Donald Trump’s Golf Resort in Aberdeenshire, Scotland: The ‘Greatest’ Incomplete Planning Disaster in the World?

William Walton

Senior Lecturer

Northumbria Law School

Publisert 25.01.2019, Oslo Law Review 2018/3, Årgang 5, side 175-196

In 2006, Donald Trump submitted a planning application to transform an area of protected dunes and open countryside along the coast of north-east Scotland into a major golf and leisure resort. He claimed the golf course would be the greatest in the world and would transform the region’s oil economy. Citing the economic benefits, the Scottish Government approved the project in 2008. Trump has constructed the golf course but has failed to deliver the hotel and other elements of the project. Against the backdrop of planning deregulation, the paper examines why the officials failed to include appropriate planning conditions to ensure delivery of the project and prevent a great incomplete planning disaster. Recognising the limitations of current public law enforcement mechanisms, it invokes concepts borrowed from contract law. Holding that Trump is in breach of contract and has benefitted from unjust enrichment, it broaches the possibility of applying damages, restitution and specific performance as alternative remedies.

Key words

- Trump

- golf resort

- planning disaster

- environmental protection

- contract law

- unjust enrichment

- remedies for incomplete project.

1. INTRODUCTION

The UK planning system has, from the time of its comprehensive introduction in the late 1940s, afforded a high level of protection to areas of high landscape value and ecological significance. Beyond cities and urban areas, large swathes of landscape, in particular uplands and coastal areas, have been protected through a network of designations including national parks, areas of outstanding natural beauty, and sites of special scientific interest. As a result, despite its large population, the UK has managed to retain large areas that, to all intents and purposes, are off limits to most forms of development including large-scale housing, mineral exploitation and energy infrastructure. Nevertheless, the statutory framework still provides local planning authorities and government ministers with considerable discretionary powers that allow them to depart from the policies of approved statutory development plans and permit proposals for development in protected areas where they consider the economic and other advantages significantly outweigh the disadvantages. Where development proposals are brought forward, the promoter will have to discharge the burden of demonstrating that the scheme cannot be accommodated elsewhere on non-protected land. Inevitably, the very qualities that make a landscape worthy of a high level of protection also make it attractive to developers, in particular those promoting leisure schemes where environmental amenity will often be of intrinsic importance to the overall customer experience.

Large leisure resorts were developed in some of the UK’s most pristine environments following the establishment of the railway network in the mid 19th century and the advent of organised tourism for the emerging middle classes. One form of leisure activity – golf – was actively promoted by the private rail companies, which developed their own resort destinations in upland and coastal locations in Scotland from the late 1890s onward at places such as Cruden Bay, Portpatrick, Gleneagles, Turnberry and North Berwick. From the 1960s onward, the growth of another form of leisure – skiing – resulted in relatively modest sized resorts being developed in mountainous parts of Scotland such as at Glencoe, Glenshee and the Cairngorms. More recently, family activity resorts (such as the concept associated with Center Parcs developments) have been established in forest locations such as at Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire and Longleat in Somerset in England.

The environmental impacts of many of these types of development in the UK and elsewhere in the world – such as along the South Carolina coast in the USA – have been well documented. Proposals for large-scale resort-type leisure developments in such fragile locations and environments present significant problems for the planning system within the context of a market economy. First, what level of projected economic and social benefits from the proposal should be required to offset damage to ecological and environmental capital? Second, what level of certainty should be attached to the delivery of projected economic and social benefits? Third, what mechanisms should be deployed to ensure that the projected economic and social benefits are delivered and secured by the community?

Given that such projects are exceptionally permissible within the system, clearly every effort should be made to maximise the social and economic benefits and minimise the environmental costs. Securing delivery of the projected benefits – which are impliedly derivative of completion of the project – is likely to be highly problematic given the vulnerability of highly discretionary leisure-based expenditure to the vicissitudes of the free market. This problem is likely to be compounded for projects incorporating several discrete elements to be built over several years or decades. However, councils can seek to minimise the risk of incomplete delivery through their planning powers to impose conditions and to enter into an agreement with the applicant. Since any failure by the developer to comply with such conditions or to discharge any agreements can lead to the possible revocation of the consent, these are potentially effective enforcement mechanisms.

This paper seeks to explain why the statutory planning system has demonstrably failed to secure the construction of all of the built components of a major leisure-resort complex that were guaranteed as ‘compensation’ for the approval of a golf course on a deserted coastal site at Menie in north-east Scotland in 2008. As elaborated below, the applicant, Donald Trump, considered the coastal site to have unique topographical qualities that would provide for a world-class golf course. Much has already been written about this episode. Of particular note, Jonsson and Baeten contend that the ‘…existing planning practices … [were] … brushed aside …’ by the forces of neoliberalism combined with the entrepreneurial instincts of Trump. This paper contends that whilst neoliberalism – broadly understood as the operation of free markets within an increasingly deregulated economy and unequal society – undoubtedly provides the context within which the proposal was promoted, there was nothing inevitable about the outcome. Instead, to understand why a project that was so contrary to the development plan was approved – but so far not completed – the paper argues that one has to look to the individual failings of the planning officers, councillors, Planning Reporters and the Minister to vet the application properly and subject it to appropriate conditions to ensure its completion.

The mistakes made by the decision makers have resulted in a development that bears the hallmarks of a ‘great planning disaster’. This episode was played out under a planning system that was significantly deregulated through the Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006. Through a series of reforms, the Scottish Government sought to inculcate a ‘cultural change’, encouraging planners and councils to approach proposals for development more positively and to be less rule-constrained. This new approach very much reflected the views of industry, which provided some of the ammunition used by the local and national press in what was an intense campaign to pressurise the planners and councillors to approve the Menie project and a number of other large schemes around Scotland.

In order to provide a lens through which to view the decision to approve the scheme at Menie and the subsequent failure by the developer to construct the built elements of the project, the paper commences by revisiting Sir Peter Hall’s landmark analysis of the root causes of great planning disasters. It then moves on to outline the principal mechanisms of the Scottish planning system relevant to this project, before examining the changes made by Scottish governments to the planning system post 2006 to reduce delay in the determination of major development projects and produce ‘sustainable economic growth’. Outlining the proposals put forward by Trump, the paper then conducts what Hall calls a ‘pathological investigation’ of the disaster by examining the role of the decision makers to elicit why the planning application was approved without an appropriate condition requiring completion of the hotel and time-share elements of the project prior to the opening of the golf course.

Finally, noting the general weakness of planning regulations to force completion of large-scale multi-component projects, the paper considers the scope for using concepts and remedies borrowed from contract law to analyse and redress the failures of the developer to provide the promised benefits of the Menie project – an approach that I call ‘planning as contract’. There is a considerable body of work on ‘planning by contract’, based largely on research carried out in Hong Kong, through which leases and restrictive/positive covenants are used to regulate such matters as plot ratios, set-backs and building heights as well as the use of buildings and land. In suggesting that planning permissions create quasi-contractual obligations between the applicant and the decision maker, this paper is hoping to prompt a discussion around the approach that councils and central government should take towards developers that walk away from incomplete large-scale projects.

2. GREAT PLANNING DISASTERS

In his iconic text, Sir Peter Hall identified two categories of great planning disaster: those which had been completed against the advice of informed people, only to be widely perceived to have gone wrong, which he referred to as positive disasters; and those which had not been completed, but which avoided widespread criticism through being reversed or modified at great expense, which he referred to as negative disasters. Hall contended that the root cause of all great planning disasters was uncertainty about the future – something which is intrinsic to spatial planning. He divided this uncertainty into three separate categories, which he recognised were essentially inter-dependent. First, there was uncertainty in the environment (which he labelled UE), which arose largely through changes in the size of the market and changes in cost structure. Second, there was uncertainty in related decision areas (UR), which arose through the development of rival projects. Finally, there was uncertainty in value systems (UV), which caused changes in preferences.

