is still there. (Respondent 3).

This is similar to what Gundhus (2006, 2009) found in her study: the police staff still ranked knowledge and information based on experience more highly than the scientific. And more importantly, Gundhus suggest that this can be explained by the police culture, that is, real police work is perceived to be bandit-catching and not analyzing information.

Consequently, there seems to be a discrepancy between the expressed ideal of POD and the practices of the local police in terms of crime prevention. Some of the respondents from the police express that a part of the explanation may be ascribed to a lack of time and resources (Respondents 2 and 3). But another, and probably a more important reason, is that the police in Norway are bound by performance measurements which are derived from POD (Respondents 3 and 4). These measurements are used to assess how effectively the police conduct their work, and it influences the allocation of resources to the local police. The police have to report on a variety of reactive measures, however, according to the respondents there are no measurements of the preventive work conducted by the police. As a consequence, the preventive actions are often given a lower priority compared to the reactive work of the police. This strong focus on the reactive actions may be perceived as a paradox: the stated objective of POD is that the police should emphasize preventive actions, yet it is the reactive work on which the police are evaluated, which is also derived from POD. This is in line with what Larsson (2010) observes, that is, the crime prevention perspective of the police has been more concerned with rhetoric and ideology at a management and political level than with the practices of the police.

The findings so far indicate that the municipality undertakes a preventive role concerning crime and security in Bergen. The local police in Bergen express that they want to work proactively with crime and security, however, they are constrained by a variety of factors and consequently the reactive work seems to be given a higher priority. Nevertheless, the municipality and the local police perceive themselves as actors with a particular responsibility for the maintenance of security and crime in Bergen. These actors are therefore perceived as guarantors of the public good of security.

The private security industry – specialized in proactive policing

The introduction suggests that private actors are no longer a peripheral group within the security governance; they are now viewed as a key provider of security. The private actors examined in this article belong to the private security industry (Shearing & Stenning, 1981; Stenning & Shearing, 1980). But more importantly, although the public actors undertake a preventive role in terms of security governance, such an approach is not the monopoly of public actors. Actors belonging to the private security industry also pursue preventive actions in order to enhance security and to reduce crime. Therefore, it is of interest to compare how the public actors and the actors of the private security industry perceive their roles of prevention before analyzing how the private actors work.

In the case of security governance in Bergen both the public and private actors state that they attempt to work preventively in order to reduce crime and thus increase security. However, one can identify a clear distinction between how the two groups perceive the role of prevention. On the one hand, private security companies place their emphasis on the interests of their clients, that is, on private interest. The public actors, on the other hand, are more focused on the interests of society as a whole. Hence, the public actors are seeking to maintain a public interest or value. This distinction between private and public interests has been used by Shearing and Stenning (1981, p. 209) in order to distinguish between public and private security actors; «private security organizations exist essentially to serve the interests of those who employ them, rather than some more or less clearly defined ‘public interest’ which purportedly lies at the heart of the public (police) mandate.». Derived from this distinction, one can more clearly identify the different views on how the actors in Bergen perceived the role of prevention. Therefore, when public actors spoke about preventive measures they mainly referred to it as crime prevention. The private actors, however, described their role to a greater extent as loss prevention of client assets. Consequently, the private security companies in Bergen organized their business around clients’ or customers’ interests. Thus, these actors can be said to have a much narrower focus on crime and security than the public actors, as one respondent from the private security industry argues:

What differs in the mindset of private and public actors is often that the private actors are more focused on their own values, while the police (public) focus on society as a whole. So, if store A secures their business with a closed payment system which makes the store less interesting for a robber to commit a robbery, then the store reduces the amount of crime as well as they limit their losses. But the robber or burglar will still be able to go to the neighboring store and commit a burglary there if they have not secured their store sufficiently. This often means that the private sector’s focus is much narrower that the public police (actors) in regard to crime prevention. (Respondent 5).

This supports the findings above, that the public actors in Bergen perceive themselves as actors with a particular responsibility for the maintenance of public security. Accordingly, the aims of the preventive strategies of the public and private actors are different – the former around a general public interest and the latter around the client’s interest.

