Norway’s Constitution in a Comparative Perspective

Malcolm Langford

Director, Center for Experiential Legal Learning (CELL), University of Oslo

malcolm.langford@jus.uio.noBeate Kathrine Berge

Student Leader, Center for Experiential Legal Learning (CELL), University of Oslo

b.k.berge@student.jus.uio.noPublisert 20.12.2019, Oslo Law Review 2019/3, Årgang 6, side 198-228

The Norwegian constitution is the second oldest living constitution in the world, and the country’s Supreme Court was also the second in the world to judicially review legislation. Yet, Norway’s deep constitutional history has gone often unnoticed in comparative scholarship, while comparative constitutional law within Norway has not attracted significant attention, despite the many constitutional influences from abroad. This article introduces the Norwegian constitution to an international audience and places it within a comparative perspective for a Norwegian readership. After a brief overview of comparative method(s), the remainder of the article focuses on three core areas of constitutional law: system of government, judicial review, and constitutional amendments. Using descriptive statistics, qualitative case studies, and legal and archival sources, the Norwegian experience is situated within a global context.

Keywords

- constitutions

- judicial review

- constitutional amendments

1. Introduction

The Norwegian constitution of 1814 is one of the oldest constitutions still in force in the world, second only to the constitution of the United States. Moreover, in 1822, the country’s Supreme Court became the second national court in the world to constitutionally review legislation. Remarkably, however, Norway’s deep constitutional history and its influence on constitution making in the early-to-mid 19th Century has gone largely unnoticed in comparative scholarship. In the 1348-page Oxford Handbook on Comparative Constitutional Law, the Norwegian constitution is mentioned only in passing and Norwegian constitutional jurisprudence is rarely the subject of comparative analysis outside of Norway. This neglect is partly due to the Anglo-American dominance of comparative constitutional law, but it is also a result of linguistic barriers, Norway’s geopolitical (in)significance, and a Scandinavian Legal Realist tradition that played down the relevance of constitutional law to politics, policy and statutory interpretation. Yet, while the Norwegian constitution is unique in certain aspects, it is also the product of comparative influences. The original text was inspired partly by foreign law and the constitution is regularly amended.

The aim of this article is therefore in part to introduce the Norwegian constitution to an international audience. However, we are equally concerned with placing the constitution in a comparative perspective for a Norwegian readership. This is important for several reasons. From a so-called internal or legal perspective, comparative law may constitute an instrumentally relevant source in domestic law and policy arguments. It can assist interpretations of constitutional provisions, shape constitutional reform proposals (as occurred in a major revision in 2014), and inflect analyses of the constitutionality of legislative proposals. Some scholars argue that Norwegian Supreme Court judges have long read comparative constitutional law, although without necessarily citing it. Furthermore, comparative law formed an important part of early constitutional law scholarship in Norway, and has witnessed a revival in recent times.

Comparative constitutional law can also be useful for generating an external perspective, whether interdisciplinary or pedagogical, on the Norwegian constitution. By comparing the constitution to others, we can better appreciate how it functions in practice and relates to various social science theories. For example, by comparing free expression cases across countries, we can learn whether the Norwegian Supreme Court deviates from others in finding hate speech unconstitutional or affirming disadvantaged groups’ rights to speech. Moreover, comparative law can help us better understand our own system of law. It holds up a mirror that alerts us to constitutional features that may be surprisingly similar or different to other countries. A notable example was the attempted secession of Catalonia from Spain. Norwegian media criticised the Spanish constitution for failing to provide for a right to secede, but scholars responded by noting that precisely the same restrictions were incorporated in the Norwegian constitution. In other words, an engagement with a foreign constitution provided a lesson on the local one.

This article therefore seeks to introduce some key aspects of the Norwegian constitution in a comparative perspective. After a brief overview of comparative method(s) (section 2), the remainder of the article focuses on three core areas of constitutional law: system of government (section 3), judicial review (section 4), and constitutional amendments (section 5). In each of these substantive sections, we sketch the relevant theoretical categories, describe empirically the comparative landscape, and discuss the place of the Norwegian experience. The paper concludes in section 6.

2. Comparative law and method

2.1 Definitions

Before comparing the Norwegian constitution with others, it is useful to say some brief words about comparative method. First, it is important to define what we mean by comparative constitutional law. A strict and simple definition is that it constitutes the study of the similarities and differences between constitutional law in different countries and jurisdictions. Some include the mere description of foreign law and systems, but this dimension has increasingly fallen out of favour, as there is no ‘comparison’ taking place. Moreover, this one-way approach makes the physical location of the author and/or audience central to the definition, constituting a geographic nationalism that seems antiquated in an age of global communication and movement.

2.2 Presumptions: families, functionalism and contextualism

Second, there are different presumptions as to whether one will discover similarity or difference in the laws of different jurisdictions. A classical approach is to imagine that there are legal families and that similarity can be found within these groupings, but not between. This long tradition divides systems according to various (often Eurocentric) taxonomies. These include simple binaries (eg common law versus civil law), substantive traditions (French, German, English, Russian, Islamic, Hindu), dominant ideology (Western, Soviet, Muslim, Hindu, Chinese, Jewish), and historical fusions (Roman, Germanic, Common law, Nordic, Far East, Religious). Following this logic, we might expect the Norwegian constitution to have more in common with the Swedish constitution than the Spanish; or that European constitutions are more similar to each other than to East Asian constitutions.

In practice, the ontologicalism of legal families has met many challenges. While the influences of European and American legal systems on the Norwegian constitution fit with this approach, there are cases where similarities and influences are apparent across these groupings. For example, East Asian constitutions and constitutionalism have been heavily and directly influenced by Germany (beginning in the 19th century) and the USA (in the 20th century). Nonetheless, these categories may provide a starting point for inquiry, and new data-driven approaches may identify more clearly the transnational influences. For example, using computational topic modelling techniques, David Law finds four dominant ‘constitutional dialects’ across all constitutional texts during the last two centuries

An alternative approach is functionalism. Here, the presumption is that seemingly different legal systems will be largely similar in practice because each has the function of solving shared problems. As Tushnet writes: ‘Comparative constitutional study can help identify those functions and show how different constitutional provisions serve the same function in different constitutional system’. Thus, for example, given that legislatures and courts in Germany, France and the United Kingdom all need to balance the rights to free speech and privacy, it is presumed that each nation will arrive at similar solutions, even if the form differs. To be sure, functionalism does not presume that all solutions are equally worthy. Part of its motivation is to identify better solutions. By learning about how relevant rules function ‘elsewhere’, we may also ‘improve the way in which that function is performed here’. Nonetheless, given the similarity of the problem, it is presumed that solutions will not be too far from each other.

At the other end of the spectrum, we find the competing approach of contextualism. The presumption is that every legal system is complex and shaped by multiple historical, political and societal influences. This makes similarities difficult to identify, even within legal families. As Hegel writes, a constitution is ‘the work of centuries’ with a ‘consciousness’ developed for each particular nation. The contextualist claim is less directed at the written text of a constitution, formal or ‘large C’ constitutional law, which may be very similar among certain countries, particularly in light of the ‘cut-and-paste’ practice over the centuries. Instead, it is more focused on the material constitutional law of jurisprudence and other constitutional practice (‘small c’ constitutional law), which will be highly specific and unique. Like most countries, key aspects of Norwegian constitutional law can only be found in custom or judgments. In the United Kingdom, the entirety of constitutional law is found in practice – assorted legislative and quasi-constitutional documents and centuries of custom. However, whether the custom is formally or legally binding, or simply an accepted political practice, may vary.

