Norwegian Cartels: Law, Policy, Registration and Practice under the Price and Competition Act between 1954 and 1993

Publisert 13.10.2020, Oslo Law Review 2020/2, Årgang 7, side 84-104

Twentieth-century cartel registers, operated in a number of countries predominantly from around 1950 to the early 1990s, are a new international field of research. Such registers provide empirical data for research in a variety of fields, including law and economics. This article gives an overview of Norwegian cartel regulation, policy, registration and practice from 1954 to 1993, that is the period in which the Norwegian Price and Competition Act 1953 remained in force. To do so, we combine legal sources, historical accounts and a unique dataset collected and coded from the Norwegian Cartel Registry. In 1957 and 1960, vertical and horizontal price fixing respectively was generally prohibited. Using Norwegian cartel register data, we discuss whether and how these regulatory changes affected Norwegian cartel activity and organisation. We find that Norwegian cartels were long-lived, and that the typical cartel was a pure pricing cartel. Notwithstanding a lenient exemption policy, the prohibitions reduced the number of pricing cartels. The reduction was largely caused by the composition of entering cartels, as well as pricing cartels leaving the market. Very few cartels seemingly changed their cartel agreements. Our data suggests that established cartels were, perhaps surprisingly, non-flexible with regard to alternative modes of anti-competitive coordination.

Keywords

- Norwegian cartels

- cartel register

- competition law and policy

1. Introduction

This article describes and analyses Norwegian cartel regulation, policy and practice under the Price and Competition Act 1953 that remained in force from 1954 to 1993. We give particular attention to two significant changes in Norwegian competition law, when vertical and horizontal price fixing was generally prohibited by regulation in 1957 and 1960, respectively. Using data from the Norwegian Cartel Registry operated by the Norwegian Price Directorate (Prisdirektoratet), we discuss whether and how these regulatory changes affected Norwegian cartels and cartel organisation.

Under contemporary competition law and policy, anti-cartel enforcement is a top priority in most jurisdictions. Cartel activity, here broadly defined as collusion between undertakings only to fix prices, reduces output, shares markets or customers, reduces competition and causes harm to the economy and consumers. Today, cartels are therefore illegal and severely sanctioned.

Under Norwegian law, cartels and other forms of anti-competitive collusion became prohibited from 1 January 1994. On that date, the Competition Act 1993, as well as the Agreement on the European Economic Area (EEA Agreement) and the EEA Implementation Act, entered into force, and the new Norwegian Competition Authority (NCA) was established. Ten years later, the Competition Act 2004 introduced a general prohibition on anti-competitive agreements (§ 10), mirroring Article 53 of the EEA Agreement and Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). Under current Norwegian competition law, cartel activity contrary to section 10 of the Competition Act 2004 (or Article 53 of EEA Agreement), may trigger administrative fines against participating undertakings and criminal sanctions for individuals, and may result in claims for damages from injured parties. The NCA labels cartel activity as competition crime.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, however, Norwegian cartel regulation and policy differed significantly from the law and policy after 1993. For much of that century, Norwegian price and competition authorities tended towards price control rather than competition regulation and policy. A lenient approach was taken towards cartels and other private competitive regulations, which were perceived as stabilising forces in the economy. Notably, however, in 1957 and 1960 vertical price fixing (between undertakings operating at different levels of the distribution chain) and horizontal price fixing (between competitors) were generally prohibited by Regulations. The Regulations allowed for exemptions to be granted by the Norwegian Price Directorate. Cartelisation on other parameters than price was not prohibited.

A register of legal cartels and restrictive competitive practices was operated by the Norwegian price and competition authorities from 1920 to 1993. In a global perspective, the Norwegian Cartel Registry was the first to be established, and the longest operated. Under the Price and Competition Act 1953, registration was mandatory and the register was made publicly available. The Price Directorate also published summaries of the entries to the Registry in its gazette Pristidende, as well as in ten different volumes irregularly issued from 1955 to 1991.

The published entries in the Norwegian Cartel Registry provide a unique data set on Norwegian cartel activity. The Cartel Registry provides information on the cartels that were formed, which sectors they operated in, (for most) how many participants they had, which (anti)competitive restrictions they agreed upon, how they ensured compliance, (for most) how long they lasted, how they functioned, and more.

Cartel register analyses have become a new international field of research, particularly within the field of economics. Hyytinen, Steen and Toivanen initiated cartel register research in Finland in 2006 and have since published several articles on cartels using data from the Finnish Competition Authority’s archive of cartels. Austrian registered cartels have also been coded and analysed. Fellmann and Shanahan provide an introduction to the field, as well as an overview and analysis of cartel registers around the world. Cartel registers provide empirical data for research on how cartels in various industries and sectors are formed, organised, disciplined and terminated, under varying market circumstances and regulatory regimes. Besides their historical documentary value, information gathered from such registers is used in the development of cartel theory and provides insights for modern competition law enforcement towards cartel detection and investigation.

The aim of this article is to provide an overview of Norwegian cartel regulation, policy and practice in the period from 1954 to 1993, and analyse whether the Regulations generally prohibiting vertical price fixing (in 1957) and horizontal price fixing (in 1960) affected how cartels operated, and how cartelists responded and adapted to these regulatory changes. We do this by combining legal sources, historical accounts, and data from the Norwegian Cartel Registry. We also compare our Norwegian cartel data to cartel studies in other jurisdictions, in particular Finland and Austria.

Our findings on Norwegian cartel demography resemble studies on comparable registers. Pricing cartels, however, were much more common in Norway than in other jurisdictions, amounting to two-thirds of the cartels in the Norwegian cartel population. The second most common cartels were quota cartels, representing one-tenth of the Norwegian legal cartel population. When analysing the dynamic development of cartel types, we find that the fraction of pure pricing cartels, and in particular the share of fixed price cartels, decreases over time. The dynamic changes we observe are perhaps nevertheless less significant than what one would expect from the legislative changes towards price coordination introduced in 1957 and 1960. A plausible explanation is the Norwegian price and competition authorities’ liberal exemption policy.

The dynamic changes were due to the composition of new cartels, and even more to the exit of pure pricing cartels. Only to a very limited degree do we see cartels altering their cartel agreements and continuing their cartel activities in new forms. This suggests that pricing cartels had a limited degree of flexibility to change their way of cooperation, even within a legal framework where they could lawfully form cartels. From the point of view of cartelists, our data may suggest that price coordination may be substituted by coordination on markets, customers or production quotas only to a limited extent.

With a bearing on modern anti-cartel enforcement, the latter result may indicate that pricing cartels are less flexible and robust in terms of cooperation modes. If the substitutability towards other modes of cooperation such as market sharing or quota cartels is particularly low, this also suggests that pricing cartels might be both more efficient in raising profits and, as such, even more detrimental to welfare than other cartel types.

The article is outlined as follows: in section 2, we give a legal and historical overview of Norwegian cartel regulation and policy from 1954 to 1993; section 3 presents our cartel register data and provides an empirical overview of Norwegian cartel practices; in section 4, we introduce the regulatory prohibitions on vertical and horizontal price fixing, and discuss the price and competition authorities’ policies under these regulatory restrictions; based on our cartel register data, section 5 empirically analyses the regulatory impact of these changes on Norwegian cartel practice; section 6 provides some concluding remarks.

2. Norwegian cartel regulation, registration and policy 1954-1993

2.1 Introduction

In this section, we provide a bird’s-eye view of Norwegian cartel regulation, registration and policy between 1954 and 1993. We present the Price and Competition Act 1953, and briefly outline Norwegian competition policy, with a particular focus on the Cartel Registry, over the four decades (from 1 January 1954 to 31 December 1993) in which the Act was in force. The objective is to provide context and background to our empirical and statistical analysis of the Cartel Registry.

