Hate Speech and Racialised Discrimination of the Norwegian Sámi: Legal Responses and Responsibility

Associate Professor, Faculty of Social Studies, VID Specialised University

Publisert 16.12.2021, Oslo Law Review 2021/2, side 88-107

This article discusses the racialised discrimination of the Sámi people and how the Norwegian judiciary deals with it. It draws historical lines to social Darwinism as practised in Norway, where comparisons of the Sámi’s physical characteristics to the Norwegian majority population were commonplace. The official Norwegian position was that the Sámi were not an indigenous people and therefore lacked inalienable rights. The racialised understanding of the Sámi as an untrustworthy and lazy people of the past, reverberates in today’s hate speech that builds on similar stereotypes. Norway has come a long way since racial hygiene was a mainstream scientific approach. Yet, still today, the Sámi are statistically overrepresented with experiences of discrimination. This article examines the legal responses and responsibility of Norway to tackle hate speech and discriminatory utterances that manifest a racial understanding of Norway’s indigenous people. In the discussion, special emphasis is placed on Norway’s international treaty obligations.

Keywords

- Sámi

- indigenous people

- hate speech

- racial discrimination

- group stereotypes

- minority protection

1. Introduction

‘Hello, they belong on the vidda [highland/plateau], not here with their ridiculous clown costumes they are marching around in. If you smell lighter fluid, a Sámi is not far away, with his 1.30 meters and his smell of fire’.

In February 2019, the Norwegian district court in Salten convicted a 50-year-old man for degrading, offensive, and harassing statements, including those cited above. He was sentenced under section 185 of Norway’s Penal Code to 18 days of conditional prison and a fine of 15,000 kroner. It was the first ever judgment that dealt with hate speech against the Sámi indigenous people. The accused claimed he did not have a hateful or discriminatory motive but intended to be funny. The district court quashed this claim. The man appealed the judgment to the Hålogaland Court of Appeal where his defence lawyer asserted that, in Northern Norway, it is common to harass the Sámi in humorous contexts, without legal consequences. The Court of Appeal upheld the district court’s assessment of the case.

The case finds its origin in a newspaper article by Avisa Nordland of 2 August 2018 on tame reindeer that graze along the roadway and thereby create dangerous traffic situations in Finnmark, the northernmost county of Norway at the time. Reindeer husbandry is one of the traditional occupations of the Sámi and an important element of their culture and heritage. On the same day, the newspaper linked the article to its Facebook page, which has approximately 30,000 followers. The 50-year-old man wrote his comments on the Facebook page of Avisa Nordland, whereupon a private person reported them to the police.

Negative stereotypes and prejudice of the Sámi are alive and well, as the introductory statement of the convicted man intimates. References to the bodily odour or the height of the Sámi as exemplified in the statement, are influenced by race science of the past century. Drawing on established historical research, this article considers how social Darwinism and the assimilation policy of Norway contributed to creating a racialised image of the Sámi indigenous people in Norway that reverberates in contemporary hate speech, a crime punishable under Norwegian penal law.

From 1851 onwards, language and culture assimilation was at the core of the Norwegian State’s plan for the Sámi, and domestic legislation was an important tool in its implementation. The Education Act stipulated that all teaching should be in Norwegian only, thus forcing Sámi children to abolish their native languages and part of their identity. This article discusses how the international legal framework can assist in the revitalisation of the indigenous languages and how the different instruments interrelate, including differences between minority and indigenous rights.

Taking into consideration Norway’s obligations under international human rights law, the article then examines how its judiciary tackles prejudice, stereotypes, and hate speech of the Sámi based on racialised understandings. The article analyses the Salten case under the aegis of the right to freedom of expression and, inter alia, the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), taking account of the narrower margin of appreciation that states are accorded in cases dealing with vulnerable groups. Given the relative paucity of legal discussions of the discrimination of the Norwegian indigenous people, the article also aims at making the issue more accessible to non-Norwegian scholars and the public at large. Finally, the article presents possible ways forward, including how the Norwegian Truth and Reconciliation Commission might contribute to countering racialised hate speech directed at the Sámi.

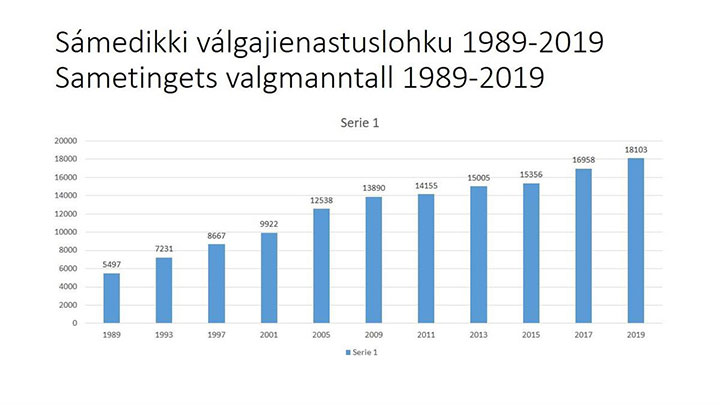

2. The Sámi in Norway

The Sámi are an indigenous people who have their traditional settlement areas in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. The Sámi live scattered across all four countries, with the largest percentage in Norway. Except for Russia, there are no official registrations of who has a Sámi identity. It is estimated that around 50-65,000 Sámi live in Norway, that is between 0.93 and 1.21% of the total Norwegian population of 5.4 million. Although it is unknown exactly how many Sámi live in Norway, the registrations in the Sámi regional Parliament’s electoral roll give an indication of the numbers. Since its inception, the electoral roll has steadily increased: from initially 5,497 persons in 1983 to 13,890 in 2009, to 18,103 in 2019.

Figure 1

Sami parliament’s electoral roll 1989-20197

This marked increase is not caused by an increase of the Sámi population in terms of birth rates. It is likely due to the regional parliament having firmly established its position regarding its constituency and its role vis-à-vis the national parliament in Oslo. One might speculate that the increase in the electoral roll reflects the growth in self-identification, consciousness, and pride of Sami heritage.

3. Social Darwinism and Norwegianisation policy

3.1 Social Darwinism and anthropological studies of ‘Lapps’

Throughout history, indigenous communities have been exposed to undignified and dehumanising research from which they could not benefit. For many decades, Norway and Sweden were especially involved in suppressing the rights of the Sámi, entailing a (partial) loss of their identity. Like other minority and indigenous groups, the Sámi became victims of social Darwinism. The latter originates in the ideas of Charles Darwin, who in his book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection reasoned that the evolution of species was driven by the struggle for survival and natural selection, whereby only the best adapted variations within a species were passed on to the next generation. Based on the laws of nature that prescribe the supremacy of the stronger and healthier over the weaker, social Darwinism offered the ‘survival of the fittest’ as a school of thought. The theory revealed its ugly face once it was applied to members of different human groups, as for instance in Hitler’s understanding of the Jews as a subhuman race. From the late 1800s until the Second World War, social Darwinism was firmly rooted in European public discourse and a scientifically accepted and researched theory.

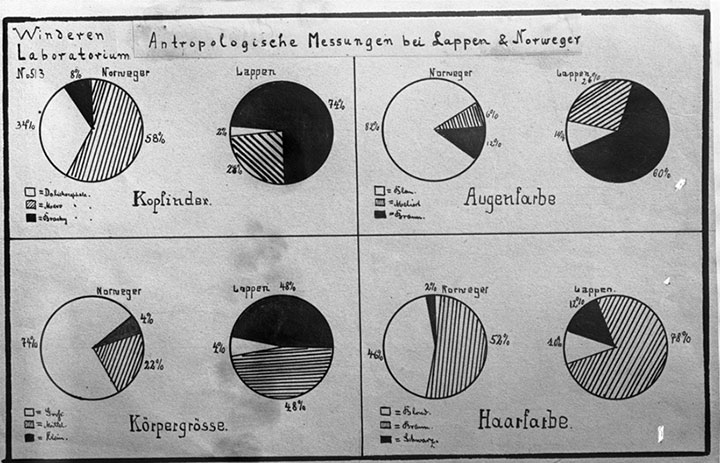

Social Darwinism informed racial hygiene policies, an international scientific movement that grew out of an aim of promoting superior genetic traits. In the years before and after the First World War, Norwegians were at the forefront of racial hygiene thinking, which influenced their perception and treatment of the Sámi. Jon Alfred Mjøen (1860-1939), albeit domestically criticised as being too extreme, was one of the leading physical anthropologists and racial hygienists in Norway. He took numerous physical anthropological measurements of Norwegians and the indigenous Sámi people, then called Lapps, the results of which helped explain the ostensibly inferior and negative traits of the Sámi.