This diversity makes comparative analysis for any instrumental or internal purpose challenging. As Montesquieu famously observed: ‘the political and civil laws of each nation … should be so appropriate to the people for whom they are made that it is very unlikely that the laws of one nation can suit another’. Thus, the role of comparative constitutional law, if anything, is to help us better understand our own system, by holding the wildly different foreign systems up as a reflection.

The debate on the merits of each perspective continues and, in our view, all deserve a hearing. In sifting through similarities and differences in the constitutional law of multiple jurisdictions, legal families may provide some initial indications, functionalism directs us toward comparable objects and possible solutions, and contextualism reminds us of vast cultural differences. Ultimately, comparative law is an art rather than a science, providing heuristics rather than neat answers; as well as a tool to understand constitutional transplants – where countries borrow law from each other – and the circulation of ideas.

2.3 Methodology

This leads naturally to asking, what is the methodology of comparative law? Much can be said, but only a few short points will be made. The first is that caution should be taken in merely comparing the formal texts of constitutions or other laws in the pursuit of answering questions concerning the legal position on a particular issue. As Sacco famously stated: ‘It is wrong to believe the first step towards comparison is to identify the legal rule of the countries to be compared … we must speak instead of the rules of constitutions, legislatures, courts, and, indeed, of the scholars who formulate legal doctrine’. This conglomeration of sources relevant to a legal question is what Sacco labelled ‘legal formants’.

A good example of applying legal formants can be found in Sejersted’s analysis of the five Nordic constitutions. He begins by observing that the five texts differ profoundly on almost every measure – length, age, structure, presence of judicial review, form of constitutional amendment, etc. The Norwegian constitution is described as ‘an old castle’, while the Finnish is likened to a ‘stylish modern opera house’. Yet, in terms of constitutional practice, the actual differences are less pronounced. There are also similarities in the use of constitutional custom, the practice of judicial deferentialism, and constitutional convergence through Europeanisation. Thus, care should be taken in mistaking constitutional form for substance.

A second methodological point concerns the choice of jurisdictions. Whether explicit or not, a theory almost always guides the choice of jurisdiction. The question is whether the theory is defensible. Thus, if the point of comparison is to generalise, for example by claiming that ‘many’ jurisdictions adopt such-and-such legal doctrine, or that ‘all’ parliamentary systems have such-and-such characteristics, a few cases or vague references will not suffice. One can be quickly accused of cherry-picking. Justice Scalia famously, though perhaps unfairly, accused his colleagues on the US Supreme Court of competing for the ‘Prize for the Court’s Most Feeble Effort to fabricate’ a consensus across nations. Yet, if the point is simply to say that a certain legal approach is possible, referring to a single jurisdiction may suffice.

A safer approach is to draw on social science case selection methods, which provide a more rigorous framework. By way of illustration, if the point is to analyse the interpretation or effectiveness of a certain legal approach for a country, choosing similar countries (a ‘similar systems design’) may help identify whether the rule works. Alternatively, if the aim is to export a legal solution, a ‘different systems design’ may be useful. It may be important to learn whether the rule works in different types of countries.

3. System of government

3.1 Key distinctions

Moving beyond methodology, we now turn to the first object of comparison in constitutional law: the system of government. Three important dimensions are discussed: presidentialism versus parliamentarism; negative versus positive parliamentarism; and unicameralism versus bicameralism.

3.2 Presidential versus parliamentary systems

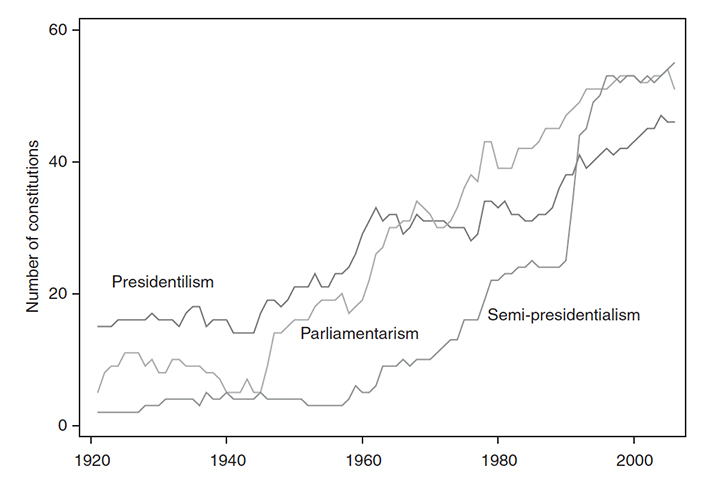

The most classical division in constitutional law is between three forms of government (presidential, semi-presidential and parliamentary). The standard and stylised account is that in presidential systems, the head of state and the head of legislature are separately elected, chosen or constituted. Influenced by the US model, it is presumed that the legislature controls the legislative agenda and its own dissolution, while a powerful head of state – the president – has the power to appoint and remove members of cabinet, veto legislation, and enjoy a wider array of emergency powers. In a parliamentary system, the executive requires the confidence of the legislature, but enjoys executive decree powers in discrete areas. The formal head of state may be a monarch (eg, Norway) or an elected head of state (eg, Finland), but their powers are either symbolic or minimal. A semi-presidential system blends aspects of both. The most well-known is the French system. The head of state and legislature are separately elected, but the government is formed jointly and is answerable to parliament. Figure 1 shows that the distribution of the three systems of government is now relatively even across the world, after presidentialism dominated in the lead-up to the Second World War.

Figure 1

The three systems of government over time: 1920–201030. Extracted from José Antonio Cheibub, Zachary Elkins & Tom Ginsburg, ‘Beyond Presidentialism and Parliamentarism’ (2014) 44(3) British Journal of Political Science 515.

The advantages and disadvantages of both systems have been long debated. Proponents of presidentialism argue that it provides more legitimacy to the executive (when directly elected), enhances stability (presidents are not subject to votes of no-confidence), ensures clear separation of powers, and enables the executive to act more decisively and quickly. Parliamentary proponents counter that presidentialism increases the likelihood of a slide to authoritarianism, boosts the chances of legislative and policy gridlock as different branches of government exercise veto powers, makes it more difficult to remove unpopular leaders, and reduces the pressure to build consensus (which is often the only way to form a government in parliamentary systems with proportional voting).

Regardless of the virtues of both models, the accuracy of their labelling has been strongly criticised. Firstly, the trichotomy of presidential, semi-presidential and parliamentary does not do justice to the significant and important variations within each type of system. For example, parliamentary systems vary widely in their design. Some parliaments are unicameral, while others include an upper house, such as the Bundesrat in Germany or the Senate in Australia. Some systems embrace ‘positive parliamentarism’, requiring the government to obtain the declared support of the parliament; while others have ‘negative parliamentarism’, in which a government can continue to rule until it suffers a loss in a vote of no-confidence. Yet others, like Germany, have a system of constructive parliamentarism, in which a vote of no confidence cannot happen unless a new head of government is elected at the same time. Other features of parliamentarism also vary widely, such as the ability of the executive to issue executive orders. One practical implication of this is that a government in a parliamentary system can enjoy significant power if the system is based on negative parliamentarism, there is a wide discretion to issue executive orders, or the government holds the majority in a unicameral legislature – as is the case in Norway at the time of writing.

Secondly, there is significant variation across the three types of systems. Indeed, some scholars question whether the trichotomy has any significant classificatory meaning. Using statistical regression analysis, Chibub, Elkins and Ginsburg found that there was only a weak correlation between countries’ formal system of government (presidential, semi-presidential, and parliamentary) and the actual powers given to the legislature and executive. Many presidential systems resemble parliamentary systems in relation to the allocation of powers, and vice-versa. For example, in some presidential systems, the president does not control the appointment of cabinet; while in some parliamentary systems, executives possess many emergency-like powers. The authors of the study found instead that the best predictor of the actual division of powers is time and place of the writing of the constitution – together with a country’s type of legal system. Constitutions written at the same time, or within the same region or legal tradition, were more likely to exhibit similarity. Whether they were presidential or parliamentary is less relevant. Thus, constitutional powers tend to be creatures of context rather than abstract design; and they change over time, whether formally in written text or through constitutional practice.