All the representatives from the private security companies stated that their main focus was on the client and on the client’s interests or values (Respondents 5, 4 10 and 13). Hence, how the private actors preformed their services was in large part governed by the clients’ premises. One of the respondents stated that their company had spent a substantial amount of time discussing whether proactive or reactive strategies were the best means to maintain security, and they concluded that the best way to ensure security was to work proactively (Respondent 5). According to the same respondent, however, whether to use proactive or reactive strategies depended entirely upon what the client wanted and how the client wanted to work with security:

People normally do not buy a bandage before they are hurt, they buy it afterwards. And it is a bit like this with the clients too; when a client has had a break-in or been the victim of a crime, they normally place security really high on the agenda and want to work proactively with crime and security. But, when we as a security provider come and tell you that you should implement certain routines in order for your business to be secured against these challenges, unless there is a security person who sits on the other side of the table and receives this message, it is not obvious that they want to put security and prevention high on the agenda.

Regarding proactive strategies to reduce crime and enhance security, analytical and statistical measures are of great importance for the private companies. All interviewed representatives affiliated with the private security industry in Bergen stated that they actively made use of such methods in order to prevent criminal offences against their clients. One respondent, for instance, stated that their company filed a report for every event where physical force had been used by their employees (Respondent 6). These statistics could then be used to keep track of places at the client that might have challenges or problems. Furthermore, measures could be implemented by the security company in places where it was needed. Again, the aim is directed towards the client interest. The statistics were not only used to keep track of places that might have challenges. Statistics could be used in cases where the public police wanted information about specific events. Respondent 6 illustrates this:

I am getting the specific report, and then I can read what has happened in the specific event. Well, in a way I know all that has happened. So when a representative of the police (anonymized) calls me on Monday morning and asks what happened during the weekend in the specific event, then I can tell him exactly what has happened.

Another respondent argues that they use statistical measures to determine whether they had worked well enough in order to prevent crime for their clients:

If a client uses NOK 3 million on security a year, we must dare to challenge both the client and ourselves when the year has passed and the money has been spent. Have we spent the money properly, or could we have worked differently with security, which would have led to lesser crime and better security for the client? (Respondent 5).

It is precisely in this regard that the use of statistical measures is perceived to be a good method. By keeping a record of all criminal events, Respondent 5 states that they were able to pinpoint which part of the client’s store is most affected by crime, what type of products are stolen most often, and which actors are involved in the crime. For instance, if there is a specific product that is overrepresented in the crime statistics then, according to Respondent 5, one can move the product to a more visible place in the store, and thus prevent its loss. In addition, statistical measures are used to create «hot spot» analysis to help identify high-crime areas. According to Respondents 5 and 10, the use of hot spot analysis is normally related to client visits. The hot spot analyses register areas with most call-outs from clients, that is, those areas with the most detected cases, and thus create a geographical map of areas that stand out as problem areas. The results from the analyses can then help the security companies to address the best means to respond to the situation (Respondents 5, 6 and 10). From the elaboration here, one can identify some parallels between the uses of statistical measures by the private actors and the police.

As highlighted above, the risk mentality is concerned with prevention of crimes and a central aspect of this future-oriented logic is instrumental calculations and techniques to reduce crime, danger and risk. The uses of statistical measures by the private security companies can be perceived as such instrumental calculations or techniques. Thus, the private security companies in Bergen can be said to have developed a specialized expertise within this proactive or risk-based mentality. And it seems that private security companies have just as good capacity for proactive work as the public police. This point is also highlighted by Shearing and Stenning (1981, 1983) as they argue that private security has some important advantages over the public police in terms of preventive policing. Hence, the private actors have a particular capacity within the proactive work in terms of crime and security. However, it is important to note that the aim of this specialization is tightly connected with the narrow focus of the client, that is, the intention of the private actors’ preventive actions is in large part directed by a private interest. One important question that arises, then, is what type of knowledge and expertise do the private actors possess that could be important for other actors, in particular the public police?

