Dual Attribution of Conduct to both an International Organisation and a Member State

Stian Øby Johansen

Associate Professor, Centre for European Law, University of Oslo

s.o.johansen@jus.uio.noPublisert 20.12.2019, Oslo Law Review 2019/3, Årgang 6, side 178-197

Responsibility, and in particular attribution of conduct, is one of the most intensely debated issues of public international law in the last couple of decades. In this article I seek to determine whether, how, and when acts or omissions may be attributed both to an international organisation and a member State (dual attribution). My aim is to clarify what dual attribution is, and what it is not. This is done in two steps. First, I (a) define the concept of dual attribution, (b) demonstrate that dual attribution is possible under the current law of international responsibility, and (c) establish a typology of dual attribution. Second, dual attribution is distinguished from three forms of shared responsibility. These are situations of two acts or omissions leading to one injury, derived responsibility, and the notion of piercing the corporate veil of international organisation. I end the article by criticising the disproportionate attention given to dual attribution in legal scholarship, given its limited practical utility.

Keywords

- international responsibility

- dual attribution

- shared responsibility

1. Introduction

Responsibility has long been one of the most hotly debated topics of international law. The debate became particularly intense following the completion by the International Law Commission (ILC) of its Articles of State Responsibility for Internationally Wrongful Acts (ARS) in 2001, and its Articles on the Responsibility of International Organizations (ARIO) in 2011.

One issue that has received particular attention is the intermingling of States and International Organisations (IOs) in cases where this leads to internationally wrongful acts. Internationally wrongful acts are constituted by two elements: (a) the attribution of a course of conduct to a State/IO that (b) entails a breach of an international obligation of that State/IO. In particular, the element of attribution has been extensively discussed in the literature.

The rules on attribution deal with a classic problem of law: legal persons – such as States and International Organisations – do not have hands or minds of their own. They therefore depend on physical persons of flesh and blood to act on their behalf. In international law, the rules on attribution of conduct determine when an act or omission of a person is considered as the act or omission of a State and/or an IO.

Attribution raises difficult issues even when only a single State or IO is involved, but particular questions arise when States and IOs act in concert: Can one course of conduct be attributed to both an IO and a State simultaneously? When and under what conditions may such dual attribution occur? And how does dual attribution relate to other situations where two international legal persons are jointly responsible towards a third person (shared responsibility)? Those are the core questions that I will discuss in this article.

In doing so, my principal aim is to clarify what dual attribution is, and what it is not. While there is plenty of literature on both dual attribution and its false friends, these are often specialised studies that examine only one or a couple of types of shared responsibility, or articles debating particular aspects of the rules on attribution. Often they assume so much from the reader that those who are not experts on the law of international responsibility will struggle to understand the relationship between the different types of shared responsibility.

This article attempts to consolidate these studies and discussions into a coherent system. The methodology I use for system-building is traditional, legal-dogmatic analysis. This article is in other words neither novel in its methodology, nor in its analysis of individual legal issues. What this article instead adds to the body of knowledge is a pedagogic systematization of a complex, yet increasingly important area of international law. Additionally, since dual attribution’s false friends are included in this systematisation exercise, I also demonstrate that dual attribution is more obscure than the great academic interest in the concept would suggest.

I will first approach the topic in positive terms, in order to identify what dual attribution is, in section 2. In doing so, I will first briefly explain the function of attribution in the law of international responsibility (section 2.1–2.2). Then I establish a conceptual skeleton of dual attribution (section 2.3), before presenting arguments for why dual attribution is possible under current international law (section 2.4). I end this part with a typology of dual attribution (section 2.5).

Following this definition and analysis, I turn to distinguishing it from three forms of shared responsibility that are easily confused with dual attribution in section 3. In other words, this section is about what dual attribution is not.

In section 4, I conclude by arguing that dual attribution has received disproportionate attention in the literature, given its limited utility in practice. Conversely, the three forms of shared responsibility outlined in section 3 have received scant attention – despite their greater promise of practical utility.

2. What dual attribution is

2.1 Attribution and the codification of the law of international responsibility

States and IOs are legal persons, ie corporate entities. They do not take on a physical form, and thus cannot act on their own. The idea of a State or an IO as ‘an acting person is not a reality but an auxiliary construction of legal thinking’. Rather, natural persons – people of flesh and blood – act on their behalf. Attribution rules are therefore a logical necessity. Indeed, as argued by Ahlborn, ‘attribution of conduct to corporate actors is crucial for their very existence’.

The ILC has sought to codify the rules on attribution as part of its project to codify the law of international responsibility. The ARS have generally been welcomed by the international community. Although not formally binding, they are considered ‘in whole or in large part an accurate codification of the customary international law of State responsibility’. The reactions to the ARIO were more mixed. Many criticized the ILC for using a copy-paste approach when drawing up the ARIO by drawing direct analogies from the ARS. This is inappropriate – the critics argue – because ‘International Organizations are definitively not states’.

While a complete assessment of the international legal status of the rules contained in the ARIO is beyond the scope of this article, my view is that the criticism of the ARIO is overstated, perhaps even misguided. While it is true that IOs are clearly not States, they belong to the same umbrella category: international legal persons. And, as explained above, attribution rules are inherent to the very concept of legal persons.

Since attribution rules are inherent to the very notion of a legal person, the only international legal question is their content. The rules of attribution contained in the ARS are an accurate codification of the customary international law of State responsibility. On the other hand, due to the lack of practice, customary attribution rules may be lacking for IOs. Yet, since rules on attribution must exist, it seems entirely appropriate to draw analogies from the rules on attribution applicable to the only other type of autonomous legal person in the international legal system: States. Some adaptations will necessarily have to be made – since IOs are not States – but there is no cogent reason why the attribution rules have to be radically different. In this article I will therefore presume that the relevant provisions of the ARIO reflect general international law.

2.2 Attribution is concerned with conduct

In international law, attribution rules are concerned with conduct. Conduct is an umbrella term that includes both acts and omissions. That said, I will sometimes use the term ‘act’ interchangeably with ‘conduct’ in this article, because the verb form of conduct and the noun ‘conductor’ is not used in international legal literature. By this use of terms I do not, however, intend to downplay the crucial role that omissions play in establishing international responsibility.

Since attribution rules are concerned with conduct, the right question to ask when applying them to a factual scenario is the following: can a course of conduct performed by X (the direct actor) be attributed to Y (a State or an IO)?

That a particular course of conduct is attributable to a State/IO does not necessarily imply that the State/IO in question has violated international law. Indeed, attribution of conduct to a State/IO is only the first of two conditions for international responsibility – the second is that the conduct in question violates the international obligation(s) of that State/IO. Nevertheless, some scholars use the term ‘attribution of violations’ as shorthand for attribution of conduct constituting an internationally wrongful act.

Adding to the potential for terminological confusion, other scholars use the term ‘attribution of violations’ as an umbrella term for forms of responsibility in connection with the conduct of others – eg aid and assistance, coercion, so-called circumvention, etc. The defining feature of these forms of responsibility is that the responsibility of Y for its own conduct arises only because it has a particular connection with a certain conduct of X. Such forms of responsibility are also referred to by scholars using other, more or less confusing umbrella terms: ‘secondary responsibility’, ‘indirect responsibility’, ‘derived responsibility’, or ‘attribution of responsibility’. In this article I use the term derived responsibility for these forms of shared responsibility. Below, in section 3.3, I will discuss derived responsibility further, and distinguish it from dual attribution.

2.3 Dual attribution as a concept

Dual attribution means the simultaneous attribution of one act or omission (a course of conduct) to two international legal persons – for example an IO and a member State. In this article I will only discuss situations of dual attribution involving an IO and a member State. This is due to the close and complex relationship between IOs and member States. They cooperate and collaborate in many different ways, and the distribution of tasks and competences between IOs and their member States vary immensely.