Hall examined one great negative planning disaster (the London orbital motorway system), three great positive planning disasters (Concorde, Sydney Opera House and the Bay Area Rapid Transit system in San Francisco) and two near great planning disasters (the British Library and the University of California’s campus plans). The disasters were characterised through a combination of factors including project inflexibility, the uncontrolled escalation of costs and a refusal to abort even though the costs of proceeding outweighed the benefits. Positive or negative great planning disasters can be averted by fortuitous, unanticipated exogenous events such as the unexpected availability of an uncontroversial site adjacent to St Pancras railway station for the British Library following the decision to abandon one at Bloomsbury. But since we cannot rely on good fortune, Hall suggests that planning officers and politicians should take a ‘wait and see’ incremental approach to major projects – such as expanding existing airports or widening existing roads until such time as that strategy becomes unviable.

As Hall notes, within a pluralist society we have to ask who benefits, who pays and who decides the fate of mega-projects. In particular, as evidenced by the recent furores over the new Scottish parliament and Edinburgh’s new tram project, it is the ‘who pays’ (or how much?) question for large public projects that appears to generate most public hostility. Whilst privately funded projects – such as Trump’s at Menie – will not negatively impact public finances, they will, when brought forward in sensitive locations, impose significant environmental costs. If we accept neoliberal principles that the environment can be traded for economic and social benefits, then we need to be able to calculate those exchanges accurately and, to a return to a point made earlier, ensure that the benefits are delivered.

3. THE SCOTTISH PLANNING SYSTEM AND ITS REFORM

Since 1991, Scotland has operated a plan-led planning system in which proposals that are consistent with the development plan are usually approved, and those that are inconsistent are usually refused. In order for a council to depart from the development plan and approve a proposal on an unallocated site, there must be ‘other material considerations’ sufficient to offset non-compliance with the plan. In carrying out this planning balance-sheet computation, councils can have regard to the potential economic benefits of a proposal, but usually only when the project satisfies a need that cannot be met elsewhere at lower environmental cost. Further, councils are obliged to take wider economic growth objectives contained within government circulars, national planning policy guidance (NPPGs) and Scottish Planning Policy (SPPs) into consideration.

Applications for large-scale projects are determined by elected councillors sitting in a planning committee and acting under advice from professional planning officers. In exceptional circumstances – such as where a council proposes to grant permission for a development materially in conflict with its own development plan or against the grain of national policy guidance – the Scottish Government has the power to recover an application by calling it in for its own determination. Similarly, where the local council decides to refuse the application, the developer has the right to appeal to the Minister with the evidence often being presented at a public inquiry before a Planning Reporter.

In approving any application, the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 (s 37) empowers the council to attach conditions that it considers to be appropriate and (s 75) to enter into agreements regulating the use of land. Since the majority of planning applications (around 90%) are approved, it is this power to impose conditions and enter into agreements that provides a planning authority with the greatest level of control over development. The courts have held that conditions and agreements must be relevant to land use, relevant to the approved project and reasonable. In addition, the Scottish Government has stated that conditions should also be enforceable, precise and necessary. All projects will be subject to the condition that the development must commence within three years and must conform to the approved plans. Importantly, large projects containing separate elements will be normally subject to a phasing condition to ensure that the entire development is delivered in an orderly fashion. A developer failing to comply with a condition can be subject to enforcement action by the council. It is important to note that where the condition is held to be fundamental to the planning permission (condition precedent), a breach can lead to that permission being rendered void.

Notwithstanding the inherent flexibility within the Scottish planning system identified above, by the late 1990s there was a belief in some quarters that it was too slow and cumbersome, hindering economic growth. To meet this challenge, a programme of planning reform was initiated in 1999 shortly after the creation of the new Scottish Parliament. Following a series of consultation papers, a White Paper – Modernising the Planning System – was issued in 2005. Drawing the findings from the consultation papers together, the White Paper contended that the planning system needed to be significantly deregulated in order to ensure that more development was brought forward to provide for sustainable economic growth. In order to make the planning system fit for purpose, those operating within the system needed to undergo a cultural change and look more positively upon proposals for new development. Greater levels of development were to be achieved through the speedier production of longer term, more visionary development plans and through more rapid determination of planning applications. These proposals were incorporated into the Planning etc. (Scotland) Bill introduced in late 2005.

These new diluted provisions affecting the preparation of new development plans, however, would not take effect for several years after the introduction of the Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006. Both of the development plans relevant to the determination of the Trump application were adopted before any proposal at Menie had been intimated. Moreover, the new legislation did not amend the primacy accorded to the development plan, meaning that the Trump application would be assessed against the plans that made no provision for the project. However, the priority that planning reform gave to the pursuit of national economic growth was critical in creating an atmosphere in which the application became very difficult – but not impossible – to refuse.

4. THE MENIE GOLF RESORT PROPOSAL

In March 2006, more or less at the height of the 2002–2007 stock market boom, the US billionaire developer, Donald Trump, announced that he had acquired a 452 hectare property at Menie and was going to build two golf courses (one of which, Trump claimed, would be ‘…the greatest links golf course in the world…’), a 450-bedroom hotel, 950 time-share units, staff accommodation buildings and 500 houses. It was immediately evident that all of the elements of the proposal would directly conflict with the development plan, which sought to prohibit virtually any development on the application site.

Significantly, part of the championship golf course was on the Foveran Links Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), designated due to its large mobile dune systems. SSSIs provide a high – but not an absolute – level of protection as reflected in national and local policy. Under paragraph 25 of NPPG14: Natural Heritage, planning permission can be granted for projects compromising the overall integrity of the SSSI designation if those impacts are clearly outweighed by social or economic benefits of national importance. This policy was transposed almost word for word into the upper-tier strategic development plan. Aberdeenshire Council’s lower-tier plan policy, however, was far more stringent than national guidance. Under policy Env\2, development on SSSIs would only be permitted where the adverse impacts were clearly outweighed by social and economic benefits of national importance, where the overall integrity of the SSSI was not compromised and where there were no alternative sites available.

Unperturbed by these constraints, Trump assumed the mantle of a celebrity whose charisma and track record of delivering high quality developments would be enough to win over any doubters to his dream scheme. However, this track record was open to question, with two-thirds of his ventures having resulted in serious problems or failure. Planners used to engaging in co-operative, collaborative-style negotiations with applicants were confronted with an overtly competitive developer who adopted a high-handed approach. To persuade the planners and the councillors to set aside the SSSI constraint, the applicant invoked hyperbole to exaggerate the benefits of the development. He promised it would be so awe-inspiring that it would act as a catalyst for the transformation of the oil-based Aberdeen economy into one heavily dependent upon golf-based tourism. In demanding that planners looked beyond their apparently irrelevant development plans to share his bold vision, he was, in many ways, in tune with the tone of the White Paper and its exhortation for a cultural change.

5. ASSESSMENT AND DETERMINATION OF THE MENIE PLANNING APPLICATION

5.1 The Planning Officer’s Assessment

The outline planning application for a golf-leisure complex at Menie was submitted by Trump International Golf Club Scotland Ltd to Aberdeenshire Council and registered in November 2006. The planning officer treated the application as two separate elements – the golf course, hotel, time-share units and workers’ accommodation (the ‘commercial element’) – and the private housing (the ‘residential element’). The applicant claimed that the residential element was required to reduce the financial risk of the commercial element. Although a viability study revealed that the project would still be profitable – albeit less so – without the residential element, the planning officer chose to play down this finding and accepted that additional development was required to offset the risk.

It was acknowledged that all of the built elements of the resort were contrary to the council’s development plan but that, in line with national policy, these policy conflicts could be set aside for economic benefits. According to the applicant’s economic consultants, around 6,250 construction jobs could be created in the short term with another 1,250 over the long term, although (tellingly) the planning officer acknowledged that there were ‘no certainties’ (cf. Hall’s UE). There was a failure by the planning staff to acknowledge that the housing construction jobs would probably be displaced from elsewhere within the area. There was no consideration of less favourable economic scenarios. There were clear signs throughout the report of the inherent tendency of government bodies to engage in optimum bias by overestimating benefits and underestimating costs of mega-projects.