In order to explore this question one can look at the perceived security context in Bergen, that is, what types of crimes threaten citizens’ safety? During recent years one concern in terms of crime has been related to narcotics offences. In one particular (serious) case, some girls were drugged with Rohypnol and then raped. The police had information indicating that the offenders could be 4 or 5 Italians, however, they did not know their names or where to find them (Respondent 6). Then, the police approached the security company responsible for the security guards at most of the bars and restaurants in Bergen and asked for help. Respondent 6 states that «I got an email from the police, where they asked; can your guards please look for the people in the picture, and I printed up 100 copies; all the guards got one. Forty-five minutes later they were arrested at one of the bars». This suggests that the private actors can contribute to the work of police in criminal offences by increasing the «eyes» on the streets, though this example is situated more within a reactive track. However, the point of more «eyes» on the street in order to prevent crime is highlighted by another respondent:

You have 10,000 to 15,000 security guards [in Norway] who are out in the field every day, and the only thing that’s in their mind is to think of security. And then it is clear that they will notify if they observe something. So when the potential capacity that lies within this is not properly used or exploited, to multiply the number of eyes out there, I don’t understand. (Respondent 5).

And according to the respondent, this something refers in large part to situations or cases where the security guards identify opportunities for criminal offences to occur, which then can be prevented by the right measures. But more importantly, these cases are not only related to the clients’ interest, but to such opportunities more generally, that is, crimes that may threaten the public interest. Another example which can illustrate what knowledge and expertise could be of value for the public police is the use of hot-spot analysis by the private actors. As it is described above the use of such analyses is widespread to prevent crime. Due to the closing of Nygårdsparken, changes within the open drug scenes in Bergen have been observed (Respondents 1 and 10). Consequently, narcotic offences have moved to other part of Bergen; further, offences for profit have increased within these areas (Respondents 5 and 10). According to Respondent 10, the hot-spot analysis by the private actors has then been used to identify new problem areas in Bergen and the respondent thinks these analyses produce information that may be important not only for the protection of clients’ goods, but also for prevention in general;

You see, we are getting very good information from these hot-spot analyses, and I know this has helped our customers to reduce their losses, they have told me that, so you can say that this has prevented crime from occurring. And, since the closing of Nygårdsparken has started now, we have already observed more offences for profit from our analyses. (…). Such information I think is important for others, especially the police. (Respondent 10).

These examples indicate that the private actors involved in security governance in Bergen possess a capacity that can be utilized by other actors in order to prevent crime, not only prevent clients’ loss.

The emphasis in the empirical exploration has thus far been on the business of significant entities involved in security governance in Bergen, that is, how these actors work and think about security and crime. The analysis suggests that the private actors possess important knowledge and experience in terms of crime prevention. These resources may be important for the public actors, especially the police. As viewed above, knowledge-based policing is the expressed ideal of POD regarding crime and security, and within this there also lies an expectation that the police seek knowledge and information outside the internal organization of the police. In addition, inter-agency partnership was highlighted as an important feature of the preventive work of the municipality of Bergen. Thus, cooperation and partnerships seem to be crucial for the governance of security in Bergen. In the next section, my focus shifts towards collaboration and establishment of partnerships between public and private actors.

Network and partnerships – the security network of Bergen

A security network is defined as a set of institutional or individual nodes (actors) that are directly or indirectly connected in order to authorize and/or provide security for internal or external actors (Dupont, 2004; Shearing & Wood, 2000). Dupont (2004) presents four ideal types of security network, and one can classify the identified network in Bergen as a «local security network». This local security network comprises 32 actors who work directly or indirectly with local security and criminal challenges in the municipality of Bergen. These 32 actors belong to seven different sectors: public police, public (other public activities), private security, in-house security, voluntary, hybrid, and professional associations. Most often, local networks function as information exchanges concerning local crime and security issues, and emphasis is placed on the resources that can be mobilized to solve them (Dupont, 2004). Hence, local knowledge is of great importance. One important strategy for increasing the amount and quality of available resources for nodes is to enter into partnerships. It is the development and maintenance of these partnerships that represent the «bones» of the network. Thus, partnerships are conceived as (1) physical interactions between actors on issues concerning security; (2) the transfer of material and non-material resources for security purposes, such as information exchange and the pooling of CCTV and communication equipment; and (3) formal security roles dictated through the power and authority.