2.2 The Price and Competition Act 1953

The Norwegian Cartel Registry may be traced back to the years after the First World War. The war led to increased prices for food and consumer goods also in Norway, which in turn sparked a series of Acts and Regulations on price control between 1914 and 1918. Information on price control was published in the gazette Pristidende. The first issue came out on 9 January 1918, and by the end of 1918 the gazette was printed in 27,000 copies. In 1920, notification of monopolies, large undertakings and private competitive regulations to the Price Directorate was required by law. The so-called ‘cartel register’ was thereby established. By 1921, the Registry contained 418 associations of undertakings, 56 large undertakings and 51 private agreements on competition.

Through the Trust Act 1926, Norway became one of the first European countries to enact legislation on the control of cartels and competitive restraints. The Act has been described as a ‘third way’ between the contemporary strict US law and policy on trusts and cartels and the more lenient German approach. The Trust Act 1926 established two new institutions for the control of competition restraints and prices. The Trust Control Office was responsible for maintaining a register of competitive restraints, while the Trust Control Council decided on substantive matters. The Trust Act prohibited unfair prices (§ 13). The Trust Control Council also had competence to intervene against refusals to deal (boycotts) (§ 21), exclusivity agreements (§ 22), and discriminatory prices and conditions (§ 23). The Cartel Registry under the Trust Act 1926 was based on mandatory notifications of associations, agreements or arrangements between undertakings, having as their ‘object or effect’ the regulation of price, production or trading conditions affecting the market conditions in Norway (§ 6). Public access to the Registry could exceptionally be granted by Trust Control Office (§ 7).

The Second World War resulted in detailed price regulation from September 1939 to May 1945. Extensive price regulation continued in the early post-war years, pursuant to the provisional Regulation of 8 May 1945 and the Temporary Price Act 1947. Registered cartels were involved in the implementation of regulated prices.

The difficulties in recreating competition after 1954, when state price regulations were abolished, have further been attributed to the close involvement of the cartels in implementing the detailed price regulations from 1939. The Price and Competition Act 1953 came into force on 1 January 1954 and remained applicable until 31 December 1993. It was enacted after what has been described as one of the toughest legislative political battles of the post-war era.

The 1953 Act provided the authorities with broad and discretionary competences. The control of both prices and competition was regulated, as had been the case with the Trust Act 1926. Control over dividends was also initially regulated, but those provisions were repealed in 1960.

The objectives of the Price and Competition Act 1953 were broadly defined (§ 1). The Act’s main objective was to ensure full employment and the effective use of production resources, counteract deposition crises, and promote a reasonable distribution of the national income. Secondary objectives were the prevention of unreasonable prices, profits and business practices conditions, the prevention of improper distribution of dividends, and safeguarding against competitive practices that were unreasonable or to the detriment of the public interest.

On substantive matters, the Act contained general prohibitions and also provided the Norwegian price and competition authorities with the competence to intervene against market misconduct. For example, § 18 set out a general prohibition on unfair prices and trading conditions, § 24 provided the authorities with general competence to regulate prices, and under § 42 the authorities could prohibit or amend private competitive regulations considered harmful, unfair or contrary to the public interest. In 1988, the competition authorities were also given the power to intervene against anti-competitive mergers and acquisitions (§ 42 a).

Notification of private competitive regulations to the Price Directorate was required by law. Pursuant to § 33, undertakings were obliged to notify agreements, arrangements or regulations by associations of undertakings on binding or recommended sales prices, profits, cost calculations, business conditions, production and output. Competitive regulations were not to be implemented until the Price Directorate had been notified (§ 36). Additional notification requirements applied for large undertakings (§ 34).

The Cartel Registry was operated by the Price Directorate (§ 35). Significant efforts were made to update the Registry, which had decayed during the period of comprehensive price regulation after 1939. A Regulation on the registration of competitive regulations and large undertakings specified that the Registry should be publicly accessible. The Price Directorate was also required to publish an official gazette (Pristidende) containing the main features of the registered competitive regulations, as well as subsequent amendments. Undertakings and associations of undertakings were required to subscribe to Pristidende and to make it accessible to their customers.

On 1 January 1994, the Price and Competition Act 1953 was replaced by the EEA Agreement, the EEA Implementation Act and the Competition Act 1993. Pursuant to the EEA Agreement and the EEA Implementation Act, the general prohibition on anti-competitive agreements (Article 53 EEA Agreement) became Norwegian law. The Competition Act 1993 set out a narrower legislative objective of ensuring effective usage of society’s resources by providing for workable competition (§ 1). Among other things, the Act prohibited price fixing (§ 3-1), bid rigging (§ 3-2) and market sharing (§ 3-3), as well as provided the Norwegian Competition Authority with a general competence to intervene against anti-competitive practices (§ 3-10) and acquisitions of undertakings (§ 3-11). Typical cartels were accordingly prohibited, and the Cartel Registry was discontinued.

In 2004, the Competition Act 2004 replaced the 1993 Act, and the EEA Competition Act also entered into force. The Competition Act inter alia contained prohibitions on anti-competitive agreements (§ 10) and abuse of dominance (§ 11), equivalent to Articles 53 and 54 of the EEA Agreement. The Competition Authority was also given the power to issue administrative fines against undertakings violating competition rules (§ 29). The EEA Competition Act implemented rules on the enforcement of EEA competition law.

2.3 Price and Competition Policy 1954–1993

This subsection provides a basic overview of Norwegian price and competition policy over the four decades in which the Price and Competition Act 1953 remained in force. To support our subsequent empirical analyses of cartel register data, we apply a periodic approach in which distinct periods with different policy characteristics are distinguished from each other. The outline is based on secondary sources, first and foremost Espeli, the Norwegian Official Report (NOU) 1991:27, as well as on a brief account of the Price Directorate’s history between 1917 and 1992.

To describe Norwegian competition policy in the second half of the twentieth century, Espeli distinguishes four periods (1954–1960, 1961–1971, 1972–1980, and 1981–1990), while NOU 1991:27 and the Price Directorate both operate with three distinct periods (1954–1971, 1972–1980, and 1981–1990). All three accounts describe how the preferred policy shifts between price regulation and competition policy over this period. The pendulum swing between price regulation and competition policy reflected the conflicting policy objectives between short-term price stability and long-term economic efficiency. Placing stronger emphasis on the regulatory prohibitions on vertical and horizontal price fixing introduced in 1957 and 1960, Espeli’s periodisation serves our objectives better. However, it should be borne in mind that transitions between periods took place gradually, without exact demarcations.

The first period (1954–1960), identified and described by Espeli, is labelled as ‘from detailed price regulation to competition policy’. This period runs from the entry into force of the Price and Competition Act 1953 until 1960. From 1954, price regulations were gradually abandoned as output increased and goods became more accessible. In parallel, competition policy to further economic efficiency became more important. Both Espeli and NOU 1991:27 argue that the regulatory prohibitions on vertical (1957) and horizontal (1960) price fixing altered the character of the Act to an extent, from reliance on discretionary intervention by the competition authorities to reliance on statutory prohibitions. The Regulations prohibiting vertical and horizontal price fixing represented a policy shift towards competition policy, away from detailed price regulation.

Notifications of private competitive restrictions had not been a priority since 1939, partly due to the detailed price regulation during the war. In the early post-war years the Price Directorate therefore had limited knowledge of existing private competitive arrangements. To update the Cartel Registry, the Regulation on the registration of competitive regulations and large undertakings was issued in 1954. The first volume summarising the registered competitive arrangements and practices was published in 1955.