Such complexities invite discussions of dual attribution and shared responsibility. That said, dual attribution is not conceptually limited to IO-member State relations. It could also apply to other pairings: two States, two IOs, or an IO and a non-member State. Thus, I will draw some analogies from case law concerning other pairings than that of an IO and a member State.

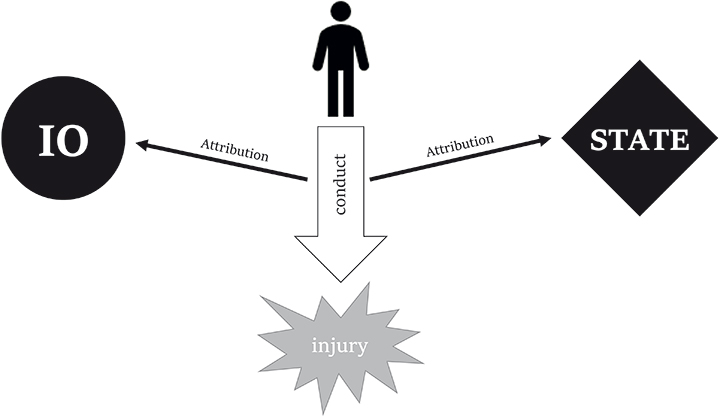

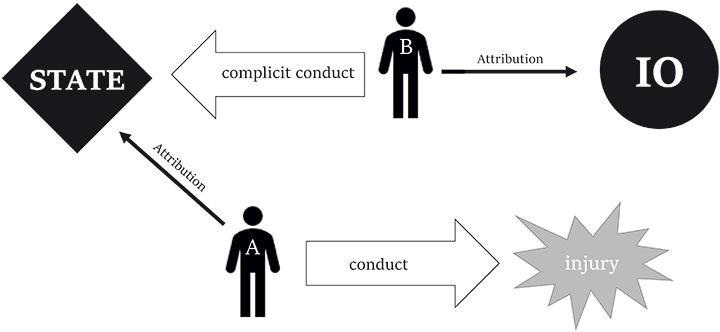

The concept of dual attribution may be illustrated as follows:

Figure 1

An abstract illustration of dual attribution.

The keystone of dual attribution is the single course of conduct – one act or omission. Usually, there will also be only one person involved. In some instances, however, more than one person may be involved in performing what must be legally characterised as a single act. There may be situations where two or more persons collaborate so closely that their conduct is indistinguishable. This may be the case when common organs are established. Moreover, when omissions are involved, there is often a plurality of persons that have failed to act. For example, the ICJ found that Iran had violated the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations by failing to protect the US embassy in Tehran from attacks in 1979. There is no single Iranian official this omission was attributed to. Rather, the ICJ attributed this omission to ‘the Iranian Government’ and ‘Iranian authorities’, ie large swathes of the Iranian executive branch and security apparatus.

The single course of conduct is simultaneously attributed to both a State and an IO. That course of conduct may entail the responsibility of both the State and the IO. But, since States and IOs are not always bound by the same (primary) legal obligations, it may happen that an act attributed jointly to a State and an IO only entails the responsibility of one of them. This could, for example, occur if the act entails the breach of a treaty obligation, since States are party to far more (and often different) treaties than IOs.

The abstract illustration of the concept of dual attribution above can easily be turned into a practical example:

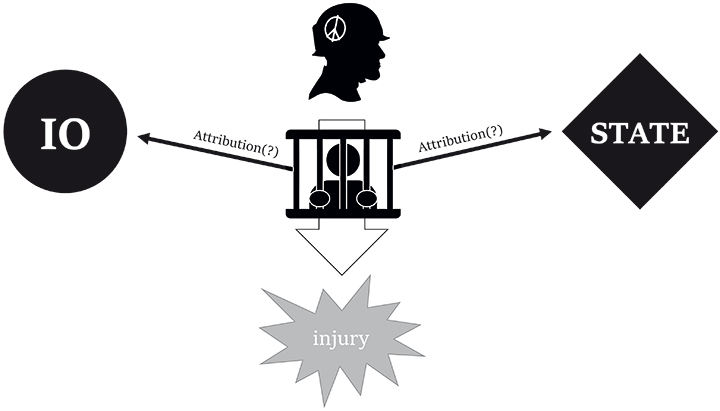

Figure 2

An illustration of a situation where dual attribution may occur.

Figure 2 shows a possible situation of dual attribution where peacekeeping troops (represented by the person wearing a helmet with the peace sign) have acted by detaining a person. The act of detaining (represented by the illustration of a detainee) is the course of conduct.

Even though peace missions are subsidiary organs of the IO in charge, their troops are not employed directly by the organisation, but are rather seconded to it from its member States. States are reluctant to give up complete control over its military forces. When they second troops to peace missions, they therefore never transfer complete command and control over their troops. Troop-contributing States routinely retain disciplinary authority and the right to withdraw troops at any time. Usually there are also additional limitations on the transfer of command, known as ‘caveats’.

If the formal arrangements are not complex enough, the practical exercise of command and control over IO-led missions is even more convoluted:

[R]eality does not always match what was formally agreed … States occasionally intervene in the operational management of their troops in contravention with the agreed distribution of command and control, thereby undermining the authority of the UN Force Commander.

Such meddling is not a UN-specific phenomenon, but rather a staple of military missions (ostensibly) commanded by IOs. NATO missions are characterised by complex webs of national caveats, the ‘red card’ procedure, and unanimous operational decision-making by the North Atlantic Council. EU Common Foreign and Defence Policy missions are similarly impaired by a complex sharing of command and control, extensive national caveats, and meddling by troop-contributing States.

With such complex formal relationships of authority, intermingled conduct, and meddling by troop-contributing States, who is responsible for the troops? The UN or the troop-contributing State? Is the onus of untangling these complexities, in order to identify the correct respondent for a claim, on the injured party?

Perhaps attribution does not have to be a binary – either/or – choice. Perhaps one could attribute the conduct to both the IO and the State. This is the essence of the concept of dual attribution: one act or omission that is simultaneously attributable to both an IO and a State.

Whether such dual attribution is legally possible depends on the rules of attribution. If the attribution rules are formulated in a way that forces binary (either/or) solutions, dual attribution is impossible. On the other hand, if they do not force such binary choices, dual attribution should be possible.

2.4 Dual attribution as lex lata

2.4.1 Introduction

To move from the conceptual level to positive law, I will analyse the rules of attribution under current international law in order to demonstrate that they allow for dual attribution – despite some indications to the contrary from the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).

2.4.2 The pertinent bases of attribution: organic link and control

In the dual attribution context, two bases of attribution are of particular interest:

-

Attribution of conduct due to an organic link between an organ or agent and the State/IO.

-

Attribution of conduct due to control by the State/IO over the direct actor.

It is important to distinguish between organic link and control-based attribution. That is because the scope of the conduct that is attributed to the State/IO varies between these two categories.

Attribution based on an organic link happens en bloc : all the conduct of organs and agents are attributed to the State/IO they belong to. Even if an organ or agent exceeds its authority or contravenes instructions its conduct is nevertheless attributed to the State or IO. There is only a very limited exception to this default rule: so-called ‘private’ or ‘off-duty’ conduct is not attributed. For example, if a UN staff member working in New York City decides to rob a bank while off work, that robbery is not attributable to the UN.

On the other hand, attribution based on control is ad hoc in the sense that control must be exercised over each particular course of conduct. Attribution based on control must therefore, in principle, be determined on a case-by-case basis. Non-attribution is in other words the default rule; ‘effective control’ over a particular course of conduct must be proven for attribution to happen.