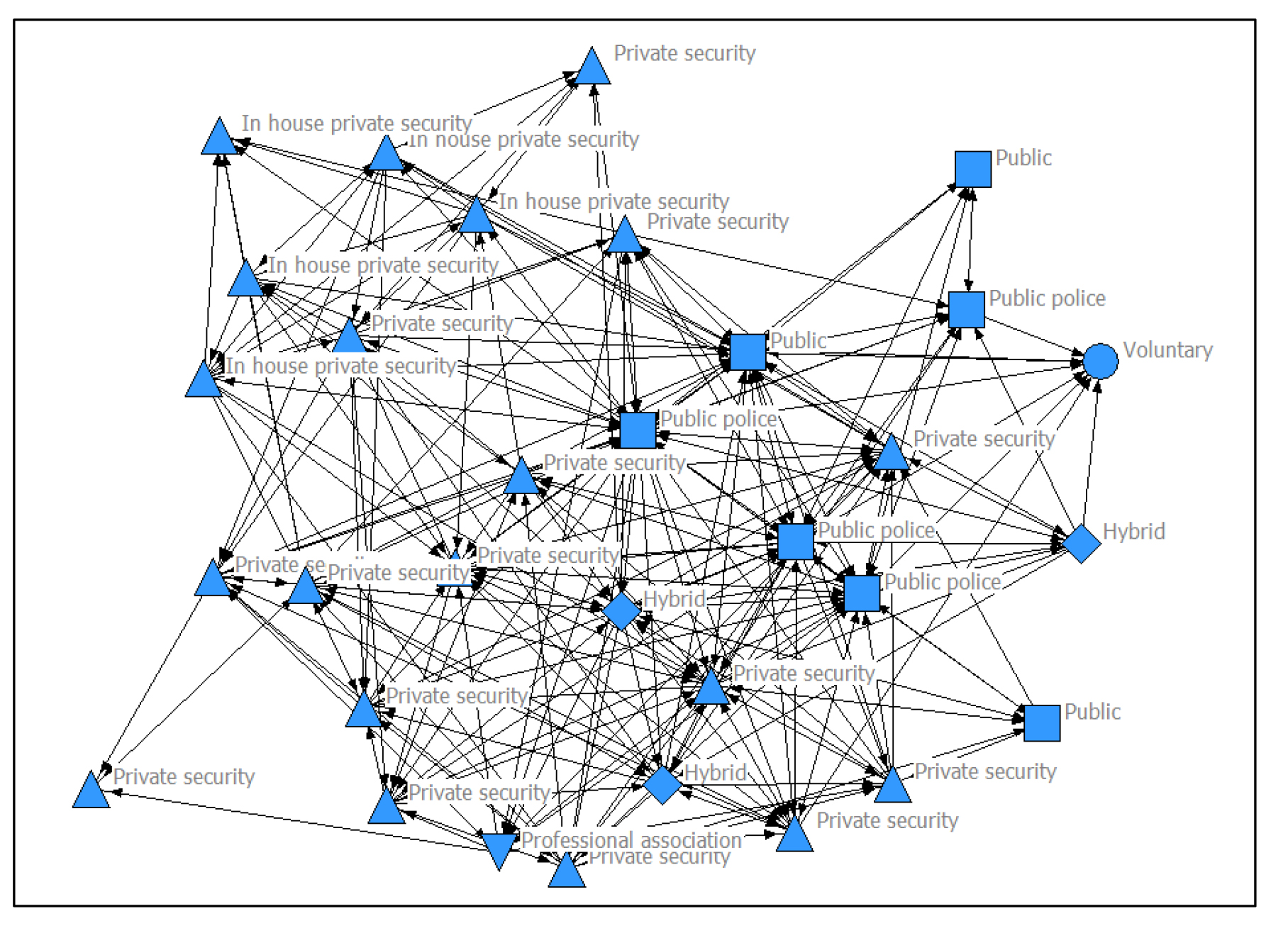

Figure 1 represents the patterns of partnerships of the local security network in Bergen. The actors reported a total of 304 active partnerships, and each line in the figure represents a partnership that was active over the previous twelve months. When exploring the visualization of the network (Figure 1), one can see that it is a dense network and that three of the actors within the public police sector possess a central position in the network – these actors have many outgoing and incoming partnerships.

Figure 1: The local security network in Bergen (spring embedding).