The second period (1961–1971) is labelled by Espeli as ‘the decade of exemptions’. According to Espeli, the decade is characterised by a lack of political interest in competition policy, limited enforcement of the regulatory prohibitions on vertical and horizontal price fixing, and a lenient policy of granting exemptions from these regulatory prohibitions. In NOU 1991:27, it is argued that the liberal exemption policy reflected the authorities’ positive view towards (anti)competitive cooperation between Norwegian undertakings, in a period characterized by freer trade, international competition and the establishment of the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). Towards the end of the period, temporary price regulation again became a preferred policy instrument, this time to combat inflation.

During the third period (1972–1980), which was characterised by frequent price and profit regulations, there were twelve periods of temporary ‘price freezes’, eight of which covered all sectors of the economy. In total, these temporary price freezes lasted for two-thirds of the time period. The price and competition authorities’ main priority was to monitor and enforce the price regulations in order to reduce inflation. Competition policy was not on the agenda. By the 1980s, however, the pendulum swung once again, this time away from price regulation and towards competition policy, following the international trend towards free market solutions.

The final period (1981–1990) has been labelled ‘the renaissance and expansion of competition policy’. In the 1980s, exemptions from the prohibitions on vertical and horizontal price fixing were reconsidered, and in many cases revoked, for example for liberal professions. State monopolies were also opened to competition, and in 1988 merger control became part of the competition policy toolbox. In 1989, a policy was introduced to update the information in the Cartel Registry.

The Cartel Registry was nevertheless discontinued with the entry into force of the Competition Act 1993. NOU 1991:27 pointed out that the Price Directorate’s interventions had rarely been triggered by the notification system. It also noted that mandatory notification had not been an enforcement priority, and that maintaining the Cartel Registry would require significant administrative resources. The Ministry of Labour and Administration agreed with the recommendations in NOU 1991:27, and held that the system based on general, mandatory notification and subsequent registration on competitive restraints should be abandoned.

In the next section, we look more closely into the Norwegian Cartel Registry, in particular at how registered, legal cartels maximised their profits and how they were organised from 1954 onwards.

3. Norwegian cartel register data and cartel practices 1954–1993

3.1 Introduction – Norwegian cartel register data

As outlined above, although the Norwegian Cartel Registry dates back to 1920, the Registry only became publicly accessible from 1955 onwards. Undertakings were not only required to notify new arrangements, but also amendments to previously notified arrangements. The Price Directorate published summaries of the registered arrangements in Pristidende. Moreover, summaries of registered, amended and terminated competitive arrangements and practices were also published in ten different volumes for the followings years: 1955, 1957, 1962, 1967, 1972, 1977, 1983, 1989, 1990 and 1991. The summaries provide information on how the cartels cooperated to maximise profits, how they were organised, when they were established, and, for most of them, when they were terminated.

The summaries from these ten volumes provide the basis for our cartel register data. There are 790 registered cartels in this period. Our analyses are based on 492 of these, which resemble the typical cartels that we find in the empirical economic literature. We have further coded the cartels’ organisational structures and modes of cooperation. Using the typology developed by Hyytinen, Steen and Toivanen in their studies on Finnish cartels, four mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive cartel types have been coded: pure pricing, pure allocation, quota, and mixed price-allocation cartels. In addition, the pricing cartels’ disaggregated pricing rules that were heterogeneously affected by changes in the legislation over the legal cartel period have been coded. Due to the existence of updated descriptions of the cartel contracts from the cartel summaries over the period 1955 to 1991, changes in cartel typology over time have also been coded. This provides a dynamic demography on the cartel typology development over time, both in terms of entering and exiting cartel types, but also in terms of changes in typology for continuing cartels.

3.2 Norwegian cartel practices – empirical overview

Our focus here is on 492 Norwegian cartels over the period between 1955 and 1989. Pure pricing cartels only use pricing clauses and/or payment rules. Pure allocation cartels use only area-based market allocation and/or non-area-based market allocation clauses. Quota cartels may have pricing clauses and/or payment rules in addition to a quota clause, whereas mixed price-allocation cartels can, in addition to pricing clauses and/or payment rules, use area-based market allocation and/or non-area-based market allocation clauses, but they do not use quota clauses.

In Table 1 we show how the four ways of maximising joint profits are used by Norwegian cartels:

| Pure pricing | Pure allocation | Mixed price-allocation | Quota | |

| Norwegian cartels (share) | 67.9 % | 7.1 % | 4.1 % | 11.6 % |

| Norwegian cartels (n) | 334 | 35 | 20 | 57 |

| Members (median) | 14 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Duration (median) | 23.5 | 21 | 18.5 | 20 |

| Local (mean) | 54 % | 11 % | 5 % | 23 % |

| Horizontal (mean) | 86 % | 94 % | 95 % | 98 % |

| International (mean) | 0 % | 34 % | 5 % | 4 % |

| Export (mean) | 0 % | 11 % | 0 % | 5 % |

The most typical cartel is a pure pricing cartel, accounting for two-thirds of the Norwegian legal cartels. Around one in ten cartels are quota cartels. Some cartels had not agreed on any of the major clauses we present above. Of the total sample of 492 cartels, 9.3% of the Norwegian cartels did cooperate on some issues, but not on price, quota or market allocation.

Compared to Finnish registered cartels from the same historical period, Norway had a much larger fraction of pricing cartels: 68% against 46% in Finland. Norway also had relatively more quota cartels (12%), which in Finland had a relative share of 8%. A particularity in the Finnish cartel population, however, is a large share of pure allocation cartels (27%), which mostly consisted of non-area-based bilateral cartels that often stipulated that the members were to specialise in one way or another, or where the contracting parties simply agreed ‘not to compete’. These cartels seem to adopt a home turf principle in which the colluding firms engage in mutual avoidance by allocating the product, production or some other amenity amongst themselves instead of allocating geographical markets or customers. Hyytinen, Steen and Toivanen argue that these cartels resemble today’s mergers, but in the Norwegian cartel population such cartels are very rare (11 in total). If we adjust for these ‘merger’ cartels in the Finnish sample, the two cartel populations become more similar.

Table 1 also contains cartel characteristics across various cartel types. Pricing cartels are both substantially larger and last longer than the other cartel types. They are much more often local, somewhat more often vertical (14% as compared to 2–5% for the others), and they are never international or export-oriented. One in four quota cartels are local, and a few are international and export-oriented. In this regard, the pure allocation cartels stand out, where one in three cartels are international, and one in ten are export-oriented.

Regardless of type, Norwegian cartels are long-lived. The median varies between 18.5 and 23.5 years. Not surprisingly, legal cartels last longer than illegal cartels. For instance, Levenstein and Suslow found that the average duration of illegal cartels varied between four and ten years.

To understand how legislative changes have affected the composition of cartel types over time, we decompose the pure pricing cartels into sub-categories of disaggregated pricing clauses. In particular, we distinguish cartels that coordinated fixed prices and those that coordinated only suggested prices. Furthermore, we look separately at those that had payment rules. In Table 2, except for the last two characteristics (international and export), we have thus decomposed the pure pricing numbers from Table 1.

| Pure pricing | Fixed price rule | Suggested price rule | Payment rule | |

| Norwegian cartels (share) | 68 % | 48 % | 18 % | 33 % |

| Norwegian cartels (n) | 334 | 238 | 87 | 163 |

| Members (median) | 14 | 8 | 26 | 7 |

| Duration (median) | 23.5 | 21.5 | 39 | 22 |

| Local (mean) | 54 % | 44 % | 87 % | 16 % |

| Horizontal (mean) | 86 % | 84 % | 97 % | 87 % |

The second column of Table 2 simply replicates the relevant part of column 2 of Table 1. Pure pricing represents all cartels that have either a price rule, or a payment rule. The next three columns comprise the same numbers for pricing cartels disaggregated to three sub-types: cartels having a fixed or suggested price rule, and the last column describes all cartels that have a payment rule. Note that the three sub-categories are not mutually exclusive and thus the disaggregated type-shares sum up to more than the total share of pure pricing cartels.