What qualifies as an organ or agent differs slightly between States and IOs. An organ of a State ‘exercises legislative, executive, judicial or any other functions, whatever position it holds in the organization of the State, and whatever its character as an organ of the central Government or of a territorial unit’. The term ‘organ’ is here understood in a broad sense – as any natural or legal person, including individual officials, departments, executive agencies, and other bodies. A single police officer is thus an organ, and so is a collective body such as a committee, a court, or a legislature. State organs not only include those that have such status according to the laws of that State, but also de facto organs. Thus, a State ‘cannot evade responsibility … merely by denying [an organ] the status as such under internal law’. The test for when a person or entity qualifies as a de facto organ is strict: ‘complete dependence’ on the State, in the sense that they are merely an instrument of that State, is required. In addition, the conduct of persons or entities that are neither de lege nor de facto organs, but which are empowered by domestic law to ‘exercise elements of the governmental authority’, is attributed to the State under an organic link (en bloc).

An organ of an IO may be defined as any component of the organisation that, according to the rules of the organisation, performs some of its functions. There is little need to precisely delimit what constitutes an IO organ since the conduct of agents of the organisation is also attributed to it under an organic link (en bloc). The term ‘agent’ must be understood ‘in the most liberal sense’. Any person or other non-organ entity ‘who is charged by the organization with carrying out, or helping to carry out, one of its functions, and thus through whom the organization acts’ is regarded as an agent. In exceptional circumstances IO functions may be regarded as given to an organ or agent even if this is not based on the rules of the organisation (de facto organs and agents).

This concept of an agent distinguishes the rules on attribution of conduct to IOs from those applicable to States. There is no parallel to ARS Article 8 (discussed in the next paragraph), which allows for the attribution of the conduct of private persons to IOs if the organisation exercises effective control over that conduct. However, the concept of an IO agent is broad and inclusive, and captures many of the situations that for States are attributed based on ARS Article 8. When private individuals act under the direction or control of an IO, they may usually be regarded as agents of the organisations. The difference between the two regimes may therefore not be significant with regard to whose conduct may be attributed, but the extent of the conduct that may be attributed is quite different: the conduct of private individuals regarded as agents is attributed to an IO under an organic link (en bloc), while the conduct of private individuals is only attributed to a State when there is effective control over a particular act or omission (ad hoc).

Attribution may also be based on the control exercised by a State or an IO over the conduct of private persons or other entities. The conduct of private individuals is attributed to a State if it exercises effective control over the particular conduct of those individuals. Similarly, the conduct of a State organ placed at the disposal of an IO is attributed to the IO if it exercises effective control over the conduct of that organ. While the test of control is phrased identically, as ‘effective control’, the field of application of ARIO Article 7 is narrower than ARS Article 8. ARIO Article 7 only envisages the possibility of effective control over the conduct of an organ of a State. In contrast, the conduct of private individuals may be attributed to States if they exercise effective control over them.

Since ARIO Article 7 applies when IOs control State organs, it must first be distinguished from the organic link rule in ARIO Article 6. The dividing line is the degree to which authority is transferred: if a State organ is ‘fully seconded’ to an IO, it must be regarded as a (de facto) organ of that IO. Conversely, ARIO Article 7 applies when the organ in question is still a State organ that has merely been ‘placed at the disposal of’ an IO. The conduct of that State organ will then be attributed to the IO if the latter exercises effective control over the conduct in question.

Whether the control test under ARIO Article 7 has been met must be determined on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the actual exercise of control over the State organ in question. The threshold is lower than the requirement of effective control under ARS Article 8. The notion of control in ARIO Article 7 is ‘intimately linked’ to the military notion of operational (command and) control. When operational control over a State organ is transferred to an IO, there is a presumption that the organ’s conduct is attributed to the organisation. At least so with regard to the functions of the IO that the seconded State organ exercises on the organisation’s behalf. This presumption is rebuttable. According to Zwanenburg:

This presumption can be rebutted if it is established that the [State organ] acted under the direction and control of the [seconding] state, the clearest example of which would be specific instructions. The mere provision in agreements between the [IO] and [seconding] states that national administrative matters remain the responsibility of the government of the troop contributing state, or that the orders of the international commander are received by the contingent through the national operational commander of the contingent, do not establish such a situation [ie a rebuttal].

2.4.3 The current attribution rules allow for dual attribution

There is nothing in the rules of attribution analysed just above that excludes dual attribution. Attribution is the result of a legal evaluation, and the attribution rules are not mutually exclusive. Thus, as Boutin puts it: ‘[b]ecause attribution operates individually, parallel attribution of a given conduct can arise if grounds for attribution are found for each entity.’

Although the attribution rules seem to allow for dual attribution, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) apparently rejected the very notion of dual attribution in its (in)famous 2007 Behrami and Saramati decision. The facts pertaining to Mr Saramati illustrates the case well: he was first detained for a month on suspicion of attempted murder, but then released after the Supreme Court granted his appeal against the decision to extend his pre-trial detention. Soon after his release, however, Mr Saramati was detained anew by the UN Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) police on the order of the Commander of the Kosovo Force (KFOR), who at the time was a Norwegian military officer. This second period of detention was not pre-trial detention, however, but rather security detention – ie preventive detention purely for the purpose of establishing a secure environment in Kosovo. After just over six months in security detention, Mr Saramati was convicted of attempted murder by the District Court and transferred to the UNMIK detention facilities – thus ending his security detention. The conviction was later quashed by the Supreme Court, and Mr Saramati was released pending a re-trial in the District Court.

Mr Saramati alleged that he had been held in extra-judicial detention by KFOR for over six months without access to a court, and brought a case before the ECtHR against France, Germany, and Norway. The choice of respondents is explained by the fact that the commander of KFOR at the time of his arrest was a Norwegian officer. A French officer then took over as commander of KFOR while Mr Saramati was still in security detention. Moreover, Mr Saramati initially alleged that a German soldier had been involved in his second arrest, but later withdrew the case against Germany because he could not put forward any objective evidence in support of the allegation.

The first issue that the ECtHR had to tackle was whether the conduct of the (Norwegian and French) officers was attributable to the UN, to their home States, or both. In its decision, the ECtHR found that the detention of Mr Saramati was attributable to the United Nations, because KFOR was ‘exercising lawfully delegated Chapter VII powers’. Then – without much real explanation – the Court added that the conduct in question could not be attributed to the respondent States. Although the court never says it explicitly, this hasty conclusion seems premised on the view that attribution is a binary (either/or) question.

The Behrami and Saramati decision was fiercely criticised by scholars on exactly this point. Larsen described the Court’s approach as ‘difficult to reconcile with’ the ILC’s work on the responsibility of international organisations, with UN practice on responsibility for unlawful conduct in peace operations, and with the ECtHR’s own jurisprudence concerning attribution of conduct.

Ten years have passed since Behrami and Saramati, and the world has moved on. And it has moved in the direction of accepting dual attribution. First, domestic courts have rejected Behrami and Saramati, and accepted dual attribution in recent rulings. The House of Lords (now: UK Supreme Court) arguably rejected Behrami and Saramati in Al-Jedda, which was decided just months after Behrami and Saramati. Moreover, Dutch courts have repeatedly confirmed the possibility of dual attribution in cases concerning the acts of Dutch peacekeeping troops in connection with the Srebrenica genocide. German courts also appear to have recognized the possibility of dual attribution in the MV Courier litigation.

Second, the ILC distanced itself from Behrami and Saramati in the commentaries to ARIO. The ILC also explicitly recognized the possibility of dual attribution, although it added that ‘it may not frequently occur in practice’.