Using language that indicated a predisposition towards approval, it stated that it was ‘unfortunate’ that part of the course was located within the Foveran Links SSSI where local policy only permitted development in exceptional circumstances and where the objectives of the designation and overall integrity of the area would not be compromised. However, the planning officer concluded that the proposal would only cause ‘a reasonable degree of disturbance’ and continued that the development would ‘generally add to the quality of the environment … with appropriate mitigation (and) management’. It is no doubt because the planning officer came to this conclusion that she found it unnecessary to scrutinise closely claims that there were no more suitable alternative sites. Instead, the planning officer felt it sufficient to equate the admittedly rather nebulous concept of ‘need’ with the applicant’s willingness to invest to meet an asserted demand.

Bringing all of these matters together, the planning officer’s report concluded that the project would not cause such damage to the SSSI as to justify refusal. It went on to state that the ‘social and economic benefits are of national importance … that … override the adverse environmental impacts’. Appealing to the need for vision set out in the White Paper and setting aside the current development plan, the report stated that the project was one ‘which no planner or Development Plan could have foreseen and such an opportunity to diversify the economic base must be grasped’. The impact on the SSSI and other environmental issues must be set aside ‘in this instance to allow this level of economic and tourism investment to take place’.

The view of many objectors was that the golf course was a Trojan horse for the hotel and housing. What appears to have been overlooked by the planning officer was the possibility that the hotel and housing were actually a Trojan horse for the golf course. The planning officer did recommend that the championship golf course, hotel and chalets had to be constructed first, with the construction of the residential element to be phased in line with the completion of specified stages of the time-share units. However, the planning officer did not include a condition prohibiting the golf course from being opened prior to the completion of the hotel, chalets and time-share units which were, financially, the riskiest elements of the project but economically the most important to the council. Such a condition could have been worded: ‘The Championship Golf Course shall not be opened for play until the approved hotel, time share units and golf chalets have been completed and opened’.

In this situation, both principal parties – the applicant and the local authority – were seeking to manage risk. The applicant might have contended that this condition would be unreasonable until the course had matured and established a reputation. But such a response would have suggested that his braggadocious claims that the golf course would be the greatest in the world were, to use an American expression, ‘all hat and no cattle’. Moreover, the Council’s agreement to include 500 open market houses contrary to policy was a concession to offset the commercial risk attendant with building a large hotel and visitor attraction. Taking a longer view of history, it is instructive to note that the luxurious Turnberry Hotel (coincidentally, now owned by Trump) on the Ayrshire coast was opened in 1906, just four years after the commissioning of the Ailsa championship course. The majestic Gleneagles Hotel near Auchterarder, in central Scotland, was opened by the Caledonia Railway Company in 1924, five years after the opening of the King’s Course and the Queen’s Course.

Yet even had the applicant sought to resist the imposition of such a condition, a consideration of the law suggests that his avenues for challenge would have been limited. First, the applicant could have argued that the condition was unreasonable. However, given that the condition would have been included to ensure that the impact on the SSSI would be offset by the delivery of the promised hotel, chalets and time-share units, it is difficult to see such an argument succeeding.

Second, under s 33(2)(c) of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 the applicant could have submitted a planning application to have the condition removed. He would probably have chosen to do this prior to the construction of the golf course since he would have had more negotiation leverage then than during or after construction. But again, this action would undermine the claims about the project’s economic credentials. Had the golf course opened without the hotel, time-share units and golf chalets in flagrant breach of the law, the Council could have used its enforcement powers to secure termination of its operation until such time as the accompanying elements had been constructed (s 127 Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997). The developer could appeal against an enforcement notice but if the Planning Reporter/Minister considered that the condition still served a legitimate planning purpose, then it is likely that an appeal would fail. In the event that the developer ignored any planning enforcement notices, the Council could then have applied to the court for an injunction prohibiting any further use of the course until the hotel was built. Any breach of an injunction would place the developer in contempt of court and thus liable to criminal proceedings.

Third, the applicant could have appealed to the Scottish Minister against the condition within three months of determining the application (s 47(a) Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997). However, this would have incurred significant risk since the decision maker hears the case afresh and has the authority to refuse the whole scheme (the golf course, the hotel, the chalets, the time-share units and the housing). Whilst obviously speculative, it seems reasonable to believe that the Minister would not have agreed to the lifting of the condition given that the Government’s tacit support was predicated upon the delivery of the economic benefits from the whole scheme. Further, if the evidence presented had amounted to an admission that the hotel and the other commercial elements were not economically viable, then there would have been a genuine possibility that the entire scheme would have been rejected.

So, given the potency that such a condition might have had, why was it not attached? One might contend that as a ‘street-level bureaucrat’ the planning officer used her discretionary powers to omit such a condition so as to minimise the risk of being blamed for lost investment in the event of the applicant taking umbrage and walking away. Such an argument does not bear scrutiny. According to information provided by the Council, such a condition was simply not considered. As we shall see, the Planning Reporters also failed to consider the matter in their final report to the Minister.

Thus, the planning officer failed to contemplate a scenario in which the applicant did not necessarily plan on completing the proposed development. Given the ambitious scale of the proposed project and the acknowledged disturbance to the SSSI, it was incumbent upon the planning officer to investigate thoroughly the applicant’s track record of completing large developments. Had the planning officer anticipated this as a possibility and incorporated an appropriate condition, then the risk of a great planning disaster on the Aberdeenshire coast would have been reduced and possibly averted.

5.2 The determination of the planning application

Due to its decision to hold a hearing at which members of the public could express their views on the project to the councillors, the consideration of the planning application by Aberdeenshire Council’s Formartine Area committee was deferred from 18 September 2007 to 20 November 2007. The committee voted to support the application 7–4, but also to refer it to the council’s more senior Infrastructure Services Committee for final determination. At that meeting held 29 November 2007, the Director of Planning told the councillors that the scheme would be subject to ‘very stringent conditions … including several to control the phasing of development to ensure that the whole [author’s emphasis] development was delivered’. The vote on the motion to refuse planning permission resulted in a 7–7 tie with the Committee Chairman, Councillor Ford, using his casting vote in line with the convention of supporting the status quo (i.e. to leave the land as it was) and refuse planning permission. In response, the applicant lobbied the First Minister who agreed, extraordinarily, to call in the application before the council formally issued a refusal notice. The applicant could have exercised his right to appeal a refusal, but for tactical reasons, no doubt, made clear that he would not avail himself of that right but would take his investment elsewhere.

In its evidence at the subsequent public inquiry held June–July 2008, Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) contended that the stabilisation of the dunes would destroy the defining characteristic of the SSSI. Dr Hansom of SNH estimated that nearly all 14 hectares of the bare mobile sand sheet – a ‘jewel in the crown’ of SSSIs in the UK – would be significantly adversely affected through grass planting. Critically, Dr Gore, Director of Planning & Environmental Services at Aberdeenshire Council, reiterated a previous undertaking to councillors that all of the facilities of the resort would be required to justify this impact. In their findings, the Planning Reporters accepted both that the golf course would irreversibly compromise the geomorphological integrity of the SSSI and that the scheme – as an ‘overall package’ – would produce significant economic and social benefits across Scotland. Whilst they held that the damage to the SSSI was not compliant with the Aberdeenshire Local Plan, they held that it was nevertheless compliant with the less demanding policy set out in NPPG 14. Thus, on the basis that the overall project would provide significant economic benefits sufficient to compensate for the environmental damage caused by the golf course, the Planning Reporters recommended, and the Minister agreed, that the application should be approved.

6. THE ANATOMY OF THE GREAT MENIE PLANNING DISASTER

Ten years after the First Minister’s enthusiastic endorsement of the decision to approve the scheme, only one part of Trump’s much lauded £1bn resort – the golf course estimated to have cost around £30m – has materialised. None of the other components are in the offing. Whilst the golf course might not yet have achieved the status claimed by Trump, it has won wide acclaim from industry experts, being ranked 56th best in the world just two years after opening. But its development has been at the cost of irreversible damage to the Foveran Links SSSI, which has not been offset by the promised social and economic benefits cited by the decision makers as justification for their support (to return to Hall, a case of UE). The resort employs no more than about 100 people.