Figure 2

Winderen Laboratorium:

Antropologische Messungen bei Lappen und Norweger

[Anthropological measurements of Lapps and Norwegians], unknown year.

Clockwise from top right: eye colour, hair colour, body size, head index.

Courtesy Kristiania Arbeiderakademi / Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology.

Mjøen conducted his research at the same time as political debates about the Sámi’s rights in the Norwegian society were taking place. The official Norwegian position then was that the Sámi was not an indigenous people of the North and therefore did not have inalienable rights. The authorities tried to halt public utterances to the contrary. Such debates were not uncommon at the time. In 1919, a Swedish scientist held: ‘The Lappish race can hardly be counted among the higher. On the contrary, it is rather a backward development of mankind’. The Norwegian physician and physical anthropologist Halfdan Bryn (1864–1933) even suggested creating the best possible conditions for the Sámi to be able to continue their nomadic life, which would lead ‘this little valuable race element to die a natural death’. Common to these understandings was the idea that the Sámi were incapable of civilisation and culture and therefore could not partake in the nation building of the Norwegian State, which was defined as one State, one people, and one language.

The Sámi became the object of racialised research of ‘primitive’ cultures with presumed biologically inherited traits. Due to their ostensibly low developmental stage, they were placed by scientists on a lower racial hierarchy than the majority population. This inferior position legitimised offensive political and scientific approaches. Scientists concluded that the Sámi were small and weak of growth, childish and sometimes childlike of mind, old-fashioned, degenerated, and pagan, thereby contributing to the labelling of Sámi as inferior to Norwegians. Such racialised understanding resurfaces in the statement of the convicted in the Salten case, playing on stereotypes of the Sámi as nomadic herders (‘they belong on the vidda’) of short stature (‘with their 1.30 meter’).

3.2 Norwegianisation policy: stereotypes and language issues

Psychiatric patient journals of 1902-1940 reveal a perception of Sámi inferiority and a paternalistic attitude of the authorities. Stereotypical perceptions were dominant, describing the Sámi as mentally and physically less well-equipped, more inclined to alcoholism and mental illness. In journals, Sámi and their family members were described with morally loaded terms as ‘vicious’, ‘foolish’, ‘infantile’, and ‘very simple’, thereby reverberating ideas of social Darwinism. Language problems between doctors and patients were omnipresent. One journal note reads: ‘Since he only speaks Lappish, there is no information to be obtained from him’. Furthermore, ‘[i]f someone talks to him, he smiles emptily and stereotypically and mumbles something in Lappish’. Language issues complicated the communication between doctors and patients, but their relationship was also negatively influenced by group stereotypes of the indigenous people as being of lesser sophistication, finesse, and value.

Language and culture assimilation was at the core of the Norwegian State’s plan then for the Sámi. State efforts to assimilate the indigenous people began already in the early 18th century, yet from 1851 onwards, the Norwegian State implemented an official Norwegianisation policy. The policy was built upon an understanding that ‘the only salvation for the Lapps is to be absorbed by the Norwegian nation’, as the later-to-be first prime minister of Norway, Johan Sverdrup, declared from the rostrum of the Storting, the Norwegian Parliament. Social Darwinism, in combination with a newly developed sense of nationalism, provided an ideological legitimacy to the claim that the Sámi, as an intellectually and culturally inferior race with bad genes, were doomed by the laws of evolution.

In addition to political and social attitudes towards the Sámi, Norwegian legislation played a key role in implementing and consolidating the Norwegianisation policy. Based on the prevailing historical, legal, and political views of the time—and similar to developments in various colonies around the world—the Sámi legal traditions were considered non-existent. Of primary importance was the Education Act, which remained in force until 1959, stipulating that all teaching should take place in Norwegian, and teachers who were the most successful in implementing Norwegian were given monetary rewards. It has even been asserted that schools were the battlefield and teachers the frontline soldiers of the assimilation policy.

Thus, the most far-reaching consequences of forced linguistic and cultural assimilation after 1900 occurred in the schools. The authorities used boarding schools as an instrument for the assimilation to ‘promote knowledge of the Norwegian language among the foreign nationalities’, including the Sámi. In these schools, a deepfelt shame and humiliation of the Sámi origin, language, and heritage were instilled, resulting in trauma for the children and the partial disappearance of the native languages from the indigenous areas. Language is an essential element of any peoples’ group identity. The forceful abolition of the Sámi languages led to a partial loss of their cultural identity. The next section examines the revitalisation of the indigenous languages as stipulated in the international legal framework.

4. Revitalization of Sámi language and culture: the legal framework

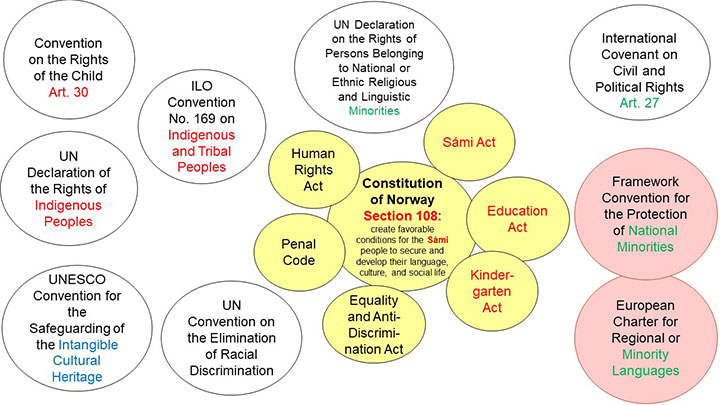

Since the second half of the 20th century, there has been a revitalization of Sámi culture, identity, and language. The obligations of the Norwegian State to create favourable conditions for the Sámi people to secure and develop their language, culture, and social life follows from Section 108 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway. The current government policy is the full recognition of the Sámi languages, culture, and social life, which are considered an enrichment for Norway.

The development of Sámi language rights as stipulated in the Sámi Act, the right to education in accordance with the Education Act, as well as Sámi media and literature have contributed to foremost Northern Sámi gaining a stronger position in society. Nonetheless, all Sámi languages are endangered or red-listed by UNESCO, and their use as everyday language remains in decline, especially in areas where they have been exposed to strong pressure from the majority society.

The international legal framework for minority protection stipulates the right to use minority languages. Minority and indigenous rights are notably not the same: minority rights are individual rights of persons belonging to minorities, while indigenous rights are collective rights of peoples. Minority rights typically aim at ensuring a space for pluralism in a society. Indigenous rights, on the other hand, place the emphasis on effective participation in a larger society and allocate authority for indigenous peoples to make their own decisions. The Sámi are an indigenous people as well as a minority in Norway; they can therefore invoke minority rights in addition to indigenous rights. The following paragraphs sketch the eight most important legal instruments in respect of the use of minorities’ languages.

First, Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is the most widely accepted legally binding provision on minorities. It reads:

In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practise their own religion, or to use their own language.