The division of powers within the Norwegian Constitution provides a pertinent illustration of the importance of context. In 1814, in a brief intermezzo of geopolitics, Norway embarked on the frenetic drafting of a constitution. While Sweden had formally gained Norway from Denmark under the January 1814 Treaty of Kiel due to Denmark’s support for the Napoleonic forces, Norwegians contested this transfer of sovereignty as against natural law. Claiming instead that sovereignty reverted to Norway after the dissolution of the union with Denmark, and partly inspired by Rousseau’s widely read The Social Contract and the American experience, an alliance of Norwegian elites, free peasants and the resident Crown Prince of Denmark sought to thwart the transfer.

On 16 May 1814, after just six weeks of negotiations at Eidsvoll, a constitutive assembly of elected representatives adopted the Norwegian Constitution, which, with a selection of individual rights and elected parliament, was markedly liberal for the time. The Danish prince Christian Fredrik was elected as King of Norway the following day. Independence was short-lived, as Swedish troops overpowered the undermanned Norwegian forces a few months later, but the Norwegian constitutional efforts allowed Norway to enter into a union with Sweden on a more equal footing. The newly minted constitution survived, as well as the governing system it created, though with the Swedish King as head of state.

As Article 1 of the Norwegian constitution still provides, Norway became a ‘limited’ or constitutional monarchy, as opposed to a part of an absolute monarchy as it had been under Denmark. However, the constitutive assembly rejected the idea of parliamentarism, and the executive was originally fully independent of parliament. So even though the assembly might have been inspired by Montesquieu’s The Spirit of Laws and his call for three separately institutionalised bodies of power – executive, legislature and the courts – that would check each other, the approach in the Norwegian constitution was somewhat distinct, although keeping with the European trend of the time. As Holmøyvik and Michalsen point out, while Montesquieu’s theory of balanced powers made only a partial imprint on the text, notions of popular sovereignty were still deeply embedded in the structure. The parliament was given significant drafting and approval powers over legislation, and despite Montesquieu’s argument that the King should have absolute veto, the Norwegian constitution only allowed the King a suspensive veto-power over ordinary legislation.

Nonetheless, the legislature was given few opportunities to exercise control over the executive. The government was not required to possess majority support in the parliament; and only one member of the constitutive assembly at Eidsvoll, Judge Wulfsberg from Moss, proposed and voted for the motion that the cabinet be elected by the parliament rather than the King. Members of the cabinet could be appointed from outside the parliament and, once part of cabinet, could not attend parliament. This shielded them from parliamentary debate and criticism. While cabinet members could be ‘impeached’ by parliament, the pro-independence party at Eidsvoll blocked a series of concrete proposals that would have made the executive more strongly accountable to the parliament.

Over time, Norway moved gradually, but not completely, towards a more archetypal British model of parliamentarism. During the 19th century, the separation of powers became both the backdrop and the tool of a power struggle between the parliament and the crown, and manifested in the broader struggle for popular influence and expansion of voting rights. The King could delay legislative bills through suspensive veto, but it was the parliament that decided taxation and the state budget. Frustrated by the absence of majoritarianism (majority rule in the parliament), the parliament began to challenge the King’s powers. In 1884, after the King vetoed constitutional amendments that granted the members of the cabinet the right to attend parliament, the parliament impeached the cabinet, stripping them of office for refusing to implement a parliamentary resolution. The crux of the matter was that the parliament did not recognise that the King had veto-power in constitutional affairs. The conflict resulted in the opposition leader, Johan Sverdrup, forming the first government consisting of members of the elected parliament, which also had the support of the majority in parliament.

However, it took time for parliamentarism to become embedded both in practice and in constitutional law. Sverdrup’s first government quickly lost the support of the majority without considering this as a reason to resign; and the government of Emil Stang refused to step down, despite two votes of no confidence in 1893 and 1894 respectively. It is not clear when it became a legal duty for Ministers to step down after a vote of no confidence, but the rule was formally enshrined in the constitution in 2007. Moreover, there are many features of Norwegian parliamentarism that remain distinct from the British model. In Norway, Cabinet members need not be members of parliament, and executive reserve powers are arguably greater in Norway. The British High Court of Justice has recently underlined the existence of strong parliamentary powers, both regarding control over all executive acts affecting legislated rights in its renowned Brexit decision and the exercise of prerogative powers that affect the efficacy of parliament.

3.3 Negative versus positive parliamentarism

This peripatetic journey towards majoritarianism may explain why negative rather than positive parliamentarism evolved in Norway. In Western Europe, the latter is the dominant model. Nineteen countries, from the UK to Finland, require that the government must have the support of the parliament, commonly through an investiture vote, to be able to form. Six countries have negative parliamentarism: Norway, Iceland, Denmark, France, Austria and the Netherlands. In these countries, a government must only be tolerated by the parliament; its formation does not require an active endorsement or vote of confidence.

Portugal and Sweden represent a middle category. A formal positive investiture vote is required, but the systems’ substantive characteristics are fully negative. In Portugal, the executive presents itself and its legislative programme to the parliament ten days after formation and must ensure that a majority does not vote against itself and the agenda. In Sweden, a government must simply ensure that half the parliament does not vote against its formation. The investiture vote in Sweden in 1978 represents the extreme example. In 1978, Ola Ullsten from the Liberal’s People Party became prime minister with the support of only 39 out of the 349 members. This was because only 66 MPs voted against Ullsten and 215 abstained. The defeat of the nomination required 175 votes against.

The literature is divided on why countries choose positive or negative parliamentarism. Some scholars argue that the negative form is adopted in countries in which parliament have sufficient ex post control over the government. Thus, there is little danger in permitting a minority government to continue, as the parliament still holds many of the strings. On the contrary, the positive form is said to be adopted when there is greater ‘agency loss’. Governments are less accountable to parliaments and the investiture vote represents an important form of parliamentary supervision.

This ‘neo-institutionalist’ explanation has been challenged statistically and historically. Russo and Verzichelli argue that there is no strong correlation between the forms of parliamentary powers and negative/positive parliamentarism and claim, instead, that the choice is influenced by context. One important factor is the ability to form a stable government. In Italy, the authors claim that positive parliamentarism was selected in order to ‘disincentivise’ parties from withdrawing their confidence for ‘futile reasons’. Thus, an investiture vote, in theory, enabled a government to survive. In Portugal, however, the concern was different: establishing a government in the midst of political fragmentation. Negative parliamentarism offered a solution. Significant time and energy were no longer needed to find a majority, and governments could be easily formed.

The Norwegian experience provides some support to the contextual explanation. Indeed, it is comparable to the Portuguese experience in terms of some of the reasons given for negative parliamentarism. Up until 1908, none of the three parties of the Norwegian parliament had the support of the majority. This made the principle of majoritarianism from 1884 difficult to operationalise. The solution was negative parliamentarism. The government could form relatively quickly without needing to obtain the active support for a legislative programme from a majority in parliament. The result has permitted many ‘minority’ governments to form and rule for extended periods. A classic example is the formation of the Bondevik I coalition government in Norway in 1997. While the governing parties possessed only 26 percent of the seats in parliament, and the Labour party held almost 40 percent, the latter declined to bring a vote of no-confidence. Political scientists have speculated that with a rule of positive parliamentarism, active support from the Labour party would have been highly unlikely.