One challenge in examining the visualization of a network is that the larger and more complex the network is, the harder it is to conduct a good analysis (Grønmo, 2004). Due to the large number of actors and partnerships the network in Bergen is considered to be complex. One strategy to overcome this challenge is to make use of statistical measures derived from social network analysis. These measures can be used regardless of the size and complexity of the network (Breiger, 2004; López & Scott, 2000; Wasserman & Faust, 1994). In network analysis one can place emphasis at different levels of analysis; the network as a whole (macro-level) or at the individual actors (micro-level). Measure of density, average geodesic distance and centralization belong to the macro level, while the concept of centrality is a property of a node’s position in a network.

The security network in Bergen has an average density of 30.6 %, which means that 30.6% of all possible partnerships between the actors are considered to be active. To determine what could be considered as high or low density one needs to look at what type of actors are included and the number of actors. The density of the security network in Bergen is considered to be quite high due to the number of actors (32) and their heterogeneity, both in terms of their tasks and size. The density described here is the average density of the network as a whole, however, it is also possible to explore how the density is distributed between and within the different sectors (Borgatti, Everett, & Johnson, 2013). Above, inter-agency partnership was highlighted as an important feature of the preventive work of the municipality of Bergen. Inter-agency partnerships are defined as collaborative ties between public actors (density between the public police and the public sector). The analysis shows that the density between these sectors is 83%, suggesting that 83% of all possible partnerships between the actors within these two sectors are active. This density is perceived to be very high, indicating that there exists close links between the public actors. When examining the density of the network it is also of interest to analyze the connectivity and distance between nodes, more precisely through the average geodesic distance. The analysis shows that the average geodesic distance in the network is 1.8, which is considered a low figure. This implies that nodes may come in contact with all the other nodes of the network through just under two intermediaries. In such a dense network, where actors have many alternatives to reach the same nodes, the potential for information and resource exchange is high, and the information travels fast through the boundaries of the network. This may help explaining why actors want to belong to a network.

Another important dimension of the network analysis is centrality. The centrality measure is tightly coupled with the concept of power and how power is distributed within the boundaries of the network (Borgatti, 2005; Borgatti et al., 2013; Freeman, 1979). According to Dupont (2006a, p. 175) the more central a node’s position in the network is, the more opportunities it will have, the fewer constraints it will experience, and the more influence it will derive from its position in the network. Nodes with a central position will therefore have a greater potential of influencing the course of events. A range of centrality concepts have been put forth in the literature of network analysis. However, in this study two different centrality concepts is used; degree centrality and betweenness centrality.

The network data used in this article is directed, thus an outdegree and indegree of degree centrality is defined. The analysis of degree centrality in the network shows that the two actors with the highest outdegree come from the public police sector; one of them has 26 out of 31 possible active outgoing partnerships. The same actor has an indegree centrality of 29. Out of the top five actors with the highest outdegree, three of them are found in the public police sector. Examining the same figures of indegree one find that two of the top five are from the public police sector. Thus, the most central authorities within the network are the public police sector. To further investigate this assumption one can look at the percentage of ties maintained to the public police sector. In the network, 52% of all the actors state that they maintain a partnership with actors belonging to the public police sector. By way of comparison, the average percentage for the non-police actors in the network was 27%.

The analysis of degree centrality is valuable in that it pinpoint the most connected actors, but it does not capture the fact that some actors may be key intermediaries linking other nodes (Brewer, 2014, p. see also; Granovetter, 1973). In order to measure strategically placed actors within the network, betweenness centrality is more useful. The analysis of betweenness centrality shows that the most strategically placed actor is one from the public police sector, with a score of 30.39. The score is remarkably higher than the next one, which is a private security company with a score of 9.34. This statistic indicates that the public police actor possesses an important brokerage function within the boundaries of the network, and it is critical to the overall effectiveness of the network.

Centralization is a measurement at the macro-level, but it is tightly coupled with the centrality concept. A network with a high centralization index implies that the network is dominated by one or a few nodes (Wasserman & Faust, 1994). Hence, these nodes have a greater potential of controlling the flow of information or resources compared to others. Centralization is of interest because the analysis of centrality above indicated that the public police sector possesses a central position in the network. Since the data is directed, the centralization index is also divided into an out- and an in-centralization index. The analysis shows that the security network has an out-index of 56.8% and an in-index of 67%. These figures are perceived to be high, suggesting that the network in Bergen is dominated by one or a few nodes. Due to the fact that centralization and centrality measures are related – and that the public police have the highest centrality scores – it is interesting to explore the centralization index when the public police sector is removed from the analysis. Now, the analysis shows an out-centralization index in the network of 26% and an in-centralization of 29.8%. This is a substantial reduction, confirming that the network in Bergen is dominated by one particular group of actors – the public police sector.