The treaty provision obliges all States Parties to protect the right of minorities to enjoy and practice their culture and language. Notably, it does not provide special protection to indigenous peoples. Since indigenous peoples are essentially always minority populations, they fall under the protection of Article 27 ICCPR. This has also been the conclusion of the Norwegian Supreme Court, which as recently as October 2021 unanimously ruled that the construction of wind farms in the traditional reindeer grazing areas violated the Sámi’s protected cultural practice under Article 27 ICCPR. In doing so, it confirmed the subsumption of the Sámi under the minority framework protection of Article 27 ICCPR. Moreover, Articles 11-13 and 31 of the UN Declaration on Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) interpret how Article 27 ICCPR applies to indigenous peoples’ cultural heritage, leading to a cross-fertilisation of standards contained in different bodies of international human rights law. It is important to point out that indigenous peoples never considered themselves as minorities in a technical sense of international law, since such status would not do their specific needs justice. However, this view has not hindered the UN Human Rights Committee in making use of Article 27 ICCPR for basic protection of indigenous peoples’ rights.

In the Concluding Observations on Norway’s fulfilment of its obligations under the ICCPR, the Human Rights Committee noted with appreciation the adoption of section 185 of Norway’s Penal Code on hate speech, the provision under which the Salten case was prosecuted. Section 185 defines hate speech as a discriminatory or hate speech that is meant to threaten or insult someone, or to promote hatred, persecution of or the contempt for another person based on his or her

-

skin colour or national or ethnic origin,

-

religion or belief,

-

sexual orientation,

-

gender identity or gender expression, or

-

disability.47. Lov om straff (straffeloven) 20 mai 2005 nr 28.

Despite the adoption of this provision, the Committee remained

concerned about the persistence of hate crimes and hate speech, including on the Internet, against Romani people/Tater, Roma, migrants, Muslims, Jews and Sami persons. The Committee is concerned at the lack of systematic registration of cases and collection of comprehensive data on hate crimes and hate speech. It is also concerned at underreporting of hate crimes and criminal hate speech and at the low rates of convictions for lack of evidence.

The Committee recommended increased reporting and investigation of (online) hate crimes and criminal hate speech, through inter alia strengthening the capacity of law enforcement officials. It also advised in favour of systematic investigation, prosecution, and punishment of perpetrators and the award of appropriate compensation to the victims.

The second instrument is the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Its Article 30 contains a wording and legal standard that are nearly identical to Article 27 ICCPR. By virtue of Article 3 of the Norwegian Act on Human Rights, the ICCPPR and CRC take precedence over other conflicting legislative provisions in Norwegian law, thus strengthening human rights protection on the domestic level. Article 30 CRC extends its legal protection to children of indigenous origin, a fact of relevance to the Sámi of Norway:

In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities or persons of indigenous origin exist, a child belonging to such a minority or who is indigenous shall not be denied the right, in community with other members of his or her group, to enjoy his or her own culture, to profess and practise his or her own religion, or to use his or her own language.

Article 27 ICCPR and Article 30 CRC provide the basis and inspiration for the third instrument, the (non-binding) Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic Religious and Linguistic Minorities, which was adopted under the auspices of the UN in 1992. Norway is a State Party to ICCPR and CRC and member of the UN. Therefore, it has a legal obligation to protect minority rights effectively, including the right to use freely the minority language without discrimination (Articles 1 and 2(1)). The right of persons belonging to national minorities to maintain their identity by means of acquiring a proper knowledge of their mother tongue during the educational process, is equally recognised in Article 1 of the OECD Hague Recommendations regarding the Education Rights of National Minorities of 1996.

The fourth and fifth instruments have been created under the auspices of the Council of Europe. The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages together with the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities constitute the Council’s commitment to the protection of national minorities. The Framework Convention is the first legally binding multilateral instrument devoted to the protection of national minorities worldwide. However, it does not define ‘national minority’, nor is there a general definition of the concept agreed upon by all Council of Europe Member States. Within its margin of appreciation, the Norwegian government interprets ‘national minorities’ as ‘groups with a long connection to Norway’, meaning Jews, Kvens/Norwegian Finns, Romans, Romani people/Tatars, and forest Finns, thus excluding the Sámi as indigenous people. Arguably, the Sámi have the longest connection to Norway and, in accordance with Article 3 of the Framework Convention, they can self-identify as a national minority, thereby falling under the protection of the Convention. One might argue that the compartmentalisation of minorities into indigenous peoples, national minorities, and immigrants weakens their legal protection against discrimination and racism.

The sixth key instrument is the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. It is the only international treaty open for ratification that deals exclusively with the rights of these peoples, taking a cross-cutting approach that includes gender equality and non-discrimination. The Convention is based on respect for the cultures and ways of life of indigenous and tribal peoples and aims at overcoming discriminatory practices affecting these peoples and enabling them to participate in decision-making that affects their lives. While the Convention is considered progressive in surpassing traditional guarantees on non-discrimination, it remains cautious in articulating how the guarantees to protect the identity and culture of indigenous peoples should be operationalised. Norway was the first country to ratify the treaty in 1990.

In addition to the ILO Convention, the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is of great importance. It ‘marks a watershed in state practice as well as in opinio juris’. Although non-binding, it progressively recognises indigenous rights oriented towards preserving the specific identity and culture of indigenous peoples, eg the right to revitalise languages, traditions, and customs (Articles 11 and 13). Article 1 emphasises the enjoyment of human rights of indigenous peoples, as individual and collective rights, thereby broadening their usual scope beyond the individual. Article 8(1) expressly recognises the right not to be subjected to forced assimilation, a right born out of historic wrongs committed against many indigenous peoples, including the Sámi. The Declaration, which places a strong emphasis on collective rights of indigenous peoples to preserve their group identity, constitutes a paradigmatic shift in international law on the rights of indigenous peoples, transforming them from mere objects of international rules into key actors in the international legal process.

Lastly, although not specifically aimed at protecting minority groups only, the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage is the first multilateral binding treaty of its kind that recognises in Article 2(1) that intangible cultural heritage is transmitted from generation to generation and is constantly recreated in response to the environment, nature, and history. The cultural heritage provides communities and groups with a sense of identity and continuity and thereby promotes respect for cultural diversity and human creativity. Article 2(2)(a) of the Convention stipulates that language is a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage. Although the Convention gives its States Parties leeway as to the choice of methods of implementation, it nonetheless requires that they take the necessary measures to ensure the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage. As State Party to the Convention, Norway must ensure the safeguarding of the Sámi languages and heritage. Known threats to cultural heritage include intolerance, disrespect, mass media, and loss of ancestral languages—all directly relevant to Norway and the Salten case.

Following a historic overview of social Darwinism and the official assimilation policy of the Sámi, this section discussed how national and international law tries to equalise past injustice. It examined the eight most important legal instruments on minority language rights, their implementation in national law, and their relationship and relevance for indigenous peoples in general and the Sámi in particular. These factors are summed up in the following figure.

Figure 3

overview of the most important legal tools for the protection of the Norwegian Sámi

(Yellow shading: Norwegian domestic law; pink shading: Council of Europe law; white shading: UN and UN organizations’ law. Red text: specific provisions on indigenous people; green text: specific provisions on minorities; blue text: specific provisions on cultural heritage)

5. The role of courts in dealing with hate speech against Sámi

Until a few decades ago, being a member of the Sámi indigenous people was associated with shame, and the traditional languages or outfits of the Sámi were not used outside of the Sámi society. After the abolishment of the Norwegianisation policy, the situation gradually improved. Yet, still today, many individuals are unduly discriminated against due to their indigenous heritage. Misconceptions, racist and stereotypical depictions are commonplace in the public debate, especially in matters of indigeneity and territorial rights. Condescending and derogatory comments on websites and elsewhere are frequently made, as the Salten case demonstrates. The claim of the accused’s defence attorney in the Salten case that harassments of the Sámi in a humorous context are common in Northern Norway and did not entail legal consequences is in itself disturbing. It reveals that, in parts of the Norwegian population, negative prejudices and stereotypes against the Sámi have been normalised. Rather than questioning and counteracting these discriminatory attitudes, the lawyer attempted to use them in favour of his client. In its judgment, the Court of Appeal put an end to the legitimacy of such an understanding. In discussing the disputed comments of the accused, the Court pointed out that they helped ‘to nurture prejudices that the Sámi have been faced with for decades’. Furthermore, the statements were a ‘qualified offense and involved a gross denigration of the Sámi as an ethnic minority’. In doing so, the Court recognised the continued historical wrong that the Norwegian indigenous people endure. It also acknowledged that, if unchallenged, such prejudices sustain the ostensibly inferior position of the Sámi people.