Thus, the negative model more easily permits so-called minority parliamentarism. Governments may not hold the majority in parliament, but maintains its implicit support to govern. However, minority parliamentarism can lead to weak governance, as the government possesses limited powers to push contentious matters through parliament. In a functionalist vein, we can observe therefore that countries with negative parliamentarism use different constitutional mechanisms to guard against the overuse of no-confidence votes or the blocking of important legislation. In Norway, one such measure is the ‘cabinet question’. A minority government can threaten to step down if the parliament does not vote in its favour. If the opposition is unsure as to whether or not they can form an alternative government, they may defer to the executive. This is what eventually led to the downfall of the Bondevik I coalition: the Prime Minister posed a cabinet question concerning maintaining pollution legislation that would have prevented a new gas plant, stating that the government would step down if the parliament voted against its proposal – which is what transpired.

Similarly, but differently, in Portugal, the executive is provided formal constitutional protection. In Article 194(3), the Portuguese constitution provides that if a motion of no confidence is unsuccessful, its signatories may not make another such motion during the same legislative session. This may explain, for example, why the right-wing opposition in 2019 waited until almost the end of the current electoral period to test the parliamentary confidence in the left-wing government. With only one shot, the no-confidence vote was brought when the opposition most wanted to signal their disagreement with the government’s legislative agenda.

3.4 Unicameral versus bicameral models

Finally, a word should be said about unicameral and bicameral models. In 1999, the Inter-Parliamentary Union found that 38 percent of parliaments had upper chambers. Thus, the unicameral system is (only just) the norm. Unicameral systems are typically found in small countries with a unitary system of government, such as New Zealand and Luxembourg. However, there is a tendency towards new upper houses, such as were recently created in Algeria, Liberia, Morocco, Nigeria, Senegal and Slovenia. It may represent a somewhat recent trend to protect minority, sectoral and sectarian interests through structural representation, and not simply judicial review.

What is particular about upper houses is their remarkable diversity. They differ in size (the Belize senate has eight senators; the British House of Lords has had up to 1,325), selection (elected vs. appointed), representative model (groups, geography or other factor), role (delay, advisory, legislative), powers (veto power, subordinate) and policy space (areas, numbers of committees). In this kaleidoscope of models, the USA and UK again provide bookends.

In the United Kingdom, appointment to the House of Lords is based on historical tradition and some form of group affiliation. The chamber has historically been strongly dominated by the clergy, hereditary aristocrats and judges. Recent reforms removed judges, drastically curtailed the number of hereditary peers, and favoured appointments on recommendations to the Queen based on proposals from political parties (which could also be seen as a group). Moreover, the effective powers of the House of Lords have been reduced over time. Today, the House of Lords has three main roles: it shares the task of drafting laws with the House of Commons, conducts in-depth consideration of public policy and holds the executive to account through careful scrutiny of the work of the government.

In the USA, however, appointment is based on some form of geography: two senators are appointed from each of the fifty states. This balances smaller states’ comparative lack of representation in Congress, which is (largely) based on population size. The Senate is also extremely powerful: it has the power to impeach government officials (which has been done 17 times since 1789), approve or reject treaties and presidential appointments to executive and judicial branch posts (including the powerful Supreme Court), delay or block legislation through filibustering, and investigate malfeasance.

In Norway, a partial form of bicameralism was initially introduced in 1814. A quarter of elected parliamentarians were to sit as an upper house (Lagtinget). The lower house (Odelstinget) consisted of three quarters of the members of parliament. This was a functional division of the same group of representatives, as opposed to the institutionally separate division between the House of Lords and the House of Commons in the UK. Apart from members of the cabinet, only those sitting in the lower house had the right to submit a bill for consideration. Any bill submitted to parliament was first considered and put to the vote there, before it went through to the upper house. If the bill was not passed by Lagtinget, it was sent back to Odelstinget and subsequently resubmitted to Lagtinget. If not passed by the upper house the second time, the bill was put to the vote in Stortinget, with parliament acting as one chamber. The bill would pass if it was backed by a supermajority (two thirds).

The design of the two chambers of the Norwegian parliament, with an upper house that has been referred to as ‘pseudo-upper house’, was very much intentional. The division of the National Assembly into two chambers was based on the desire to secure careful deliberation of legislation; the weakening of the upper house, as compared to the United Kingdom and the United States, was in part due to avoid the possibility of deadlocks between the two chambers halting the legislative process, as well as the social structure in Norway. Interestingly, the Norwegian bicameral model resembled the legislature of Iceland, where the National Assembly (Alþingi) was divided into two chambers (efri and neðri deild) until 1991.

However, in 2009 Norway officially adopted the unicameral model, as the division between the houses had lost all significance. While there is often a different power balance in the different houses of a traditional bicameral system, the division of the Norwegian parliament was done in such a way that the power balance in both houses reflected the power balance in parliament. Like the other Nordic countries, Norway has several committees, each dedicated to their own field, that prepare issues for plenary sessions – and here, too, the parties are proportionally represented. A practical consequence of this was that the political battles where already fought by the time a bill reached Lagtinget: first in the committees, and then in Odelstinget, with the result that Lagtinget lost all practical influence. If a committee member had a seat in Lagtinget, they were effectively excluded from participating in plenary debates where they would possess a high degree of knowledge of and interest in the matter at hand, as meetings in the upper house were held without any kind of debate or vote. To replace the dual debate the houses were intended to generate regarding legislation, the constitution was changed so that at least two deliberations three days apart are required for a bill to become law, and the bill has to be passed twice.

As it is today, the Norwegian system is similar to the powerful unicameral systems of New Zealand and Luxembourg, as well as the neighbouring Swedish Riksdagen, the Danish Folketinget, the Icelandic Alþingi and the Finnish Suomen eduskunta, also known as Finlands riksdag. In all five Nordic countries, the number of members of parliament is quite large compared to population size. In Norway, Sweden and Finland, this is partly because the rather small populations are scattered over relatively large geographical areas, resulting in a high number of seats to ensure fair representation of the different parts of the countries.

4. Judicial review of legislation

4.1 Different forms of judicial review

We move now to the third branch of government – the courts – and focus on their powers to review the constitutionality of legislation. Globally, the prevailing models of judicial review draw mostly on the early American and Austrian models. In 1803, the US Supreme Court asserted its power to interpret constitutional rights and invalidate legislative and executive action as an incident of the judicial role in adjudicating concrete cases. The competing variant, the ‘Kelsenian’ Austrian Constitutional Court of 1920, involved the creation of a discrete and specialised judicial body – a constitutional court – for these purposes. The Austrian court possessed the sole power to consider the constitutionality of legislation after it had become law, in both concrete cases and abstract review proceedings. The Austrian model found acceptance mostly through the fame gained by the powerful German Federal Constitutional Court, a post-Kelsenian prototype. Indeed, globally in the post-cold War era, the ‘most common constitutional configuration is a combination of a French-style mixed governmental system [see section 3 above] with a German-style constitutional court’.

The genealogy and evolution of courts is nonetheless untidy. Like systems of government, their institutional and jurisdictional features can vary radically within and between binary categories. We examine five different features of judicial review – when it can be exercised, who can invoke it, where it can be adjudicated, what issues can be addressed, and how judicial review is practised – and then put the Norwegian experience into a comparative and historical perspective.