When we decompose the pure pricing cartels, some patterns become visible. First, suggested price cartels are larger than the others, and in particular much larger than fixed price cartels. Also, cartels imposing payment rules are smaller. As anticipated, duration also stands out, in the sense that the suggested price cartels last longer. Taking part in a fixed price cartel was, after all, made illegal for most industries and sectors in 1957 and 1960 (see below). Another observation is that suggested price cartels are nearly always local (87%), as opposed to cartels having payment rules, which are national in 84% of the cases. In line with the prohibition on vertical restrictions and fixed mark-up regulation that was imposed in 1957, we also note that the suggested price cartels are more often horizontal than the other pricing cartels.

Before we look empirically at the dynamic development of our Norwegian registered cartels, we take a closer look at the legislative changes that took place in this period.

4. Norwegian regulation and policy on vertical (1957) and horizontal price fixing (1960)

4.1 Introduction

In this section, we present the regulatory prohibitions on vertical (1957) and horizontal (1960) price fixing, as well as the competition authorities’ enforcement and exemption policies towards these prohibitions. The objective is to provide context and background to our further empirical analysis of the impact of the prohibitions on Norwegian cartel practices (see section 5 below). Vertical price fixing here broadly refers to arrangements between undertakings operating at different levels of a distribution chain that determine or affect the buyer party’s resale prices, colloquially referred to as resale price maintenance (RPM). Horizontal price fixing broadly refers to arrangements between (actually or potentially) competing undertakings, to coordinate or affect sales prices.

4.2The Regulation on vertical price fixing of 1957

The Price and Competition Act 1953 did not contain any general prohibitions on anti-competitive practices. However, as previously explained, the competition authorities were given broad discretionary competences to prohibit anti-competitive arrangements in individual cases or by regulation (§§ 24 and 42).

Vertical price fixing was prohibited by Regulation no 8782 of 18 October 1957 on so-called supplier restrictions, which entered into force on 1 May 1958. In the preparatory documents leading up to the Regulation, the Price Directorate noted that vertical price fixing could be presumed to lead to higher consumer prices and should therefore be prohibited, albeit subject to the possibility of exemptions.

The Regulation set out prohibitions on both individual and collective supplier restrictions (§§ 2 and 3). Individual supplier restrictions were those set by individual suppliers, while collective supplier restrictions were set by associations of suppliers or groups of suppliers. Supplier restrictions were defined as fixed or recommended resale prices (§ 1). However, recommended resale prices were only prohibited when part of collective agreements. The same applied to vertical restrictions by foreign suppliers (§ 4). The Regulation also prohibited buyer initiated supplier restrictions (§ 6).

Exemptions followed from §§ 8 and 9 of the Regulation. Supplier restrictions ordered by law or parliament decision, were exempted (§ 8). Moreover, the Price Directorate was given discretionary competence to grant exemptions in individual cases when required by special considerations and in conformity with public interests (§ 9, first paragraph). Exemptions could be made conditional (§ 9, second paragraph).

Notably, and by comparison, the Norwegian Regulation on supplier restrictions of 1957 was enacted the same year as the signing of the Treaty of Rome, which established the European Economic Community. The Treaty of Rome prohibited anti-competitive agreements (Article 85 EEC, now Article 101 TFEU) and abuse of dominance (Article 86 EEC, now article 102 TFEU). In 1966, the Court of Justice of the European Communities firmly established that the prohibition of anti-competitive agreements was applicable also to vertical agreements. Under contemporary EU/EEA and Norwegian competition law and policy, vertical agreements containing resale price maintenance (RPM) arrangements may be contrary to Article 101(1) TFEU, Article 53(1) EEA Agreement and § 10, first paragraph of the Competition Act 2004. Fixed and minimum RPM qualify as ‘hardcore restrictions’ that remove the benefit of the Block Exemption on Vertical Agreements. The possibility of individual exemptions pursuant to Article 101(3) TFEU, Article 53(3) EEA Agreement and § 10, third paragraph of the Competition Act 2004, is nevertheless open.

4.3 The Regulation on horizontal price fixing of 1960

Horizontal price fixing was prohibited by Regulation No 9153 of 1 July 1960 on competitive restrictions on prices and profits, which entered into force on 1 January 1961. In preparing for the Regulation, the Price Directorate argued that despite industry participants attempted to justify widespread vertical price fixing as a means to preserve orderly market conditions, the most apparent effect was higher prices. The Price Directorate also rejected the argument that horizontal price fixing was necessary in the face of increased competition from foreign undertakings. The need for general exemptions for certain industries, and individual exemptions under specific circumstances, was nevertheless recognised.

The prohibition of horizontal price fixing covered any competitive coordination by associations or groups of undertakings on prices, profits, discounts or bonuses (§ 1, first paragraph). Moreover, the Regulation prohibited coordination of prices and conditions in relation to tendering for contracts (§ 2). Indirect means of inducing price fixing or enforcing price fixing arrangements were explicitly prohibited (§ 3). Foreign undertakings and Norwegian members of foreign associations of undertakings operating in Norway were also explicitly covered by the Regulation (§ 4). While the Regulation prohibited price fixing, it did not prohibit anti-competitive coordination on, for example, markets, customer groups, output or quotas.

Groups of undertakings were defined broadly as any group of two or more undertakings established by agreement or mutual understanding (§ 7). By comparison, the concept of ‘associations of undertakings’ in the contemporary prohibition of anti-competitive coordination (Article 101 TFEU, Article 53 EEA Agreement, and § 10 Competition Act 2004) has similarly been described by the Court of Justice of the European Union as groups with collective interests that intend or agree to coordinate their conduct through decisions of the association.

Most types of price coordination, almost regardless of form, were covered by the prohibition. The Regulation stated that coordination of prices, profits, discounts and bonuses was prohibited regardless of how the coordination was manifested, whether through written or informal agreements, decisions or understandings (§ 1, second paragraph). The broadly defined means of coordination covered by the Regulation notably mirrors today’s Article 101 TFEU, Article 53 EEA Agreement and § 10 Competition Act 2004, which cover not only agreements and decisions of associations of undertakings, but also ‘concerted practices’.

General exemptions were set out in § 5 of the Regulation, according to which the prohibitions did not apply inter alia in relation to export or to the agriculture, forestry and fishing sectors. Individual exemptions could be granted, pursuant to § 6, if the competitive restraints were necessary for technical or economic cooperation and could lead to a reduction of costs, improved products or rationalisation. Exemptions could also be granted if necessary to protect industries against unreasonable or harmful competition, or if required by special considerations and in conformity with public interests. Again by comparison, an exemption rule is today found in Article 101(3) TFEU, Article 53(3) EEA Agreement and § 10, third paragraph of the Competition Act 2004.

4.4 Competition policy on vertical and horizontal price fixing

In this subsection, we briefly describe the Norwegian policy on vertical and horizontal price fixing pursuant to the Regulations from 1957 and 1960, before we go on to analyse the dynamic impact of the Regulations on registered cartel activities in more detail.