Third, even the ECtHR itself appears to have moved on, by reversing Behrami and Saramati. The most explicit reversal may be found in its 2011 judgment in the Al-Jedda case. The case concerned the internment of Mr Al-Jedda in Iraq by British forces. The UK argued, inter alia, that the internment was attributable to the United Nations, and thus ipso facto not to the UK. However, in its judgment, the ECtHR rejected the UK’s argument:

The Court does not consider that … the acts of soldiers within the Multi-National Force became attributable to the United Nations or – more importantly, for the purposes of this case – ceased to be attributable to the troop-contributing nations.

This confirms the conclusion reached at the start of this section, namely that dual attribution is indeed possible, lex lata.

2.5 A typology of dual attribution

2.5.1 Overview

Dual attribution can occur in a multitude of situations. It may be useful to distinguish between situations of dual attribution by virtue of the four possible pairings of organic link and control-based attribution:

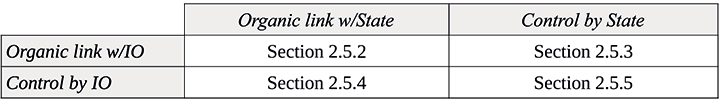

Table 1

A typology of dual attribution.

2.5.2 Double organic link

The classic example of a double organic link is common organs. These are a fairly common occurrence in legal relations between IOs inter se. Common organs are also exceptionally established between States. When a common organ is established by two States or IOs, that organ’s conduct is attributed to them both, since there is a double organic link. The same must apply to an organ that is common to a State and an IO.

In addition, we have the situation briefly mentioned above in section 2.3 where the conduct of two persons is so closely intertwined to be indistinguishable. Consider, for example, a situation where a State official and an IO official perform a collective act or omission. Generally, the conduct of each of them is attributable to the State/IO under an organic link. Since their conduct is collective, it must be simultaneously attributed to the IO and the State in question. Again, there is a single course of conduct (one act or omission) that is attributed to both a State and an IO, because of a double organic link.

2.5.3 Organic link with an IO and exercise of control by a State

Dual attribution may also occur when a person who is organically linked to an IO is simultaneously being instructed by a State. Such situations of dual attribution typically arise when States interfere with the activities of an IO’s organs or agents.

A hypothetical example of such interference could be that an UNHCR agent handling resettlement applications from refugees is recruited as a spy by a State. The agent in question then copies and transfers sensitive personal data about the refugees whose applications he handles to that State. This irregular collection of personal data is attributable to the UNHCR through the organic link, since the agent is acting under apparent authority, while exercising UNHCR functions. At the same time, this irregular data collection is attributable to the State, which exercises effective control over the agent performing it. One course of conduct is thus attributable to both an IO and a State.

2.5.4 Organic link with a State and effective control by an IO

A third situation could be when the conduct of an organ is attributable both to a State under an organic link and simultaneously to an IO that exercised effective control over that conduct. For dual attribution to arise in such situations, the attribution rules in ARS Article 4 (cf. Article 7) and ARIO Article 7 must be capable of being applied concurrently. However, the ILC appears to envisage ARIO Article 7 as an either/or attribution rule. At least that is how the commentaries to the provision are phrased: ‘the condition for attribution of conduct either to the contributing State … or to the receiving organization is based … on the factual control that is exercised’.

Moreover, as mentioned above in section 2.4.2, there is no direct equivalent of ARS Article 8 in the ARIO. ARIO Article 7 appears similar, but is more closely related to ARS Article 5, since it concerns control over State organs that are placed at the disposal of an IO. By definition, then, ARIO Article 7 is only applied in situations where the person or entity performing the conduct is a State organ. When ARIO Article 7 applies, it functions as an exception from the general rule that the conduct of State organs is attributable to the State. Instead, as long as the organ is placed at the disposal of an IO that also exercises effective control over it, attribution is exclusive to the IO. Conversely, in the absence of effective control by the IO over a particular course of conduct, only the organic link rule in ARS Article 4 applies.

That said, it might not be possible to completely rule out dual attribution of conduct in these situations. Palchetti suggests that dual attribution could exceptionally be possible in cases ‘where it is not clear whether the national contingent was acting in the exercise of functions of the sending state or of the organization.’ One example he mentions is where the conduct was the result of instructions given by mutual agreement of the IO and the State. Palchetti also mentions the case of the evacuation of Dutchbat from Srebrenica:

[In] the transition period following the fall of Srebrenica, it was hard to draw a clear distinction between the power of the Netherlands to withdraw Dutchbat from Bosnia and the power of the UN to decide about the evacuation of the UNPROFOR unit from Srebrenica. Since during that period both the Netherlands and the UN appeared to be formally entitled to exercise their respective powers over Dutchbat, and since in fact they both exercised their actual control by issuing specific instructions, dual attribution might be regarded as justified.

2.5.5 Concurrent effective control

It is difficult to envisage dual attribution resulting from concurrent effective control by an IO and a State. That is because the field of application of the two control rules are different. As mentioned, ARIO Article 7 only allows for the attribution of the conduct of State organs placed at the disposal of, and under effective control of, an IO to that organization. In contrast, the conduct of private persons under the effective control of a State is attributed to that State under ARS Article 8. There does not appear to be any overlap between these two control rules that may give rise to dual attribution.

Still, one must not forget that the notion of agent of an IO is understood quite broadly, as any person through whom the organisation acts. This means that situations that for States would fall under the control rule in ARS Article 8, for IOs would be discussed under the notion of an IO agent, and thus under the organic link rule in ARIO Article 4. This is very similar to the situation where the conduct of a private person is simultaneously attributed to two States due to their concurrent effective control. However, there is a crucial difference: the attribution to the IO happens due to an organic link – meaning that also ultra vires conduct is attributable. It is thus probably better to categorise such cases as situations where there is an organic link with an IO and effective control by a State (see above, section 2.5.3).

3. What dual attribution is not

3.1 Introduction

Having defined and explained what dual attribution is, what remains is to distinguish it from situations of shared responsibility that are similar to – but distinct from – dual attribution.

Dual attribution and shared responsibility are not synonyms. Rather, dual attribution is merely one of several bases upon which an IO and a member State may share responsibility. To the untrained eye these may appear similar to dual attribution, and are often confused with it.

Three such forms of shared responsibility that are easily confused with dual attribution will be discussed in the following:

-

Two distinct acts/omissions, one injury (section 3.2)

-

Derived responsibility (section 3.3)

-

‘Piercing the veil’ (section 3.4)

At the outset of this exercise in comparing and contrasting, it is worth reiterating the distinguishing feature of dual attribution: one act or omission that is simultaneously attributable to both an IO and a State.

3.2 Two acts or omissions, one injury

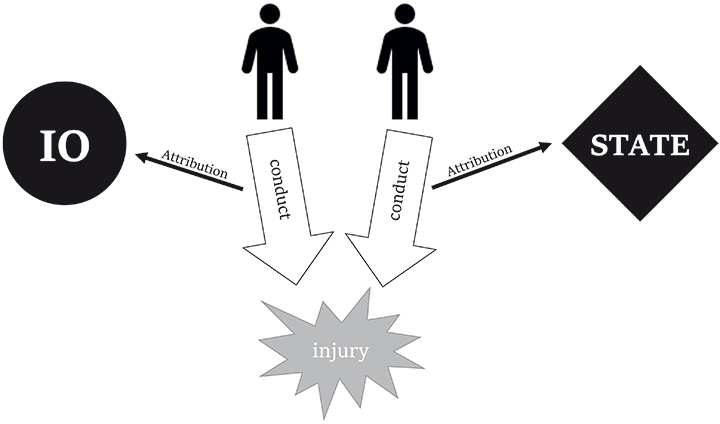

The first of these forms of shared responsibility is the situation where two concurrent but distinct courses of conduct give rise to the same injury. This may be illustrated as follows:

Figure 3

Two courses of conduct that cause one injury.