The Court’s judgment is unambiguous and, although only valid for the particular case before it, contains a clear message: degrading treatment of the Sámi will not be tolerated. The role of the judiciary in this regard cannot be overestimated: it helps to ‘call out’ harmful stereotypes and thereby make visible socially deeply ingrained attitudes that are commonplace. Yet, the naming of a stigma—a deeply discrediting attribute that conveys devalued stereotypes—before a Court is not only positive: the Sámi victims are presented with a pre-assigned label as minority and/or indigenous, hence a position outside the majority population. In inhabiting and objecting a stigma, they acquire a visibility that might not always be welcomed.

It is common that perpetrators of hate speech assert the protection of the right to freedom of expression, as stipulated in section 100 of the Norwegian Constitution and numerous human rights treaties. Then, the courts must perform an interpretative balancing act between that right and the right to non-discrimination. It is claimed that Norway, compared to other European countries, provides for a large degree of freedom of expression. However, when utterances involve the serious degradation of a group’s human dignity, they lose protection. Moreover, the margin of appreciation in dealing with hate speech is restricted by the State obligation to eliminate racial discrimination and to make punishable dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred. The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination concluded that the principle of freedom of speech is afforded a lower level of protection in cases of racist and hate speech and that the prohibition of all ideas based on racial superiority or hatred is compatible with the right to freedom of opinion and expression.

Regarding the margin of appreciation, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has determined:

if a restriction on fundamental rights applies to a particularly vulnerable group in society, who have suffered considerable discrimination in the past […], then the State’s margin of appreciation is substantially narrower […]. The reason for this approach […] is that such groups were historically subject to prejudice with lasting consequences, resulting in their social exclusion.

As section 3 of this article has described, the Sámi historically suffered considerable discrimination and were subject to prejudice with lasting consequences. Arguably, due to their minority status, they are a particularly vulnerable group that has been exposed to social exclusion. It is therefore justified to set the margin of appreciation regarding the freedom of opinion and expression significantly lower.

The Salten and Hålogoland courts established that severe hate crimes against indigenous people entail legal consequences. Had they reached the conclusion that the freedom of expression of the accused outweighed the rights of the victim—the entire Sámi people—not to be exposed to discriminatory utterances, they would have acquiesced to a misculture. The conviction shows that the Norwegian judiciary takes these crimes seriously and no impunity is granted.

In setting a clear precedent, the courts also contribute to fulfilling Norway’s obligations under Article 27 ICCPR and counteract the concerns of the Human Rights Committee mentioned above. Although the Norwegian courts have dealt with numerous cases of hate speech and discrimination of other minority populations, including Muslims and people of colour, the prosecutorial passivity with regard to the Sámi people is remarkable. The Salten case of 2019 was the first time that the Norwegian courts dealt with racial discrimination of the Sámi. Here, the concern of the Human Rights Committee should be recalled that hate crimes and criminal hate speech are underreported and rarely convicted. The Committee recommended Norway to strengthen its investigation capacity on hate crimes and hate speech, and ensure the systematic investigation, prosecution, and punishment of the crimes. In addition to deploying more police officers, prosecutors, and judges, a strategy should involve training authorities in recognising racialised discrimination and hate speech and increase the percentage of Sámi in these functions.

The question could be raised whether the threshold to investigate hate crimes against indigenous peoples is too high. The private person who took legal action against the author of the Facebook comment in the Salten case reported 19 other cases of incitement to hatred against Sámi, none of which were prosecuted. Yet, the judgment against the 50-year-old man might well have been the much-required prosecutorial and judicial push: only one year later, a woman reported another person for a hateful comment, also this one made publicly to a Facebook group. The author of the comment compared the Sámi to the pest, a term that, in the view of the public prosecutor, contained a degrading view of the victim group. The case did not reach the court because the man accepted a fine of 13,000 kroner (approximately 1,200 Euro). In the spring of 2021, another case of hate speech against the Sámi ended with a verdict: a man was convicted for the threatening and derogatory statement ‘bundle them five and five and throw them in the ocean’. These cases show that in the past two years, hate speech against the Sámi is more often prosecuted, degrading and derogatory statements punished, and the judiciary is doing its part in counteracting stigma, prejudice, and racialised perceptions of the Norwegian indigenous people.

A conviction for hate speech requires that the perpetrator must have acted intentionally or grossly negligently and that the statement was public, meaning suitable to reach a larger number of people. The latter requirement was fulfilled in the Salten case because the Facebook group had 30,000 followers. Moreover, the district court judgment concluded that the Sámi were a protected ethnic group according to section 185 second paragraph litera a of the Penal Code. In the trial before the Court of Appeals, the defendant agreed with this conclusion. There seems to be an accepted understanding that section 185 of the Penal Code protects groups, although group membership is not an explicit part of the crime’s actus reus, since the provision protects individuals from hate speech based on skin colour or national or ethnic origin. The interpretation of the provision as protecting a group appears to be settled.

6. Countering the discrimination of the Sámi in Norway

The Sámi are recognised as an indigenous people with a strong legal standing in Norway, including the right to cultural preservation, own territory, and internal self-determination. Their legal protection as indigenous people, however, has not in itself prevented the occurrence of discrimination. Rather, studies have shown that Sámi suffer from cumulative discrimination, based on their historic experience with institutional discrimination and abuse, affecting their health, education, labour market participation, and other aspects of participation and inclusion.

According to a report by the Norwegian National Institution for Human Rights from 2018, Sámi people have a greater risk of being exposed to violence than the non-Sámi population: 40 percent of Sámi men have experienced violence as opposed to 23 percent of non-Sámi men. The report concludes that the ‘figures indicate that Sami ethnicity is a risk factor for being exposed to violence’. This finding accords with international studies that indicate a higher prevalence of interpersonal violence in indigenous populations than in non-indigenous populations.

An example of such violence is the unprovoked violent assault in 2019 on a young student wearing a gákti, the traditional Sámi outfit, in the city centre of Tromsø. The perpetrator stated that he felt like beating a Sámi. The assault, while investigated, was never criminally prosecuted, a decision that led to protests in other cities, in solidarity with the victim and the Sámi cause. The Norwegian historian Bård A Berg believes that joking and everyday racism against the Sámi is commonplace in Northern Norway: the Sámi are portrayed as less intelligent, drunkards, speaking poor Norwegian, and employed in lower paid jobs. He also points out that social media make it easier to spread nasty comments, often under the guise of of the right to freedom of speech. This understanding reveals stereotypes about the Sámi not unlike those in the psychiatric journals discussed above. Group stereotypes of the Sámi are a major concern for the UN Human Rights Committee, which in its 2018 Concluding Observations urged Norway as State Party to the ICCPR to ‘step up its efforts to combat stereotypical and discriminatory attitudes and discriminatory practices towards Sami individuals and the Sami peoples’.

Another incident occurred in the summer of 2020, when a young 20-year-old woman was on her way home by bus in Tromsø. There, she met two acquaintances with whom she exchanged a few words in Sámi. Upon getting off the bus, an elderly passenger allegedly told her: ‘Sámi do not belong anywhere, and certainly not on the bus, where everyone can hear the language’. Especially Sámi residents of Tromsø recount similar experiences: they confirm exposure to Sámi jokes and nonsense joik, two women suffered sexual harassment because they were wearing the gákti, and Sámi children are evidently beaten up by other children who want to prove that Sámi children ‘do not tolerate anything’. Jokes and ridiculing at the expense of minorities often confirm real prejudices against them and are attacks on the Sámi identity. In the worst case, such derogatory statements can be an attack on human dignity, a fundamental right and one of the most pervasive concepts in international human rights law. Degrading, racist, and discriminatory statements deny the Sámi their dignity and liberty and constitute an attack on their fundamental human rights.