As to vertical price fixing, the Price Directorate noted that such arrangements likely covered a very substantial share of the markets for consumer goods. Espeli points out that prior to the Regulation on vertical price fixing of 1957, vertical price restrictions were widespread for consumer goods such as foods (chocolate, sugary products, biscuits, crispbread), boots and shoes, construction materials and hardware, pulp and paper products, light bulbs, cement, books, gramophone records, newspapers and magazines. For horizontal price fixing, Espeli notes that construction materials, pulp and paper, textiles and foods (beer, tobacco, chocolate) were particularly strongly affected by private competitive restrictions, as well as being shielded from foreign competition by tariffs and import restrictions.

With regard to individual exemptions, the Price Directorate initially favoured a restrictive policy, both in relation to vertical and horizontal price fixing. The Regulation on vertical price fixing resulted in a large number of notifications of termination or amendments of vertical agreements. The Price Directorate initially also received a large number of applications for exemptions. According to Espeli, 52 applications were more thoroughly considered by the Price Directorate, but only a few resulted in exemptions. Thirteen complaints were submitted to the Ministry, all of which were rejected. However, exemptions were granted for books, scrap iron and radios. By 1961, the Price Directorate had received a number of applications concerning horizontal price fixing, about half of which resulted in exemptions. Espeli notes that the large majority of these were granted for short periods (ie less than a year). However, many of these exemptions were later extended for an indefinite period. The exemption policy was more lenient towards the retail sector, while a stricter policy was maintained towards the production and wholesale levels.

By 1961, more detailed price regulation coincided with a more lenient exemption policy, both in relation to vertical and horizontal price fixing. The liberal policy of granting exemptions from vertical and horizontal price fixing in the 1960s reflected the authorities’ predominantly positive view towards economic cooperation between Norwegian undertakings facing increased international competition. Competition policy in Norway in the 1960s was characterised by limited political interest, weak enforcement of the regulatory prohibitions on vertical and horizontal price fixing and a lenient exemption policy. These general trends continued until the 1980s, when effective competition again became an important goal for the Norwegian economic policy.

5. The dynamic impact of the prohibitions on vertical and horizontal price fixing on Norwegian cartel practices

5.1 Introduction

In this section, we take a closer look at how cartel contract types developed over time. In particular, we focus on what happened to cartel contract types after the two legislative changes in 1957 and 1960. We first consider the development in the composition of contract types, and then look into how the cartel contract type composition changed over time. First, by looking at how entering cartels chose their cartel types, then by examining to which extent the continuing cartels changed their contracts, and, finally, by scrutinising the contract types of the cartels leaving the Registry (dying).

5.2 Cartel contract type composition in the cartel population over time

In Table 3, we look at what the composition of cartels looked like over the period 1955 to 1989. The years included are the recording years when the Price Directorate published dedicated reports from the Registry.

| Main cartel types | Price cartel types disaggregated | |||||||

| n | Pure allocation | Mixed price-allocation | Quota | Pure pricing | Fixed price rule | Suggested pricerule | Payment rule | |

| 1955 | 295 | 4 % | 1 % | 9 % | 77 % | 46 % | 26 % | 32 % |

| 1957 | 329 | 5 % | 1 % | 9 % | 76 % | 47 % | 23 % | 31 % |

| 1962 | 378 | 6 % | 4 % | 9 % | 69 % | 41 % | 23 % | 33 % |

| 1967 | 257 | 10 % | 8 % | 14 % | 54 % | 31 % | 24 % | 35 % |

| 1972 | 218 | 11 % | 8 % | 17 % | 52 % | 35 % | 23 % | 40 % |

| 1977 | 187 | 10 % | 8 % | 17 % | 53 % | 43 % | 8 % | 41 % |

| 1983 | 169 | 11 % | 7 % | 15 % | 54 % | 41 % | 4 % | 39 % |

| 1989 | 127 | 13 % | 5 % | 11 % | 60 % | 53 % | 5 % | 25 % |

In terms of composition, there are no large changes in 1962, the first year after the two new legislative changes were in place. The share of pure pricing cartels is reduced from 76% to 69%, and the three other main types obtain a somewhat higher share than before, but the changes are not very large. Even the disaggregated numbers for pricing clauses do not show large changes, but we do see fewer fixed price cartels and a marginal increase in the share of cartels with contract clauses on payment rules. If anything, it seems that the effect of the Regulations took some time to take place since the 1967 numbers are clearly much more suggestive. Then pure pricing cartels only constitute 54% of the cartels having profit maximising contract clauses (as compared to a 76% share in 1957), and the three other clauses have increased their shares significantly. This pattern is also found for the disaggregated fixed price cartel clauses, whose share fell by another ten percentage points from 1962 to 1967. Note that several cartels did not have any of the four main clauses. In 1957, 9% of all cartels had no clauses on profit maximisation, in 1962 this number increased to 12% and in 1967 to 14%, the highest number during the whole registration period.

5.3 Cartel contract type composition among the entering cartels over time

Let us now turn to the entering cartels. Their contract type composition is shown in Table 4.

| Main cartel types | Price cartel types disaggregated | |||||||

| n | Pure allocation | Mixed price-allocation | Quota | Pure pricing | Fixed price rule | Suggested pricerule | Payment rule | |

| 1955 | 295 | 4 % | 1 % | 9 % | 77 % | 46 % | 26 % | 32 % |

| 1957 | 34 | 6 % | 6 % | 9 % | 68 % | 56 % | 3 % | 24 % |

| 1962 | 51 | 15 % | 19 % | 19 % | 43 % | 52 % | 7 % | 50 % |

| 1967 | 36 | 19 % | 5 % | 19 % | 38 % | 30 % | 8 % | 27 % |

| 1972 | 14 | 7 % | 7 % | 47 % | 33 % | 60 % | 60 % | |

| 1977 | 26 | 4 % | 8 % | 12 % | 73 % | 65 % | 12 % | 31 % |

| 1983 | 15 | 6 % | 6 % | 75 % | 50 % | 25 % | ||

| 1989 | 14 | 14 % | 7 % | 71 % | 79 % | 7 % | ||

The legislative changes seem to have had some effect for the entering cartels’ choice of contract types. First, we observe that when compared to 1957, where 68% of the 34 entering cartels were pure pricing cartels, this share is reduced to 43% and 38% in 1962 and 1967, respectively. Furthermore, the three other main types all more than doubled or tripled their share among the entering cartels between 1957 and 1962.

To understand the magnitude of the reduction in pure pricing cartels, let us compare 1957 and 1962. In 1957, 23 of the 34 entering cartels were pure pricing cartels, the same absolute number of pricing cartels entered in 1962, but in the latter year the 23 cartels amounted to only 43% of the total cartels entering (54). Applying the 1957 share on the entering cartels in 1962, we would have seen 36 pure pricing cartels enter in this year – whereas we saw only 23. Thus, we find a significant reduction in the number of pure pricing cartel entries.

From Table 4 we further see that the prohibition on fixed mark-ups and prices led to a change from fixed price entries to more suggested price- and payment rule entries in 1962, as compared to 1957. The latter two contract clauses more than doubled their shares in 1962 (note again that the disaggregated shares are not mutually exclusive and can sum up to more than 100%).

5.4 Changes in cartel contract types among continuing cartels over time

In Table 5 we display the changes in contract types among the cartels that stayed on in the Registry.