The analysis of the local security network – both at macro- and micro-level – indicates that the public police possess a central position in the network in Bergen. The police maintain a substantial amount of outgoing partnerships as well as having many incoming partnerships. This suggests, to borrow Dupont’s (2006a) words, that the public police are both «in search» and «in demand» of partnerships. A central question, then, is what can explain the central position of the public police in the network? In terms of outgoing partnerships, one can identify two possible explanations. First, in the questionnaire, respondents had the opportunity to come with their own reflections on three questions. It is relevant to highlight the views of the respondents in terms of what role the police should have in collaborative networks. The general perception by the respondents was that the police should have an initiating role in terms of partnerships. Second, POD stresses that the local police in Norway should seek to form partnerships with other actors regarding crime prevention. In sum, these aspects indicate that the public police should have many outgoing partnerships – they are in search. With respect of the amount of incoming partnerships the public police are controlling two essential resources; first, the police possess a monopoly on the legitimate use of force; this is expressed in the Police Act 6. And second, the police control the access to crime-related information through a variety of records, such as the criminal-intelligence register, electronic-criminal records, and the personal-identity register. If other actors want/need to use force (excluding the principles of necessity and self-defense) or need crime-related information they must come into contact with the public police, and thus create a partnership with the police – hence the police is in demand.

Furthermore, the network analysis shows that partnerships seem to be an integral part of the preventive work in Bergen. This resembles what Gundhus, Egge, Strype, and Myrher (2008) found in their evaluation of SLT, that is, collaboration via SLT was important for the overall work with crime prevention in Norway. The evaluation showed that there exist close collaborative ties between the police, municipality and other public actors – suggesting that public participation is a key aspect in preventive actions. This is also in line with the findings presented above. However, the analysis of Gundhus et al. (2008) highlights another element regarding the cooperation, that is, private participation within SLT seems to be lacking. Aspects of public-private cooperation in Bergen will be further explored below.

Through the exploration and discussion of the security network it is illustrated that the public police sector possesses a central position and function in the network, and thus has a greater potential to influence security governance than other actors. While the statistical network analysis is valuable in identifying the potential of influence, it does not necessarily capture whether the potential is successfully exploited by the actor(s). Consequently, one needs to explore whether the potential that the public police possess is fully utilized in Bergen.

Cooperative relations in the governance of Security in Bergen

A good point of departure is to look back at the network analysis. An analysis of the degree of formalization of the partnerships was conducted. Of the 304 active partnerships 48% of these were perceived to be of an informal character, while the proportion of formal partnerships was 32% (20% were of both a formal and informal character). These figures suggest that a large part of the partnerships in the network are informal. Since the private security companies seem to possess knowledge and expertise that may be of value for the public police, it is of interest to assess the degree of formalization for these actors. The analysis shows that 88% of the partnerships between the police and the private security companies were of an informal character – suggesting that there exists little formalized collaboration between these actors in Bergen. This point is also supported through interviews with representatives from both the police and the private actors. Regarding crime and security in Bergen, a formalized police board (politirådet) has been established. Here, top management from the police and the municipality meet on a regular basis to discuss and coordinate their work on crime and security. The board was established back in 2010. But since the inception, membership and participation has been limited to actors belonging to the public sector, even though it is stated in public documents and from representatives of the board that the police board is open for other actors as well (both private and voluntary) (Respondent 1). When representatives from the police and the municipality were asked about the opportunity for private security companies to participate, one representatives stated that this had never been a topic for the police board, and the same respondent further stated that he had never thought of this possibility at all (Respondent 7). And according to Respondent 1, the board is not the right arena for the participation of private companies. The police board in Bergen is thus limited to actors belonging to the public sector, as an area of inter-agency partnerships. This differs from policing boards or forums found in other countries. In Canada, for instance, private participation is embraced (Law Commission of Canada, 2006).