As you can see from the illustration (Figure 3), two persons are acting – each performing a separate act. The conduct of person A is attributable to an IO. The conduct of person B is attributable to the State. This is thus not an instance of dual attribution. There are two acts, each attributable to a single State/IO.

This situation may be illustrated by a case before the ECtHR that involved two States: MSS. v Belgium and Greece. This case concerned an asylum seeker that had entered the European Union (EU) through Greece. He then made his way to Belgium, and applied for asylum there. However, Belgian authorities chose to return him to Greece, as is permitted under the Dublin regulation. Upon arrival in Greece, the asylum seeker was detained in conditions that amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment. Furthermore, the Greek asylum procedure was so deficient, and the living conditions for asylum seekers so poor, that it entailed further violations of the prohibition against inhuman and degrading treatment.

The ECtHR held that Greece was responsible for the treatment of the asylum seeker while in Greece. It was Greek State organs that had mistreated him, and that failed to provide him with a functioning asylum procedure. However, the Court also found Belgium responsible for refoulement – ie for sending the asylum seeker back to Greece, thus exposing him to inhuman and degrading treatment. Thus, there were two distinct sets of acts and omissions that were attributable, respectively, to Greece and Belgium. None of the acts or omissions were attributable to both States.

3.3 Derived responsibility

The second form of shared responsibility that is sometimes confused with dual attribution is what the ILC terms ‘[r]esponsibility … in connection with the act of another’. As already mentioned above in section 2.2, I will refer to this using the less convoluted term derived responsibility. There are four closely related, and sometimes overlapping, types of derived responsibility:

-

Aid and assistance (ARS Article 16; ARIO Articles 14 and 58).

-

Direction and control (ARS Article 17; ARIO Articles 15 and 59).

-

Coercion (ARS Article 18; ARIO Articles 16 and 60).

-

Circumvention (ARIO Articles 17 and 61).

The common thread among them is that one international legal person (typically the IO) in some way influences another international legal person (typically the State) to conduct itself in a particular way. An IO may, for instance, enact a binding rule that a member State is obliged to follow; or an IO may provide resources to a State in support of a particular course of conduct on the part of that State.

All four forms of derived responsibility may thus be illustrated as follows:

Figure 4

Derived responsibility.

In this illustration (Figure 4) the conduct that directly causes the injury is performed by a State official (A). In addition, a separate course of conduct – which I will term the complicit conduct – is performed by an agent of an IO (B). The complicit act takes different forms, depending on the type of derived responsibility:

-

The IO may aid and assist a member State, eg by providing support to a military unit under the command of a member State.112. ARIO commentaries, Article 14, para 6.

-

The IO may direct and control the conduct of a member State, eg by adopting decisions that the member States are obliged to execute.113. ARIO commentaries, Article 15, para 4.

-

The IO may coerce a member State, ie by creating a situation comparable to force majeure, although this is probably impractical.114. ARIO commentaries, Article 16, para 4; ARS commentaries, Article 18, paras 2–4.

-

The IO may circumvent one of its obligations, eg by adopting a decision that requires member States to perform an act that would be unlawful for the organisation.115. Circumvention may thus overlap with direction and control, at least partially. See ARIO commentaries, Article 15, para 5.

Regardless of the form the complicit conduct takes, it remains that we are faced with two separate courses of conduct. One act that directly causes the injury, and is attributable to the State. Another, a distinct act of complicity, is attributable to the IO. This situation is clearly distinguishable from dual attribution: there are two courses of conduct, neither of which are attributable to more than one international legal person.

The facts of the well-known case of Bosphorus Airways v Ireland may serve as a practical example of derived responsibility. That case concerned the impounding of an aircraft by Irish authorities. The act of impounding the aircraft was thus attributable to Ireland under an organic link. Bosphorus Airways, who had leased the aircraft from Yugoslav Airlines, alleged that the impoundment violated their right to property under ECHR Protocol 1, Article 1. Ireland defended its actions by pointing out that it was obliged to impound due to an EU regulation ordering the impoundment of, inter alia, all aircraft belonging to the then State of Yugoslavia – the aircraft’s (indirect) owner.

The legal obligation to impound followed from an EU regulation enacted by the Council. Since the Council is an organ of the EU, its decision to enact the regulation was attributable to the Union. On the other hand, the physical act of impounding the aircraft was done by Irish officials at Dublin Airport, on instructions from the Irish Government. The impoundment was therefore attributable to Ireland – and not to the EU. According to the terms used just above, the impoundment is the act that directly causes the injury, while the decision to enact the regulation is the complicit conduct.

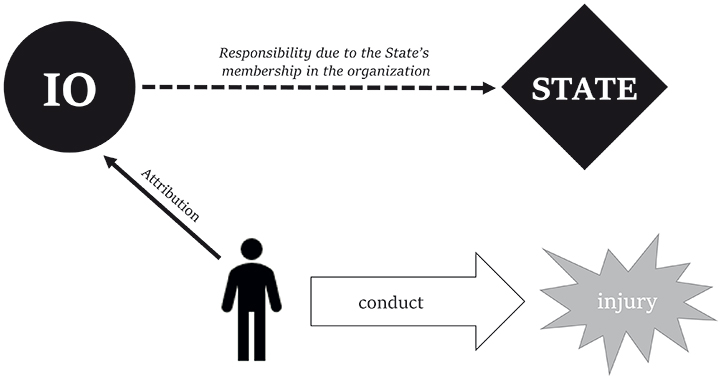

3.4 Piercing the (corporate) veil

The third form of shared responsibility that may be confused with dual attribution is the notion of ‘piercing the veil’. It may be illustrated as follows:

Figure 5

Piercing the corporate veil of an international organisation.

In this illustration (Figure 5) there is only one act or omission, which is attributable to an IO. The State is not acting – or, more precisely, no one is acting on the behalf of the State. The idea is rather that the State would be responsible for any violations that the IO has committed simply on the basis of its membership of the organisation. To ‘pierce the veil’ is thus clearly not a form of dual attribution.

Moreover, there is a lack of support for veil-piercing in international law. This theory is probably inspired by national legal systems, some of which allow for lawsuits that ‘pierce the corporate veil’ of limited liability companies by allowing lawsuits against stock holders. However, there is no support for this notion in international law. Variants of the veil-piercing argument have been made on multiple occasions before both domestic and international courts, and it has consistently been rejected. And, while the ARIO Article 62 concerns the responsibility of a member State for ‘for an internationally wrongful act of that organization’, it only envisages responsibility where the member State has expressly ‘accepted responsibility’ for a particular course of conduct or ‘led the injured party to rely on its responsibility’.

4. Conclusion: What role for dual attribution?

Having thoroughly defined dual attribution, and distinguished it from three forms of shared responsibility, it is worth taking a step back to consider the overall role dual attribution plays in the law of international responsibility. One conclusion that materialises out of the detailed analysis is that although dual attribution is possible, it is more obscure than the great academic interest in it would suggest. It is probably only possible in a very narrow set of circumstances. It is a rather rare phenomenon, and the strict conditions required will rarely be fulfilled in typical cases where IOs and their member States act in concert.