In parsing below the adoption of these different forms of judicial review, it is important to note that the long-standing debate over judicial review has influenced some if not many of the constitutional design principles. Proponents of judicial review point to the important role of courts in providing legally solid interpretation, an independent and impartial arena, a forum for accountability, and possibly a democratic space that permits deliberation, participation and representation by groups with little or no electoral influence. Yet, critics of judicial review contest each of these points. They point to the weakness of legal method in adjudicating vague constitutional provisions, political biases of judges, courts’ lack of democratic legitimacy and institutional competence on specialised questions, and the ineffectiveness of courts in enforcing their orders. Thus, while the evolution of judicial review in each country is influenced by its own conditions and historical happenstance, these debates can be found in virtually every country and inflect often the architecture and application of judicial review.

Turning to the different design features, first, there is a question of when judicial review occurs. It can be exercised ex ante (before the law has been enacted) or ex post (after the law has come into effect). When judicial review takes place ex ante, it can be compared to an advisory opinion regarding the legislation at hand, except that the result is a binding judgement. Its advantage is that it promotes judicial efficacy, as early interference prevents unconstitutional acts from becoming problematic law that has to be dealt with later. In France, Article 61 of the constitution provides that the Conseil constitutionnel must review legislation that affects the powers of key institutions, parliamentary rules of procedure and any legislation that is referred to the court for review by the President, Prime Minister, the lower or upper house, or sixty members of one of the houses. However, it must deliver its ruling within one month, or within eight days in cases of urgency. Due to this time frame, and the challenges that lie in predicting the effects of legislation, ex ante review may be less scrutinous than ex post review. Nonetheless, it is exercised, and with effect. For example, France amended its constitution to make room for gender-based affirmative action. But in 1982, the Conseil held that affirmative action quotas for women violated the constitutional right to equality, leading to a new constitutional amendment in 1999. A new law requiring overall gender parity in certain party election candidate lists was then reviewed in 2000, which was found constitutional by the Conseil, with some minor exceptions.

Judicial review ex post takes place when the courts review the legality of an act or measure after it has come into effect. While courts are ordinarily bound by the laws they would need to assess, several countries have provided the courts with the authority to review the constitutionality of legislation by creating a separate constitutional court (Kelsenian model) and/or creating a hierarchical system of legal acts, with the constitution being of superior rank (the American model). The advantage of ex post review is that it interferes less with parliamentary and executive freedoms, and is often only focused on concrete problems.

However, an increasing number of countries embrace both forms. For example, in France, a 2008 reform permitted two supreme courts (and indirectly lower courts) in concrete cases to refer constitutional questions to the Conseil constitutionnel. In the first two-and-a-half years of the procedure’s operation, there were 261 cases referred, with unconstitutionality declared fully or partly in 26 percent of cases. And, in the renowned 1994 South African constitution, an entire spectrum of review is set out in section 167. This includes standard ex post review of concrete disputes, ex ante review if the President is unsure of the constitutionality of a bill (section 79), and a middle category in which members of the national parliament (at least a third) can challenge a law’s constitutionality within 30 days of it receiving assent by the President (section 80).

Secondly, there is a question of who can seek relief. There is great diversity in the rules of standing (who can make a claim and whether they need to be a victim). Due to the invasiveness of ex ante judicial review into the domain of the legislature, there is typically a very narrow group of people who can refer draft legislation to the courts for this type of review – as in the French system, where it is limited to members of the government or parliament. In other words, standing is limited to those with legislative powers or who will be required to implement the law. However, in the American model of ex post review, courts commonly require that the litigant has a concrete or material interest, as a victim. This means that the executive or legislature must also demonstrate an interest if they wish to pursue a challenge. For example, when the State of Hawaii challenged President Trump’s so-called Muslim ban on immigration, they grounded their standing on the basis that tourism revenues and travel of foreign students to State universities would be adversely affected.

However, standing rights have steadily increased in constitutions across the world in relation to ex post review. This covers abstract review, where small numbers of parliamentarians, non-governmental organisations and publicly minded citizens (‘actio popularis’) can challenge laws in the abstract. For example, in Germany, if the parliamentary opposition wishes to stop the implementation of important acts put forth by the government, it will challenge the legislation before the Federal Constitutional Court. The Hungarian experience in the 1990s is perhaps the most prominent example of expanded standing for abstract review with the former Chief Justice noting that ‘actio popularis became a substitute for direct democracy’. Enhanced standing rights extend also to concrete review, whereby constitutions or judicial practice can enable a very wide definition of a material interest in a case. Even in the United States, where standing rules concerning material interest or ‘particularised injury’ are very strict, it is possible for organisations to challenge legislation for its constitutionality if some of their members could have done so in their own capacity or there is direct injury to the organisation, which can include diversion of resources and/or frustration of mission.

Thirdly, there is a question of where relief can be sought. Here, the two general models provide some substantive guidance. In the Kelsenian model, all constitutional matters are usually heard in a centralised manner by the constitutional court. On the other hand, in the decentralised model, as in the USA, judicial review powers are diffused and lower courts may also hear and determine constitutional matters. However, there are always exceptions. In Portugal, ordinary courts can set aside statutes on the grounds that they are constitutionally invalid, with the possibility of appeal to the Constitutional Court.

Fourthly, there is the question of what can be adjudicated. In many jurisdictions, courts are actively involved in regulating the powers of branches or units of government. This includes regulation of conflicts between the executive and the legislature. For example, the German Federal Constitutional Court has ruled on whether the parliament can participate in all deployment decisions concerning the Germany military or control the budget of the intelligence services. Likewise, the UK Supreme Court recently found the executive’s prorogation of parliament to be unlawful. In federal states, courts must often resolve disputes between states and the national government. In many of these cases, the courts must take a position, which results in them being quite active and/or powerful.

However, most courts are reluctant to intervene in intra-branch conflicts such as parliamentary rules of procedure. The most famous and influential articulation of this approach can be found in Article 9 of the English Bill of Rights, which enshrined a 15th-century customary rule: ‘That the freedom of speech and debates or proceedings in Parliament ought not to be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Parliament.’ However, this practice is changing in some countries. For example, the majority of the South African Constitutional Court in Mazibuko v Sisulu found that there was an unconstitutional ‘lacuna’ in the National Assembly Rules regarding the scheduling of a debate and vote on a motion of no confidence in the President. Thus, a parliamentary member had a right to their motion being tabled in parliament even if it first had to be processed by a parliamentary committee.

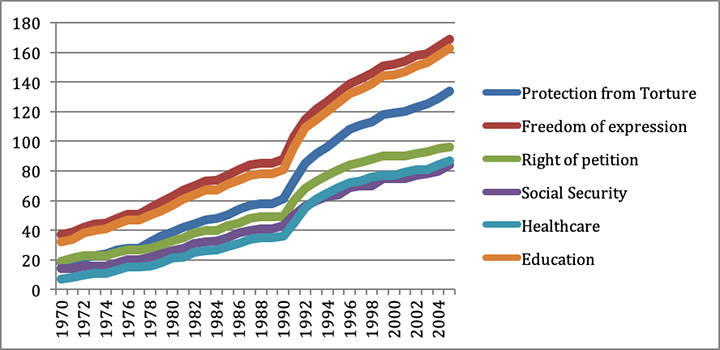

Individual and collective rights are, however, a common subject. Indeed, constitutional rights and international human rights treaties with constitutional status have captured significant attention in relation to judicial review. While the scope of recognised and reviewable rights and the nature of exceptions and limitations varies considerably, the general trend in both constitutional law and international law has been the expansion of review from a limited number of narrowly framed civil rights to a broader catalogue of rights and duties. Figure 2, for example, shows the dramatic rise in the constitutional recognition of a set of civil and social rights in constitutions, and concrete cases are discussed below.