Through interviews with several of the representatives from the private security companies, it is stated that they want to participate in formal and strategic discussions and collaborations with the police and the municipality in relation to crime and security in Bergen, and the police board was highlighted as one possible arena (Respondents 5, 10 and 13). This can be illustrated by Respondent 5 who argues:

I think the concept [police board] is really good. (…) But there are more actors than just the public who work with and govern security. Hence, it should be possible for those actors as well to participate in the board, so that one can work together with the security.

And Respondent 5 further questions the present solution with the police board:

I at least question whether or not we have maintained security well enough with the current solution with the police board, or if there are changes that can be made in order to work better with them and maintain security in a better way.

From this one can draw the conclusion that there exists a weak or little formalized collaboration between the public actors (police and municipality) and the private security companies. As a consequence, both the public and private actors may miss out on important local knowledge that can have implications for how security is best maintained in Bergen.

On the other hand, as shown above, there exists a substantial amount of informal collaboration between the two sectors. These informal relationships are described as good by representatives from the public sector and the private industry. However, they are only concerned with exchange of case-specific information at an operational level, and not exchange of strategic information and discussion of the security situation at an overall level. Though the informal relationships are considered good, representatives from the private security argue that there is little reciprocity regarding the exchange between the private actors and the police, as well as the municipality (Respondents 5, 6 and 10). This indicates an asymmetry in the relationship between private and public actors – the direction of the exchange goes mainly from private actors to police, and not vice versa. This asymmetry, according to the respondents, causes constraints regarding their work with crime and security; «The more information we have, it would lead to a wider, what shall I say, information center. So, the more we know about what we should pay attention to and focus on, would be very helpful for us.» (Respondent 10). Consequently, the private security companies want a greater reciprocity in the informal information exchange (Respondents 5, 6, 10 and 13). The asymmetry described here illustrates an important point; the collaboration between the police and the private actors does not take place within a framework of equality. Thus, the public police do not view the private security companies as equal partners. And at the same time, all of the respondents from the private security state that they want to move the informal collaboration with the police to a higher, more formalized level.

Turning to the inter-agency partnerships, the police and the municipality are cooperating and sharing information and knowledge on many occasions. One important arena for these inter-agency partnerships is the already mentioned police board. However, inter-agency partnerships also take place in other arenas. For instance, the police and the municipality have established a coordination group which is expected to work with the challenges concerning the open drug scenes in Bergen, and in particular with the closing of Nygårdsparken. SLT is a second arena where inter-agency collaboration exists. These different partnerships are also consistent with the knowledge-based policing that guides the work of the public police in Bergen. Thus, the police do in fact search for knowledge outside the internal organization of the police, but this search is in large part limited to other public agencies. Which means that actors involved in the security governance in Bergen may miss out on important knowledge and expertise.

The relationship between private actors and the police in Bergen seems to consist of a paradoxical element. On the one hand, several of the representatives from the police (Respondents 1, 3 and 4) express that they are dependent on a range of actors – including the private security companies – in order to work effectively with crime and security. There is also a broad political consensus about the fact that the police are unable to solve all security problems alone, hence the police are expected to collaborate with other relevant actors:

The police shall in cooperation with other public and private actors contribute to enhanced safety in society. Citizens’ safety will be increased through reduced crime, increased availability and information. The police with their many important and demanding tasks need to clarify the roles with their cooperating actors. (Justis- og politidepartementet, 2005, p. 6). It is necessary to recognize that the police have neither the resources nor the expertise to work on all levels, and should therefore cooperate with other agencies to solve the assigned tasks. (Politidirektoratet, 2005, p. 11).

On the other hand, as the discussion illustrates, there exists little formalized collaboration between the private security companies and the public police, even though the police express that the private sector is important in the work of security. At the same time, it appears that the police do not acknowledge the role the private security companies possess. One respondent affiliated to the private sector captured this point nicely:

Once there was a traffic accident down at «Bryggen», we were down there doing another job and we were asked by the police if we could help to stop the traffic. A very simple task, anyone could do it. Some of our employees took on the task of stopping the traffic there. The immediate reaction to it was, first of all, some cars tried to get past, create some traffic congestion. Secondly, the accident was featured in the newspaper, and here it was claimed that some security guards were stopping the traffic down at «Bryggen», but without the fact that the police had asked us to do it. I’ve got it on record that the police asked us to help them, but the police did not express this at all when it became an issue in the media. And yes, this had negative consequences for us, «Security guards stood there stopping the traffic and thought they were the police»; Hello, that’s not what happened! (Respondent 6).