Only in the rare instances where there is a dual attribution of conduct to an IO and a member State, shared responsibility may arise – provided that the conduct attributed to them constitutes a breach of the international legal obligations of them both. In other words, shared responsibility based on dual attribution of conduct does not appear to be the most prominent source of shared responsibility in cases of concerted action of IOs and their member States – far from it. Forms of shared responsibility, particularly derived responsibility, appear more suitable for application to situations where IOs and their member States act in concert. In particular, aid and assistance may be useful for holding both IOs and member States jointly responsible for peacekeeping troops – thus alleviating the need for the complex analysis of whether the organisation exercised sufficient control under ARIO Article 7.

Despite its promise, aid and assistance has traditionally received markedly less attention than dual attribution. Although there has been a slight uptick in scholarly interest in the last decade, case law is lacking. Indeed, we are still waiting for the first case before an international court where aid and assistance is argued up-front-and-centre. A thorough discussion of whether derived responsibility and other forms of shared responsibility in practice could displace responsibility based on dual attribution is therefore a natural next step. However, that would require an article of its own.

- 1This is an updated, refocused and expanded version of my trial lecture for the degree of PhD, originally held on 16 June 2017. Thanks to Hilde K Ellingsen and Sofie A E Høgestøl for feedback on the trial lecture manuscript, and to OsLaw’s anonymous reviewer for helpful comments.

- 2Annexed to UN General Assembly resolution 56/83 (28 January 2002) UN Doc A/RES/56/83, and corrected by UN Doc A/56/49(Vol. I)/Corr.4.

- 3Annexed to UN General Assembly resolution 66/100 (27 February 2012) UN Doc A/RES/66/100.

- 4ARS, Article 2; ARIO, Article 4.

- 5To mention just a few prominent works on attribution published in the last decade: James Crawford, Alain Pellet and Simon Olleson (eds), The Law of International Responsibility (OUP 2010) chapters 17–22 <https://doi.org/10.1093/law/9780199296972.001.0001>; Aurel Sari and Ramses A Wessel, ‘International Responsibility for EU Military Operations: Finding the EU’s Place in the Global Accountability Regime’ in Bart Van Vooren, Steven Blockmans and Jan Wouters (eds), The EU’s Role in Global Governance (OUP 2013) 126 <https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199659654.003.0009>; James Crawford, State Responsibility: The General Part (CUP 2013) chapters 4–6 <https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139033060>; Francesco Messineo, ‘Attribution of Conduct’ in André Nollkaemper and Ilias Plakokefalos (eds), Principles of Shared Responsibility in International Law: An Appraisal of the State of the Art (CUP 2014) 60 <https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139940009.004>; Paolo Palchetti, ‘International Responsibility for Conduct of UN Peacekeeping Forces: The Question of Attribution’ (2015) 36 Seqüência: Estudos Jurídicos e Políticos 19; Bérénice Boutin, ‘The Role of Control in Allocating International Responsibility in Collaborative Military Operations’ (PhD thesis, University of Amsterdam 2015); Tom Dannenbaum, ‘Dual Attribution in the Context of Military Operations’ (2015) 12 International Organizations Law Review 401 <https://doi.org/10.1163/15723747-01202007>; Andre Nollkaemper and Ilias Plakokefalos (eds), The Practice of Shared Responsibility in International Law (CUP 2017) <https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316227480>; Yohei Okada, ‘Effective Control Test at the Interface between the Law of International Responsibility and the Law of International Organizations: Managing Concerns over the Attribution of UN Peacekeepers’ Conduct to Troop-Contributing Nations’ (2019) 32 Leiden Journal of International Law 275 <https://doi.org/10.1017/s0922156519000062>.

- 6Brigitte Stern, ‘The Elements of an Internationally Wrongful Act’ in James Crawford, Alain Pellet and Simon Olleson (eds), The Law of International Responsibility (OUP 2010) 193, 202.

- 7Christiane Ahlborn, ‘To Share or Not to Share? The Allocation of Responsibility between International Organizations and Their Member States’ (2013) 88 Die Friedens-Warte 45, 48.

- 8Ibid.

- 9On the use of terminology (dual v multiple attribution), see footnote 41.

- 10I use this term analogously. Its original meaning is: ‘a word or expression in one language which has the same or similar form in another, but which does not have a corresponding meaning’; see the entry for ‘false’ in Oxford English Dictionary online (draft additions, September 2016) <www.oed.com/view/Entry/67884> accessed on 12 July 2019.

- 11On system-building as a task of legal scholarship, see Jan M Smits, ‘What Is Legal Doctrine? On the Aims and Methods of Legal-Dogmatic Research’ in Rob van Gestel, Hans-W Micklitz and Edward L Rubin (eds), Rethinking Legal Scholarship (CUP 2017) 207 <https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316442906.006>.

- 12Hans Kelsen, Pure Theory of Law (Max Knight tr, 2nd edn, Lawbook Exchange 1967) 292.

- 13Ahlborn (n 7) 48.

- 14Ibid.

- 15Crawford (n 5) 43.

- 16See eg: the survey of comments made by States and IOs on the first reading of ARIO in Giorgio Gaja, ‘Eighth Report of the Special Rapporteur on Responsibility of International Organizations’ (2011) UN Doc A/CN.4/640, 5 (para 5); Gerhard Hafner, ‘Is the Topic of Responsibility of International Organizations Ripe for Codification? Some Critical Remarks’ in Ulrich Fastenrath and others (eds), From Bilateralism to Community Interest (OUP 2011) 695 <https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199588817.003.0044>; Jan Wouters and Jed Odermatt, ‘Are All International Organizations Created Equal?’ (2012) 9 International Organizations Law Review 7 <https://doi.org/10.1163/15723747-00901016>; Aurel Sari, ‘UN Peacekeeping Operations and Article 7 ARIO: The Missing Link’ (2012) 9 International Organizations Law Review 77 <https://doi.org/10.1163/15723747-00901013>.

- 17Wouters and Odermatt (n 16) 13.

- 18Alain Pellet, ‘International Organizations Are Definitively Not States: Cursory Remarks on the ILC Articles on the Responsibility of International Organizations’ in Maurizio Ragazzi (ed), Responsibility of International Organizations: Essays in memory of Sir Ian Brownlie (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers 2013) 41 <https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004256088_005>.

- 19Crawford (n 5) 43.

- 20On the lack of practice, see Hafner (n 16), particularly at 700–704.

- 21See generally Fernando Lusa Bordin, The Analogy between States and International Organizations (CUP 2018) chapter 2 <https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316658963>.

- 22Similarly: Christiane Ahlborn, ‘The Use of Analogies in Drafting the Articles on the Responsibility of International Organizations: An Appraisal of the “Copy-Paste Approach”’ (2012) 9 International Organizations Law Review 53 <https://doi.org/10.1163/15723747-00901001>.

- 23ARS, Article 2; ARIO, Article 4.

- 24For an example of how omissions may be attributed, see below in section 2.3.

- 25ARS, Article 2; ARIO, Article 4.

- 26See eg: Guido Acquaviva, ‘Human Rights Violations before International Tribunals: Reflections on Responsibility of International Organizations’ (2007) 20 Leiden Journal of International Law 613, 615–617 <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156507004281>; Róisín Burke, ‘Attribution of Responsibility: Sexual Abuse and Exploitation, and Effective Control of Blue Helmets’ (2012) 16 Journal of International Peacekeeping 1 <https://doi.org/10.1163/187541111x613597>; Ottavio Quirico, ‘The International Responsibility of the European Union: A Basic Interpretive Pattern’ (2013) Hungarian Yearbook of International Law and European Law 63, 72.

- 27Examples include: Giorgio Gaja, ‘Second report on responsibility of international organizations’ (2 April 2004) UN Doc A/CN.4/541, para 12; Paolo Palchetti, ‘Applying the Rules of Attribution in Complex Scenarios: The Case of Partnerships among International Organizations’ (2016) 13 International Organizations Law Review 37 <https://doi.org/10.1163/15723747-01301003>; James D Fry, ‘Attribution of Responsibility’ in André Nollkaemper and Ilias Plakokefalos (eds), Principles of Shared Responsibility in International Law: An Appraisal of the State of the Art (CUP 2014) 98, particularly at 113–127 <https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139940009.005>.