Given that a rational developer would want to implement a planning permission if it would generate profits, we must assume that the scheme as applied for was not economically viable when it was conceived or approved. Of course, the collapse of international oil prices has hit north-east Scotland disproportionately hard, but the proponents of the scheme claimed that this was a project that would help diversify the economic base and insulate the region against such events, rather than be affected by them. Realistically, it might be that such a large hotel requires two or more 18-hole courses – as is the case at Turnberry (two 18-hole golf courses) and Gleneagles (three and a half 18-hole golf courses) – in order to provide sufficient customer footfall. Having previously notified the council that he would not be proceeding with the second course because of a dispute over an offshore wind farm, Trump submitted in March 2015 a ‘proposal of application notice’ for a second golf course, 850 residential units and 1900 holiday units (the latter two of which are in excess of what was approved). But this has not yet materialised into a planning application. Eric Trump – now in charge of the scheme during his father’s US presidential term – stated in July 2017 that he was anticipating commencing construction of the second golf course and hospitality facilities in the near future.

By way of contrast, two other prestigious golf courses have been developed along the Scottish coast at Kingsbarns in Fife (2000) and Castle Stuart near Inverness (2009) – and so helping to meet the need (or demand) for such facilities discussed earlier – without including any land subject to a national environmental designation or any substantial ancillary built development. Other world top-100 ranked links courses, such as Cape Kidnappers in New Zealand, Barnbougle Dunes in Tasmania, Cabot Links in Nova Scotia and Bandon Dunes in Oregon, have also been developed in the last decade or so without compromising national designations or including large-scale parasitic development. In the meantime, the Trumps have, to all intents and purposes, walked away from the Menie project and refocused their investment plans on their subsequent golf course acquisitions at Doonbeg in Ireland, and at Turnberry (Hall’s UR).

Hall contended that the responsibility for the public sector-led great planning disasters that he examined lay with communities, bureaucrats and politicians. All of these agents try to act rationally but nevertheless fail in one way or another to achieve a satisfactory outcome. At the privately funded Menie development, the prevailing rationality was that the economic benefits were more than sufficient to outweigh any environmental costs. Those protestors who questioned the ethics and legitimacy of such a calculation were regarded as irrelevant by a powerful local and national media, and labelled as outsiders opposed to wealth creation.

Bureaucratic failings occurred at the council and government level. These can in part be put down to the structural pressures imposed by neoliberal policies, but they were also due to significant professional failings. The council produced a report that failed to subject the economic claims to sufficient scrutiny and failed to assess the risk of partial completion of the project (Hall’s UE/UR). There was a failure to recognise the full implications of the first economic viability report. The residential element was treated as a windfall site rather than as a new settlement. The applicant’s definition of need was not questioned. Alternative sites were not properly considered. Critically, the decision makers failed to incorporate a condition that might have ensured delivery of the economic benefits that provided the legitimacy for the approval.

Notwithstanding this quite lengthy list of alleged failings, one must assume that the contents of the report properly reflect the views of its named author as required by the planning profession’s code of conduct. However, it would be short-sighted to discount the possibility that peer pressure was exerted on the officer given the importance of the proposal. In 2009, the RTPI commenced an investigation into alleged collusion between the council’s Director of Planning and Environmental Services and the applicant.

At the governmental level, the Minister’s decision that the application be called in following the council vote to refuse planning permission was unprecedented and suggested that the Scottish Government was less than impartial. Trump subsequently claimed that the Minister and the Chief Planner had given him the ‘nod’ that the scheme would be approved. The Planning Reporters also adopted many of the positions within the flawed planning officer’s report and failed to recommend inclusion of a more nuanced phasing condition, notwithstanding their concurrence that all of the social and economic benefits were required to justify the scheme.

The failings within the political community were also very evident. Councillor Ford was removed from his chairmanship of the Infrastructure Services Committee following his casting vote, sending a clear message that anybody standing in the way of such projects risked their political career. At the national level, politicians became starry-eyed over a vanity project. The actions of the First Minister in the aftermath of the council vote were subject to considerable criticism from the wider political community, who contended that they amounted to a breach of the Ministerial Code. Prior to becoming First Minister, Alex Salmond, whose constituency included the Menie Estate, told local voters that he backed Trump’s plans ‘to the hilt’. Whilst a later investigation concluded that the First Minister had not breached the Ministerial Code, it held that he had acted in a ‘cavalier’ way. Finally, the Minister determining the application failed to include a watertight condition and so contributed to the planning disaster.

It is also necessary to consider whether the applicant was in any way responsible for the turn of events. At a time when the sport of golf is suffering from falling levels of participation due to changes in taste (Hall’s UV), the scale of Trump’s proposal was always highly ambitious and almost certainly commercially unrealistic. The hotel would have been one of the largest in Scotland and the inclusion of so many time-share units was in stark contrast to, for example, the 30 units at the renowned Macrihanish Dunes golf course located on the Mull of Kintyre. If the whole project was never realistic, it suggests – in keeping with comments made earlier in this paper – that the majority of the proposal was simply a bluff as a means of securing approval for a standalone golf course which he hoped would one day be a venue for the Open Championship. Consequently, we might add uncertainty of developer’s intention (UI) to Hall’s threefold categorisation when considering private sector proposals. In the next section, I consider what remedies might be available to tackle problems arising from lack of developer commitment or adverse economic circumstances.

7. HOW CAN FUTURE ‘MENIE-STYLE’ PLANNING DISASTERS BE AVOIDED?

In order to secure the anticipated social and economic benefits, a council will want to ensure that any approved development is completed. History is littered with grand architectural schemes that were never brought to full fruition. An obvious risk arises from incomplete development, in particular in sensitive locations, but there will also be a significant downside from non-commencement, such as in inner-city locations where the project might be seen as the catalyst to the area’s much needed economic and social transformation. Many cities will include a site that has been passed from proverbial pillar to post by a succession of developers, each invariably proposing an even more attractive yet more implausible project than the previous one. The Battersea Power Station site in London has been subject to numerous proposals, including one for a Disney-style theme park. When such projects do not materialise, there is an element of disappointment and loss for the local community for the scheme that might have been. But there is also a significant opportunity cost incurred by the city authorities through time wasted in negotiations and determining various regulatory applications, as well as the possible loss arising from uncertainty and destabilisation of an already weak land market. A planning authority might have a compulsory purchase power to take control of land from unwilling developers, but where this is not available or practical the only ‘sanction’ against non-commencement will be the lapse of the planning permission, which, under planning acts in the UK, is after three years.

Where construction has commenced but been brought to a premature halt, councils in Scotland can take action either to force completion of the half-built structure (s 62(2) Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997) or require its demolition (s 71 Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997). But a council has no powers to force construction of those elements of the scheme that have not been commenced. So, to illustrate, a developer with planning permission for 100 houses, building one at a time, can be forced to complete or demolish the partially constructed 23rd house but cannot be compelled to build houses 24 to 100. What a council can do is to take a financial bond from the developer to fund completion of roads and sewers necessary to service the development (s 17 Roads (Scotland) Act 1984) and to fund restoration of land to a satisfactory standard (s 75 Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997). The Minister did impose a requirement for a bond to fund restoration of the land at Menie in the event of non-completion of the championship golf course. But it is doubtful that it would be lawful to require a developer to lodge a bond as a means to ensuring that they commence and complete all scheme components for which they have planning permission.

From the foregoing, it can be seen that a properly drafted condition, as suggested earlier in the paper, could only have ensured completion of the commercial elements at Menie if market conditions had remained buoyant. However, had the developer been forced to abandon construction of the golf course due to an economic downturn, the council would have been powerless to force completion of the entire project. The only effect of serving an s 62 notice would have been to render the half-constructed golf course as unauthorised and so subject to enforcement. Alternatively, it could have invoked restoration through the bond. Moreover, whilst forced demolition of a partially complete structure under s 71 can allow the council to restore the situation to the status quo, clearly this will be less straightforward in situations such as at Menie where the incomplete development has caused irreversible (or difficult to reverse) damage to the environment. So, with these limitations noted, what can be done to minimise the risk caused by non-commencement and, in particular, partial completion of a project?