When looking at the changes in contract types over time, we observe two distinct patterns. First, we observe surprisingly few changes over time in general – in most of the periods the cartel types do not change at all. Second, to the extent that cartels did change their main clauses on how to maximise profits, most changes took place in 1962 after the two legislative changes were implemented, though the number of changes are rather modest.

| Year | Continuing cartels | Main cartel types | Price cartel types disaggregated | |||||

| Pure allocation | Mixed price-allocation | Quota | Pure pricing | Fixed price rule | Suggested price rule | Payment rule | ||

| 1955 | 295 | |||||||

| 1957 | 327 | -0.3 % | ||||||

| 1962 | 221 | -0.5 % | 1.4 % | -1.4 % | -4.1 % | -10.4 % | 4.5 % | -1.4 % |

| 1967 | 204 | 0.5 % | -0.5 % | -0.5 % | 0.5 % | 3.9 % | ||

| 1972 | 161 | 1.8 % | 3.1 % | |||||

| 1977 | 154 | -8.9 % | ||||||

| 1983 | 113 | -0.9 % | 0.9 % | -1.7 % | ||||

| 1989 | 81 | 1.2 % | ||||||

We do also observe one large negative change in 1977 for cartels agreeing on suggested prices. This change is due to a group of ten grocery retailers that removed their agreement on suggested prices. However, they still kept their agreement on payment rules. The change in 1977 was initiated by their umbrella association changing their rules. Since they still coordinated on payment rules, they keep the status as pure pricing cartels.

Of the relatively large group of 221 continuing cartels in 1962, only 13 cartels (6%) changed their main contract type, nine chose to no longer have pure price contracts, three stopped being quota cartels, and one cartel stopped allocating markets. Out of these 13 cartels, three changed into mixed price and market allocation cartels, but as many as ten removed their pricing clauses and stopped coordinating on any main clause.

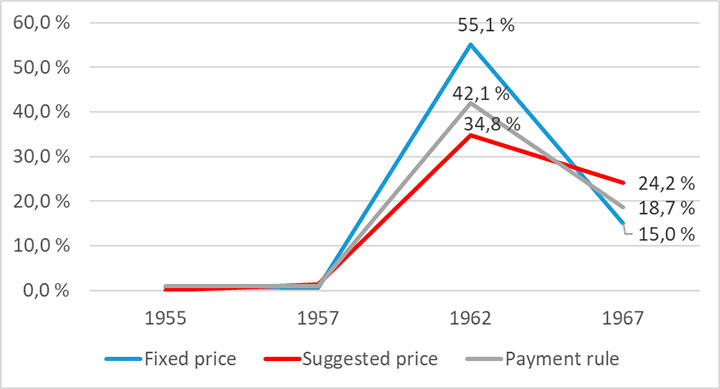

We see even more changes in the usage of disaggregated pricing clauses. Not surprisingly, there is a larger reduction in fixed price clauses, where 23 cartels abandoned such clauses in 1962. To the extent that these changed to other pricing clauses, ten chose to coordinate on suggested prices, which was still legal.

5.5 Cartel contract type composition among the dying cartels

We now turn to cartel deaths. In Table 6 we tabulate death rates both for all cartels and conditioning on contract types.

| Year | Cartel deaths (n) | Cartel deaths (%) | Main cartel types | Price cartel types disaggregated | |||||

| Pure allocation | Mixed price-allocation | Quota | Pure pricing | Fixed price rule | Suggested price rule | Payment rule | |||

| 1955 | |||||||||

| 1957 | 2 | 1 % | 0.8 % | 0.7 % | 1.3 % | 1.0 % | |||

| 1962 | 157 | 42 % | 13.6 % | 17.1 % | 51.5 % | 55.1 % | 34.8 % | 42.1 % | |

| 1967 | 53 | 21 % | 11.5 % | 15.0 % | 17.1 % | 22.9 % | 15.0 % | 24.2 % | 18.7 % |

| 1972 | 57 | 26 % | 25.0 % | 33.3 % | 22.2 % | 28.6 % | 19.5 % | 46.9 % | 21.8 % |

| 1977 | 33 | 18 % | 10.5 % | 14.3 % | 22.6 % | 20.4 % | 20.3 % | 50.0 % | 18.4 % |

| 1983 | 56 | 34 % | 22.2 % | 54.5 % | 44.0 % | 28.6 % | 21.7 % | 14.3 % | 54.5 % |

| 1989 | 46 | 36 % | 43.8 % | 66.7 % | 64.3 % | 25.3 % | 34.8 % | 16.7 % | 41.9 % |

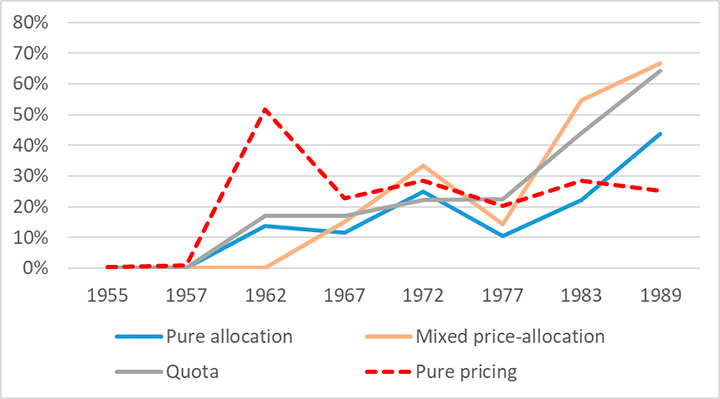

Only two cartels died in 1957, but after the legislative changes in 1960, as many as 157 cartels died – amounting to 42% of the stock of 378 cartels in 1962 (see Table 3). Scrutinising cartel contract types, we find that of those having a pure pricing cartel, more than half of the population dies (52%). The numbers for the three other main contract types are much lower and between 0% and 17%. In fact, 1962 stands out as the year when, in both relative and absolute numbers, most cartels die. This becomes even clearer when we look at fixed price cartels. In 1962, 55% of these die. The death rate for the other reported years for these cartels never exceeds 22%, except for the last year, when 34% of the fixed price cartels died. As compared to 1957 and 1967, also many payment rule (42%) and suggested price cartels died (35%) in 1962.

Turning the shares into absolute numbers, in 1962 there was a stock of 378 cartels (327 that continued from 1957 and 51 new entries, see Tables 3–5). Of these, 262 were pure pricing cartels, as many as 135 of which died in 1962. Only nine cartels died within the three other main contract type groups. This implies that the stock effect in terms of the share of pure pricing cartels is even more pronounced in the 1967 composition figures in Table 3. The number of pure pricing cartels that continued until 1967 is drastically reduced due to the high death rate for these cartels in 1962. This is also exactly what we saw in Table 3: the share of pure pricing cartels in the remaining stock of cartels is down to only 54% in 1967.

In Figure 1 we show the time development of deaths for the major contract type cartels. Clearly, pure pricing cartels stand out in 1962. Except in 1989, the death rates for pure pricing cartels are relatively parallel to those of the other contract types, but in 1962 they are much higher.

Figure 1

Cartel deaths across major contract types 1955 to 1989

In Figure 2 we look at the development for contract types of the disaggregated pricing cartels before and after the legislative changes were implemented. Again, we see this clear pattern. All cartels using pricing contract clauses are leaving the market much more frequently in 1962 than in the rest of the period.

Figure 2

Cartel deaths across disaggregated pricing cartel contract types between 1955 and 1967

5.6 Cartel contract type development summarised

We have analysed the development in cartel contract types. First, we look at the composition of the cartel population over time, and then decompose the aggregated numbers by scrutinising the changes in composition in cartel contracts stemming from the entrants, the continuers and the cartels leaving the market.

Our main focus is how the legislative changes in 1957 and 1960 affect the composition of cartels. Since the changes in particular restricted the scope for collaboration on prices, we expect to observe the largest changes within pricing cartels. Indeed, we do observe that pure pricing cartels are becoming rarer, and, in particular, the share of hardcore fixed price cartels is reduced. However, the changes we observe are smaller than anticipated, solely considering the new restrictiveness imposed by the new Regulations. This might potentially be ascribed to a liberal policy on granting exemptions from the prohibition for several industries (for instance, banking, insurance and newspapers had a long period of exemption from the new legal requirements), but also a liberal policy of granting individual exemptions (see section 4.4 above).