- 28Boutin (n 5) 149.

- 29Crawford (n 5) ch 12; Boutin (n 5) 146–148, with further references.

- 30Boutin (n 5) 149.

- 31Messineo (n 5) 67 and 79–80. Similarly: Melanie Fink, Frontex and Human Rights: Responsibility in ‘Multi-Actor Situations’ Under the ECHR and EU Public Liability Law (OUP 2018) 104.

- 32Fink (n 31) 104–105.

- 33ICJ, United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran (United States v Iran) [1980] ICJ Rep 3, paras 61–68.

- 34Ibid, particularly paras 63–65.

- 35See eg the comments by the UN Office of Legal Affairs in ‘Responsibility of international organizations: Comments and observations received from international organizations’ (17 February 2011) UN Doc. A/CN.4/637/Add.1, at 13–14.

- 36Ibid at 14 (para 4); Boutin (n 5) 39. For examples of such caveats, see Dannenbaum (n 5) 422; Efthymios Papastavridis, ‘EUNAVFOR Operation Atalanta off Somalia: The EU in Unchartered Legal Waters?’ (2015) 64 International & Comparative Law Quarterly 533, 555 <https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020589315000214>; David Nauta, The International Responsibility of NATO and Its Personnel during Military Operations (Brill 2017) 162 <https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004354647>.

- 37Boutin (n 5) 38; Nauta (n 36) 161.

- 38Boutin (n 5) 39 (footnotes omitted).

- 39Ibid 40–42; Nauta (n 36) 78–79 and 161–162.

- 40Papastavridis (n 36), particularly at 555-556; Stian Øby Johansen, ‘The Human Rights Accountability Mechanisms of International Organizations: A Framework and Three Case Studies’ (PhD thesis, University of Oslo 2017) 150–153, with further references.

- 41If dual attribution is possible, then, in theory, a course of conduct could potentially also be attributed to more than two international legal persons (multiple attribution). However, this is a quite impractical hypothesis. Indeed, one may even question the practical utility of dual attribution, as I do in section 4. In this article I will thus only discuss dual attribution. However, most of the points made should be applicable mutatis mutandis to multiple attribution.

- 42ARS, Articles 4–7; ARIO, Articles 6 and 8.

- 43ARS, Article 8; ARIO, Article 7.

- 44ARS, Article 4; ARIO, Article 6(1).

- 45ARS, Article 7; ARIO, Article 8.

- 46Commentaries to the ARS, published in ‘Report of the International Law Commission on the work of its Fifty-third session’ (2001) UN Doc A/56/10 (hereafter referred to as ‘ARS commentaries’), Article 7, paras 3–8, with further references; Commentaries to the ARIO, published in ‘Report of the International Law Commission on the work of its Sixty-third session’ (2011) UN Doc A/66/10 (hereafter referred to as ‘ARIO commentaries’). Article 8, para 9; UN Office of Legal Affairs, ‘Memorandum on Liability of the United Nations for Claims Involving Off-Duty Acts of Members of Peace-Keeping Forces’ in UN Juridical Yearbook (1986) 300.

- 47ARS, Article 8 if ; ARIO, Article 7 if.

- 48ARS, Article 8; ICJ, Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v United States) [1986] ICJ Rep 14 para 115; ARIO, Article 7.

- 49ARS, Article 4(1).

- 50ARS, Article 4(2); ARS commentaries, Article 4, para 12.

- 51ARS commentaries, Article 4, para 11; Djamchid Momtaz, ‘State Organs and Entities Empowered to Exercise Elements of Governmental Authority’ in James Crawford, Alain Pellet and Simon Olleson (eds), The Law of International Responsibility (OUP 2010) 237, 243.

- 52Crawford (n 5) 124–125.

- 53ICJ, Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v Serbia) [2007] ICJ Rep 43 paras 391–393. See also ibid 123–126.

- 54ARS, Article 5.

- 55ARIO, Article 6(1).

- 56ICJ, Reparation for injuries suffered in the service of the United Nations (Advisory Opinion) [1949] ICJ Rep 174 at 177.

- 57ARIO, Article 2(d). See also ibid and ICJ, Difference Relating to Immunity from Legal Process of a Special Rapporteur of the Commission on Human Rights (Advisory Opinion) [1999] ICJ Rep 62 para 66.

- 58ARIO commentaries, Article 6, para 9.

- 59ARIO commentaries, Article 6, para 11.

- 60This is well illustrated in Fink (n 31) 104 (Table 3.1).

- 61ARS, Article 8; ICJ, Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v United States) [1986] ICJ Rep 14 para 115.

- 62ARIO, Article 7.

- 63There is in other words a clear difference between the two sets of Draft Articles on this point. See Blanca Montejo, ‘The Notion of “Effective Control” under the Articles on the Responsibility of International Organizations’ in Maurizio Ragazzi (ed), Responsibility of International Organizations: Essays in memory of Sir Ian Brownlie (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers 2013) 389 <https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004256088_033>.

- 64ARIO commentaries, Article 7, para 1.

- 65As emphasized by Pierre d’Argent, ‘State Organs Placed at the Disposal of the UN, Effective Control, Wrongful Abstention and Dual Attribution of Conduct’ (2014) 1 Questions of International Law 17.

- 66ARIO commentaries, Article 7, para 4.

- 67Palchetti (n 27) 36–38; Okada (n 5) 267 and 279–281. On the ‘effective control’ threshold in ARS article 8, see in particular: Olivier de Frouville, ‘Attribution of Conduct to the State: Private Individuals’ in James Crawford, Alain Pellet and Simon Olleson (eds), The Law of International Responsibility (OUP 2010) 257; Crawford (n 5) chapter 5; Boutin (n 5).

- 68ARIO commentaries, Article 7, para 10; Montejo (n 63) 393; Johansen (n 40) 58–59.

- 69Marten Zwanenburg, Accountability of Peace Support Operations (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers 2005) 102; Okada (n 5) 276–277; Palchetti (n 5) 39–40. But see contra: Dannenbaum (n 5).

- 70Palchetti (n 5) 39; Okada (n 5) 282–288.

- 71Zwanenburg (n 69) 102–103.

- 72Messineo (n 5) 70 and 82.

- 73Boutin (n 5).

- 74ECtHR, Behrami and Behrami v France, and Saramati v France, Germany and Norway [GC] (dec.), no 1412/01 & 78166/01 (2007).

- 75KFOR is a so-called international security presence established by UN Security Council resolution 1244 and agreements between NATO military authorities and the now extinct Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The tasks given to KFOR in the resolution were broad, and included deterring hostilities, establishing secure environments for refugees to return home, and ensuring public safety in a transitional period.

- 76ECtHR, Behrami and Behrami v France, and Saramati v France, Germany and Norway [GC] (dec.), no 1412/01 & 78166/01 (2007) para 11. The KFOR Legal Adviser considered that KFOR had the authority to make use of security detention under UN Security Council resolution 1244.

- 77ECtHR, Behrami and Behrami v France, and Saramati v France, Germany and Norway [GC] (dec.), no 1412/01 & 78166/01 (2007) para 9.

- 78Ibid, para 15.

- 79Ibid, para 64.

- 80Ibid, paras 140 and 143.

- 81Ibid, para 151.