One obvious means by which a council can assess the risk of non-commencement or partial development is to look at the developer’s track record before granting consent. A number of Trump’s grandiose business projects never got beyond receiving the required development consents. To the dismay of city authorities and would-be purchasers, the visually impressive Trump hotel and condominium schemes in Tampa and New Orleans were cancelled in 2007 and 2011 respectively. Under Scottish law, the identity and track record of the developer is not a material consideration in the determination of a planning application. It is suggested here that applicants for schemes of a certain size, nature or location should be required to demonstrate that they are a ‘fit and proper person’ to carry out the proposed development. Managers of charities in the UK are required to submit themselves to such a test, as are would-be owners of English football league clubs. Previous convictions for offences such as theft or fraud would probably rule out somebody from holding such positions. In the context of planning, a track record of unimplemented, unfinished or unauthorised development would be relevant to such a determination. Indeed, it is instructive to note that, in addition to the scuppered projects already mentioned, Trump has been found to have undertaken a number of unauthorised minor developments at Menie requiring the submission of retrospective planning applications to formalise the position (including one for an ‘oversized’ American flag).

However, because the granting of a planning permission simply confers a right (or a privilege) to develop land, rather than a duty to do so, there is presently little that can be done under public law regulations to force commencement and completion. However, if we were to use some creative latitude and construe the grant of a planning permission as amounting to the formation of a private contract, then the position could be very different. So, if we regarded a development plan allocation as an ‘invitation to treat’, a planning application as an ‘offer’ and a permission as an ‘acceptance’, with planning agreements and any damage to the environment as constituting ‘consideration’ by the developer and community respectively, we can see that we are not that far away from a contractual situation. On this ‘planning as contract’ basis, partial performance by the developer – in particular where the other side (the community) has given consideration in the form of the sacrifice of an environmental asset – would constitute a breach of contract.

At law in Scotland, the remedy of specific implement is conventionally considered as being available to victims of a breach of contract seeking performance, bringing the jurisdiction close to the major systems of Continental Europe. However, in practice such a remedy is rarely granted by the courts, making the Scottish system in this regard de facto indistinguishable from that operated by the courts in England and Wales, where the equivalent equitable remedy of specific performance is also rarely ordered. Thus, in both Scotland and in England/Wales damages is the preferred remedy for breach of contract, with quantum normally based upon loss of bargain (expectation loss). However, quantifying the loss at Menie is highly problematic. One could use the tools from environmental economics such as contingent valuation or hedonic pricing to establish the consideration given by the community through sacrifice of the SSSI, but there would still be problems associated with valuing the lost benefits from non-development since the opportunity to develop would remain for other hotel operators. At Menie, however, it could be argued that the developer has provided none of the benefits in return for the damage to the dunes caused by the construction of the golf course and there is no reason to believe that this situation will change in the foreseeable future. Instead of partial performance, there has been a total failure of consideration, amounting to unjust enrichment by Trump. Unjust enrichment is a legal doctrine to describe a contractual breach in which the defendant receives consideration at the expense of the claimant by virtue of an unjust action. The remedy for unjust enrichment is restitution to take the aggrieved party to the position they were in before the contract was formed. Restitution in this case could mean dismantling the golf course (removing the turf from the sand dunes and digging up the fairways, greens and tees) in the hope that the processes of nature would eventually return the land to its original condition.

If, on the other hand, the court were to award the remedy of specific implement / specific performance, then the breaching party would be required to complete the project. However, it is highly unlikely that a court would make an order requiring construction of the remaining elements since, in practice, this would be unlikely to provide a satisfactory outcome for any party (as summed up in the old maxim, ‘equity will not act in vain’). If there were no market for the hotel and time-share units, such an order would simply lead to the construction of a ghost estate. Indeed, courts in the Republic of Ireland, where ghost estates serve as a legacy of the 2007 financial crash, have refused to make orders of specific performance requiring vendees to complete contracts for the purchase of property since this would simply lead to financial insolvency. Yet, if planning law were to be amended so as to allow a court in Scotland, England or Wales to specify performance (i.e. full completion) by a developer of an unfulfilled planning permission, this would serve as a sobering prospect for applicants and could inject a greater sense of responsibility and temper the scale of speculative proposals.

Such a level of commercial responsibility is required by those companies which successfully bid for licenses to provide mobile telecommunications services in the UK. In return for the conferment of the privilege of a near-monopoly, mobile network operators have been required to expand the physical network of base stations to guarantee coverage of 90% of the UK’s landmass by 2017. Failure to develop the network amounts to a breach of the license and possible revocation. If Trump’s permission at Menie were viewed as a license that required completion, then the failure to deliver all of the components could result in the withdrawal of the privilege of development, the acquisition of the golf course by the council and its sale to another operator willing to complete. The obvious difficulty, of course, is that there may well be no other operators that would take on the project.

Without appropriate enforcement measures, planning authorities will invariably be left with few options other than to hope that economic circumstances eventually become sufficiently propitious to make the approved project, or some acceptable alternative, commercially viable. As stated earlier, leisure resort-style projects will often be the most vulnerable to economic downturns since they depend upon discretionary expenditure which individuals will be quick to reduce. The downturn post-2006, combined with the aforementioned reduced interest in golf, led to the net loss between 2006 and 2015 of nearly one thousand 18-hole courses/golf projects in the USA, with net 225 closures in 2015 alone. Included within the long list is the 400-hectare Indian Ridge Resort in Missouri. It bears striking similarities to Menie in terms of its immediate pre-crash date of conception (2006), its development profile (several hundred time-share condominiums and a hotel anchored by a championship golf course), its projected capital value ($1.6bn) and its adverse impact on the natural landscape (severe hillside erosion through runoff). Today, its abandoned half-built mansions stand as a monument to failed laissez faire land use planning, utterly unrealistic commercial expectations and the absence of any effective regulatory enforcement mechanisms. Similar failed or abandoned golf resort projects litter the Spanish coast, suggesting that once consent is given for development there is little that can be done to force completion. Back in the UK, golf courses at Flaxby (Yorkshire) and Botley Park (Hampshire) built within the last 25 years have already closed to make way for more profitable housing. Each of these cases illustrates just how economically fragile leisure-based developments can be and should remind councils of the need to exercise considerable caution when presented with highly enticing proposals to transform their local economies through golf tourism.

8. CONCLUSION

Intuitively, it may seem harsh to label Menie as a great planning disaster simply because the applicant has not delivered the most visually intrusive elements (a negative planning disaster) of what is a very high quality project. After all, outside the realm of the planning balance sheet, the notion that the addition of a holiday resort and a new town along an escarpment would improve the overall outcome seems difficult to sustain. And whilst the incomplete project continues to be a source of significant embarrassment to the Scottish Government, Menie is certainly not a half-built, abandoned resort such as those at Indian Ridge in Missouri or along the Spanish coast. However, as the Planning Reporters acknowledged, the construction of the golf course has been at the expense of irreversible damage to the SSSI (a positive planning disaster). A spectacular natural dune land has been supplanted by a manicured golfscape. It is probably because it is the environment – and not the taxpayer – that has paid that the Trump debacle has not resulted in greater political fallout.

To protect such sensitive areas, the planning system lays down a policy test that must be satisfied to justify that damage. The Menie case pathology has demonstrated that the decision makers failed to ensure that the required economic benefits from the parasitical components of the project were captured. Whilst Trump was a powerful, experienced and shrewd negotiator, there can be little excuse for the repeated oversight of the decision makers to frame an appropriate condition. Of course, in the event that the region’s economic fortunes do recover sufficiently to allow completion of the project in the not too distant future then, within the sometimes perverse calculus of the planning balance sheet, it would have to be conceded that a disaster would be converted into a success.

To make a repeat of the Menie planning disaster less likely, SSSIs need to be afforded the same level of protection as given to SACs, thus virtually prohibiting any schemes that will cause irreversible damage to critical natural capital such as mobile sand dunes. Since the Habitats Directive has long been transposed into UK legislation, the current level of protection for SACs should be unaffected by Brexit unless a government decides to amend or repeal it at a later date.