Furthermore, we observe one very clear and distinct pattern: the changes take place through the composition of new entering cartels, and even more so through the exit of pure pricing cartels. Only to a very limited degree do we see cartels change their contracts and continue as the same cartel in a new form. One would think that a well-established cartel that meets new legal requirements on how to cooperate legally would be able to figure out new ways of cooperating, but surprisingly few cartels (at least pricing cartels) did so. In 1962, only nine pure pricing cartels chose to agree on a new form of cooperation, whereas 135 pure pricing cartels left the market. This observation is interesting since it suggests that cartels have a very limited flexibility to change their way of cooperation, even within a framework where they could legally meet and agree on written legal cartel contracts. One might also speculate whether this suggests that coordination on price only to a limited degree can be substituted by the possibility to coordinate sharing of markets and quotas. If these coordination forms were strong substitutes to pricing coordination, we should have seen more contract changes as compared to the high number of cartels dying.

If we condition on being an industry cartel or a service sector cartel, the 1962 death rates do not differ that much, ie 56% and 48% respectively, which suggests that there are no large sectoral differences that can explain why pure pricing cartels rather chose to die than change their way of cooperation. Furthermore, pure pricing cartels are not very different in terms of duration (median = 22) and size (median = 11) compared to the average cartels in our sample (see Table 1). Thus, even though they are marginally more short-lived and somewhat smaller, they have been around for quite a while before choosing to leave the market.

In sum, the Norwegian regulatory changes did have an effect on the (observed) cartel composition in the Registry, but the effect came mostly through a substantial amount of pure pricing cartels leaving the market, rather than these cartels changing their contract types.

6. Concluding comments

Norwegian competition law between 1954 and 1993 was significantly dissimilar from that of today. The Price and Competition Act 1953, which provided the Price Directorate with broad discretionary competences to regulate and intervene, was also distinctly Norwegian and different from the prohibition based competition law regimes for example in the US or the EEC. Both the objectives of the 1953 Act, as well as its regulatory means (control with prices, dividends as well as private competitive restraints), were diverse and broad reaching. However, the Regulations on vertical and horizontal price fixing from 1957 and 1960 set out prohibitions rather than competences for discretionary intervention. The Regulations were limited to restrictions on price competition, and may be contrasted to our contemporary § 10 Competition Act 2004, Article 53 EEA Agreement and Article 101 TFEU, which cover all forms of anti-competitive collusion.

The 1957 and 1960 Regulations were intended to increase competition and further economic efficiency after periods of detailed price regulation during and after the Second World War. Competition policy in the 1960s and 1970s was nevertheless characterized by limited enforcement of the prohibitions, a mostly lenient exemption policy and increasingly frequent price freezes.

Private cartel agreements and (anti)competitive practices were subject to mandatory notification and registration in the Norwegian Cartel Registry over this period. The Price Directorate published entries of notified cartels and restrictions in Pristidende, as well as in ten different volumes from 1955 to 1991. The publications provide empirical data on cartelisation and cartel arrangements under a regulatory regime different from contemporary anti-cartel law and policy.

Overall, Norwegian cartel demography resembles what we see in comparable registries in Finland and Austria, but pricing cartels were much more common in Norway, amounting to two-thirds of the cartels in the population. The second most common cartels were quota cartels, representing one-tenth of the Norwegian legal cartel population. When analysing the dynamic development of contract types, we find that pure pricing cartels were becoming rarer, and, in particular, the share of hardcore fixed price cartels was reduced. However, the changes we observe are smaller than anticipated, particularly solely considering the new restrictiveness imposed by the new laws. This might potentially be ascribed to a liberal policy on granting exemptions from the prohibition for several industries, and also to a liberal policy of granting individual exemptions.

Furthermore, we observe one very clear and distinct pattern: the changes take place through the composition of new entering cartels, and even more so through the exit of pure pricing cartels. Only to a very limited degree do we see cartels change their contracts and continue as the same cartel in a new form. One would expect that well-established cartels that meet new requirements on how to cooperate legally would be able to figure out new ways of cooperating, but surprisingly few cartels did so. In 1962, only nine pure pricing cartels chose to agree on a new form of cooperation rather than pure price, whereas 135 pure pricing cartels left the market. This suggests that (at least pricing) cartels had a very limited flexibility to change their way of cooperation, even within a framework where they could legally meet and agree on legal written cartel contracts. One might also speculate whether this suggests that coordination on price only to a limited degree can be substituted by the possibility to coordinate on sharing markets and quotas. If these coordination forms were strong substitutes to pricing coordination, one should have seen more contract changes as compared to the high number of cartel deaths.

The latter result has a bearing on what to anticipate from modern illegal cartels. In terms of cooperation modes, cartels, and pricing cartels in particular, seem not to be very robust in the sense of flexibility. If the substitutability towards other modes of cooperation such as market sharing or quota cartels is particularly low for pricing cartels, this also suggests that pricing cartels might be both more efficient in raising profits and, as such, even more detrimental to welfare than other cartel types.

This article was made possible through a research grant from the Norwegian Price Regulation Fund in 2017 for the research project ‘Industrial organization of legal and illegal cartels: dynamics in collusion over time and jurisdiction’.

- 1Lov 26. juni 1953 nr 4 om kontroll og regulering av priser, utbytte og konkurranseforhold [Act of 26 June 1953 no 4 on prices, dividends and competition].

- 2Forskrift 18. oktober 1957 nr 8782 om leverandørreguleringer [Regulation of 18 October 1957 no 8782 on supplier restrictions].

- 3Forskrift 1. juli 1960 nr 9153 om konkurransereguleringer av priser og avanser [Regulation of 1 July 1960 no 9153 on competitive restrictions on prices and profits].

- 4Lov 11 juni 1993 nr 65 om konkurranse i ervervsvirksomhet [Act 11 June 1993 no 65 on competition].

- 5Agreement on the European Economic Area, OJ 1994 L 1/ 3 (‘EEA Agreement’).

- 6Lov 27 november 1992 nr 109 om gjennomføring i norsk rett av hoveddelen i avtale om Det europeiske økonomiske samarbeidsområde (EØS) [Act 27 November 1992 no 109 on implementation of the EEA Agreement].

- 7In Norwegian, ‘Konkurransetilsynet’.

- 8Lov 5 mars 2004 nr 12 om konkurranse mellom foretak og kontroll med foretakssammenslutninger [Act 5 March 2004 no 13 on competition].

- 9As well as a prohibition on abuse of market dominance (§ 11), mirroring Article 54 of the EEA Agreement and Article 102 TFEU.

- 10NCA, ‘Konkurransekriminalitet’ Konkurransetilsynet.no (16 March 2018) <http://www.konkurransetilsynet.no/konkurransekriminalitet-en-av-tre-bedriftsledere-mener-det-skjer-ulovlig-samarbeid-i-egen-bransje/>.

- 11The summaries were published in the following years: 1955, 1957, 1962, 1967, 1972, 1977, 1983, 1989, 1990 and 1991.

- 12Ari Hyytinen, Frode Steen and Otto Toivanen, ‘Cartels Uncovered’ (2018) 10(4) American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 190-222; Ari Hyytinen, Frode Steen and Otto Toivanen, ‘An anatomy of cartel contracts’ (2019) 129(621) The Economic Journal 2155–2191.

- 13Nikolaus Fink, Philipp Schmidt-Dengler, Konrad Stahl and Christine Zulehner, ‘Registered Cartels in Austria – Overview and Governance Structure’ (2017) 44(3) European Journal of Law and Economics 385–423.