- 82See eg: Marko Milanović and Tatjana Papić, ‘As Bad as It Gets: The European Court of Human Rights’s Behrami and Saramati Decision and General International Law’ (2009) 58 International & Comparative Law Quarterly 267 <https://doi.org/10.1017/s002058930900102x>; Kjetil Mujezinović Larsen, ‘Attribution of Conduct in Peace Operations: The “Ultimate Authority and Control” Test’ (2008) 19 European Journal of International Law 509 <https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chn029>; Aurel Sari, ‘Jurisdiction and International Responsibility in Peace Support Operations: The Behrami and Saramati Cases’ (2008) 8 Human Rights Law Review 151 <https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngm046>.

- 83Larsen (n 82), particularly at 520–530.

- 84UK House of Lords, R (Al-Jedda) v Secretary of State for Defence [2007] UKHL 58. The Lords were somewhat diplomatic in the sense that they distinguished Behrami and Saramati on the facts; see Marko Milanović, ‘Al-Skeini and Al-Jedda in Strasbourg’ (2012) 23 European Journal of International Law 121, 135 <https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chr102>.

- 85Dutch Supreme Court (Hoge Raad), Netherlands v Nuhanović [2013] ECLI:NL:HR:2013:BZ9225; Dutch Supreme Court (Hoge Raad), Netherlands v Mustafić et.al. [2013] ECLI:NL:PHR:2013:BZ9228; Dutch Supreme Court (Hoge Raad), Netherlands v Mothers of Srebrenica et.al. [2019] ECLI:NL:PHR:2019:95. For a detailed analysis of the Nuhanović and Mustafić cases, see André Nollkaemper, ‘Dual Attribution: Liability of the Netherlands for Conduct of Dutchbat in Srebrenica’ (2011) 9 Journal of International Criminal Justice 1143 <https://doi.org/10.1093/jicj/mqr048>; Christine Bakker, ‘Dual Arbitration of Acts Committed by a UN Peacekeeping Force: An Emerging Norm of Customary International Law: The Dutch Supreme Court’s Judgments in Nuhanović and Mustafić’ (2013) 23 Italian Yearbook of International Law 287 <https://doi.org/10.1163/22116133-90230048>.

- 86Cologne Administrative Tribunal, judgment 25 K 4280/09 (2011) ILDC 1808 (DE 2011), particularly para 68. The judgment was upheld on appeal in Higher Administrative Court of Nordrhein-Westfalen, judgment 4 A 2948/11 (2014) ILDC 2391 (DE 2014), although with a reasoning that was much less clear on the issue of attribution. See Emanuele Sommario, ‘Attribution of Conduct in the Framework of CSDP Missions: Reflections on a Recent Judgment by the Higher Administrative Court of Nordrhein-Westfalen’ (2016) CLEER Papers 2016/5, 171–172.

- 87ARIO commentaries, Article 7, paras 10–12.

- 88ARIO commentaries, Article 7, para 4.

- 89ECtHR, Al-Jedda v UK [GC], no 27021/08 (2011).

- 90Ibid para 80 (emphasis added). See also Milanović (n 84) 136.

- 91Henry G Schermers and Niels M Blokker, International Institutional Law: Unity within Diversity (6th ed, Brill Nijhoff 2018) 1159–1163. Examples include the World Food Programme (a common organ of the UN and FAO) and the Codex Alimentarius Commission (a common organ of the FAO and WHO).

- 92A prominent example is the Channel Tunnel Intergovernmental Commission, a common organ of the UK and France.

- 93Crawford (n 5) 340; ARS commentaries, article 47 para 2; Roberto Ago, ’Seventh report on State responsibility’, ILC Yearbook 1978/II(1) at 31, 54; ICJ, Phosphate Lands in Nauru (Nauru v Australia) [1992] ICJ Rep 240 paras 45–48; Eurotunnel Arbitration (Partial Award of 30 January 2007) para 179.

- 94To be absolutely clear: the State official is not seconded to the IO in this scenario. Rather, both officials are acting under the exclusive authority of their respective State and IO.

- 95The fact that the irregular part of the data collection, ie the transfer of copies of the collected data to the State, is ultra vires from the perspective of the UNHCR does not matter. See ARIO, Article 8; Giorgio Gaja, ‘Second report on responsibility of international organizations’ (2 April 2004) UN Doc A/CN.4/541 paras 54–57; Okada (n 5) 252.

- 96ARIO commentaries, Article 7, para 4 (emphasis added).

- 97Messineo (n 5) 83–84 and 91–93.

- 98d’Argent (n 65) 27.

- 99Palchetti (n 5) 48–49.

- 100Ibid 49.

- 101Ibid (footnote omitted).

- 102ARIO, Article 2(d).

- 103See Messineo (n 5) 78 for some possible examples of dual attribution to States under ARS Article 8.

- 104I use the term ‘injury’ in a wide sense, similarly to how Nollkaemper and Jacobs use the term ‘harmful outcome’ in ‘Shared Responsibility in International Law: A Conceptual Framework’ (2012) 34 Michigan Journal of International Law 359, 367.

- 105ECtHR, MSS v Belgium and Greece [GC], no 30696/09 (2011).

- 106The applicable regulation at the time was Council Regulation (EC) 343/2003 (‘Dublin II’) [2003] OJ L50/1.

- 107ECtHR, MSS v Belgium and Greece [GC], no 30696/09 (2011) paras 9–34 and 225–234.

- 108Ibid, paras 35–37, 41–52, 249–264, and 286–321.

- 109Ibid, paras 340, 344–360, and 362–368.

- 110ARS chapter IV; ARIO chapter IV.

- 111Berenice Boutin, ‘Responsibility in Connection with the Conduct of Military Partners’ (2017) 56 Military Law and Law of War Review 57, 61.

- 112ARIO commentaries, Article 14, para 6.

- 113ARIO commentaries, Article 15, para 4.

- 114ARIO commentaries, Article 16, para 4; ARS commentaries, Article 18, paras 2–4.

- 115Circumvention may thus overlap with direction and control, at least partially. See ARIO commentaries, Article 15, para 5.

- 116ECtHR, Bosphorus Airways v Ireland [GC], no 45036/98 (2005).

- 117See Article 8 Council Regulation (EEC) 990/93 concerning trade between the European Economic Community and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) [1993] OJ L102/14.

- 118TEU, Article 13.

- 119On the notion of ‘piercing the veil’ in international law, see eg Ahlborn (n 7) 46.

- 120See eg: UK House of Lords, JH Rayner (Mincing Lane) Ltd v Department of Trade and Industry (International Tin Council Case) [1989] 3 WLR 969, ILDC 1733 (UK 1990); ECtHR, Connolly v 15 Member States of the European Union (dec.), no. 73274/01 (2008); ECtHR, Boivin v 34 Member States of the Council of Europe (dec.), no. 73250/01 (2008); ECtHR, Andreasen v UK and 26 other member States of the European Union (dec.), no 28827/11 (2015).

- 121The intense focus on (dual) attribution in the literature may thus be an example of academic herd behaviour; see Rob van Gestel and Hans-Wolfgang Micklitz, ‘Why Methods Matter in European Legal Scholarship’ (2014) 20 European Law Journal 292, 305–307 <https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12049>.

- 122Helmut Philipp Aust, Complicity and the Law of State Responsibility (CUP 2011) <https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511862632>; Vladyslav Lanovoy, Complicity and Its Limits in the Law of International Responsibility (Hart 2016) <https://doi.org/10.5040/9781782259398>. Some articles have also appeared recently: Fry (n 27); Boutin (n 111).

- 123See eg Stian Øby Johansen, ‘Joint and several responsibility of the EU and its member states towards third parties’ (conference paper for the meeting of the Interest Group on the EU as a Global Actor, ESIL Annual Conference in Athens 2019 – on file with author).