Figure 2

The Constitutional Rights Revolution

Finally, there is a question of how a court reviews constitutionality. In terms of fact-finding, it often happens at the court of first instance, which can be a lower court or a constitutional court. Some courts launch investigations, or proactively call in third parties and amicus curiae. In terms of the strength and nature of judicial review, most courts develop their own approach within their ‘inherent jurisdiction’ as to whether constitutional provisions are justiciable, how the provisions should be interpreted, and how strictly they should be enforced. Some courts are deferential and cautious, while other engage in searching scrutiny of the constitutionality of legislation; and these doctrinal paradigms tend to shift over time in response to political pressures, developments in legal theory and social meanings, and changes in legal culture and judicial personalities. However, constitutions can sometimes provide guidance on these matters, with exceptions and qualifiers indicating the nature and strength of intended judicial review. There is also great variation in the types of remedial powers accorded to and used by courts. Some courts adopt the traditional and binary American model of simply declaring whether a law is constitutionally valid or not. Others are active (ordering and supervising follow-up remedies and even writing interim legislation), while yet others are reflexive and use remedies to coax state organs to a consensus or optimal result (eg through declaration of validity or follow-up proceedings where governments propose a remedy that is reviewed for its reasonableness). In this respect, the German, Canadian, Portuguese, Colombian and Indian courts are interesting for the diversity of remedies they impose.

4.2 Early Norwegian judicial review in a comparative perspective

Inspired by the American and French declarations, the 1812 Spanish constitution, the writings of Kant, Rousseau, Voltaire and Adam Smith, and experiences with English liberalism, the Eidsvoll assembly included a set of core civil rights within the Norwegian constitution. These included habeas corpus, protection against torture, freedom of expression and the right to property. However, like its American cousin, the newly minted Norwegian constitution was ambiguous on the powers of judicial review. Yet, this did not halt the Norwegian Supreme Court in assigning to itself the power to invalidate legislation that contravened the constitution. A mere nineteen years after the US Supreme Court judgment in Marbury v Madison, the Norwegian Supreme Court first exercised, in practice, its power of judicial review: it found that the cancellation with retroactive effect of the rights of certain civil servants in Trondheim to auction copper violated constitutional rights on property expropriation and non-retroactivity. To avoid a formal conflict with parliament, the relevant constitutional provisions were read into the law.

This early breakthrough in 1822 and its successors were undoubtedly influenced by the American experience. However, after Marbury v Madison, the US Supreme Court did not invalidate legislation again until Dred Scott v Sanford in 1857, while the Norwegian Supreme Court continued invalidating laws in the 1840s and 1850s. Thus, scholars argue that the development of judicial review in Norway was equally a product of indigenous factors in Norwegian political and judicial development. Moreover, the Norwegian experience diverged from the American in two important respects. First, the Norwegian court initially only issued brief formal conclusions, although these were the subject of public and legal debate. Second, it avoided striking down legislation as much as possible, preferring to interpret the legislation in a way that made it constitutional – so-called ‘reading in’. It was only in 1866, in the Wedel Jarlsberg judgment, that the Chief Justice formally articulated the grounds and method for exercising judicial review – in text similar to that of Marbury v Madison – and struck down legislation.

Second, the Court’s willingness to exercise judicial review was not necessarily oriented towards limiting state power, and the Supreme Court often, but not always, aligned itself with parliamentary conservatives during the 19th century. The real test of judicial review came with the transition to social liberalism and then social democracy in the early 20th century, especially in relation to restrictions on the right to property. This question was the order of the day on the other side of the Atlantic and Norwegian judges were aware of the American judiciary’s attempt to hold back social reforms. Between 1885 and 1935, state and federal courts in the USA struck down ‘some 150 pieces of labour legislation’ on the grounds that they violated economic liberties in the constitution. In the Lochner case of 1905, the limitation of working hours for bakers (a maximum of ten a day, and 60 a week) was found to violate the ‘liberty of contract’, implicit in the due process clause. In 1923, the US Supreme Court invalidated minimum wage legislation on the basis that it interfered with liberty of contract as it amounted to a ‘compulsory exaction from the employer for the support of a partially indigent person.’ Only when President Roosevelt threatened to pack the courts with additional pro-Executive judges did a range of social legislation escape judicial sanction.

In Norway, there was also a deep division over whether Norwegian judicial review should serve as an instrument of the emerging social welfare state, or a firewall against it. This rupture came to a head in a major case concerning expropriation of hydro operations after the expiry of a concession. The relevant law was passed by a Venstre-led social liberal government, but drafted by the Minister of Justice, Castberg, a prominent lawyer from a more left-leaning party. It targeted particularly foreigners that were beginning to invest in Norwegian hydroelectric power. Castberg defended the law on a general basis: the right of all Norwegians to benefit. The matter ended in the Supreme Court eight years later, in the case Rt-1918-403. A narrow majority (probably due to some branch-stacking by the social liberals) found that the law did not amount to expropriation. While the general principle of judicial review was retained, the case was representative of a number in which the Norwegian Supreme Court, like its American counterpart, moved to a distinctively deferential model of judicial review in order to accommodate the rise of the welfare state – but interestingly, two decades earlier.

However, and also like the US Supreme Court, the Norwegian Supreme Court continued to view itself as the guardian of the constitution. Following the German occupation in 1940 and the prohibition of the judicial review of regime regulations, all the justices resigned their positions in a joint letter. They stated that it would ‘counter their professional oath not to review the constitutionality of laws and regulations’, and that in war-time, this would include reviewing the laws of the occupying power under international law.

4.3 Modern Norwegian judicial review in a comparative perspective

In the aftermath of the Second World War, judicial review emerged in a wider range of jurisdictions and with a stronger focus on a broader range of rights. Prominent courts included the Federal Constitutional Court of West Germany and the Italian Constitutional Court, while the US Supreme Court dramatically expanded its protection of civil rights in areas such as abortion, equal access to schooling for ethnic minorities, and protection of religious minorities.

The German apex court was particularly notable for its jurisprudential innovation and influence. This has included the proportionality doctrine, enforcement of a minimum essential level for socio-economic rights, and integration of the right to human dignity throughout its constitutional interpretation. For example, the Court underlined the principle of human dignity in striking down legislation permitting life imprisonment: ‘It would be inconsistent with human dignity perceived in this way if the State were to claim the right to forcefully strip a human of his freedom without [the human] having at least the possibility to ever regain freedom’. It also subsumed human dignity and the directive principle of the Sozialstaat in the 1960s to establish a right to an existenzminimum: the State must ensure ‘every needy person the material conditions that are indispensable for his or her physical existence and for a minimum participation in social, cultural and political life’. However, not all cases are successful. For example, a minority group of parliamentarians tried, but failed, to have legislation regarding genetically modified crops held unconstitutional. The Court has also diverged from the US Supreme Court significantly on some issues, for example finding that legislation decriminalising abortion was unconstitutional, in 1975 and 1993, as the respect for human dignity required the criminalisation of unjustified abortions.

As the Cold War drew to a close, the third wave of democracy and judicial review of legislation exploded across the world. The reason was partly legal – reformed constitutions provided stronger powers to courts – but it was primarily political. Individual rights had gained greater acceptance, there were growing demands for courts to restrain parliamentary and executive excesses, and courts found more room to manoeuvre with increasing political fragmentation and support from new international court and tribunals. The result was the development of public-interest litigation in South Asia in the 1980s, active Eastern European courts in the first post-communist decade in the 1990s, a Latin American judicial revolution from 2000, and the gradual but robust emergence, or re-emergence, of Western European, Asian and African courts in the last decade. The most innovative and active court of this period is undoubtedly the Colombian Constitutional Court. It has issued structural orders for the reform of the prison system and the services for 6 million internally displaced persons, recognised same-sex marriage and interpreted the right to immediate relief for violation of fundamental rights broadly, so that millions of individuals have been secured rights ranging from habeas corpus to access to HIV medicines. While some local factors such as armed conflict and political corruption provide one contextual reason for the rise of the court, the Court has produced a jurisprudence that is widely quoted in the region and beyond and has become itself a major object of global study by constitutional specialists – both legal and social scientific.