But if policy does allow environmental assets to be traded off against economic and social benefits, then it is important that new measures be introduced to reduce the risk of incomplete implementation of major schemes. With the continuing downward pressure on local council capital budgets, planning in Scotland (and the rest of the UK) is becoming quasi-contractual in nature, with landowners increasingly being required to outbid the benefits offered by rivals to secure a development plan allocation and a planning permission. Within this emerging ‘planning as contract’ model, councils should be able to mandate within a planning consent that the developer is obliged to complete the development as proposed within a specified timeframe. The track record of a developer should be added to the list of material considerations, allowing councils to refuse proposals from applicants with poor records of scheme completion. Where schemes are not fully implemented, the law should be changed so as to allow councils to pursue remedies such as damages (through payment of development bonds), restitution and specific performance.

So, given the damning comments of so many informed people, including the former First Minister, who moved with effortless ease from heaping encomium on the project one moment to execration the next, it is considered appropriate to label Trump’s development at Menie as a great planning disaster. Within an increasingly deregulated planning system, other controversial golf and leisure resort proposals are likely to be brought forward in environmentally sensitive locations. These could well end up as incomplete developments if the Scottish Parliament fails to legislate in the manner described above and if professional planners fail to scrutinise such proposals properly and include appropriate conditions.

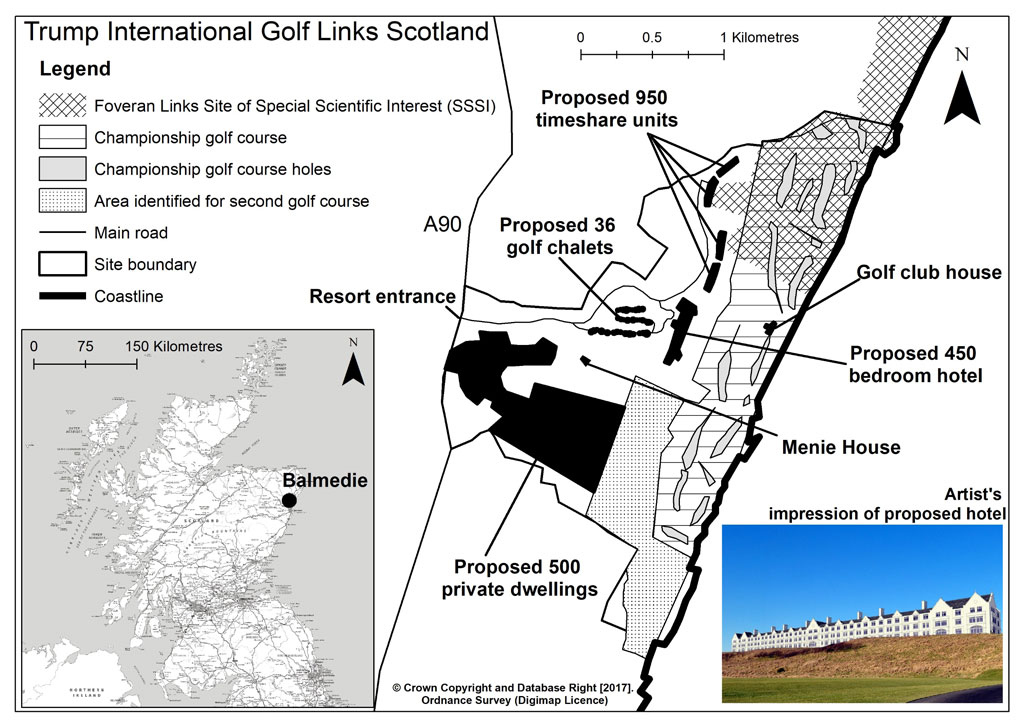

Map of golf links project at Menie.

- 1National Parks, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and Areas of Special Scientific Interest were established through the National Parks and Access to Countryside Act 1949. Areas of Special Scientific Interest were re-labelled as Sites of Special Scientific Interest in the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.

- 2Following the introduction of s 25 of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1991, planning applications are required to be determined in line with the development plan unless material considerations indicate otherwise (see further n 14 regarding the definition of a ‘material consideration’).

- 3Kit Wheeler and John Nauright, ‘A Global Perspective on the Environmental Impact of Golf’ (2006) 9(3) Sport in Society 427; Michael Danielson, Profits and Politics in Paradise: Development of Hilton Head Island (University of South Carolina Press 1995).

- 4The power for decision makers to grant planning permission subject to conditions as they see fit, and for applicants to enter into an agreement with the council to restrict or regulate the use of land, is conferred under, respectively, ss 37(1)(a) and 75(1)(a) of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997.

- 5See s 65(3)(a) Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997.

- 6‘Development’ is defined as ‘… the carrying out of building, engineering, mining or other operations in, on, over or under land or the making of any material change in the use of any buildings or other land…’ (s 26(1) Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997). For the purposes of this paper, the term ‘built development’ refers to the buildings within the plan, such as the hotel, time-share units and private housing, but does not include the golf course.

- 7Eric Jonsson and Guy Baeten, ‘“Because I am who I am and My Mother is Scottish”: Neoliberal Planning and Entrepreneurial Instincts at Trump International Golf Links Scotland’ (2014) 18(1) Space and Polity 54, 65. For an excellent account of the whole Menie saga, see Martin Ford, ‘Deciding the fate of a magical, wild place’ (2011) 4(2) Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies 43.

- 8Peter Hall, Great Planning Disasters (University of California Press 1982).

- 9See further section 3 of the paper.

- 10Unknown, ‘Power line wrangle highlights need for reform’, The Scotsman (21 December 2007); Hamish Macdonell, ‘Why does it take so long?: Scots business chief lambasts “truly shocking” delays in planning system’, The Scotsman (25 February 2008); Hamish Macdonell, ‘Billions lost as economy pays price of planning hold-ups’, The Scotsman (25 February 2008); Hamish Macdonell, ‘Planning row hotel chief: “Small-minded politics costs Scotland jobs”’, The Scotsman (7 March 2008).

- 11Scottish Government, The Government Economic Strategy (Scottish Government 2007).

- 12See Lawrence W.C. Lai, ‘A model of planning by contract: integrating comprehensive state planning, freedom of contract, public participation and fidelity’ (2010) 81(6) Town Planning Review 647; Hing Fung Leung, ‘A legal analysis of the concept of “planning by contract” in non-statutory planning control in Hong Kong’ (2006) 24(5/6) Facilities 211. DOI: 10.1108/02632770610665793.

- 13Hall (n 8).

- 14A ‘material consideration’ was defined by Cooke J as one which ‘… relates to the use and development of land …’ (Stringer v Minister of Housing and Local Government [1970] 1 WLR 1281). As well as the contents of government policy guidance notes (previously labelled as National Planning Policy Guidance notes in Scotland) (R v Poole Borough Council, ex parte Beebee [1991] JPL 643), the courts have held such matters as the availability of alternative sites (Greater London Council v Secretary of State for the Environment [1986] JPL 193) to be a material consideration. The weight to be given to a material consideration in determining a planning application is a matter for the decision maker.

- 15Nathaniel Lichfield, Community Impact Evaluation (UCL Press 1996).

- 16E. C. Grandsen & Co. Ltd v Secretary of State for the Environment [1987] 54 P&CR 86 and Carpets of Worth Ltd v Wyre Forest District Council [1991] 62 P&CR 334. NPPGs were introduced in the 1980s and set out advice on a range of topics such as the preferred location for new housing, industrial and retail developments. They were gradually rebranded as SPPs from the mid 2000s onward as they came up for revision. In 2010, they were consolidated into a single document simply known as Scottish Planning Policy.

- 17Heather Campbell and Malcolm Tait, ‘The Politics of Communication Between Planning Officers and Politicians: The Exercise of Power Through Discourse’ (2000) 32(3) Environment and Planning A 489.

- 18Section 46 Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997.

- 19A ‘Planning Reporter’ is an independent government inspector who adjudicates appeals made to the Minister against refusal. Usually the decision on the appeal is delegated to the Planning Reporter but in the case of large, controversial projects, the Planning Reporter will make a recommendation to the government Minister for his/her decision.