- 14Susanna Fellmann and Martin Shanahan (eds), Regulating Competition – Cartel Registers in the Twentieth Century World (Routledge 2016) 117 (referring to documented cartel registers in Norway, Denmark, Italy, Sweden, Japan, United Kingdom, Germany, Finland, Netherlands, New Zealand, Austria, Israel, Spain, Australia, India, Pakistan and South Korea).

- 15NCA, ‘Glimt fra prisdirektoratets historie 1917-1992’ Konkurransetilsynet.no (14 May 1992) <http://www./konkurransetilsynet.no/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/glimt_prisdirek_historie.pdf>.

- 16Lov 6 august 1920 om regulering av vareprisene [Act 6 August 1920 on price regulation].

- 17NCA (n 15).

- 18Lov 12 mars 1926 nr 3 om kontroll med konkurranseinnskrenkninger og om prismisbruk (trustloven) [Act 12 March 1926 no 3 on control with competitive restrictions and price abuse].

- 19See Espen Storli and Andreas Nybø, ‘Publish or be damned? Early cartel legislation in USA, Germany and Norway, 1890-1940’ in Fellman and Shanahan (n 14) 17-29.

- 20In Norwegian, ‘Trustkontrollkontoret’.

- 21In Norwegian, ‘Trustkontrollrådet’.

- 22For the first part of that period, see NCA (n 15). For the period 1940-1945, see Harald Espeli, ‘Economic consequences of the German Occupation of Norway 1940-1945’ (2013) 38(4) Scandinavian Journal of History 502-524.

- 23Provisorisk anordning 8. mai 1945 om prisregulering og annen regulering av ervervsmessig virksomhet [Provisional regulation 8 May 1945 on price regulation].

- 24Mellombels lov 30. juni 1947 nr. 12 om prisregulering og anna regulering av næringsverksemd [Temporary act 30 June 1947 no 12 on price regulation].

- 25Harald Espeli, ‘Transparency of cartels and cartel registers – A regulatory innovation from Norway?’ in Fellman and Shanahan (n 14) 150.

- 26Ibid 150.

- 27See n 1.

- 28Lucy Smith, ‘Domstolenes adgang til å sette til side kontraktsvilkår etter prislovens § 18, første ledds annet punktum’ (1982) 151(4) Tidsskrift for rettsvitenskap 755-775.

- 29Espeli (n 25) 150.

- 30Forskrift 19 mars 1954 nr 3590 om registrering av konkurransereguleringer og storbedrifter [Regulation of 19 March no 3590 on registration of competitive regulations and large undertakings].

- 31The EEA Agreement extended the principles of the EU internal market to Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.

- 32See n 6.

- 33See n 4.

- 34See n 8.

- 35Lov 5 mars 2004 nr 11 om gjennomføring og kontroll av EØS-avtalens konkurranseregler mv (EØS-konkurranseloven) [Act 5 March 2004 no 11 on implementation of EEA competition rules].

- 36Harald Espeli, ‘Fra Thagaard til Egil Bakke. Hovedlinjer i norsk konkurransepolitikk 1954-1990’ (1993) SNF-rapport 39/93.

- 37NOU 1991:27 Konkurranse for effektiv ressursbruk.

- 38NCA (n 15).

- 39NOU 1991:27 (n 37) 49.

- 40Espeli (n 36) 9.

- 41See n 30.

- 42Espeli (n 36) 23.

- 43Ibid 10.

- 44NOU 1991:27 (n 37) 51.

- 45Ibid 51.

- 46Espeli (n 36) 10.

- 47Ibid 10.

- 48NOU 1991:27 (n 37) 54.

- 49Ibid 166-167.

- 50Ot.prp.nr.41 (1992-1993), section 6.5.4.

- 51Our dataset does not include registered large undertakings and registered entries prior to 1955.

- 52Some transport central cartels that are only entered in one year are excluded. So are very large cartels (ie, cartels, with more than 100 members) and very old cartels (ie, cartels that more than 100 years old) – the former because these large cartels were more like associations that shared common price lists and could include thousands of members, while the latter consist of cartels such as guilds over 200 years old in trades such as shoemaking. Finally, any new cartels arriving after 1989 (only one) are left out since the last two summaries from 1990 and 1991 came at a time when the political discussion on abandoning cartels very likely affected the registration.

- 53See Ari Hyytinen, Frode Steen and Otto Toivanen, ‘Cartels Contracts and Organization: A Coding Manual’ (Aalto University 2007; last version 25 November 2016).

- 54The coding of the Norwegian cartel contracts has been done over a period of several years, and is partly financed by the international research project ‘Strengthening Efficiency and Competitiveness in the European Knowledge Economies’ (SEEK) at ZEW, ‘What Do Legal Cartels Tell Us About Illegal Ones?’ 2013-2015, and the Norwegian research project ‘Legal Cartels’ financed by the Norwegian Competition Authority, 2017-2019.

- 55One such example is the National association of soda producers, a cartel that was founded in 1913, and which explicitly writes that their members no longer cooperate on prices, but do cooperate on minimum delivering volumes of soda in boxes (Reg No 1.26, 1957 registry, 52).

- 56Hyytinen, Steen and Toivanen, ‘An anatomy of cartel contracts’ (n 12).

- 57Ibid.

- 58Margaret C Levenstein and Valerie Y Suslow, ‘What determines cartel success?’ (2006) XLIV Journal of Economic Literature 43-95.

- 59Payment rules were often used in addition to price clauses or sometimes alone, stating rules on discounts or rebates.

- 60See n 2.

- 61Pristidende 1957 536.

- 62Joined Cases 56 and 58/64, Consten and Grundig v Commission, judgment of 13 July 1966 (ECLI:EU:C:1966:41).

- 63Article 4 of Commission Regulation (EU) No 330/2010 of 20 April 2010 on the application of Article 101(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to categories of vertical agreements and concerted practices [2010] OJ L 102/1.

- 64See n 3.

- 65Pristidende 1960 420.

- 66Ibid 425.

- 67Case C-382/12 P, MasterCard v Commission, judgment of 11 September 2014 (ECLI:EU:C:2014:2201) para 76.

- 68Pristidende 1957 531.

- 69Espeli (n 36) 26.

- 70Ibid 48.

- 71Pristidende 1957 548 and Pristidende 1960 448.

- 72Ibid 31.

- 73Ibid.

- 74Ibid 61.

- 75Ibid 62.

- 76NOU 1991:27 (n 37) 51.

- 77Espeli (n 36) 10.

- 78Note that changes taking place in between these dedicated reports are also coded using the entries in Pristidende, and accounted for and aggregated into the numbers we present here.

- 79See n 55.

- 80A cartel that is an entrant is defined as a cartel that did not exist in the years prior to the year in which the Price directorate published a dedicated report from the registry, but was observed in the report this year.

- 81The continuing cartels are those that already were in the registry plus those that entered that year.

- 82See the registry 1977, p 51-54, in particular on register number 1.541: The association for grocery retailers (‘Norges Kolonial- og Landhandlerforbund (NKLF) Oslo’).

- 83See the example in n 55.

- 84Note that when a cartel changed from eg a fixed pricing clause to a payment rule clause, they did not change their status as a pure pricing cartel. Thus, we see more changes on this disaggregated level, than we observe on the more aggregated pure pricing clause level.

- 85Note that we here assume that cartels that we do not observe in the registry, have left the market. This might of course not be the case, even in a jurisdiction like Norway, where cartels were legal. In particular, cartel types no longer legal in the registry, might of course reappear in the market as illegal non-registered cartels.