Given the fact that a staggering 35 percent of the Sámi-speaking Sámi report discrimination—compared to 3.5 percent of the Norwegian majority population—the Norwegian State appears not (yet) to have been successful in its fulfilment of international legal obligations to prevent discrimination of the indigenous people. Norway is State Party to ICERD, which in Article 1(1) defines ‘racial discrimination’ broadly as

any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.

This definition includes the Sámi indigenous people whose members are exposed to impaired enjoyment of their human rights based on their race, national or ethnic origin, depending on which aspect of their ‘otherness’ is highlighted.

One step to countering racial discrimination effectively, is an increased State effort to tackle hate criminality, including hate speech. The Norwegian government included 10 million kroner (approximately 950,000 Euros) in the State budget of 2021 for this effort. The Minister of Justice at the time acknowledged the seriousness of hate crimes for those directly or indirectly affected, because they create a fear in a group of the population.

Norway is not alone in struggling with issues of hate crime. Research shows that in the EU, despite the Member States’ efforts to combat discrimination, intolerance, and hate crime, the situation is not improving: a large survey found that one in four respondents from minority or immigrant groups had been a victim of racially motivated crime. A main challenge to combating hate crime is the lack of evidence of the perpetrator’s motivation: the EU and the ECtHR both concluded that countries must clearly document the motivation behind racist crimes. According to the jurisprudence of the ECtHR, overlooking the bias motivation behind a crime could amount to violation of the right to protection from discrimination under Article 14 ECHR. In Identoba and Others, the Court held:

without such a strict approach on the part of the law-enforcement authorities, prejudice-motivated crimes would unavoidably be treated on an equal footing with ordinary cases without such overtones, and the resultant indifference would be tantamount to official acquiescence or even connivance in hate crimes.

The Court’s emphasis on the bias motivation is important because perpetrators of hate crimes victimise individuals for (perceived) characteristics that reveal an understanding of the victim as not an individual with his/her own personality, abilities, and experience, but as a non-descript member of a group whom the perpetrator identifies to be of a lesser value. Drawing on this jurisprudence, the EU therefore recommends making hate crimes more visible and increasing their accountability: legislators should aim at enhanced penalties for hate crimes and courts should address bias motivations publicly so as to raise awareness and quell hopes of impunity. These recommendations resonate the concern of the UN Human Rights Committee that encouraged increased identification, registration, and reporting of hate crimes. Only when the source of discrimination can be identified, in our case racism, is it possible to rectify them by legal action.

The next section examines whether the hate crimes committed against the Sámi can be qualified as discrimination on racial grounds. The discussion problematises how law deals with (false) understandings of race and racial identities.

7. Discrimination on racial grounds

Pursuant to the then contemporary scientific method of racial hygiene, the research conducted by Mjøen manifested a racialised understanding of the Sámi. Comparative anthropological measures of height, head circumference, eye and hair colour, seemingly confirmed in the view of the scientists the hypothesis that the indigenous people were underdeveloped. Their inferiority was considered a threat to the development of the Norwegian population, and so-called race crossings were seen as ‘unharmonic’ [sic] and officially advised against. Norway has come a long way since racial hygiene was a mainstream scientific approach. Modern genetics have powerfully refuted the hypothesis of distinct racial categories of human beings.

Yet, the racialised understanding lingers, as the utterances by the convicted man in the Salten case show. His comment on Facebook included this statement:

Who trusts the Sami? No one, [there’s] not one honest Sámi. They know what they’re doing, sitting around their lavvo with a hash pipe and thinking about how they should chase out their animals to drain the Norwegian State for kroner.

The man described stereotypical character traits of untrustworthiness (‘Who trusts the Sami? No one, [there’s] not one honest Sámi’), laziness (‘They know what they’re doing, sitting around their lavvo with a hash pipe’), and dishonesty (‘thinking about how they should chase out their animals to drain the Norwegian State for kroner’). He also commented on their body odour (‘smell of lighter fluid’, ‘smell of fire’). He moreover discussed the Sámi phenotype, meaning an individual’s observable traits, such as height, eye colour, and blood type. In discussions of perceived racial differences, phenotypes are commonly misused. Racism and racially motivated crimes build on an understanding of racial differentness, whereby the perpetrator perceives the victim and victim group as inferior based on real or perceived biological characteristics, including phenotypes. Furthermore, the racially different group is understood as inherently (because inherent and unchangeable) inferior.

In his Facebook comment, the man implied that all Sámi are of short body height, stating ‘with his 1.30 meters’. Given the average height of men in Norway of 1.80 meters, this statement indicates yet another element of their ostensible inferiority. He then held that the Sámi do not belong to the ‘civilized’ part of Norway (‘they belong home on the vidda’) or the rest of the world. Rather, he wanted them to go to hell (‘I should have asked them to go to h….’), since he felt so provoked by ‘these Sámi fuckers’ (Norwegian: ‘disse sam jævlan’).

The hateful comments show an understanding of a racial difference between ‘ordinary’ Norwegians and the Sámi. Racism is built on hierarchical understanding of groups, whereby the ‘others’, in our case the Sámi, are considered to have a distinct innate essence. The idea of the Sámi as backward people is very discernible in the Facebook comment: all members of the Sámi people are understood as having the same characteristics and, therefore, as being one. Such perception and group stereotypes remove the individuality of the person. Individuals are relegated to a small, insignificant, and replaceable piece of a larger structure and, thereby, objectified.

Section 185 of the Norwegian Penal Code that regulates hate crime does not explicitly protect members of a racial group. Rather, it refers to ‘skin colour or national or ethnic origin’. The travaux préparatoires of the Penal Code, however, repeatedly refer to ‘racial utterances’ and the obligations of Norway under ICERD, thus implying that racialised utterances are criminalised. The reference to skin colour is deeply problematic because it narrows down racism to differences in pigments, which—traditionally—was one way of categorising people. In days of social Darwinism and race hygiene, skin colour was indeed an indicator of a person’s social hierarchy. However, the case of the Sámi clearly shows that the racial understanding cannot be reduced to differences in pigmentation. Rather, the perception of their racial inferiority, in the view of the convicted individual in the Salten case, is manifested in several different ways. He described their racial otherness in terms of their height, body odours, and, in his view, innate characteristics, which ostensibly all Sámi share.

Reducing hate speech to that based on a person’s skin colour, excludes strictu sensu cases of racialised hate speech based on a person’s hair, body complexity, nose shape, ear size, etc. History provides us with an abundance of examples where race was not defined by means of a person’s different skin colour. Of course, the Sámi are also protected against hate speech based on their ethnicity, however, most of the comments of the convicted man in the Salten case were not based on ethnicity, but an ingrained understanding of racial otherness. As such, it would be advisable to revise section 185 by removing references to ‘skin colour’ and including ‘race’ as a category alongside national and ethnic origin. In mainstream science, race is understood as a social construct and runs deeper than skin. The concept is broad enough to include any perception of inferiority based on the perpetrator’s understanding of racial characteristics. One body that aims at counteracting hate speech and racism against the Sámi is the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, discussed in the following.

8. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission

The UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous People has stated: ‘Indigenous peoples around the world in the past have suffered gross and systematic violations of their human rights and those violations have ongoing consequences in the present day that continue to affect their human rights situation’. Moreover, without efforts of meaningful reconciliation, it is difficult for indigenous peoples to overcome their extreme marginalisation and to ensure sustainable relationships built on trust, respect, and partnership between them and their home State.

The Norwegian Parliament appointed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2018. Its mandate is to investigate injustices committed against Sámi, Kvens, and forest Finns as a result of the Norwegianisation policy. One explicit aim of the Commission is the investigation into the ‘aftermath of the Norwegianisation policy in today’s society, for example in the form of hate speech and discrimination’. The explicit focus on hate speech and discrimination indicates a recognition of their (wide) remit and will likely have consequences for the political, economic, social, and judicial treatment of such cases. The Commission plans to submit its proposals for actions that can contribute to further reconciliation by 1 June 2023.