This example captures the paradoxical element of the relationship between the police and the private security companies in Bergen. The police are dependent on private actors – which they also express themselves – in order to work effectively with security. However, the public police do not necessarily want to express this, nor to formalize the cooperation with the private sector to a greater extent, e.g. by including them in the police board. Looking at the private security companies, the respondents state that they want to contribute to a greater extent – especially in terms of formalizing the collaboration and increasing the opportunities for strategic discussions of the overall security situation in Bergen. The respondents from the private security industry also express that they possess a great amount of knowledge and expertise that could be used to work better with security governance in Bergen. The private sector can therefore be perceived as an important resource that can be utilized, but the public police do not show any particular interest in adopting and acknowledging these resources or formalizing the collaboration. The discussion above also illustrates that the little (informal) collaboration which in fact does exist between the public police and private actors does not contain the important element of equality. The public police only mobilize the private security companies as a channel of information for their own benefit. In sum, it seems that the public police do not fully exploit the potential they have gained through the central position in the security network, indicating that there is an unfulfilled potential in the security governance in Bergen.

Conclusion – The unfulfilled potential of security governance in the city of Bergen

The question which has been addressed in this article and has guided the empirical analysis is; what characterizes security governance in a Norwegian context? In order to explore this I have undertaken a descriptive account and I have analyzed the local security governance in the city of Bergen. To summarize the findings from the empirical analysis; first, the security governance in Bergen consists of several actors, which is consistent with the pluralization. Each of the actors analyzed does possess important resources and expertise which can be mobilized in order to work effectively with crime and security. The two actors examined first, the municipality of Bergen and the local police, perceive themselves as guarantors of the public security, and both have a stated objective to work proactively with security and crime. The analysis, however, indicates that the public police are still situated in a reactive track concerning their work with crime. This seems in large part to be connected with the performance measurements that the police have to report on, which do not focus on preventive measures. Therefore, the crime prevention perspective is more concerned with rhetoric than with the practices of everyday police work. The private security companies are also viewed as central actors in the security governance in Bergen. The analysis showed that these actors have specialized themselves within the preventive mentality and it is suggested that they may be as good or even better that the public police at preventive and future focused measures regarding crime and security. In terms of prevention, however, an important difference has been identified in how these actors (public and private) perceive the role of prevention. The public actors are more concerned with a public interest, while the private actors have located themselves in the prevention of a private interest. One important question in this regard has been concerned with what sort of knowledge and expertise the private actors possess, which could be important for other actors. Here, the analysis suggests that the private actors could increase the «eyes» on the street, but also the use of statistical measures may contribute with important knowledge. Second, the security governance in Bergen is characterized by partnerships and collaboration. This has been explored through the network analysis, and it is suggested that the public police sector possess a very central position within the boundaries of the network. Such a position gives the public police a greater potential than others to influence security governance in Bergen. This potential has also been explored, and the analysis indicates that there is an unfulfilled potential in terms of collaboration in the security network, especially between the public police and the private actors. One important question that arises from this finding is how can one explain the unfulfilled potential in the security governance in Bergen? I will end this article by exploring this question further, and in order to seek an explanation, I will return to the theoretical framework of nodal governance and state anchored pluralism introduced earlier. When the unfulfilled potential is not fully utilized by the actors, is it caused by a lack of conditions for the nodal governance approach or the approach of state-anchored pluralism, or both?

Two of the most important conditions derived from state-anchored pluralism are, first, that the public police must possess a central position within security governance, and second, the public police must be oriented towards the maintenance of a public interest or value. The empirical findings presented in this article have shown that the public police (as well as the municipality) in Bergen view themselves as the main guarantor of public security and that they have oriented their work towards the maintenance of the public interests. Through the empirical analysis, it is also shown that the police possess a central position in the production and delivery of security. Consequently, it can be argued that the security governance is anchored within the public police in Bergen. Thus, the two conditions derived from the framework of state-anchored pluralism are fulfilled, and these conditions are, as such, perceived to be beneficial for the maintenance of security governance in Bergen.