- 20Newbury DC v Secretary of State for the Environment [1981] AC 578.

- 21Scottish Office Development Department, The Use of Conditions in Planning Permissions (Edinburgh, SODD Circular 4/1998).

- 22Scottish Executive, Modernising the Planning System (White Paper 2005).

- 23Deborah Peel and Greg Lloyd, ‘The Twisting Paths to Planning Reform in Scotland’ (2006) 11(2) International Planning Studies 89.

- 24See Jim Cuthbert and Margaret Cuthbert, ‘SNP Economic Strategy: Neo-Liberalism with a Heart’ in Gerry Hassan (ed), The Modern SNP: From Protest to Power (University of Edinburgh Press 2009) 105-119.

- 25Donald Trump, Foreword to David Ewen, Chasing Paradise: Donald Trump and the Battle for the World’s Greatest Golf Course (Black and White Publishing 2010) ix.

- 26Scottish Enterprise Grampian, Menie House Estate Preliminary Feasibility Study (SEG 2006).

- 27Aberdeen City Council and Aberdeenshire Council, North East Scotland Together – Aberdeen / Aberdeenshire Structure Plan (Aberdeen / Aberdeenshire Council 2010); Aberdeenshire Council, Aberdeenshire Local Plan (Aberdeenshire Council 2010).

- 28See the map at the end of this article for the location of the proposed golf links at Menie and the disposition of the various elements of the project. The author is greatly obliged to Ms Emily Forster, formerly of the Department of Geography, Northumbria University, for its preparation.

- 29A much higher level of protection is afforded to certain Special Area of Conservation (SAC) sites designated under the EU Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora Directive (Directive 92/43/EEC; usually abbreviated as the ‘Habitats Directive’). Under Art 6(4) of the Directive, SACs designated as annex I priority natural habitats (such as, for example, coastal dunes with juniperus) can only be subject to building and other operations if these are required for the protection of human health and public safety or for some other imperative reason.

- 30Scottish Executive, Natural Heritage. NPPG 14 (Scottish Executive 2009) / Scottish Natural Heritage, Foveran Links Site of Special Scientific Interest – Management Statement (Scottish Natural Heritage 2002).

- 31Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Councils, Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire Structure Plan: North East Scotland Together (Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Plan Authority 2000), Policy 19: Wildlife, Landscape and Land Resources.

- 32Aberdeenshire Council, Aberdeenshire Local Plan (Aberdeenshire Council 2006), Policy Env\2 National Nature Conservation Sites. See further Clive Spash and Ian Simpson, ‘Protecting Sites of Special Scientific Interest: Intrinsic and Utilitarian Values’, (1993) 39 Journal of Environmental Management 213.

- 33Steve Eder and Alicia Parlapiano, ‘Donald Trump’s ventures began with a lot of hype. Here’s how they turned out’, New York Times (7 October 2016).

- 34Ben Clifford and Mark Tewdwr-Jones, The collaborating planner?: Practitioners in the neoliberal age (Policy Press 2014); Roger Fisher and William Ury, Getting to yes: Negotiating an agreement without giving in (Random House 1981).

- 35As stated earlier, Trump claimed that the project would include the greatest links golf course in the world. Such a statement is perhaps reflective of his approach to trying to secure support from regulatory bodies. In his self-help book on ‘The Art of the Deal’, he states: ‘[m]y style of deal-making is very simple and straight forward. I aim very high, and then I keep pushing and pushing and pushing until I get what I am after. Sometimes I settle for less than I sought but in most cases I still end up with what I want’ (Donald Trump, Donald Trump: The Art of the Deal (Penguin 1987) 45).

- 36cf. David Ewen (n 25).

- 37Aberdeenshire Council, Formartine Area Committee Report (Aberdeenshire Council 18 September 2007). Each planning application submitted to a planning authority is allocated to a case officer whose name is cited in the officer’s report.

- 38Ibid para 2.24.

- 39Ibid para 2.22.

- 40Bent Flyvbjerg, Nils Bruzelius and Werner Rothengatter, Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition (Cambridge University Press 2003).

- 41cf Aberdeenshire Council (n 37) para 6.50.

- 42Ibid para 6.19.

- 43Ibid para 6.48.

- 44Ibid para 6.50.

- 45Ironside Farrar, Golf and Leisure Resort – Menie Estate, Balmedie, Aberdeenshire: Environmental Statement (Ironside Farrar 2007).

- 46cf Aberdeenshire Council (n 37) para 6.55.

- 47Ibid para 6.55.

- 48Ibid para 6.55.

- 49Ibid para 6.55.

- 50Ibid para 11.1.

- 51See South Bucks District Council v Porter [2003] UKHL 26 for the tests to be applied in determining applications for an injunction.

- 52Michael Lipsky, ‘Towards a Theory of Street-Level Bureaucracy’, Institute for Research on Poverty. Discussion Papers (University of Wisconsin 1969).

- 53A response by Aberdeenshire Council to a freedom of information request lodged by the author in April 2014 (Reference ACE/570888) confirmed that there was no record of the council having considered attaching a condition preventing the opening of the championship golf course prior to completion of the hotel.

- 54Aberdeenshire Council, Minute of Infrastructure Service Committee meeting (Aberdeenshire Council 29 November 2007), Item 8, 2nd page.

- 55Rob Edwards, ‘Protests planned and legal action threatened over government intervention in Trump’, Sunday Herald (9 December 2007); David Ross and Robbie Dinwoodie, ‘New chance for Trump’s £1bn resort as ministers call in plan’, Herald (5 December 2007); Editorial, ‘Trump dealings highlight need for probity’, The Scotsman (14 December 2007).

- 56Directorate of Planning and Environmental Appeals, Report to the Scottish Ministers: Application APP/2006/4605 for outline planning permission dated 27 November 2006 called-in from Aberdeenshire Council by notice dated 4 December 2007 – Golf Course and Resort Development (DPEA 2008). Available at <https://www.dpea.scotland.gov.uk/CaseDetails.aspx?ID=105007> (accessed 19 December 2018).

- 57Ibid para. 2.2.43.

- 58Ibid para. 4.105.

- 59Ibid paras. 4.39-4.40.

- 60Scottish Government, News Release: Menie estate golf resort (Scottish Government, 16 December 2008) <http://www.gov.scot/News/Releases/2008/12/16131333> (accessed 27 August 2018).

- 61John Barton, World’s 100 Greatest Golf Courses (Golf Digest 2016); <http://www.golfdigest.com/story/worlds-100-greatest-golf-courses> (accessed 27 August 2018).

- 62Severin Carrell, ‘Donald Trump has lost tens of millions on Scottish golf courses, accounts show’, The Guardian (12 October 2016).

- 63Trump unsuccessfully challenged the lawfulness of the Scottish Government’s decision to approve the Vatenfall offshore windfarm, which he argued would be a visual blight on his project. See Trump International Golf Club Scotland Ltd and another v The Scottish Ministers [2014] UKSC 74. Defeat in the court led him to announce that he would cease all further investment at Menie: see ‘Donald Trump withdraws application for second golf course’, BBC (13 February 2014), <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-26135345> (accessed 27 August 2018).

- 64Jon Hebditch, ‘Game on in north-east as Trump ready for round two’, Press & Journal (21 July 2017).

- 65See Stephen Goodwin, Dream Golf: The Making of Bandon Dunes (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2006). Mike Keiser, the developer of Bandon Dunes, is proposing a championship quality golf course at Coul Links, Embo in Sutherland. Labelled by the press as ‘Trump Mark II’, the 326ha site contains land designated as a SSSI, a SAC, a Special Protected Area and a RAMSAR site: see Rob Edwards, ‘Trump Mk II: now his business rival plans golf course which threatens Scottish environment’, The Herald (21 August 2016). In June 2018, the councillors at Highland Council approved the scheme against the advice of the officers. Following lengthy consideration, the Scottish Government announced in August 2018 that it was calling in the application for its own determination as the proposal raises important issues concerning natural heritage and compliance with national planning policy. See Scott MacLennan, ‘Ministers ‘call in’ Coul Links golf course proposal’, Press & Journal (25 August 2018).