A report with proposals alone is, however, not sufficient. For a complete reconciliation, the indigenous peoples must also be provided the full enjoyment of their rights, including the freedom from discrimination. The Sámi discrimination has, as discussed above, its roots in a perceived superiority of the majority population. These perceptions were historically accompanied by laws and policies, in Norway and elsewhere, with an aim at suppressing, eliminating, and/or assimilating the indigenous identity. The laws on schooling and on the use of land had the largest impact. The law on grazing of the reindeer (reinbeiteloven) and the felleslappeloven that gave agriculture priority over reindeer husbandry were, for instance, exclusively administrated by non-Sámi, entailing an interpretation favourable to the Norwegian agriculturalists. A full reconciliation would necessitate not only the recognition of past wrongs, but also a redistribution of land and resource rights, and a revamping of legislation and jurisprudence that takes into account the Sámi history in Norway, their living conditions, education, socioeconomic status, health, and more. The Sámi legal traditions and their (unwritten) customary laws have to be fully recognised by the Norwegian courts and administration as a source of the same legal value as other Norwegian laws and regulations. In practical terms, such recognition could potentially entail the setting aside of statutory laws in favour of (unwritten) Sámi customary laws.

The UN Special Rapporteur recognises that ‘there is a strong legal and policy foundation upon which to move forward with the implementation of indigenous peoples’ rights’, but also notes that numerous obstacles prevent the indigenous peoples from full enjoyment of their human rights, ‘found to some extent in all countries where indigenous people are living’. The law and its full implementation on behalf of the Sámi is therefore one of the main pillars of the reconciliation.

9. The (possible) ways forward

The examples of grave denigration show that the Sámi historically and still today suffer from hate speech in the public arena based on ostensible racial characteristics. It would therefore be wrong to remove section 185 of the Norwegian Penal Act, as certain commentators have suggested. On the contrary, a discussion with a view to including the hate speech committed with a racial bias ought to be re-invigorated. Making racialised crimes punishable corresponds to the aims of ICERD. The racism that the Sámi experience is very real and will not be lessened unless it is recognised, acknowledged, and they are given redress for these rights violations. Norway as State Party to numerous legal instruments that protect minorities and/or indigenous peoples has a legal obligation to ensure the fulfilment of their rights and freedoms. This includes the acknowledgment of a narrower margin of appreciation of the State of Norway in the adjudication of human rights violations constituted by discrimination and hate speech directed at the historically marginalised Sámi.

In addition to focusing on increasing investigations, prosecutions, and conviction for hate crimes against the Sámi, another issue should be addressed: by increasing the recruitment of State officials with Sámi background—or any other minority for the sake of the argument—the State would achieve greater parity, which would be beneficial to all. A more balanced staffing of police officers, public prosecutors, and judges would ensure that the historical wrongdoing is set into a proper context when hate crimes are adjudicated. A more even distribution would increase trust in the system and, hopefully, more victims would report crimes committed against them.

Education on the treatment of the Norwegian minorities is crucial, be it in the form of courses for present and future (State) employees or in the school curriculum for children and youth. The history of social Darwinism, racial hygiene, and the assimilation policy resonate in the present hate discourse that is directed against the Sámi. It is important that the State unambiguously asserts that it is neither socially, politically, nor legally permissible. The Salten judgment and its successor cases are, in this respect, an important step in the right direction. In their judgments, the courts very clearly recognised the grave denigration of the Sámi and sentenced the accused for his degrading and undignified comments in a public forum. The judgments, however, must be disseminated and followed up. Increased (legal and other) research on the Sámi can contribute with knowledge and alter perceptions and (mis)understandings. In particular, there must be a foregrounding of research by Sámi scholars as well as research that takes indigenous perspectives into consideration. Of course, any solution ought to be considered also in the light of the ongoing debate over improving the Sámi’s right to internal self-determination, including extension of the authority of the Sámi regional parliament. That, however, is a topic for another article.

- 1TSALT-2018-159702 (1 February 2019) Salten tingrett 6-7 (‘Retten finner flere av tiltaltes utsagn svært nedlatende, nedverdigende og krenkende overfor samer generelt’, and ‘Etter rettens syn er tiltaltes ytringer samlet sett kvalifisert krenkende og innebærer en grov nedvurdering av samer’).

- 2Johan Ante Utsi, Anders Boine Verstad, ‘Mann dømt for hatefulle ytringer: Han kalte dette for klovnedrakt’ NRK Sámpi (24 May 2019) <www.nrk.no/sapmi/mann-domt-for-hatefulle-ytringer_-_-han-kalte-dette-for-klovnedrakt-1.14563099>; Johan Ante Utsi, Mariela Idivuoma, ‘Vitne: Denne saken er den verste samehetsen jeg har opplevd’ NRK Sámpi (15 May 2019) <www.nrk.no/sapmi/_-denne-saken-er-den-verste-samehetsen-jeg-har-opplevd-1.14551429>. All websites last accessed 25 July 2021. All translations by the author.

- 3LH-2019-036965 (24 May 2019) Hålogaland lagmannsrett.

- 4TSALT-2018-159702 (n 1).

- 5Cf Rauna Kuokkanen, ‘Reconciliation as a Threat or Structural Change? The Truth and Reconciliation Process and Settler Colonial Policy Making in Finland’ (2020) 21 Human Rights Review 293, 294 (noting that ‘there is very little public knowledge and awareness about the Sámi, and their society, colonial history, culture or rights in the Nordic countries’).

- 6International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), ‘Indigenous Peoples in Sápmi’, <https://www.iwgia.org/en/sapmi/4248-iw-2021-sapmi.html>; Regjeringen, Meld St 31 (2018-2019) Samisk språk, kultur og samfunnsliv nr 2.1; Arnfinn Midtbøen and Hilde Lindén, ‘Kumulativ diskriminering’ (2016) 1 Sosiologisk tidsskrift 3, 15, 17. Estimated registered Sámi in 2005: Norway 57,567; Sweden 20,000; Finland 7500; Russia 2000. See Astri Andresen, Bjørg Evjen, and Teemu Ryymin (eds), Samenes Historie: fra 1751 til 2010 (Cappelen Damm Akademisk 2021) 49.

- 7Sametinget, ‘Sametingets valgmanntall’, <https://sametinget.no/politikk/valg/sametingets-valgmanntall/sametingets-valgmanntall-2009-2019/>.

- 8Astrid Eriksen, Breaking the Silence – Interpersonal Violence and Health among Sami and non-Sami: A Population-based Study in Mid-and Northern Norway (PhD thesis, University of Tromsø 2017) 44.

- 9Russia and Finland did not implement a targeted assimilation policy of the Sámi, while Sweden combined assimilation with segregation: see further Andresen and others (n 6) 179-181.

- 10Note that modern indigenous historiographies and methodologies reject the traditional portrayal of indigenous peoples as exclusively victims: see further Andresen and others (n 6) 22-23.

- 11Paul Taylor, Race: A Philosophical Introduction (2nd ed, Polity 2013) 42; Jon Røyne Kyllingstad, Kortskaller og Langskaller: Fysisk Antropologi i Norge og Striden om det Nordiske Herremennesket (Scandinavian Academic Press 2004) 17; Michael Banton, Racial Theories (2nd ed, Cambridge University Press 1998) 84-86.

- 12Robert Wald Sussman, The Myth of Race: The Troubling Persistence of an Unscientific Idea (Harvard University Press 2014) 48.

- 13Wolfgang Bialas, ‘The Eternal Violence of the Blood: Racial Science and Nazi Ethics’ in Anton Weiss-Wendt and Rory Yeomans (eds), Racial Science in Hitler’s New Europe, 1938-1945 (University of Nebraska Press 2013) 358; Andresen and others (n 6) 136.