However, not all courts have followed this trend. In the Nordic region, for example, while Finnish courts have been willing to apply a broad range of rights following the constitutional reform of 2000, Swedish and Danish courts have been more cautious – though it should be mentioned that the Swedish constitutional reform of 2010 formally allowed a wider scope for judicial review of legislation, as there is no longer a requirement of a manifest violation. The Norwegian Supreme Court has trodden a middle road. In 1976, the Supreme Court signalled a return to a more robust form of judicial review of legislation, especially in cases concerning core civil rights, by a narrow majority in the Kløfta case. The Court moved slowly over the next few decades in enforcing this new approach, with scattered but landmark decisions on key issues. In the case of Rt-2010-143, the court repealed the government’s tax assessment of several shipping companies because the transitional regulations leading to a change in tax regulation was in violation of the constitutional prohibition against retroactive laws. While there remains a divide in the Court over its appropriate role, there is a significant openness to questions of rights. Moreover, in judicial review of administrative acts under the Human Rights Act, the Supreme Court has arguably been less deferential than in cases concerning constitutional review of legislation. For example, in the case of Rt-2015-93, the Court overturned the government’s decision to deport a rejected asylum seeker due to the rights and interests of her young daughter, who was a Norwegian citizen through birth.

The Court was partly pushed in this direction by the European Court of Human Rights. In 1952, in the first case against Norway, the complaint concerning military service objection was dismissed by the Strasbourg Court on admissibility grounds, namely that it was manifestly ungrounded. After the European Court of Human Rights underwent a decisive shift in its jurisprudence in the mid-1970s, Norwegian lawyers took notice. Between 1980 and 1992, they cited Strasbourg jurisprudence in 47 cases before the Norwegian Supreme Court and submitted approximately 100 cases to European Commission on Human Rights, even if both strategies initially had little impact. In 1992, Knut Rognlien became the first Norwegian lawyer to win a case in the European Court of Human Rights, which signalled the beginning of a rise of cases from Norway (with different law firms and sometimes NGOs specialising in different sorts of cases), and the more active application of the European Convention on Human Rights by the Norwegian Supreme Court.

Since 1999, which saw the passage of the Human Rights Act that incorporated five international human rights conventions into the Norwegian legal system, international law has had an increasingly prominent position in Norwegian law. Through section 3 of this Act, the incorporated human rights have been given ‘semi-constitutional’ protection, as they will prevail in case of conflict with other Norwegian laws. More recently, as part of the constitutional reform of 2014, the Norwegian Constitution was given a new chapter E with the headline ‘Human Rights’, formally securing the constitutional rank of a wider selection of internationally recognised human-rights provisions.

The constitutional reform also formally enshrined judicial review, the courts’ ‘right and duty’ to review the constitutionality of legislation, administrative decisions and other decisions made by the authorities of the state in the Constitution. However, it is important to note that this provision does not cover the courts’ right to review the legality of administrative decisions. One might argue that the right to this kind of judicial review has been enshrined in the Constitution (perhaps accidentally) after all, when Article 113 is read in light of Article 89 – but that is not a discussion we will expand on in this article.

Moreover, it is notable that the formal recognition of judicial review powers of the Court did not involve a broader discussion on alternative forms of judicial review. For example, in comparable parliamentary democracies, such as Canada, the United Kingdom and New Zealand, ‘weak forms’ of judicial review have been preferred. One example of weak-form review is the ‘notwithstanding clause’ in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Canadian federal and state parliament, by virtue of this provision, can save legislation that has been found unconstitutional by expressly acknowledging that it is inconsistent with the Canadian Charter. Thus, the formal and material power of courts is reduced, as the legislation cannot be overturned for being inconsistent with the Charter, but the parliaments risk symbolic and political embarrassment by circumventing the Charter.

An example of a ‘weak form’ of judicial review in the Norwegian legal system is the constitutional right of the parliament to obtain the legal opinion of the Supreme Court on points of law, and the associated custom of the right of the executive to demand the same in regards to bills or other legal matters. The resulting statement is regarded as an advisory opinion, not a legally binding decision, but the option has rarely been used. The provision was unparalleled in many of the constitutions that served otherwise as examples for the Norwegian constitutional assembly in 1814, such as the Swedish constitution of 1809, the American constitution of 1787, and the French revolutionary constitutions of the same era.

In terms of who can invoke judicial review in Norway, a person who claims to be adversely affected by a law, regulation or decision may take their case to court, and have the constitutionality of the legislation or the legality of the regulation or decision tried before the court through ex post judicial review. Thus, as a main rule, judicial review of the constitutionality of legislation or regulations cannot be demanded on an abstract basis. However, the legislature has allowed for such review of regulation in exceptional cases, for example where NGOs wish to try the legality of regulations that will affect their interests. Some might then raise the question of whether this can also be said to apply to judicial review of the constitutionality of laws, based on the same considerations that led to this change. However, the wording and preparatory works of Article 89 of the constitution, as well as the civil procedure code Article 1–3, would seem to rule out the possibility for this kind of abstract review.

In 2019, the NGO No to the EU (Nei til EU) sued the government on account of the Norwegian accession to the EU agency ACER, contending that the parliament did not abide by the rules for cession of supremacy. The Attorney General claimed that the lawsuit was inadmissible, as the claim entailed a request for abstract judicial review of an act of Parliament, which the abovementioned provisions do not allow. The District Court of Oslo agreed, holding that it would ‘break with the tradition of Norwegian constitutional law’ if the case was deemed admissible.

The focus above on individual rights cases in Norway is telling given that judicial review powers in the country have been most focused on this aspect. While courts can be used as a weapon in inter-branch tug of wars, as discussed above in relation to Germany and the UK, the same cannot be said in Norway. Examples of the parliament using the traditional courts to curb the government’s actions (such as the UK prorogation decision) cannot – to our knowledge – be found. On the contrary, the Norwegian Supreme Court has stated that it would apply a less intense scrutiny in relation to separation of powers, meaning that parliament’s own interpretation of the constitution will be given more weight. Nonetheless, power struggles between the parliament on one side, and the King and his government on the other, were the basis for the majority of the eight Riksrett cases that took place in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Riksrett, however, is an ad hoc court, and cannot be viewed as part of the traditional court system. The Norwegian courts, including the Supreme Court, traditionally respect the will of the legislator and the discretion of the executive. They have historically abstained from ‘meddling’ in political questions. The exception has become the rights guaranteed the citizens by parliament through the constitution and international treaties.

Even so, the Norwegian Supreme Court has been more cautious than many of its counterparts in interpreting and applying individuals’ constitutional rights. A good example is the field of social rights. In the case of Rt-2001-1006, on p. 1015, Justice Stang Lund noted that when international human rights treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) are domesticated without being transformed into a standard statute, the Court ‘must take a position on whether the actual provisions provide individual rights’ or instead ‘express an objective or require State parties to meet a required goal or minimum standard’. The provisions in the treaties concerning ‘more traditional human rights’ were deemed concrete enough to generate individual rights, but he continued by stating that ‘questions can be asked whether immediate application for example arises for specific provisions in the ICESCR’.