- 66Mike Wade, ‘Trump set for £35m deal to buy Turnberry’, The Times (29 April 2014).

- 67Frank Urquhart, ‘Rejecting Trump’s golf resort “would deter global investment in Scotland”’, The Scotsman (6 December 2007).

- 68Royal Town Planning Institute, Code of Professional Conduct (RTPI 2016).

- 69Rob Edwards, ‘“Collusion” claim against planner at centre of Trump row’, Sunday Herald (15 November 2009). The Royal Town Planning Institute does not ordinarily publicise the results of investigations into allegations of misconduct by members and, for this reason, the outcome of this particular investigation is unknown.

- 70Scottish Parliament Local Government and Communities Committee, Planning Application Processes (Menie Estate) 5th Report 2008 (Session 3) (Scottish Parliament 2008).

- 71Lindsay McIntosh, ‘SNP ministers “told Trump he would win” planning battle over £1bn golfing scheme’, The Times (18 October 2010).

- 72‘Bunkered’, Scotland on Sunday (16 December 2007). Almost a decade after the scheme had been approved, the former First Minister of Scotland stated that he would not have supported it had he known that the promised economic benefits would not be delivered: Alex Salmond, ‘The Mad World of Donald Trump’, Channel 4 (26 January 2016); <http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x3ov6db> (accessed 11 August 2017).

- 73Scottish Parliament Local Government and Communities Committee, Planning Application Processes (Menie Estate) 5th Report 2008 (Session 3), Scottish Parliament 2008. Simon Johnson, ‘Alex Salmond “cavalier” in Trump dealings’, The Telegraph (14 March 2008).

- 74‘The Future of Golf: Handicapped’, The Economist (20 December 2014), <http://www.economist.com/news/christmas-specials/21636688-though-thriving-parts-asia-golf-struggling-america-and-much-europe> (accessed 27 August 2018).

- 75Macrihanish Dunes golf course incorporates land designated as a SSSI. Southworth Development LLC states that it works in close collaboration with Scottish Natural Heritage and refrains from using chemical fertilisers on the course: See: <http://machrihanishdunes.com/wp-ontent/uploads/2015/05/MachDunes_Consumer.pdf> (accessed 27 August 2018).

- 76For example, a new railway-connected holiday resort town was planned by the Peak Estate Company at Ravenscar on the North Yorkshire coast in the 1890s. In an episode having obvious parallels with Trump’s Menie project, a hotel and golf course were built (and remain) but a planned new town never materialised. See also Mark Osbaldeston, Unbuilt Toronto: A History of the City That Might Have Been (Dundurn 2008).

- 77Scottish Ministers, ‘Minister’s decision letter for golf resort at Menie’, 16 December 2008. See Annex / Condition 8(ii). <https://www.dpea.scotland.gov.uk/CaseDetails.aspx?ID=105007> (accessed 27 August 2018).

- 78See Susan Taylor Martin, ‘Buyers still feel burned by Donald Trump after Tampa tower condo failure’, Tampa Bay Times (31 July 2015) and Mike Scott, ‘Whatever happened to Donald Trump’s plan for a Trump Tower New Orleans?’, The Times-Picayune (17 June 2016).

- 79Finance Act 2010; Schedule 6, Part I, s 4.

- 80‘Donald Trump wins Menie golf course flag pole wrangle’, BBC (15 November 2015), <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-37986345> (accessed 27 August 2018).

- 81See the concluding chapter ‘Future Glory?’ in Philip Booth, Planning by Consent: The Origins and Nature of British Development Control (Routledge 2003) for a discussion over the lack of potency of current enforcement mechanisms to ensure completion of developments, and the potential benefits of an alternative system using landlord and tenant rules.

- 82Tellingly, submissions by developers for development allocations in draft local plans (known as a ‘Main Issues Report’) are referred to as ‘bids’.

- 83Contract law in Scotland differs slightly from its English counterpart: see generally Martin Hogg, Obligations (2nd edn., Avizandum 2006). Perhaps most notably, Scots law operates with a doctrine of ‘promise’ by which one can enter into a legally binding unilateral obligation through a mere promise, without the need for consideration: see e.g. Petrie v Earl of Airlie [1834] 13 S 68; W. D. H. Sellar, ‘Promise’ in Kenneth Reid and Reinhard Zimmermann (eds), A History of Private Law in Scotland: Volume 2: Obligations (Oxford University Press 2000) 252, 273–275.

- 84See Kier Construction Ltd v W. M. Saunders Partnership LLP [2016] CSOH 17.

- 85See e.g. Robinson v Harman [1848] 1 Ex 850. Cost of cure and loss of amenity are also available as remedies for breaches of contract (see e.g. Ruxley Electronics and Construction Ltd v Forsyth [1995] UKHL 8). One could argue that the council could make a claim for loss of amenity through incomplete performance of the planning permission at Menie with damages being returned to the public by way of reduced property taxes.

- 86Contingent valuation derives monetary values for non-traded goods – such as sand dunes – through survey questionnaires in which members of the public are asked how much, hypothetically (hence ‘contingent’), they would be willing to pay to secure the protection of such assets (or accept as compensation for their destruction). In contrast, hedonic pricing compares actual transaction prices of goods (such as two identical houses, one of which overlooks a park with the other overlooking a factory) to derive residual environmental values. See Nick Hanley, Jason Shogren and Ben White, Introduction to Environmental Economics (Oxford University Press 2013). These techniques were explored in further detail by the EU when devising its Environmental Liability Directive (Directive 2004/35/CE on environmental liability with regard to the prevention and remedying of environmental damage (OJ 2004 L143/56)). See also MacAlister Elliot and Partners Ltd and the Economics for the Environment Consultancy Ltd, Study on the Valuation and Restoration of Damage to Natural Environmental Resources for the Purposes of Environmental Liability (MacAlister Elliot and Partners 2001), available at <http://ec.europa.eu/environment/legal/liability/pdf/biodiversity_main.pdf> (last accessed 27 August 2018).

- 87See further e.g. Peter Birks, Unjust Enrichment (Oxford University Press 2004); Lipkin Gorman v Karpnale Ltd [1988] UKHL 12.

- 88See Aranbel Limited v Darcy and others [2010] IECH 272.

- 89Ofcom, ‘Ofcom varies mobile operators’ licences to improve coverage’, 2nd February 2015. <https://www.ofcom.org.uk/about-ofcom/latest/media/media-releases/2015/mno-variations> (accessed 26th September 2017).

- 90National Golf Foundation, Golf Facilities in the U.S. – 2016 (National Golf Foundation 2016).

- 91Cliff Sain,‘More details in fraud case related to failed Indian Ridge development’, Branson News (27 January 2017) <http://bransontrilakesnews.com/news_free/article_61dfedce-e4d5-11e6-bbb7-1b6f392522eb.html> (accessed 27 August 2018). In November 2011, Indian Ridge Resort, Inc was found guilty of violating the Federal Clean Water Act through uncontrolled runoff from 250 hectares of cleared land from August 2006 to June 2009, and fined USD 215,000. <https://cfpub.epa.gov/compliance/criminal_prosecution/index.cfm?action=3&prosecution_summary_id=2287> (accessed 27 August 2018).

- 92Santiago Munoz and Luis Cueto, ‘What has happened in Spain? The real estate bubble, corruption and housing development: A view from the local level’ (2017) 85(4) Geoforum 206.

- 93Rosemary Ayim, ‘The growing trend to build houses on golf courses’, The Golf Business (10 April 2015), <http://www.thegolfbusiness.co.uk/2015/04/the-growing-trend-to-build-housing-on-golf-courses/> (accessed 27 August 2018).

- 94Scottish Natural Heritage, the Scottish Government’s nature watchdog, has confirmed that the construction of the golf course has partially destroyed the dune system protected under the SSSI designation. See Robin McKie, ‘Trump golf resort wrecked special nature site, reports reveal’, The Guardian (29 July 2018).

- 95The Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010: No. 490 and The Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017: No. 1012.