- 14Amy Carney, ‘Preserving the ‘Master Race’’ in Anton Weiss-Wendt, Rory Yeomans (eds), Racial Science in Hitler’s New Europe (University of Nebraska Press 2013) 62; Kyllingstad (n 11) 80; Andresen and others (n 6) 16.

- 15Andresen and others (n 6) 16-17.

- 16Kyllingstad (n 11) 160-61; Jon Røyne Kyllingstad, Measuring the Master Race: Physical Anthropology in Norway 1890-1945 (Open Book Publishers 2014) 100-2; Eva Maria Fjellheim, ‘Through Our Stories We Resist: Decolonial Perspectives on South Saami History, Indigeneity and Rights’ in Anders Breidlid and Roy Krøvel (eds), Indigenous Knowledges and the Sustainable Development Agenda (Routledge 2020) 207, 212.

- 17Note that already in the 1880s, the authorities were aware that ‘lapp’ was a degrading term and that ‘sam’ was the term that the Sámi used themselves: Andresen and others (n 6) 70.

- 18Kyllingstad (n 11) 81; Andresen and others (n 6) 25.

- 19Kyllingstad (n 11) 57; Kyllingstad (n 16) 84. Confirmed by Andresen and others (n 6) 133, 137, 143.

- 20Kyllingstad (n 11) 57.

- 21Quoted in Lars Beckman, Ras och Rasfördomar (Prisma 1966) 60.

- 22Quoted in Kyllingstad (n 11) 110. Confirmed by Andresen and others (n 6) 47, 62.

- 23Andresen and others (n 6) 46-47, 129-32, 154-55.

- 24ibid, 17-18.

- 25Kirsti Bull Strøm, ‘Urfolksrettigheter’ in Andreas Føllesdal, Morten Ruud, and Geir Ulfstein (eds) Menneskerettighetene og Norge: Rettsutvikling, rettsliggjøring og demokrati (Universitetsforlaget 2017) 298, 301; Andresen and others (n 6) 17, 51; Henry Minde, ‘Fornorskinga av Samene – hvorfor, hvordan og hvilke følger? (2005) 3 Gáldu Čála: Tidsskrift for urfolks rettigheter 5, 11.

- 26Andresen and others (n 6) 136-37; Minde (n 25) 7, 11.

- 27Sigmund Elgarøy and Petter Aaslestad, ‘“… det er ingen rede at faa paa ham”: Samiske pasienters psykiatrijournaler 1902–1940’ (2010) Psykolog Tidsskriftet, <https://psykologtidsskriftet.no/fagartikkel/2010/07/det-er-ingen-rede-faa-paa-ham-samiske-pasienters-psykiatrijournaler-1902-1940>.

- 28Elgarøy and Aaslestad (n 27).

- 29Minde (n 25) 5; Andresen and others (n 6) 157-217.

- 30NOU 2016:18, Hjertespråket — Forslag til lovverk, tiltak og ordninger for samiske språk section 4.2.4.

- 31ibid. See also Fjellheim (n 16) 208, 212; Minde (n 25) 6, 12.

- 32Andresen and others (n 6) 146.

- 33NOU 2016:18 (n 30) Section 4.2.2; Minde (n 25) 9; Andresen and others (n 6) 165, 168-69.

- 34Minde (n 25) 5.

- 35Andresen and others (n 6) 168-69, 182.

- 36Andresen and others (n 6) 174-75, 329-32; Minde (n 25) 13-17.

- 37Minde (n 25) 12, 17.

- 38Section 108 was incorporated into the Constitution in 1988 (then as Section 110A). It establishes the minimum legal, political, and moral standard for Norwegian authorities’ obligations toward the Sámi.

- 39Lov om Sametinget og andre samiske rettsforhold (sameloven) §§ 3-1 – 3-12.

- 40Lov om grunnskolen og den vidaregåande opplæringa (opplæringslova) §§ 6-1 – 6-4.

- 41Government of Norway, Facts about the Sámi languages (2018), <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/urfolk-og-minoriteter/samepolitikk/samiske-sprak/fakta-om-samiske-sprak/id633131/>.

- 42Asbjørn Eide, ‘United Nations Standard-Setting regarding Rights of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples’ (2014) 71(3-4) Europa Ethnica 51, 57-58 <https://doi.org/10.24989/0014-2492-2014-34-51>; Stefan Oeter, ‘The Protection of Indigenous Peoples in International Law Revisited: From Non-Discrimination to Self-Determination’ in Holger Hestermeyer and others (eds), Coexistence, Cooperation and Solidarity: Liber Amicorum Rüdiger Wolfrum (Martinus Nijhoff 2012) 477, 482.

- 43Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, International Standards, <https://www.ohchr.org/en/issues/minorities/srminorities/pages/standards.aspx>.

- 44HR-2021-1975-S (11 October 2021) para 101. See also: HR-2017-2428-A (21 December 2017) paras 54-55.

- 45Alexandra Xanthaki, ‘International instruments on Cultural Heritage: Tales of Fragmentation’ in Alexandra Xanthaiki and others (eds), Indigenous Peoples’ Cultural Heritage: Rights, Debates and Challenges (Brill Nijhoff 2017) 1, 11; Matthias Åhrén, Indigenous Peoples’ Status in the International Legal System (Oxford University Press 2016) 105.

- 46Lubicon Lake Band v Canada, CCPR-1984-167 (26 March 1990); Oeter (n 42) 480; Åhrén (n 45) 90-93.

- 47Lov om straff (straffeloven) 20 mai 2005 nr 28.

- 48UN Human Rights Committee, Concluding Observations on the Seventh Periodic Report of Norway, UN Doc CCPR/C/NOR/CO/7 (25 April 2018) para 16.

- 49ibid, para 17.

- 50Entry into force 21 May 1999.

- 51Council of Europe, About the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, <https://www.coe.int/en/web/minorities/at-a-glance>.

- 52Midtbøen and Lidén (n 6) 12.

- 53ibid 13.

- 54Oeter (n 42) 482; Åhrén (n 45) 95.

- 55Oeter (n 42) 485.

- 56ibid 498.

- 57ibid 492, 496-7; Åhrén (n 45) 101-5.

- 58UNESCO, ‘How to ratify the 2003 Convention?’, <https://ich.unesco.org/en/how-to-ratify-00023>.

- 59UNESCO, ‘Dive into intangible cultural heritage!’, <https://ich.unesco.org/en/dive&display=threat>.

- 60Fjellheim (n 16) 213, 221.

- 61Stereotypes are beliefs and opinions about the characteristics, attributes, and behaviours of members of certain groups. Prejudice is an attitude directed toward people because they are members of a specific social group. See further Bernard Whitley and Mary Kite, The Psychology of Prejudice and Discrimination (2nd ed, Routledge 2010) 11.

- 62LH-2019-036965 (n 3) 7 (‘Ytringene er samlet sett kvalifisert krenkende og innebærer en grov nedvurdering av samer som etnisk minoritet’).

- 63Rebecca Cook and Simone Cusack, Gender Stereotyping: Transnational Legal Perspectives (University of Pennsylvania Press 2010) 41.

- 64Erving Goffman, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (Simon & Schuster 969) 3.

- 65Eg Article 19 ICCPR and Article 10 of the European Convention on the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR).

- 66For a discussion on recent case law, see Iris Nguyên Duy, ‘The Limits to Free Speech on Social Media: On Two Recent Decisions of the Supreme Court of Norway’ (2020) 38 Nordic Journal of Human Rights 237, 237-45 <https://doi.org/10.1080/18918131.2021.1872762>.

- 67Andreas Motzfeldt Kravik, ‘Rasismeparagrafen bør bevares’ Minerva (4 March 2013) <https://www.minervanett.no/rasismeparagrafen-bor-bevares/139231>.

- 68Article 4(a) of the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, ICERD.

- 69Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Opinion under Article 14 ICERD, Communication No 30/2003, UN Doc CERD/C/67/D/30/2003 (22 August 2005) para 10.5 on the Supreme Court of Norway’s decision in the case of Sjølie (Rt 2002, s 1618).