However, in many European courts, the position is different. In Germany, Italy, Portugal, Finland, Hungary and Latvia, these rights have been found justiciable. For example, across the Baltic Sea in Latvia, the Court recognised it had a fundamental duty to ‘determine whether the scope of the freedom of action exercised by the Saeima (Parliament) conforms to the provisions’ of all treaties incorporated in the constitution, including the ICESCR. In 2009, by way of illustration, the Court considered whether a cut to full pensioners by 10 percent, and working pensioners by 70 percent, in the midst of the global economic crisis constituted a violation of the right to social security in the ICESCR. The Court applied a proportionality test. It found first that ‘restrictions’ on pensions had a ‘legitimate end’ in solving ‘financial problems in the social budget’, especially because in a time of a recession, the State must be granted ‘[r]easonable freedom’ to take swift and concerted action.

The final result, nonetheless, was otherwise. After inviting and assessing submissions from 19 different government and non-government actors, the pension cuts were found to have failed the second and third prongs of a proportionality test. The Court held that neither the cabinet nor the Parliament had carried out ‘an objective and well-balanced analysis of the consequences’, nor had they considered ‘less restrictive means for the attainment of the legitimate end’. On the evidence, the Court found that (1) the minimum core of the right was threatened for poorer pensioners and (2) the different social benefits were highly arbitrary. Yet, the court was reflexive in its remedy. It provided the government five years to repay pensioners, with the poorest pensioners to be prioritised in the process. Although, it should be noted that the Court also found that working pensioners had legitimate expectations to an appropriate transitional period. This approach is not uncommon in Norway with a substantial jurisprudence on retroactive legislation that covers social security cutbacks.

The Norwegian experience of judicial review of legislation has thus bookended its development and maturation. The Norwegian Supreme Court was one of the first to establish such power, but one of the last to engage in its regular usage. The adoption of the new Norwegian bill of rights in 2014 has spurred a rise in cases citing human rights, and interpretations made by the UN Committee of the Child and the UN Committee on Human Rights have been given substantial weight. However, the future direction of the court concerning social rights challenges to legislation remains unclear. For example, in a recent case concerning the right to work in the constitution and ICESCR, the District Court of Oslo ignored the relevant jurisprudence of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

5. Constitutional amendment

5.1 Replacement versus amendment

Finally, we turn to the amendment of constitutions. This process should be distinguished from replacing constitutions, which is surprisingly common. Since 1789, there have been an estimated 742 new national constitutions and the average life span of a constitution is only 19 years. Revolutions and coups are common reasons. The first French constitution was implemented in 1791, after the monarchy was overthrown, instituting a new social order. The revolutions morphed and new constitutions were created in 1793, 1795 and 1799, and after Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power, two more saw the light of day in 1804 and 1814. The island of Hispaniola, home to the Dominican Republic and Haiti, holds the record, accounting for nearly 7 percent of the world’s constitutions.

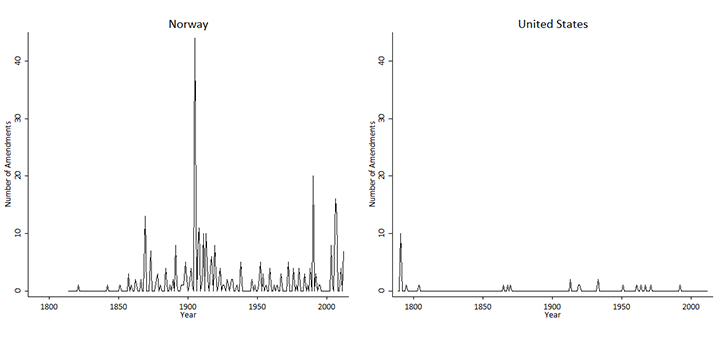

Figure 3

Comparing the Norwegian and US Constitutions – Amendments173. Source: Tom Ginsburg (n 6), 231.

In this respect, Norway’s constitution is unique for its survival. It has not been replaced, but it has been amended – and frequently so. Unlike the US constitution, the Norwegian constitution is no exception to the general pattern of frequent amendment: see Figure 3. Holmøyvik has calculated that there have been 318 substantial amendments or new provisions between 1814 and 2018. While core elements like basic human rights, popular sovereignty and the separation of powers have stood the test of time, other provisions have not. This is not dissimilar to many Western European countries, where amendment is relatively common. However, it is important to note that one of the reasons for the many amendments to the Norwegian constitution is the detailed regulation of the electoral system: each time a change in the number of representatives, electoral districts etc. is desirable, there must be a corresponding constitutional amendment.

It is worth noting that it is not always easy to distinguish between amendment and revision/replacement. An amendment is commonly understood as the correction or improvement of the existing provisions ‘in light of new information, evolving experiences or political understandings’. However, in some cases the changes are so comprehensive that they might more accurately be described as a constitutional revision, entailing a change in the basic procedural or substantive framework for the process of democratic self-government. Moreover, which category a desired change falls into might influence the formal requirements that need to be met to make the change. Moreover, constitutions may change simply, and subtly, through judicial, executive and parliamentary interpretation. In the Norwegian tradition, the constitution is interpreted in light of social developments. Thus, while section 12 of the constitution stipulates that the King in counsel chooses his cabinet, in practice the Prime Minister chooses and the King formally appoints.

5.2 Process for amendment

In comparing jurisdictions, we can ask how can constitutions be amended, by whom and on what grounds? There are several ways to formally amend a constitution, and we will look at the three principal models: (1) a parliamentary vote; (2) citizen-initiated referendum; and (3) institution-initiated referendum. Requirements can also vary. A quorum or minimum number of parliamentarians or citizens might be required for a vote to occur. A threshold might exist for the actual vote: for example, a simple majority or supermajority (eg two-thirds) in parliament, or a majority in a set number of states in a federal system. There may also be restrictions on which parts of the constitution can be amended, for example through so-called eternity clauses, of which the Norwegian spirit and principles in Article 121 is an (atypical) example.

Across countries, these specific and technical requirements vary significantly, and which is chosen exerts great influence on the likelihood of success. Moreover, as with judicial review, the underlying debate on the virtues of different amendments affects local design choices. Direct forms of constitutional amendment such as a referendum may have greater democratic legitimacy but they provide less room for more nuanced decisions, as can occur in a parliamentary model of amendment. Moreover, low thresholds for making and securing proposed constitutional amendments enhances contemporary democratic participation but may come at the expense of the rights of different minority interests or stable government. This normative debate take on a particular importance since constitutional amendment is commonly understood as part of foundational constituent power (pouvoir constituant) rather than constitutive power (pouvoirs constitués) - to follow the French revolutionary Abbé Sieyès: Constitutional amendment is distinct from ordinary legislation and draws on the constituent power, residing in the people as a collective unit, rather than the parliament as a representative (the constituted power).

In a representative democracy, the people elect representatives to make decisions on their behalf through their work in parliament. In some states, this will include amending the constitution. Constitutional amendment through a parliamentary vote is the Norwegian approach, and the process is as follows: A bill containing the change must be put before parliament and publicly announced in the first three years of the four-year parliamentary period. Then, in the first three years in the next parliamentary period, the bill is voted over, and must pass with a supermajority (two-thirds). There are few substantive requirements. The only real restriction is that the amendment cannot contradict the principles embodied in the constitution or alter the spirit of the constitution. This relatively simple process, neither with many requirements nor the particular involvement of many ‘veto players’, makes amendment more likely.

The US model of parliamentary voting, however, is far more complicated. The constitution provides that an amendment may be approved either by Congress, with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of the State legislatures. None of the 27 amendments to the constitution have been approved by constitutional convention. Prominent examples of successful amendments include free speech (1791), the right to bear arms (1791), equal protection (1868), women’s right to vote (1920) and presidential succession in case of severe disability (1967). However, many proposals have never been ratified by the states. For example, in 1926 an amendment was proposed granting Congress the power to regulate child labour. This amendment is still outstanding, having been ratified by only 28 states, the last in 1937.