- 70Alajos Kiss v Hungary, no 38832/06, § 42, ECHR 2010.

- 71The Norwegian Supreme Court has held that legal interpretations of the ICCPR by the UN Human Rights Committee have considerable weight as a source of law: HR-2017-2428-A (21 December 2017) § 57.

- 72Supreme Court decisions: HR-2020-2133-A; HR-2020-184-A; HR-2020-185-A; HR-2018-674-A; HR-2012-689-A; HR-2007-02150-A; HR-2001-01428.

- 73Concluding Observations (n 48) paras 16, 17(d).

- 74Johan Ante Utsi and Biret Ravdna Eira, ‘Har anmeldt samehets 20 ganger’ NRK Sámpi (28 January 2018) <https://www.nrk.no/sapmi/hans-petersen-anmeldte-samehets-20-ganger-for-saken-ble-tatt-opp-i-retten-1.14398182>.

- 75Mette Ballovara, ‘Mann bøtelagt for hatefulle ytringer – Hanne tror dette kan bremse samehets’ NRK Sámpi (6 May 2020) <https://www.nrk.no/sapmi/mann-botelagt-for-hatefulle-ytringer-_-hanne-tror-dette-kan-bremse-samehets-1.15005758>.

- 76Anders Boine Verstad and Lena Marja Myrskog, ‘Anmeldte netthets: – Noe av det verste jeg har lest’ NRK Sámpi (27 May 2021) <https://www.nrk.no/sapmi/sametingsrepresentant-runar-myrnes-balto-anmeldte-netthets-mot-samer-1.15511070>. As per 15 October 2021, the judgment is not publicly available.

- 77TSALT-2018-159702 (n 1).

- 78LH-2019-036965 (n 3).

- 79Supreme Court decisions: HR-2020-2133-A (5 May 2020) para 23; HR-2020-184-A (29 January 2020) para 27; HR-2020-185-A (29 January 2020) para 19; HR-2018-674-A (12 April 2018) para 20; HR-2012-689-A (30 March 2012) para 26; HR-2007-02150-A (21 December 2007) para 32.

- 80Midtbøen and Lindén (n 6) 9-10, 18.

- 81ibid 20.

- 82Eriksen (n 8) 47-50; NIM, Vold og overgrep i samiske samfunn (2018) 28, <https://www.nhri.no/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/NNIM_temarapport_web.pdf>. Notably, the report does not differentiate regarding the perpetrator’s ethnic background.

- 83Eriksen (n 8) 20.

- 84Rune Andreassen, ‘Utsatt for vold på bryllupsfest: – han sa at han hadde lyst til å slå en same’ NRK (21 September 2019) <https://www.nrk.no/tromsogfinnmark/utsatt-for-vold-pa-bryllupsfest_-__han-sa-at-han-hadde-lyst-til-a-sla-en-same-1.14712526>.Inga Kare Marja Utsi, Emmi Alette Danielsen, and Johan Ante Utsi, ‘Samehets-sak ble henlagt – unge vil ha tiltak mot hatkriminalitet’ NRK (11 December 2020) <https://www.nrk.no/sapmi/unge-vil-ha-tiltak-mot-samehets-etter-flere-episoder-i-tromso-1.15282662>.

- 85Lena Marja Myrskog and Marit Sofie Holmestrand, ‘Protestaksjoner mot samevold: – Bysamen er kommet for å bli’ NRK (28 September 2019) <https://www.nrk.no/sapmi/markeringer-mot-samevold_-_-bysamen-er-kommet-for-a-bli-1.14721752>.

- 86Quoted in Markus Thonhaugen and Andreas Budalen, ‘NRK-profil reagerer på å bli brukt som eksempel i rettssak om samehets’ NRK (22 January 2019) <https://www.nrk.no/nordland/nrk-profil-reagerer-pa-a-bli-brukt-som-eksempel-i-rettssak-om-samehets-1.14393449>.

- 87Concluding Observations (n 48) para 37(a).

- 88Berit Solveig Gaup and Mette Ballovara, ‘Raja er rystet over samehets i Tromsø’ NRK (7 December 2020) <https://www.nrk.no/sapmi/kulturministeren-er-rystet-over-samehets-i-tromso-1.15277285>.

- 89Joik (or yoik) is the traditional form of song in Sámi music.

- 90Marita Andersen and others, ‘Opprop mot samehets i Tromsø tar av på sosiale medier’ NRK (9 December 2020) <https://www.nrk.no/tromsogfinnmark/opprop-mot-samehets-i-tromso-tar-av-pa-sosiale-medier-1.15280873>.

- 91Ginevra Le Moli, ‘The Principle of Human Dignity in International Law’ in Mads Andenæs and others (eds), General Principles and the Coherence of International Law (Brill 2019) 352.

- 92Marita Melhus and Ann Ragnhild Broderstad, Folkehelseundersøkelsen i Troms og Finnmark, Tilleggsrapport om samisk og kvensk/ norskfinsk befolkning (2020) <https://fido.nrk.no/a638cb7368b1ee2631e368cf24b8c9023bd15439e595e90697f07b43cf369a4e/Rapport_Troms_Finnmark_SSHF_redigert_april2020.pdf>.

- 93Regjeringen, Justis- og beredskapsdepartement, ‘Statsbudsjettet 2021: Vi må bekjempe hatkriminalitet’ (7 October 2020) <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/–vi-ma-bekjempe-hatkriminalitet/id2768815/>. The budget was approved on 1 December 2020.

- 94ibid.

- 95European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, Hate Crime in the European Union (undated), <https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra-factsheet_hatecrime_en_final_0.pdf>. On the EU level, the Roma are overrepresented as victims of hate crimes. Norway is not a member of the EU and was not included in the survey.

- 96Beizaras and Levickas v Lithuania, no 41288/15, § 155, ECHR 2020.

- 97Identoba and Others v Georgia, no 73235/12, § 77, ECHR 2015.

- 98European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (n 95).

- 99ibid.

- 100Concluding Observations (n 48), para 17c.

- 101Michael Banton, What We Now Know About Race and Ethnicity (Berghahn 2015) 92.

- 102Taylor (n 11) 48-51; Kazuko Suzuki and Diego von Vacano, ‘A Critical Analysis of Racial Categories in the Age of Genomics’ in Kazuko Suzuki and Diego von Vacano (eds), Reconsidering Race: Social Science Perspectives on Racial Categories in the Age of Genomics (Oxford University Press 2018) 1-17.

- 103Carola Lingaas, The Concept of Race in International Criminal Law (Routledge 2019) 40-45.

- 104Andrea Rodriguez-Martinez and others, ‘Height and Body-Mass Index Trajectories of School-Aged Children and Adolescents from 1985 to 2019 in 200 Countries and Territories: a Pooled Analysis of 2181 Population-Based Studies with 65 Million Participants’ (2020) 396 The Lancet 1511, 1511–24 <https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31859-6>.

- 105Ot prp nr 8 (2007-2008) 247-51.

- 106For an in-depth analysis of race and its legal definition, see Lingaas (n 103).

- 107ibid 35, 92, 175, 232.

- 108Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Victoria Tauli Corpuz, UN Doc A/HRC/27/52 (11 August 2014) para 27.

- 109ibid.

- 110Truth and Reconciliation Commission, <https://uit.no/kommisjonen/mandat>.

- 111Truth and Reconciliation Commission, <https://uit.no/kommisjonen/presse/artikkel?p_document_id=735000>.

- 112Report of the Special Rapporteur (n 108) paras 34-5.

- 113Andresen and others (n 6) 195-96.

- 114Kuokkanen (n 5) 304.

- 115Report of the Special Rapporteur (n 108), paras 57-8.

- 116Carl Müller Frøland, ‘Derfor bør vi ikke beholde “rasismeparagrafen”’ Khrono (8 August 2020) <https://khrono.no/derfor-bor-vi-ikke-beholde-rasismeparagrafen/505955>.

- 117Fjellheim (n 16) 207-9, 215-20.